|

Interviewer:

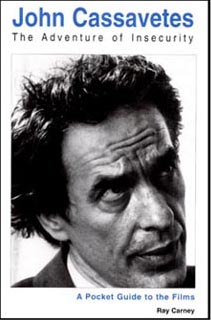

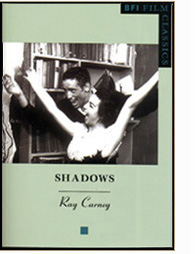

Can you summarize what you were doing in your two most recent books –

the Cassavetes on Cassavetes and the book on Shadows? Interviewer:

Can you summarize what you were doing in your two most recent books –

the Cassavetes on Cassavetes and the book on Shadows?

Carney: What I was doing?

Interviewer: Why did you

write them?

Carney: For a lot of different

reasons – most of which I didn't understand until years into the process.

Consciousness is always the last to know. Only in the struggle to express

and structure something do you discover what you want to say. You can't

know what you are doing until you do it. Like talking. You learn what

you think in the process of saying it. That's the way it's been with everything

I've ever written.

Interviewer: Is that frustrating

or confusing?

Carney: No, it's actually a

pretty neat thing. It keeps a project interesting because you keep changing

your mind and understanding it differently as you go along. In fact I

tell filmmakers who write me that if the film they end up with is the

same one they thought they were going to be making when they started,

or if they feel the same way about the characters as they did when they

wrote the script, they have wasted their time.

Interviewer: Why is that?

Carney: Because they haven't

allowed themselves to learn anything. As Nick Ray said, if it's all in

the script why bother to make the movie? Publish the script. That's a

lot cheaper and quicker.

Interviewer:

Can you describe what you learned as you wrote the Cassavetes on Cassavetes

book? Interviewer:

Can you describe what you learned as you wrote the Cassavetes on Cassavetes

book?

Carney: I guess I started out

thinking it would be a much simpler study than it turned out to be – pretty

much a straightforward biography – one that focused on the events connected

with the making of the films than on the personal life. The structure

would be to alternate explanatory factual paragraphs – my words – with Cassavetes'

statements – his words. But it turned into an deep examination of Cassavetes'

soul. And even the simplest facts took heroic efforts to ferret out.

Interviewer: What do you

mean?

Carney: The amount of research

required to establish even the most basic facts was staggering. Since

I was writing the first biography, there was no previous biography to

consult; and to make things worse, the facts were hopelessly confused

in all of the standard reference books. You could find five or six conflicting

versions of even the simplest events – like the year Rowlands was born,

or when she married Cassavetes, or where Cassavetes went to college, or

the date a particular film was made or released.

As I did the basic research

I found out that all of the reference books were wrong. So I really

had to begin from square one. I realized I couldn't trust anything that

had been published. I had to check every individual fact. It took me years

to sort out the myths and work down to the realities.

Interviewer: Why were there

so many mistaken accounts?

Carney: Cassavetes and Rowlands

simply made a lot of it up. They both had a high sense of privacy, and

not a lot of respect for reporters. One of Cassavetes' bits of advice

to friends used to be: “Just remember you don't owe reporters the

truth.” So he and Rowlands would tell journalists whatever they wanted

to hear. And since all the reference books are based on newspaper reports

and press releases, they are full of errors.

You know the way these books

are written, don't you? No one actually does any research.

Interviewer: What do you

mean? Interviewer: What do you

mean?

Carney: The way most reference

books are put together is that the editor or author of an entry simply

goes to two or three earlier reference books and re-writes what they say

and inserts it in his book. No one actually checks any of the facts.

One reference book borrows from another and a third quotes or borrows

from the second in an endless, fictional ring-a-round-the-rosy of mistakes

which are repeated in book after book. It's like a bad student paper.

“Research” consists of copying the article out of another book,

lightly rewritten to avoid charges of plagiarism. If a student did this,

he'd be thrown out of school; but when the Encyclopedia Britannica

does it, it's apparently OK.

