|

In

Praise of Impurity:

Thinking about Film, John Cassavetes,

and the Awfulness

of Film Criticism

Excerpts from an interview with Ray Carney by Jake Mahaffy

Published in Cinemad, February 2002

|

Best film surveys and textbooks invariably

list Citizen Kane and Battleship Potemkin as “the greatest

films ever made.” These two films' popular priority has more to do with

their formal and technical influence and a predisposition for accurate,

academic dissection than any relevance to actual, human experience. In

contrast, to the mutual extent his work is popularly unrecognized, John

Cassavetes' films defy categorization and constitute an extremely important

body of work.

John Cassavetes' creative medium is life

itself. His films record the awkward and indefinable reality of people

learning to live with each other. This is not hack psychology with crazy

camera-angles or political propaganda with Marxist match-cuts. What's

most important in his films are not technical innovations or plot tricks

but unspoken emotions. Cassavetes is relevant above and beyond the context

of any scholastic study of film history or criticism. His films relate

to real life, and a true study of his work can never be an exclusively

academic exercise.

Enter Ray Carney, a premiere proponent

of American independent cinema. With Cassavetes on Cassavetes (Faber

and Faber), Carney has spent over eleven years collecting and editing

John Cassavetes' creative biography from interviews, discussions, first-hand

accounts and personal conversations. This book is comprised of Cassavetes'

own words: his observations, insights, questions and ideas on filmmaking,

cinema, art and America. The book isn't just interesting, it's an inspiration

to anyone who cares about film as art.

In

this book we witness Cassavetes' character in-the-round: his quirks, compromises,

doubts and his persistence, intensity and loyalty without any pretense

to criticism or deification. His complex biography is presented in meticulous

detail. And the book is replete with his eloquent and encouraging words

for other artists who struggle to make something honest and true in the

face of incomprehension and indifference. I think this book is as full

of elation and despair, insight and inspiration, as Cassavetes could have

wished

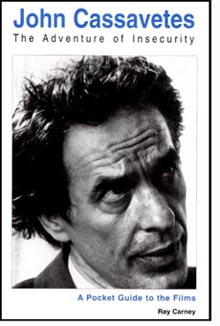

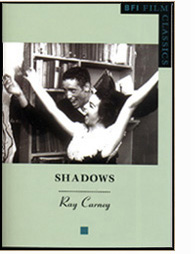

Carney is

also publishing two other books at the same time: a behind-the-scenes

study of the making of Cassavetes' first film, Shadows and a viewer's

guide to his work, John Cassavetes: The Adventure of Insecurity.—JM Carney is

also publishing two other books at the same time: a behind-the-scenes

study of the making of Cassavetes' first film, Shadows and a viewer's

guide to his work, John Cassavetes: The Adventure of Insecurity.—JM

Jake

Mahaffy: Cassavetes on Cassavetes and your book on Shadows

give insight into Cassavetes' personal life and creative practice, both

how he related to people on a day-to-day basis and how he related to actors

and crew, working on a film production. We get a very real, human portrait

in both books. One aspect of Cassavetes' character that comes across is

unsettling. He was obviously very sensitive and perceptive, and able to

share people's fears and most subtle emotions in film. But it seems he

could just as readily use that knowledge to manipulate and intimidate

people, and not even for noble artistic purposes, but just for it's own

sake...

Ray Carney: Cassavetes was not a simple person. At the point at which

I began doing research I had heard so many stories – the “I rode

with Billy the Kid” tales – of how exciting it was to work with

him or be around him. I had hosted scores of events at film festivals

and listened to the press release version of his life disseminated by

his family and close friends. No one ever said anything bad about him

– particularly Gena Rowlands, who is extremely protective of his

memory for all the obvious reasons. I had this

rose-colored vision. Then I began lifting the carpet, talking to

dozens of people I hadn't met before this. There was a lot of stuff underneath.

Things I didn't want to know. Things I wished I hadn't discovered.

