Gena

Rowlands is devoted to denying the realities of Cassavetes’ life

and work and to creating an unreal, untrue myth. Not surprisingly, given

the star-struck Hollywood culture in which we live, it has been all too

easy for her to find sycophantic collaborators willing to do her bidding

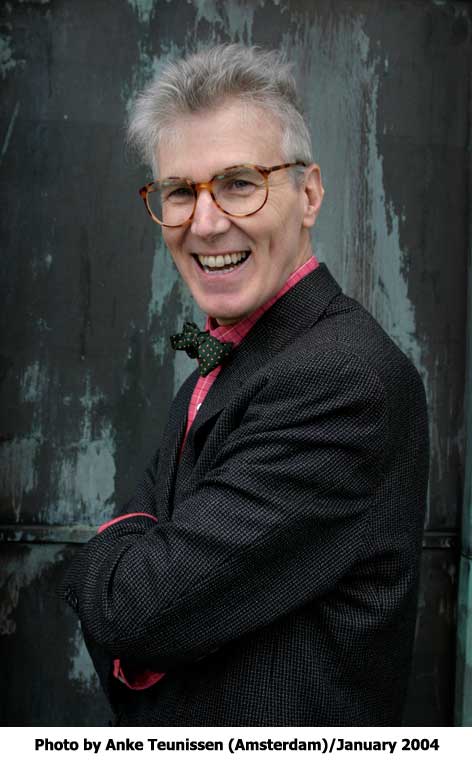

and tell the story the way she dictates. Prof. Carney has stood out from

the crowd in his attempt to fight for the truth. Gena Rowlands has waged

a campaign devoted to savaging Prof. Carney's reputation for telling the

truth about John Cassavetes' life and work. She is terrified of the truth

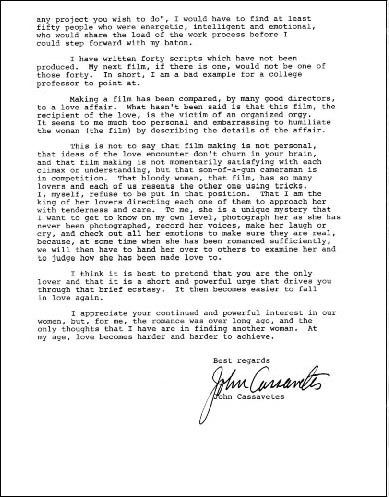

and interested in covering it up and denying it. Click

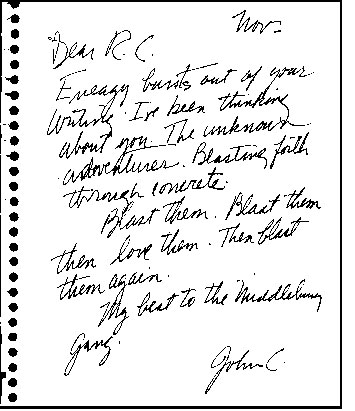

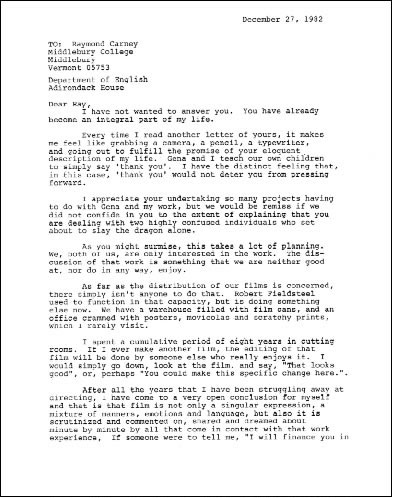

here for a glimpse of what Cassavetes was really like as a person

and an illustration of the kinds of facts that Rowlands is retaliating

against Carney for revealing. Her treatment of his Shadows and

Faces finds, and her insistence that Criterion remove his name

from the Cassavetes box set that he spent more than eight months helping

to create are part of her attempt to silence him.

Click here to read about Gena Rowlands's perpetuation of a Disneyland version of Cassavetes' life and work, her attempts to control what is written about Cassavetes, and her retaliation against scholars who try to tell the truth. For a counter-example

of how research should be done, see Ray Carney's description of how he

researched and wrote his Cassavetes on Cassavetes and Shadows

books, click

here.