The result is that once someone

publishes a screwed up account of something in Cassavetes' life – say,

that he majored in English at Colgate, or that he took the money he made

from his Johnny Staccato television series and went off to make

Shadows with it, or that Faces was filmed in 1968, or that

his work was improvised – then everyone else reprints it and the mistakes

assume the status of facts – since all the books say they are

true!

The American Film Institute

web site still misspells Cassavetes' name in some of its entries.

The PBS American Masters internet listing has him attending colleges

he never went to, gives wrong dates and facts about the filming of Shadows

and Faces, and misspells Gena Rowlands' name. The 2002 edition

of the Encyclopedia Britannica has Cassavetes attending the wrong

college, majoring in something he never studied, has the wrong movie for

his first film acting appearance, the wrong show for his television debut,

and the wrong date for the release of Shadows. (Click here to see the Google display of web sites, including those for The Encyclopedia Britannica, Time Magazine, Encarta, The New York Times, and PBS's American Masters television biography series that still show Cassavetes to be a Colgate graduate, even at this late date two decades after his death.)

That's a fair indication of

the reliability of the English-language reference books. The French are

worse; they make us look good. Cassavetes is kind of a cult figure there

and it's one of the curses of something being popular that since you can

sell more or less anything that is published on the subject, there is

no pressure to do good work. It's like Microsoft and software. If you're

too successful, there's no incentive to do it right. There are four or

five books about Cassavetes in French and every one of them is riddled

with hilarious errors. The worst of the lot is one by a woman named Nicole

Brenez. It is like reading science fiction – if you know anything about

Cassavetes. Among American critics, Jonathan Rosenbaum has perpetuated

many of these errors in his writing. It turns out he and Brenez are friends.

He should pick his friends more carefully – or be more careful about praising

their work.

Interviewer: It's a little

surprising to learn that you were the first person to check any of the

facts. Cassavetes has been dead twelve years.

Carney: It tells you something

about the critical neglect of his work and the shabbiness of what passes

for film scholarship – in Chicago and Paris. Research takes a lot of time

and energy. You can't just do a flyby. Rosenbaum's work is pretty shabby,

but he isn't alone. The documentary films that have been done about Cassavetes

are just as full of mistakes. They were all quickie jobs – you know, you

fly into New York or Los Angeles for five days, grab interviews with everyone

you can get, and edit the whole thing in a rush to beat some film festival

or broadcast deadline.

Interviewer:

How did you arrive at the truth? Interviewer:

How did you arrive at the truth?

Carney: There's no shortcut.

I went to the sources. I wrote hospitals to get birth dates. I checked

theater logs to get release dates. I scrolled through miles of microfilm

in library basements reading fifty year old newspapers. It took years – and

thousands of hours.

It was a slow process. And

a hard one. Some of the facts came from talking with people who had worked

with Cassavetes – Peter Falk or Ben Gazzara or Bo Harwood or someone else.

But people's memories are very fallible and incomplete and untrustworthy

and most of the important information had to be triangulated.

Interviewer:

Triangulated?

Carney: You know, the way the

CIA works! You piece an event together from someone's memory, combined

with a sentence in a press release, combined with a mention of something

in a newspaper article, combined with something Cassavetes himself said

that related to the issue – hours or days of research – which would, when

I put all of the information together, result in a single sentence in

a headnote.

It might take something like

a dozen hours of research to write the section of the book where I talk

about how Cassavetes' drafted three scripts of the play version of A

Woman Under the Influence in a certain month; revised them in another;

persuaded Ben Gazzara to appear in the play; went out to Wisconsin to

raise money; failed; went to New York to attempt to persuade Joe Papp

to mount it; failed again; combined the scripts into one film script;

showed the revision to Peter Falk during a meeting with Elaine May about

Mikey and Nicky, and so on. There was no one person who knew the

whole story except for Cassavetes himself and he had died by the point

that I wanted the details. So you piece it all together from the individual

parts that Ben and Peter and Gena knew. A very labor intensive method.