There was a lot that was wonderful about Cassavetes that no one

ever denied, and that I still believe to be true. There is no question

that he is one of the great twentieth-century artists – in any medium.

He was a visionary and a dreamer, a passionate, nonstop talker who was

exciting to listen to. He was a born charmer, with the charisma of a Svengali.

People loved to be around him. They basked in his energy. He inspired

them and could talk people into doing seemingly anything. It took those

qualities to make the movies. He had to throw a lot of magic dust around

to keep people working long hours without pay. He had to play with their

souls to motivate them.

But as I dug deeper, I was forced to recognize that you can't have the

positive without the negative, the virtues without the corresponding vices.

Cassavetes was a super-salesman, a Pied Piper, a guru – but

he was also most of the other things that come with the territory. He

was a con-man. He would say or do almost anything to further his ends.

He'd lie to you, steal from you, cheat you if necessary. He could be a

terror if you got in his way. If he liked you

or needed you, he was a dream – kind,

thoughtful, generous; if you crossed him, he was your worst nightmare.

To put it comically, you might say that he had a short man's complex or

a Greek man's macho streak. The positive side is that he was a fierce

competitor and a perfectionist. When it came to making movies, nothing

could make him compromise his vision. The negative side was that he was

incredibly proud and temperamental. He would turn on you if you even politely

questioned his judgment or wanted to do something different from what

he did. It was good he wrote, directed, and

produced his own work, because no one was less of a team player. He couldn't

deal with authority. He had to be the boss, the center of attention,

the star of the show – on and off the set. If

he didn't get his way he threw temper tantrums and behaved childishly.

When I began, I had already sketched the portrait I wanted to paint in

my mind. Cassavetes would be a paragon of sensitivity and perceptiveness,

using his characters to analyze male sexual and social dysfunctions. Then

person after person told me, asking me not to put their names in print

as having said it, that he resembled his characters in lots of ways. In

short, he could be as difficult and macho, as

bullying and emotionally immature, and as much a bullshit artist as Freddie

and McCarthy in Faces. He could be as much a clown and show-off,

hidden behind a wall of “routines” as Gus in Husbands. In the years

before he made Shadows, he was as much a slacker and moocher off

his older brother as Bennie is off Hugh. At the point he made The Killing of a Chinese Bookie and Love Streams,

he had a lot in common with Cosmo and Robert Harmon. He was as much of

a lone wolf, as spookily withdrawn and solitary. I had begun by thinking

of films like Faces and Love Streams as being based on Cassavetes'

run-ins with shallow, vain, screwed-up Hollywood executives and artist

wannabes; but I had it shoved in my face that

his characters were not someone else; they were him and

his best friends.

What I was discovering violated everything I wanted to believe about great

artists. I had always thought of them as somehow better than the rest

of us – wiser, kinder, more aware, more sensitive.

The artist functioned somewhere above the crummy, confused, disorganized

world the rest of us live in.

Does that sound stupid or naive? Well,

that's what I sincerely believed. I needed Cassavetes to be a wonderful

human being. I didn't want him to be petty and fallible. I fought the

truth tooth and nail. I didn't want to believe it. It

was a real crisis for me. I lost sleep worrying about it. I spent hours

talking it over with friends, trying to understand how it could be true.

I almost aborted the project at several points because of it.

JM: So you found out he wasn't perfect. But no one is!

RC: It's a larger issue. I discovered

a lot of stuff that seemed really very immature, very adolescent, very

sad in a way. Though no one talks about it in public on the record, in

private his friends and children tell endless stories of unprovoked rages,

insane jealousies, petty vendettas, passionate loves, paranoid fantasies,

tearful fits of despair. It actually validated the view of Cassavetes

that critics like Kael, Kauffmann, and Simon had. In their reviews they

implied he was boorish and offensive, and I found out that he was! RC: It's a larger issue. I discovered

a lot of stuff that seemed really very immature, very adolescent, very

sad in a way. Though no one talks about it in public on the record, in

private his friends and children tell endless stories of unprovoked rages,

insane jealousies, petty vendettas, passionate loves, paranoid fantasies,

tearful fits of despair. It actually validated the view of Cassavetes

that critics like Kael, Kauffmann, and Simon had. In their reviews they

implied he was boorish and offensive, and I found out that he was!

