|

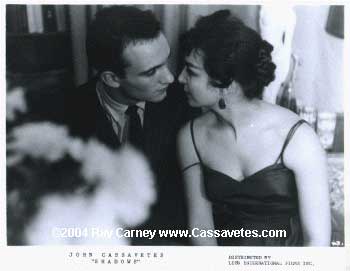

Though

most reviewers treated Shadows as being about race problems,

Cassavetes always thought of the film as more personal. Almost

all of the scenes

were based on his own experiences and feelings. In his early auditioning

days, Cassavetes had once sung "A Pretty Girl Is Like a Melody"

to introduce

a girlie line in the Hudson Theater and been humiliatingly told to "shut

up, sit down, and let the girls come on" in his place. Many of

the characters

had parts of him in them. Ben's aimless alienation and cruising for girls

was not only modeled on Cassavetes' own jobless drifting and carousing

with his two roommates in the early fifties, but figured a lonely, nighttime,

wandering side of his personality that endured throughout his life.

Lelia's

romantic impulsiveness, Rupert's and Hugh's belief that friendship was

more important than business, and Tom's tirade about colleges and

professors

all embodied aspects of his feelings and beliefs. Though the relevant

scenes were later cut from the print that comes down to us, it

is also

significant that Shadows initially focused on the idea that Tony

"stole" David's girlfriend, which tied in with Cassavetes' competitiveness

with other men about women. Hugh represented the side of Cassavetes that

felt drained by and resentful of the demands placed on him to do things

for others. (Cosmo Vitelli would later constitute an even more extended

self-portrait of this side of Cassavetes' personality – the part

of him that in his view of himself did everything for everyone else

and nothing

for himself.) Most profoundly of all, Ben's and Hugh's relationship mirrored

the relationship of Cassavetes and his older brother Nick. Hugh was

a

version of Nick – dutiful, responsible, hard-working and somewhat

frustrated; while Cassavetes was a version of Ben – a self-centered

slacker, who mooched off his older brother in the early part of the

decade, and then watched

him experience a discouraging series of setbacks to his career and finances

at the end of it. Though

most reviewers treated Shadows as being about race problems,

Cassavetes always thought of the film as more personal. Almost

all of the scenes

were based on his own experiences and feelings. In his early auditioning

days, Cassavetes had once sung "A Pretty Girl Is Like a Melody"

to introduce

a girlie line in the Hudson Theater and been humiliatingly told to "shut

up, sit down, and let the girls come on" in his place. Many of

the characters

had parts of him in them. Ben's aimless alienation and cruising for girls

was not only modeled on Cassavetes' own jobless drifting and carousing

with his two roommates in the early fifties, but figured a lonely, nighttime,

wandering side of his personality that endured throughout his life.

Lelia's

romantic impulsiveness, Rupert's and Hugh's belief that friendship was

more important than business, and Tom's tirade about colleges and

professors

all embodied aspects of his feelings and beliefs. Though the relevant

scenes were later cut from the print that comes down to us, it

is also

significant that Shadows initially focused on the idea that Tony

"stole" David's girlfriend, which tied in with Cassavetes' competitiveness

with other men about women. Hugh represented the side of Cassavetes that

felt drained by and resentful of the demands placed on him to do things

for others. (Cosmo Vitelli would later constitute an even more extended

self-portrait of this side of Cassavetes' personality – the part

of him that in his view of himself did everything for everyone else

and nothing

for himself.) Most profoundly of all, Ben's and Hugh's relationship mirrored

the relationship of Cassavetes and his older brother Nick. Hugh was

a

version of Nick – dutiful, responsible, hard-working and somewhat

frustrated; while Cassavetes was a version of Ben – a self-centered

slacker, who mooched off his older brother in the early part of the

decade, and then watched

him experience a discouraging series of setbacks to his career and finances

at the end of it.

Beyond these specific references,

the general subject of Shadows was close to Cassavetes' view of

his own situation at this point in his life. He thought of himself as

doing the same thing in his world as Lelia and Ben did in theirs. In

their

different ways, he and they were attempting to "pass" for something that

was not necessarily a reflection of their true identities. As would be

the case with all of his subsequent works, the issues in the film were

close to Cassavetes' heart. He could not satirize or mock characters

who

were so similar to him.

We tried to do Shadows

realistically – not Andy Hardy. I just was as tough and as mixed up and

screwed up as anyone else and made a picture about the aimlessness and

the wandering of young people and the emotional qualities that they possessed.

Years later, he would tell

me that I had written the only essay about the film that he ever

really

liked, because it treated the film as being "not about racial but human

problems".

The

story is of a Negro family that lives just beyond the bright lights

of Broadway; but we did not mean

it to be a film about race. It got its name because one of the actors,

in the early days, was fooling around making a charcoal sketch of

some

of the other actors and suddenly called his drawing Shadows. It

seemed to fit the film. The NAACP came to us to finance it, but we turned

it down. We're not politicians. One of the things that has to be established

when you're making a movie is freedom. Everyone will get the wrong idea

and say we've got a cause. I couldn't care less about causes of any kind.