I watch the crawls on Nova and Frontline where the names

of the researchers are listed with a little more reverence nowadays! And

since I had no money to do any of it, my students and I did a lot of it

late at night after our classes or day jobs were over. The internet by

the way was of almost no use. Surprise. You have to take a trip to the

library. We did our research the old fashioned way.

Interviewer: Can you talk

about the long table you showed me before we began? Interviewer: Can you talk

about the long table you showed me before we began?

Carney: Sure. I call it “the

bible.” I began by creating a massive timeline in database form with

fields for every month of Cassavetes' life. Then I and my student volunteers

went about filling it in, block by block. Since there were so many myths

in circulation, getting at the truth was a Rashomon-like process

of consulting all available sources of information and piecing together

the most likely version of what really happened, based on where the various

accounts agreed, working from the known to the unknown, one fact at a

time.

We began by filling in every

documented event that could be pinned down – like the date a certain film

was released in a particular city or the date and place Cassavetes gave

a particular interview. A lot of that was information that could be obtained

from a newspaper, radio, or television station librarian. Then I picked

the brains of people who knew Cassavetes at various times in his life

and who had lived through particular events. I read all of the published

interviews any of them had ever given; obtained tapes or transcripts of

unpublished interviews with them; and conducted hundreds of hours of additional

interviews on the phone, by email, or in person.

Since I knew most of these

people and they were enthusiastic about the project, almost all of them

were extremely helpful. Beyond sharing their recollections, a number of

them – Ted Allan, Sam Shaw, Meta Shaw, Edie Shaw, Larry Shaw, Susan Shaw,

Bo Harwood, Mike Ferris, George O'Halloran, Hugh Hurd, Lelia Goldoni,

and Mo McEndree most notably – provided treasure troves of private material:

story-boards that Cassavetes used during his editing process, layouts

for posters and ad campaigns with his comments on them, unpublished interviews,

drafts of scripts, press clippings – amazing unknown material. Sam Shaw

spent odd moments writing out his recollections and sending them to me

for more than five years.

The fact-checking went on for

years. I would learn something new from one person or source and then

check it out with everyone else who might have information about it. Meanwhile,

I assembled a clipping file based on published newspaper and magazine

accounts which I used to cross-check peoples' memories of dates and events.

I have three file cabinets bulging with clippings. The final strand of

the weave was piles of material that were sitting more or less untouched

in film archives.

I can't begin to communicate

how challenging it was to establish even basic sequences of events. Myths,

misconceptions, and press release versions of reality were everywhere.

I checked everything I possibly could six ways to Sunday, but I'm sure

a few mistakes sneaked into the book despite my best efforts to ferret

them out. That's why it took almost eleven years to do it. In the case

of the conversations I had with individuals, I worked with a degree of

urgency since I knew that they wouldn't be around forever. I was really

lucky to have had a chance to talk to some of them while they were still

around. Ted Allan, Sam Shaw, and Hugh Hurd have all died since I began

my research. Fortunately I spent hours with each of them.

Interviewer: Sounds like

a lot of work.

Carney: There is a lot of information

in the headnotes. If you took them out of the book and simply printed

them one after another, you'd have a book-length biography. I actually

did that at one point, printed out all the headnotes separately, so I

could read them as one continuous narrative. And they made a book by themselves.

In effect, I was researching and writing the first biography ever written

about Cassavetes. It's hard to quantify, but my best guess would be that

there are at least five thousand new facts and events in the headnotes

that have never appeared in print before. And that was just the headnotes.

Interviewer: What do you

mean? Interviewer: What do you

mean?

Carney: Well, the Cassavetes

on Cassavetes book consists of two parallel texts – my words and

Cassavetes' words. My words were only part of it. For his words, I could

draw from my own interactions with him in the final decade of his life – letters,

phone calls, and conversations – but I wanted the book to represent

his thoughts at different stages of his career, so I contacted universities,

film archives, radio and television stations, and newspapers all over

the country – everywhere that I could imagine he had ever given an

interview or appeared at an event – to dredge up statements he had

made. Since newspapers and magazines so heavily edit anything they print,

wherever possible I located the actual audiotape or raw transcript, rather

than relying on the published transcription.