To

read a chronological listing of events between 1979 and the present connected

with Ray Carney's search for, discovery of, and presentation of new material

by or about John Cassavetes, including a chronological listing of the

attempts of Gena Rowlands's and Al Ruban's to deny or suppress Prof. Carney's

finds, click

here. Click on page 5 (2006 - 2007) to read about two other hero-worshipping, star-struck, sentimental biographical portraits of Cassavetes.

To read another

statement about why Gena Rowlands or anyone else who acted in Cassavetes'

films or someone who knew Cassavetes is not the ultimate authority on

the meaning of his work or on how it should be cared for or preserved,

click

here.

To read about

Carney's being blackballed by Rowlands from contributing to another DVD

project, and about Seymour Cassel's being put in his place and, at Rowlands's

behest, making (foolish and incorrect) comments that "there is no

first version of Shadows" in the voice-over commentary to

the Shadows disk, click

here.

Click

here for best printing of text

CHARLES

KISELYAK'S CONSTANT FORGERY

FIGHTING FOR TRUTH

IN OUR CULTURE OF UNREALITY:

THE CHALLENGE OF DOCUMENTARY FILMMAKING

(An Interview with Ray Carney)

There

are a number of documentaries about Cassavetes. Can you talk about them? There

are a number of documentaries about Cassavetes. Can you talk about them?

I’d rather not.

Why not?

None of them is very good.

It’s a depressing subject.

Have you

seen all of them?

Oh, yeah. I was even the

scholarly advisor on one and wrote the script.

Which one?

Charles Kiselyak’s A

Constant Forge.

I’ve seen it. I

like it.

I call it A Constant Forgery.

I take it that means you

didn’t like it?

It’s a joke. It gives

a completely romanticized picture of Cassavetes. Ezra Pound used to

say that if you wanted to see how bad the encyclopedia was, you should

read an entry about something you knew really well. Then you could

see how far off all of the other entries are. I’m sure

everyone has had a similar experience at some point in their lives

with the newspaper. That when you actually were at an event you later

read an article about, you realized how biased or limited the treatment

of everything was. Well, it’s the same with Cassavetes.

If you know nothing about Cassavetes’ life when you see Kiselyak’s

film, it seems great. But if you know anything, you realize how unbelievably

superficial it is.

I’m not a big fan of

those formulaic, one-size-fits-all biographies that air on MTV, A&E,

or PBS, but, to tell you the truth, the ones I’ve seen about

Lucy and Ricky, Louis Armstrong, and the BeeGees are deeper and more

perceptive than Kiselyak’s movie.

I think it’s a difficult

genre to succeed in.

What do you mean by that?

It’s hard to get at

the truth. Everything works against you—both human nature and

the nature of filmmaking.

Why is that?

Original sin.

No, seriously….

The films that have been

made about Cassavetes are slipshod and superficial for the same reasons

most other things in our culture are slipshod and superficial. The

filmmaker’s laziness, stupidity, cravenness, cowardice, fear,

desire to flatter, need to please.

Look, the fallacy is that

if you take a camera and put it in front of a bunch of people who knew

Cassavetes and ask them to talk about him and get it all down on film,

you’ve made a movie about him. It just doesn’t work that

way. That’s a recipe for getting almost nothing valuable. There

are all sorts of things that get in the way of truth.

Like what?

Well,

start by considering who is interviewed. If you are dealing with an

actor or a director, most of people you’re going to be interviewing

are actors. Not exactly the intellectual heavy-lifters in our culture.

On top of that, the people Kiselyak chose to talk to were all friends

of Cassavetes—in the case of people like Seymour Cassel or Lynn

Carlin or Lelia Goldoni, people who owed their careers to him. Now

what are they going to say? Nothing unflattering or critical. That’s

for sure. Well,

start by considering who is interviewed. If you are dealing with an

actor or a director, most of people you’re going to be interviewing

are actors. Not exactly the intellectual heavy-lifters in our culture.