Throughout his life, Cassavetes was known for his wild-man behavior. He

was delightfully nutty, and impetuous and impulsive to a fault. He seemed

capable of doing or saying anything to anyone, utterly fearless and heedless

of consequences. Sometimes the nuttiness manifested itself as a stunt

or a prank – like the time he chained himself to radiator at CBS

to attempt to force them to give him a walk-on in You Are There

or got mad at a receptionist and faked an appendicitis in her office (refusing

to give up the ruse, even when the paramedics showed up) or deliberately

made a scene in public just to see how people would react. This was the

actor who, after all, if he found himself with a spare hour or two on

his hands, would ride uptown in the bus loudly crying the whole way, and

then downtown loudly laughing, just to see how people responded. Or (in

anticipation of Seymour Moskowitz) approached women on the street he had

never seen before, insisting he knew them from high school or college,

trying to pick them up. Half of his friends thought he was nuts; the other

half adulated him, since even simply going into a bar with him became

a kind of street theater – Cassavetes would do something completely demented,

a crowd would gather, and craziness would ensue. And Cassavetes ate it

up. He was a born clown who loved to the center of attention (in fact

demanded to be). He was a Svengali with women. A guru with men. And took

full advantage of the power that accrued.

He turned life into fun and games. Of course the game was often not funny

for those who were its victims. The years he was trying to make it as

an actor are full of examples. There was the time a casting director rejected

him for a part because “no one would believe you as a murderer,” and Cassavetes

returned to his office a few hours later with a gun and threatened his

life: “You don't believe I can be a murderer? You don't think I can kill

you? I'll show you.” The young actor wasn't smiling and the agent was

so terrified he broke into tears. Or the time Cassavetes got mad at a

producer and tore up his office – overturning the desk, pushing the bookshelves over,

tearing up the rug, toppling everything onto the floor. It wasn't a joke.

There was hundreds of dollars worth of damage, and Cassavetes didn't stop

until the police came to arrest him. Wild, insane rages were common. Cassavetes

thought nothing of swearing, yelling, even throwing a punch when someone

dared to disagree with him. There were lots of brawls like the one in

that ends Shadows – in bars and on the street; and later on, lots of

yelling matches, with Rowlands, at home and in public. None of that was

a laughing matter.

It's no surprise that the films he went on to make in the following decade

are so intense emotionally. They are continuous with the emotionality

of his life. Cassavetes the person was unable to fit into society's categories

and polite roles, just as his characters are unable too. He was too alive,

too emotional, too fluid to be contained by a category, to behave properly

or correctly in society, just as they are. His own personal behavior,

in fact, was beyond anything you see Mabel, Myrtle, Sarah, or Lelia do

– at their most extreme.

His films, in effect, pose the same questions his life did. How do we

understand this sort of extremity? Is it crazy or inspired? Is it evidence

of creativity or just maddening self-centeredness? Does it point a way

out of the ruts and routines of life or is it just a sign of a rug-merchant,

a con-man, a hustler devoted to getting his own way? Do these theatrical

expansions of selfhood enhance, enlarge, and enrich personal identity

or open the flood gates to chaos? They are the questions figures like

Lelia, Moskowitz, Mabel, Myrtle, and many of Cassavetes' other characters

pose.

JM: So his personality is in his characters.