The problem

then was that I had far too much to use. Even early in the process I accumulated

more material than I could ever put in a single book. So I knew I would

have to leave a lot out. Every single paragraph quoting Cassavetes' thoughts

about a subject involved comparing five or ten different statements he

made dealing with that particular topic, and selecting the best or most

revealing answers – often by weaving together sentences from different

statements. I explain the rationale in the Introduction.

The combined text then went

through various drafts as I showed it to friends. A few years into the

process, I learned that it was such a hot commodity that it was being

pirated. Fuzzy, dog-eared Xeroxes of Xeroxes of Xeroxes were being passed

from hand to hand by young actors in New York.

Interviewer: How did you

find that out?

Carney: I think the first time

was when I was on a radio talk show to promote another book. I was out

in the hall, chatting with Louis Malle and Brooke Smith who had been on

before me. It may have been to talk about Vanya on 42nd Street.

I made some reference to Cassavetes, and Brooke told me she had this manuscript

that she kept on her night table. She told me how amazing it was and that

if I was interested in Cassavetes I should read it! Of course, I instantly

realized she was talking about one of the early drafts of my own book!

We had a good laugh over that. Her Xerox was so removed from the original

that there was no acknowledgement that I had compiled it.

There were a number of other

encounters like that over the years. When Jim McKay interviewed me for

Filmmaker magazine he told me a similar story of how he had a pirated

typescript which he read for encouragement and inspiration.

Interviewer:

Were you angry about being pirated? Interviewer:

Were you angry about being pirated?

Carney: No. I felt terrific.

Don't forget we're talking about a point at which I couldn't pay

anybody to publish the book. I would have personally presented a copy

to every actor in New York just to know that it was getting read by somebody.

There are lots of good books, going way back to Shakespeare's Sonnets

and many of his plays, that have circulated in pirated copies long before

anyone saw fit to print them.

Interviewer: So it took

you almost ten years to put the quotes together and work out all the facts,

before you were done?

Carney: Not at all. Not even

close. That was just the beginning. The really fun, really hard part remained.

Getting quotes and determining facts was only a small part of the process – and

not really the most important part. The real challenge and fun of writing

the Shadows and Cassavetes on Cassavetes books was the interpretation – deciding

which facts mattered and which didn't; what events should be included

and which should be left out; which issues or aspects of Cassavetes' experience

were related to which others; what causal links existed between different

things; and, above all, what any particular event or fact or quote meant.

Even long after most of the basic facts were established, the meanings

kept changing from day to day, almost from hour to hour.

It made me realize what it

is like to write history – real history, the real way. We get so used to

thinking that the truth is sitting out there waiting for someone to come

along and record it. We have that idea because we are used to looking

things up in a book. But that's a false conception. History – in this case,

the history of Cassavetes' life and work and what it means – isn't just

sitting somewhere waiting to be written down. It's something we create

out of a jumble of this and a mess of that. It's not found; it's made.

And that takes work. A lot of work.

Interviewer: I'm not sure

I follow. Can you say more about what you mean when you say we create

the meaning? When you say we make history? Isn't it just a matter

of establishing the facts? Even if it involves triangulating them, as

you called it before?

Carney: No. Not at all. The

facts are just a step. And not necessarily the first one! You know the

joke about the three umpires for the MIT baseball team? One is a Newtonian.

When batters question his strikes, he responds: “I calls 'em as they

are.” The second knows relativity and replies: “I calls 'em

as I sees 'em.” The third knows quantum mechanics and says: “They

ain't nothing until I call 'em.” Well, when it comes to facts, every

historian has to be a quantum mechanic. There are no facts. There are

only observers. Facts cannot precede an interpretation. The interpretation

creates the fact. Or as Levi-Straus put it, there are no raw data. To

be a datum is to be cooked. Carney: No. Not at all. The

facts are just a step. And not necessarily the first one! You know the

joke about the three umpires for the MIT baseball team? One is a Newtonian.