On top of that, the people Kiselyak chose to talk to were all friends

of Cassavetes—in the case of people like Seymour Cassel or Lynn

Carlin or Lelia Goldoni, people who owed their careers to him. Now

what are they going to say? Nothing unflattering or critical. That’s

for sure.

So what do you get? Sound

bites—a series of short anecdotes that weren’t true the

first time they were told thirty years before. You can hear the same

set of stories about Steven Spielberg or George Lucas on Charlie

Rose every week—or at any film festival Q&A—just

change the names: “What was it like to work with X, Y, or Z?” —“Oh,

he/she was wonderful. Such a creative, wacky guy/gal.” And the

ending is always the same: “How lucky I was to work with him/her.” It’s

a cartoon version of life and art.

What kind of understanding

can you get from a bunch of funny stories anyway? Save them for a dinner

party! We’d detect the silliness instantly if someone did this

to something we really truly cared about. Can you turn your relationship

with your boyfriend into a series of anecdotes? Can you turn your understanding

of Bach or Shakespeare into them? “Oh that Bach, he was so much

fun to be around, such a wild and crazy guy. I remember the time....” [laughs]

If you were dealing with anything but film it would be obvious how

trivial a bunch of anecdotes are in understanding art. But for some

reason we don’t detect the fraudulence if we’re talking

about film. It’s probably because we have such a low opinion

of the art to start with.

I guess talking

to Gena Rowlands would be the exception.

That’s another fallacy.

Why do we think the filmmaker’s 74-year-old widow has all the

answers? Do we ask Hitchcock’s widow about the meaning of Vertigo?

Do we ask Beatrice Welles about Citizen Kane? Would we ask Anne

Hathaway what Hamlet was about? We don't ask Lady Agnew to interpret

John Singer Sargent's portrait of her. Just because you were there

when something was done, doesn't make you an expert on it. Someone

who acted in a movie doesn't necessarily have a deep understanding

of the character or the film. It's an unfortunate but true fact that

Gena Rowlands doesn’t have a particularly deep understanding

of the films. Listen to the commentary she did for the DVD of Minnie

and Moskowitz if you have any illusions about that. And what she

knows about Cassavetes the person, she’s not telling.

I’m not sure how

to take your comments. Are you saying that people shouldn’t

make documentaries about filmmakers?

No. My point is that getting

something truthful, deep, perceptive in a film—any film, a feature

or a documentary—involves more than plunking a bunch of movie

stars down in front of a camera and asking them to tell stories. It’s

a challenge—because they will always be more interested in looking

and sounding good—or getting a laugh—than in telling you

something complex and insightful and true. Particularly movie stars—who

are masters at playing for a camera.

But, listen, don’t misunderstand:

I’m not blaming the people interviewed for the superficiality

of the documentaries. They are just being obliging and saying what

they are able to. The failure is the filmmaker’s, not theirs—because

it’s the filmmaker’s duty to dig beneath the surface.

And the problem is not limited

to movie star commentary or documentary films. Almost nobody tells

the truth in this sort of situation unless you force them to. We live

in a haze of clichés most of our lives. Think of political rallies.

Or what goes on in the classroom. Most people don’t really think unless

you make them do it.

But you can make someone

think. You can break through the clichés if you work at it.

But to do that, you have to know your subject inside-out. That was

the problem with Kiselyak. He knew too little about Cassavetes and

was too in awe of the people he was interviewing to detect when he

was being fed a line of bull.

I

thought you said you were the scholarly advisor on the film. Why didn’t

you tell him this? I

thought you said you were the scholarly advisor on the film. Why didn’t

you tell him this?

I told him but he wasn’t

interested. It represents such a different point of view from his own,

that I don’t think he could even hear what I was saying. Bear

with me. You have to know a little background to understand this. Kiselyak

began this project with only a passing knowledge of Cassavetes’ work.

He knew even less about Cassavetes’ life. He is a Los Angeles

free-lance “industrial” filmmaker. He makes documentaries

for a living. From what he’s told me, he’s mainly worked

for Pioneer. He makes documentaries to be included with their video

releases. He was hired to do the Cassavetes film to accompany Pioneer’s

release of the Cassavetes box set—though after the documentary

was completed Pioneer cancelled the box set because they didn’t

think they’d make enough money on it. The documentary was just

another job to him. He was doing it strictly for the money.