RC: Yes. But what I have just said makes it sound too theoretical. Let

me not mince words. Cassavetes may have been a brilliant filmmaker but

he was not always a great human being. As my friend Tom Noonan, who also

knew him, said to me once: “You know, all those people who worship him

as some kind of hero wouldn't have been able to stand being with him for

an hour.” He was too annoying. He needled Gena mercilessly. He pushed

people's buttons to see how they would react. He flew into rages if you

dared to cross him or disagree with him. He wasn't reasonable. He was

not a saint. He was closer to being a nut case. A wild man. Possessed

and out of control emotionally. A con-man who would use you if he could

benefit from it in some way. A child who threw temper tantrums, yelled,

screamed, and cried when he got upset. That's what threw me for

so long. How could a great artist be so screwed up, so immature, so self-centered

and willful?

But in the end it taught me important things. First, that the dancer is

different from the dance. Look at Bach, Beethoven, Picasso, D.H. Lawrence,

Robert Frost. None of them was an ideal human being. They were all cantankerous,

difficult people. Critics find that so surprising that they write books

about them “exposing” their moral flaws, as if it were the exception rather

than the rule. The mistake is that artists function by different rules

from what critics expect.

Second, he wasn't a clear-headed theorist of his own work. He forged his

work in his heart, out of his emotions. Not from his head and his ideas.

He used to say he discovered what his films were about when viewers told

him, and that wasn't false modesty. They didn't come from theories and

ideas, but from impressions, memories of things he saw and lived through.

What I ultimately understood that art could come not from clarity but

confusion; that work could be quarried from the imperfections of an artist's

emotional life. I ultimately realized that his fallible, flawed humanity

was not at odds with the greatness of his work, but the source of

it. Cassavetes' personality was a mess of unresolved moods and feelings.

He could be a romantic and a hard-driving businessman; a visionary

and a rug-merchant; an idealist and a ball-buster; generous

and self-centered; sensitive and tough – and he created characters

with the same complexity. He put his emotional confusions and contradictions

into them. At other times it seemed as if he parceled out different sides

of his personality into different figures. If Jeannie represented one

part of him, Chettie, Freddie, and Richard represented other moods and

feelings. Cassavetes' greatness as an artist was precisely that he wasn't

afraid to put everything that was in him in his movies. That's

what it means to say that his life is in his films, not as biographically

but emotionally.

Maybe that's a better starting point for thinking about most art –

not as coming from otherworldly clarity but this-worldly turbulence. Look

at Picasso's paintings. Listen to Beethoven's symphonies. The first thing

they teach us is that the greatness of the works is not their heavenly

clarity, but their all-too-earthly conflict. And the second thing they

teach us is that the greatest art is personal. It's not about someone

else. It's about them, their lives, their frustrations,

their loneliness. That's where critics invariably go wrong. Art

at its very greatest isn't a game of playing with genres or conventions.

It isn't all those arch, ironic things the critics read out of it. It's

a life or death struggle to express what you really are – in all

of its mess and turmoil. It's reality. It's close to home.

What I learned about Cassavetes ultimately violated everything our culture

tells us about movie stars and directors. Watch Tom Cruise on Oprah,

listen to a Barbara Walters interview with Meryl Streep, or Charlie

Rose or James Lipton sucking-up to Spielberg. The goal is to convince

us that they are just sincere, hard-working regular people like us – raising families, falling in and out of

love, buying groceries down the street, trundling the kids off to day

care. They're no different from you and me. Just folks. They are the same

charming, well-meaning schmos we think we are. That's why we are supposed

to like them. To say the obvious: that's poppycock – even if we're talking only about Hollywood

hacks. It's not even true of us ordinary people. We're all much weirder

than that.