When batters question his strikes, he responds: “I calls 'em as they

are.” The second knows relativity and replies: “I calls 'em

as I sees 'em.” The third knows quantum mechanics and says: “They

ain't nothing until I call 'em.” Well, when it comes to facts, every

historian has to be a quantum mechanic. There are no facts. There are

only observers. Facts cannot precede an interpretation. The interpretation

creates the fact. Or as Levi-Straus put it, there are no raw data. To

be a datum is to be cooked.

I'm not talking about problems

with differing newspaper accounts or with reference books printing wrong

facts or with people's memories being faulty because something happened

so many years ago. I'm talking about what things mean. I'm talking

about the essential nature of any act of interpretation and understanding

of a lived event. It's not just that people who were first-hand participants

in the exact same events have different feelings and thoughts about the

same things. Its more radical than that. It's that in life events and

facts actually have more than one meaning. There is no simple “meaning”

out there waiting to be exhumed. All lived meanings are much more complex

than that.

I had to function like a novelist

in the Cassavetes on Cassavetes book. That meant at least two different

things: In the first place, it meant sorting out and making allowance

for the biases and perspectival shortcomings and emotional limitations

of the reports I read and the people I talked with. But that was the easy

part. Even more interestingly and complexly, it meant I had to learn how

to decode and make the kinds of meaning that artists make – meanings

that are multiple and unresolved, meanings that contain alternative interpretations

within them, suspended, temporally shifting meanings that are the products

of juxtaposition, comparison and contrast, and are created by context

and sequence. Not dictionary meanings – but dramatic

meanings. The goal was to give the facts and events the complexity of

real experience, and to keep them from falsely becoming clearer or simpler

than the meanings in life are. Writing both books gave me a new appreciation

of what artists do. It's not reporting. It's not journalism. It is creating

a parallel reality to our lived reality. That's the parallel reality with

all of the complexity of life's meanings created by art. That's really

why art exists of course – to make those kinds of meanings – so

totally different from the meanings in the newspaper or the evening news.

Thank God for that.

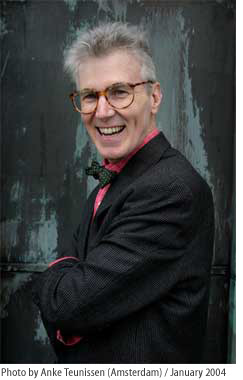

To read more about the back story of Ray Carney's research and publication process, click here and here and here.

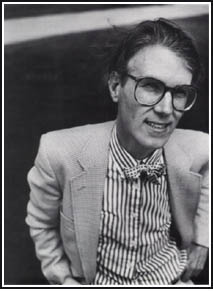

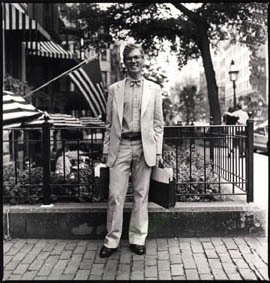

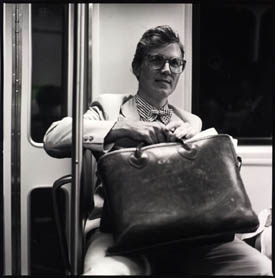

This page contains

an excerpt from an interview with Ray Carney. In the selection above,

he talks about his research process. The complete interview is available

in a new packet titled What's Wrong with Film Teaching, Criticism,

and Reviewing – And How to Do It Right, which covers many other

topics. For more information about how to obtain the complete text of

this interview and two other packets of interviews in which Ray Carney

gives his views on film, criticism, teaching, the life of a writer, and

the path of the artist, click

here.

For

an illustration of how not to do research, read the interview

with Ray Carney about Charles Kiselyak's shabby, shoddy A Constant

Forge (aka A Constant Forgery) documentary on Cassavetes'

life and work, by clicking

here.

|