He called

me up when he got the assignment and confessed that he had not seen most

of the films and didn’t know very much about Cassavetes. He asked

me to fill him in on what he needed to know, who he should interview,

what documentary footage of Cassavetes was available, etc. etc.. He asked

me if I would be the scholarly advisor.

The events that followed taught

me a few lessons about the power of money in our culture. Here I was—someone

who had spent a lifetime studying Cassavetes’ work, someone who

had struggled year after year to get books and essays published against

all sorts of resistance, who had ultimately had to finance several

of them at my own expense to get them out there, who had spent tens

of thousands of dollars of my own money to celebrate and promote Cassavetes’ work.

And I get a phone call from this guy who hasn’t even seen all

of the films, and knows almost nothing about Cassavetes except what

he read on the Internet Movie Database, and he tells me he has been

given a lot of money—I later learned he spent something like

$200,000—to make a movie about him.

It kind of took my breath

away. This guy didn’t think he had to have seen the movies to

make his film. He wasn’t doing it out of passion and conviction.

It was a job.

This is a world I had almost

no contact with up to this point. I was so naïve. I had never

even thought of someone doing something like this strictly for the

money. Of course I’ve since realized that that’s the way

a lot of things are done. Even books. But it’s completely different

from the way I work.

How

long ago was that call? How

long ago was that call?

Oh, a long time ago. Back

in 1999 I think. It was the beginning of a long saga. I’m a little

older and wiser now. A little less innocent.

What do you mean?

Well, obviously he had called

the right person. I spent days, weeks, months briefing him. I put him

in touch with crew members and people who had known Cassavetes. I searched

out documentary footage—and found some great stuff by Andre Labarthe

and Tristam Powell. I sent him essays and books I had written. And

then got ripped off.

Ripped-off?

It’s the story of my

life. Dumb, da-dumb, dumb. I did hundreds of hours' worth of work for

him. I sent him material—information that no one else on the

planet had. I put him in touch with people to interview. I located

documentary material for him to include in his movie. I send him a

shortened, edited form of my Cassavetes on Cassavetes book,

which hadn’t been published at that point, where Cassavetes talks

about his life and work in his own voice, which ultimately became the

voice-over narration for the film.

He assured me over and over

again on the phone, in face to face conversations, and by email that

my collaboration would be handsomely acknowledged and remunerated.

But since I never got a formal contract putting it all in writing,

it all got forgotten in the end.

What

do you mean? What

do you mean?

I mean that all he did was

insert a brief mention of my Cassavetes on Cassavetes book at

the end of the credits, after most people have stopped watching. Nothing

else that he had promised. No credit as the scholarly advisor. No credit

as the script writer. And of course not a penny for any of it.

Looking back on it now, I

should have realized I was being set up for a massive scholarly rip-off

when he was doing on-camera interviews and made me pay my own expenses

to fly in and be interviewed.

What do you mean?

Well, at the point Kiselyak

was scheduling on-camera interviews, it became pretty obvious that

he wasn’t interested in digging into Cassavetes’ life and

work in a meaningful way, but merely in getting the biggest names he

could to appear in his film. He would call me up and tell me what a

coup he had scored in getting Sean Penn. Peter Falk, Ben Gazzara, Jon

Voight, or someone like that. He spent months flying around the country

pursuing Scorsese! But he never did get him. [laughing] The point was

to get “names” into his movie. And I wasn’t a “name,” so

when it came time to interview me he told me if I wanted to be on camera,

I should please pay my own expenses there and back. It was a complete

movie-star suck up, and I wasn’t a movie star.

Did

you have input into who he interviewed? Did

you have input into who he interviewed?

I provided some of the contact

information—and also tried to move him beyond celebrities. I

gave him names of these really interesting people who knew Cassavetes—crew

members, drinking buddies, friends; a few of the names I gave him got

in the film—Tom Noonan, Lelia Goldoni—but he wasn’t

interested in most of them because they weren’t famous. When

I explained the value of having the other kind of people in the film,

lower-level people who could talk more personally, less guardedly,

more intimately about Cassavetes the man, I don’t think he could

understand where I was coming from.