And it was even less true of someone like Cassavetes. He was not the

man on the street. He was possessed by demons – of self-imposed

alienation, loneliness, self-destructiveness, ambition, frustration, anger

– but that's not a bad thing. It was the demons that gave him the

power to create such powerfully demon-driven protagonists, living their

own lives in states of emotional extremity. Look at the movies, for gosh

sake. Look at the fact that he made them, and kept making them –

against all odds, while almost every critic in America jeered. He didn't

care. He had a vision, a dream. He spent his life trying to build rockets

to fly to the moon in his garage. That should tell you something about

how crazy he was! And that's what's wrong with all those postmortem celebrity

interviews that tell us what a swell guy he was. OK. He was a great guy

at times; but he was a lot more than that or he wouldn't have been what

he was and done what he did. He was a maniac. He was nuts. He was a tough,

hard person. He was absolutely impossible to deal with when he wanted

you to do something for him. He didn't give a shit what the critics said

about him or his work. He was not Tom Cruise or Tom Hanks. He was

not all those things his admirers want to turn him into: warm,

fuzzy, cuddly, and loveable. He would have chewed up and spit out Oprah

and Rose and Lipton. Heck, he did with interviewers in his own day. I

have tapes of his appearances on talk shows of his own day. He was not

the charming, smiling guest they bargained for – and the hosts did

not invite him back.

Cassavetes gave me copies of some of his shooting scripts before he died,

and the shooting script of Faces makes the autobiographical side

of the film almost painfully clear. He wrote it at a time of deep frustration

and dissatisfaction with his life, and it is laced with incredibly personal

passages – perhaps too personal, since they were almost all cut

from the release print – in which Cassavetes puts his own feelings

in the mouths of his characters, particularly Richard Forst. But what

is most telling is how unresolved and contradictory the expressions are.

Forst expresses frustration deep with his marriage, but also talks about

the wonder of love and romance. Much of his speech is laced with disillusionment

and cynicism, but he also expresses hope and idealism in other passages.

He talks about loving to be around people; then switches to talking about

the need to get drunk to kill the pain of empty, meaningless social interaction.

It's almost more than I can bear to know about Cassavetes' emotional turmoil

at the point he wrote the movie. But it reveals a lot about the messy,

confused rag-and-bone shop of the heart his work came from.

JM: For Cassavetes, a film was a tool, a means to an end, not a self-contained

statement. It was a practical way of recording moments and expressions,

which were the real medium for him. He shied away from using the word

“idea” and preferred the word “emotion” to express the content of his

work. He thought ideas were the intellectualizing, the formulation of

experience, whereas emotions were an immediate, instinctive and direct

experience. Ideas as explanations are a step removed from actual experience,

and somewhere in-between a truth is lost….

RC: Cassavetes was not an intellectual.

He wasn't interested in theory or criticism. In fact, he really wasn't

much of a reader at all. Believe it or not, I don't think he ever read

Stanislavski. Remember the line in A Woman Under the Influence:

“Let the girls read”? – well, he left the reading to Rowlands! He

was a people-watcher and learned more from an hour of watching faces and

listening to voices in a restaurant than a library of books could have

taught him. He did not function analytically. He operated out of his guts,

his instincts about people, his feelings about life. RC: Cassavetes was not an intellectual.

He wasn't interested in theory or criticism. In fact, he really wasn't

much of a reader at all. Believe it or not, I don't think he ever read

Stanislavski. Remember the line in A Woman Under the Influence:

“Let the girls read”? – well, he left the reading to Rowlands! He

was a people-watcher and learned more from an hour of watching faces and

listening to voices in a restaurant than a library of books could have

taught him. He did not function analytically. He operated out of his guts,

his instincts about people, his feelings about life.

In fact, he probably wasn't aware that his characters represented parts

of himself or embodied his emotional confusions. All he probably thought

he was doing as he dictated his scripts was slipping into their skins

and trying to bring them to life, putting everything he felt and

knew into them. His obsessions, doubts, and uncertainties became

theirs.

In short, Cassavetes' insights came from life, not from theory –

which is of course the best place to get them. It's the opposite to how

most critics function, which is why a critic has to be very, very careful

about the conclusions he draws. The films didn't begin as ideas. Shadows

didn't begin as a study of “beat drifters” or “race relations.” It was

Cassavetes' effort to give voice to the mixed-up feelings he had as a

young man (particularly about his relation to his brother). Faces

and Husbands didn't originate as analyses of the “male ego” or

studies of the frustrations of “suburban life.” They were Cassavetes giving

voice to his own personal disillusionments about marriage, middle-age,

and his career. They were documentaries of everything he knew and felt

at that point in his life – not sorted out into a series

of “points” or “critiques” or “views.”