Why?

He’s a Hollywood person.

He lives in Los Angeles. He is impressed by big-names. In that respect,

he’s as star-struck as a teenager in Omaha. He doesn’t

understand any other way of being. His proof to himself that he is

doing something important is that he got an interview with “Columbo.” And,

speaking more practically, he’s afraid that no one will watch

his movie if it doesn’t have “name” interviews. It’s

what gets you on the Sundance Channel.

He used to call me up and

tell me stories about how he got to be friends with Oliver Stone by

making his movie about him. After he did this film, he would call and

tell me when Rowlands invited him up to the house for drinks. It really

mattered to him. I thought it was comical and a little pathetic.

Couldn’t you talk

to him about the star-struck nature of film culture?

I said it over and over again.

I laughed out loud when he told me how much time he was spending trying

to chase Martin Scorsese down to interview him. But he just didn’t

seem to understand.

Couldn’t you work

it into your film interview?

Saying something on camera

doesn’t get it into the film. Kiselyak filmed something like

three hours of me talking. Though I never sat down and tallied it up,

I’d estimate that something like three or four minutes made it

into the film. He probably didn’t want to cut into Sean Penn’s

time.

What do you think of the

poetic quotes?

Aren’t they embarrassing?

They make me cringe. It’s always amusing to see one of these

Hollywood types try to be “deep.” Try to be “serious.” I

have no idea what they mean. Even the title of the movie seems silly

and pretentious to me. What’s a “constant forge” anyway?

[laughing] I can understand “constant forging” by a “constant

blacksmith,” but what does it mean to call the forge itself constant?

You have to admit that

the end, where Cassavetes sings, leaves you with a lump in your throat,

doesn’t it?

I put Kiselyak in touch with

the guy who had those tapes: Bo Harwood. It’s great to hear Cassavetes’ voice.

The best moments in the film are when Kiselyak steps aside and simply

shows footage of Cassavetes performing for the camera—or for

the microphone in this case. I agree that the song is interesting.

But the film itself does nothing to dig into what it reveals in terms

of his life and work. The lump in your throat part of it is just a

cheap melodramatic effect. A way of ending the movie with a sentimental

twinge. The old voice from the grave device.

Can you be more specific

about your problems with the film?

Sure. But as I already said,

you won’t see them if you don’t have some independent base

of knowledge to check the film against. The less you know about Cassavetes,

the better Kiselyak’s movie looks; the more you know, the more

you see how evasive and superficial it is. Kiselyak himself still probably

doesn’t see the fraudulence of what he did because he still doesn’t

know enough about Cassavetes' actual personality.

Maybe

that’s the reason I react so strongly against the final singing

stuff. Because I see it as being of a piece with the rest of the movie

in terms of trying to sell us this sentimental, soap-opera version of

who Cassavetes was. It’s not true. It’s a fairy-tale account.

Kiselyak doesn’t come within a thousand miles of capturing the man

who actually made those tough-as-nails movies. Maybe

that’s the reason I react so strongly against the final singing

stuff. Because I see it as being of a piece with the rest of the movie

in terms of trying to sell us this sentimental, soap-opera version of

who Cassavetes was. It’s not true. It’s a fairy-tale account.

Kiselyak doesn’t come within a thousand miles of capturing the man

who actually made those tough-as-nails movies.

Almost all of the interesting

sides of Cassavetes' personality and all the important events and relationships

in his life outside of the films are missing: Where is his relationship

with Rowlands? Where is his relationship with his family and his friends?

Where is the rest of his life? He doesn't have one! And where is the

rest of his personality, his behavior, his character? Where is the

clown and show-off? The fast-talking wheeler-dealer? The hustler and

con-man? Where is the alcoholic? The demon-haunted loner? The womanizer?

The charmer? The bullshit artist? Where is Cassavetes the suspicious,

the sarcastic, the nasty and vengeful—your worst nightmare if

you dared to double-cross him, question his judgment, or get in his

way? Where is the Cassavetes of tears and rages and knock-down, drag-out

fights?

The result of leaving out

all of this is the rankest of hero-worship. Cassavetes has no shortcomings

and no flaws. He has no tangibility, no reality. From Kiselyak's movie,

you'd think Cassavetes was some kind of disembodied spirit of cinema,

with no problems, no doubts, no struggles, and no existence outside

of his movies. Even The Glenn Miller Story and Lust for Life are

deeper than this! They at least understand that art doesn't emerge

from an artist's head full-blown, full-grown. They understand that

human beings make it—complicated, flawed, confused, mixed-up

human beings.

Constant Forge is just

as sentimental in its treatment of the production and release of the

films. Cassavetes is a barrel of laughs: his crews are one big happy

family; and making the movies is a gigantic party. Wow. Hey, guys,

let’s all go make a movie. It sure is fun! All of the difficulties

of fund-raising, production, promotion, distribution, and exhibition

are left out. Where are the struggles with cast and crew? The shouts

and arguments during the shoots? The firings of crew members? The fights

with Rowlands over the financing? The fights over her acting? The critical

abuse? Where are the jeers and cat-calls? Where are the financial losses?

The sheer work, the ballsiness, the guts of making the films and fighting

to get them into theaters is all left out. It’s a Disney movie.

It might as well be the Ron Howard story.

Most glaringly, there is virtually

no intellectual content to the film. No ideas. No cultural history.

Nothing about the state of American independent film in the 1960s and

1970s. Nothing about what was happening in other arts like jazz and

expressionist painting, arts that are related to what Cassavetes was

doing in film. Nothing about the stupidity of Hollywood. Nothing about

American society. Nothing about the differences between art and entertainment.

A bunch of funny stories and clever anecdotes just don't cut it. It's

the talk show version of Cassavetes' life. Ultimately, it's an insult

to Cassavetes' work and art to reduce it to funny stories, to strip

the ideas, the history, the circumstances away from it.

Was any of this in the

material you gave him?

Yes, but it was left out

of the film. Even in terms of the voice-over script, he heavily edited

what I gave him to maximize the “happy face” side of things.

Does leaving out things

like that really matter?

A lie is a lie is a lie.

And lies will kill you. Our culture is dying of lies. Is everything

PR? Is everything politics? Is everything bullshit? Even Cassavetes’ life

story? Even an account of who he was and how he made his movies? He

devoted his life to truth-telling. Is the truth too dangerous to grapple

with? You know, the effect of lying in a documentary like this is even

worse than the effect of lying in a feature film, because we already

know that Hollywood movies sentimentalize, soften, purify reality.

But young filmmakers will watch this movie and fall for its lies. And

then they will think they are not right or normal, because their lives

are not this way.

Of course I don’t have

to point out that it’s particularly ironic to make this kind

of movie about this kind of filmmaker—to be sentimental about

the least sentimental filmmaker who ever lived.

That’s

not really what I was asking. What I meant was don’t Cassavetes’

films stand outside of these personal issues? Does it matter what kind

of person he was or how he made his movies? That’s

not really what I was asking. What I meant was don’t Cassavetes’

films stand outside of these personal issues? Does it matter what kind

of person he was or how he made his movies?

If Cassavetes was a Hollywood

hack, turning out mass-produced confections in a corporate environment,

it wouldn’t matter. We don’t need to know about Thomas

Watson’s personality to understand IBM’s computers. But

we’re talking about the most personal filmmaker America has ever

had. These are the only things that do matter. Cassavetes’ crazy

rages, insecurity, sense of rivalry, and all the rest throw a lot more

light on what these films mean than a parade of comical anecdotes do.

Heck, I’ll go further: I’d say you can’t really understand

Freddie, McCarthy, Moskowitz, or Mabel Longhetti in the deepest way,

without understanding Cassavetes’ personality.

This is not about muck-raking

Cassavetes' life. I am not interested in being an Albert Goldman or

Kitty Kelley. This is about understanding where the art came from.

It's about understanding the art. I am not interested in the life but

the work. The life changes your understanding of the work. You can't

understand the films without understanding Cassavetes' life and personality.