That's actually a fairly unusual way to proceed. La Dolce Vita was

released three years before Cassavetes wrote Faces, and has some

superficial similarities with it (as well as being referred to in it).

I sat through a screening the other night at Harvard and the scenes practically

had labels on them. This one was an attack on the idle rich. That one

was a critique of on the superficiality of journalists. This other one

commented on the vapidity of modern architecture. The majority of films

are organized this way. Look at Nashville, Welcome to the Dollhouse,

Magnolia, and American Beauty. They have theses.

They make points. The characters represent generalized views and

ideas – and the critics eat it up! They love abstract movies, since

they make their jobs easy. Films that originate in ideas can be translated

back into ideas with almost nothing lost in the translation. These films

are eminently discussible. You can write an essay about them. Because

ideas are abstract. They are simple. They say one thing. They stand still.

Cassavetes' work resists that kind of understanding. Every time we want

to lasso a character or a scene with an idea, it scoots away from us.

The incredibly detailed behaviors, facial expressions, and tones of voice

that comprise his scenes defeat generalizations. The characters in Faces

and Husbands are too changeable, too emotionally unresolved to

be pigeonholed intellectually. As Cassavetes says in Cassavetes on

Cassavetes, they may be bastards one minute but they can be terrific

the next. In A Woman Under the Influence just when we're about

to decide that Nick Longhetti is a “male chauvinist,” he says or does

something kind and thoughtful. Just when we want to turn Mabel into an

“oppressed housewife,” she sleeps with another man to show us she is not

under the thumb of her husband and has genuine emotional problems. The

racial incident at the center of Shadows invites an unwary critic

to view the main drama of the film as being about race, but the film's

narrative and characterizations subvert the attempt. The racial misunderstanding

at the center of the film is largely a device to create other, more interesting,

more slippery dramatic problems for them to deal with. The characters

are given such individualized emotional structures of feeling that it

becomes impossible to treat them generically as racial representatives.

We can't factor out their personalities. Character is at the heart of

Cassavetes' work, always displacing incident as the center of interest,

and the particularity of the characterizations in all of the films prevents

us from treating the characters' situations in a depersonalized way, which

is what ideological analysis always requires to some extent.

I'm convinced that this aspect of Cassavetes' work is the reason that

during his lifetime reviewers wrote off his work as being confused or

disorganized. They wanted to be able to label characters and situations,

and when they couldn't, decided it was the films' fault. They wanted to

be able to stabilize their relationship to an experience by being able

to maintain a fixed point of view on it. In Shadows, they wanted

to be able to conclude that Lelia and Ben were victims of racial prejudice;

in Faces, that the figures were being morally judged; in Husbands,

that the three men were being satirized. When the movies defeated

such easy relationships to the experiences they presented, the critics

wrote them off as muddle-headed, self-indulgent actors' exercises.

Cassavetes made things hard to understand. That's why a work of art exists.

Otherwise, you might as well write an essay about your subject. Real art

is never reducible to the sort of moral lessons and sociological platitudes

that Spike Lee or Oliver Stone give us or that reviewers and academic

critics want. Art speech is a way of experiencing and knowing far, far

more complex than the ways journalists, or history, sociology, or film

professors think and talk.

This

page only contains brief excerpts from an interview Ray Carney gave to

Jake Mahaffy. In the excerpt above, Ray Carney discusses his changing

conception of Cassavetes the man. The complete interview covers many other

areas. For more information about Ray Carney's writing on independent

film, including the entire text of interviews with him in which he gives

his views on criticism, film, and the life of a writer, click

here.

|