Of course, when I tried to say this on the Criterion disks, I was fired.

That process of understanding is what Rowlands wants to prevent and

Kiselyak wasn't interested in in the first place. Just the way they

do with George Bush or John Kerry, people prefer the PR version. It's

easier, neater, clearer, simpler. Truth is harder and more complex.

That complex knowledge is what I've devoted my life to.

Can you be more specific

about how Charles Kiselyak could have gotten these things into his

film?

Sure. Start with who he interviewed.

Kiselyak rounded up the usual suspects—the same people you’d

pick to speak at Cassavetes’ memorial service. How about including

a few people who would talk about him more critically? Erich Kollmar shot

Shadows and has never been paid a penny for his work because Cassavetes

turned on him after the film was complete. How about asking Kollmar to

tell what happened? David Pokotilow, who co-stars in Shadows, was

treated the same way. How about interviewing him? How about interviewing

Caleb Deschanel, who was D.P. on A Woman Under the Influence, until

Cassavetes threw him off the film? He has lots of stories to tell about

the way the shoot was conducted. How about interviewing John Badham and

Richard Donner and Ned Tannen—directors and producers who crossed

swords with Cassavetes in the 1970s. They would tell you things that don’t

jibe with the Lives of the Saints.

But even with the people he

interviewed, Kiselyak squandered his opportunity. Jon Voight tells

a silly “chicken story” about rehearsing the play version

of Love Streams. Another wild and crazy guy anecdote. Wow. But

what Kiselyak never asked Voight was why if Cassavetes was such a great

guy, Voight disliked working with him and distrusted his direction

so much that he pulled out of the film shoot two weeks before it was

scheduled to begin. Cassavetes had to step in to play the lead himself.

Or here’s another example:

Kiselyak interviewed Rowlands at length, but never asked her about

the verbal abuse her husband heaped on her during the shoots. A

Woman Under the Influence was especially awful. It was so bad she

could never bring herself to watch the movie.

But to ask these sorts of

questions, you’d have to know something before you went into

the interview. You’d have to have done some homework. And also

be brave enough to ask the questions on camera.

Do you know how Rowlands

felt about Kiselyak’s film?

She loved it! She still loves

it! My reservations about including it in the Criterion box set—and

I expressed them very politely, very deferentially—are one of

the reasons she had me fired from that project. Moral: don’t

disagree with Gena.

(Click

here to read about Rowlands's attempts to force Carney to suppress

his discovery of the first version of Shadows. Click

here to read

more about Carney's work on the Criterion Cassavetes box set and

Criterion's decision to let Rowlands censor what got into the set

and have Carney fired from the project. Click

here to read about

Rowlands's attempts to force Carney to suppress his discovery of

the long version of Faces.)

Why

would she like something that was shallow and superficial? Why

would she like something that was shallow and superficial?

That's why. She liked Kiselyak's

movie precisely because it's the PR version of Cassavetes' life. Movie

stars telling funny stories about a wild and crazy guy. She has a very

definite idea of what should and should not be said.

You can think of it as that

kind of Norma Desmond syndrome that afflicts big movie stars when they

start believing their press releases, their publicist, and their star-struck

fans, and confuse themselves with royalty—that feeling that they

are entitled to stage-manage reality, that intolerance of anyone who

has an independent view of anything. She brooks no contradiction. That's

why I took a bullet for not playing lap dog. Sic the lawyers on me.

Have me fired from the Criterion project. Get Peter Becker to jump

through her hoops. God save the Queen!

There are lots of “ground

rules” when you interview her—things she won’t talk

about, questions she won’t answer. But, when someone like Kiselyak

is interviewing her, she doesn’t have to spell it out. He knows

without being told what to ask and what not to ask.

How?

The same way you do when

you talk to anyone.

What do you mean?

It really mattered to Kiselyak

that Rowlands liked his movie. I remember how he called me up after

he had sent her a rough cut and told me that the payoff was that she

had invited him up to the house for drinks. That really mattered to

him. He must not have gotten enough love as a child. He’s still

trying to get more. He was putty in her hands.

What

do you mean by that? What

do you mean by that?

It’s like I said about

Kiselyak being star-struck by Oliver Stone. If you are making a movie

about someone and are interested in being friends with them, you can’t

go into certain areas that might make them uncomfortable.

It’s fatal to want to

be liked or want someone’s approval when you do this sort of

project. It puts limits on what you can say and do. To be true to anything—in

art or life—you have to find a way of not caring whether people

like you or not. Cassavetes himself understood that, but it’s

a very rare perception. Most people want approval. Kiselyak desperately

wanted to please Gena. That’s lethal, if you are dealing with

someone like her.

You end up with an “authorized” biography.

The usual “celebrity bio.” Hollywood hagiography. It's

why some of my students have made a pun on Kiselyak's last name.

What is the pun?

I'll leave that to your imagination.

It's not that hard to figure out. Still puzzled? Here's a clue: start

with "kiss your ...."

So what is someone who

wants the whole story about Cassavetes to do?

I get hundreds of emails

every year asking variations on that question. I tell people that they

should invite me to come speak at their college, or, almost as good,

read my Cassavetes on Cassavetes, which at least touches on

some of the messy truth.

Why do you say “at

least touches on”?

Because there is a heck of

a lot more to say.

Gena

Rowlands is devoted to denying the realities of Cassavetes’ life

and work and to creating an unreal, untrue myth. Not surprisingly, given

the star-struck Hollywood culture in which we live, it has been all too

easy for her to find sycophantic collaborators willing to do her bidding

and tell the story the way she dictates. Prof. Carney has stood out from

the crowd in his attempt to fight for the truth. Gena Rowlands has waged

a campaign devoted to savaging Prof. Carney's reputation for telling the

truth about John Cassavetes' life and work. She is terrified of the truth

and interested in covering it up and denying it. Click

here for a glimpse of what Cassavetes was really like as a person

and an illustration of the kinds of facts that Rowlands is retaliating

against Carney for revealing. Her treatment of his Shadows and

Faces finds, and her insistence that Criterion remove his name

from the Cassavetes box set that he spent more than eight months helping

to create are part of her attempt to silence him.

Click here to read about Gena Rowlands's perpetuation of a Disneyland version of Cassavetes' life and work, her attempts to control what is written about Cassavetes, and her retaliation against scholars who try to tell the truth. For a counter-example

of how research should be done, see Ray Carney's description of how he

researched and wrote his Cassavetes on Cassavetes and Shadows books, click

here.

To

read more about the Criterion Cassavetes Box set, the eight months

Ray

Carney worked on it, and the removal of his name from the set,

even though almost all of his work still remains in it, click

here and here.

The

opinion of Xan Cassavetes, John Cassavetes' daughter and

the director of Z Channel and other works, about Ray

Carney's Cassavetes on Cassavetes, as relayed to Carney

by a friend in Los Angeles (stars indicate omitted personal

material):

"I

am still in LA, working on *** , which is coming along. Real

progress. This evening saw Z CHANNEL, a new documentary

by Xan Cassavetes. *** I spoke with her after the screening.

I thought you might like to know that she absolutely loves CASS

ON CASS. Says she sleeps with it. Says it's enabled her

to have conversations with her father she never had."

|

To

learn more about Ray Carney's Cassavetes on Cassavetes, click

here.

To

read a chronological listing of events between 1979 and the present connected

with Ray Carney's search for, discovery of, and presentation of new material

by or about John Cassavetes, including a chronological listing of the

attempts of Gena Rowlands's and Al Ruban's to deny or suppress Prof. Carney's

finds, click

here. Click on page 5 (2006 - 2007) to read about two other hero-worshipping, star-struck, sentimental biographical portraits of Cassavetes.

To read another

statement about why Gena Rowlands or anyone else who acted in Cassavetes'

films or someone who knew Cassavetes is not the ultimate authority on

the meaning of his work or on how it should be cared for or preserved,

click

here.

To read about

Carney's being blackballed by Rowlands from contributing to another DVD

project, and about Seymour Cassel's being put in his place and, at Rowlands's

behest, making (foolish and incorrect) comments that "there is no

first version of Shadows" in the voice-over commentary to

the Shadows disk, click

here. |