Shadows is not offensive to anybody – Southerners included – because

it has no message. The thing people don't like is having a philosophy

shoved down their throats. We're not pushing anything. I don't believe

the purpose of art is propagandizing. The

story is of a Negro family that lives just beyond the bright lights

of Broadway; but we did not mean

it to be a film about race. It got its name because one of the actors,

in the early days, was fooling around making a charcoal sketch of

some

of the other actors and suddenly called his drawing Shadows. It

seemed to fit the film. The NAACP came to us to finance it, but we turned

it down. We're not politicians. One of the things that has to be established

when you're making a movie is freedom. Everyone will get the wrong idea

and say we've got a cause. I couldn't care less about causes of any kind.

Shadows is not offensive to anybody – Southerners included – because

it has no message. The thing people don't like is having a philosophy

shoved down their throats. We're not pushing anything. I don't believe

the purpose of art is propagandizing.

However idealized his attitude

may seem in hindsight, Cassavetes thought of race less as a biological

reality than an imaginative stance.

At the time I made Shadows

I wished that I was a black man, because it would be something so definite

and the challenge would be greater than being a white man. But now, American

black men are white men so there's no challenge and I don't really wish

to be that anymore. I don't know about other men's desires but it is my

desire to be an underdog, to win on a long shot, to gamble, to take chances.

Cassavetes was opposed to

the notion of art having a negative or satiric agenda, and to works that

mocked or denigrated their characters.

There is a great need in the

cinema for truthfulness, but truth is not necessarily sordid and not necessarily

downbeat. Unfortunately, the art films have dealt mainly with the evils

of society. But society is more interesting than rape or murder. I think

you can do more through positive action than in pointing out the foibles

and stupidities of man. Yes, any man is capable of killing any other man,

we know that, we don't have to stress that. To say that it's right and

normal, to continue to say it, to have society and the Establishment confirm

that view, is wrong.

Art films reach for the most

obvious fallacies of society, such as racial prejudice. That's been a

fault of the art film – devoting itself to human ills, human weaknesses.

An artist has a responsibility not to dwell on this and point it up, but

to find hope for this age and see that it wins occasionally. Pictures

are supposed to clarify people's emotions, to explain the feelings of

people on an emotional plane. An art film should not preclude laughter,

enjoyment and hope. Is life about horror? Or is it about those few moments

we have? I would like to say that my life has some meaning.

I think that there are certainly

many, many wonderful things to be written about in this day and age of

disillusionment and horror and impending doom. We must take a more positive

stand in making motion pictures, and have a few more laughs, and treat

life with a little more hope than we have in the past. Shadows

is a realistic drama with hope – a hopeful picture about a lower echelon

of society in the United States – how they live, how they react. The people

are hopeful. They have some belief. I believe in people.

The worst kind of art of

all, in Cassavetes' view, was the fifties "exposé".

I'm not an Angry Young Man.

I'm just an industrious young man. And I believe in people. I don't

believe

in "exposés", as exposés have just torn America

apart, and the rest of the world. I don't believe in saying that the

presidential

campaign is all phony, going inside it and looking at it. It's been going

on for years this way, but for the first time in history we're going

in

and saying, "Yeah, see what they do? See how they get votes? See

how this is done? See?" Human frailties are with us. People aren't

perfect. But

we have good instincts that counterbalance our bad acts. The main battle

is you don't make ugliness for the sake of ugliness. By attacking, constantly

attacking everything in sight, no matter what anyone does, it's not good

enough because it can't be trusted. And nobody, starting with the top

of our government, can be believed. Everybody is a phony. So if everybody's

a phony, what's the sense of going on, because there isn't anybody worth

making a picture about, talking about, writing about. There's no hope

in living and you might as well pack it all in and forget about it.

Why

should young people's minds constantly be filled with the corruption

of life? Soon they can't do anything but believe there's total corruption.

Both the conception and

the style of Shadows were indebted to the neo-realists. The

young actor went to the Thalia frequently in the fifties and was

deeply affected

by the work of Visconti, de Sica and Rossellini, which was just making

its way to the United States at that point. Cassavetes was also

familiar

with other New York-based independent film that preceded his own work.

Commentators who regard him as "the first independent" are only

displaying

their ignorance of the history of independent American film, which goes

back to the early 1950s. Cassavetes was personally fond of the

work of

Morris Engel, Lionel Rogosin and Shirley Clarke, which he had seen before

he began Shadows. He was particularly fond of Engel's The

Little Fugitive, Lovers and Lollipops and Weddings

and Babies,

and Rogosin's On the Bowery. (I would note that although Cassavetes

mentions Godard in the following statement from the mid-seventies, the

works of the French New Wave had not been released in the United States

at the time Shadows was begun.)

I adore the neo-realists for

their humaneness of vision. Zavattini is surely the greatest screenwriter

that ever lived. Particularly inspirational to me when I made Shadows

were La Terra Trema, I Vitelloni, Umberto D and Bellissima.

The neo-realist filmmakers were not afraid of reality; they looked it

straight in the face. I have always admired their courage and their willingness

to show us how we really are. It's the same with Godard, early Bergman,

Kurosawa and the second greatest director next to Capra, Carl Dreyer.

Shadows contains much of that neo-realistic influence.

As different as Citizen

Kane was stylistically from his own work, it was also a personal favorite.

Welles' example not only blazed a path for later independent filmmakers,

but his sassiness, iconoclasm and panache (and that of the title character

in Kane) inspired Cassavetes, who had similar personal qualities.

Welles was a big influence

on me. The proof it could be done. That way. He showed me it was possible.

I'd want to work with him. I don't care what the problems are, because

he's an exciting man.

Yet, at the same time, Cassavetes

knew that every director was ultimately alone with his vision.

I'd like to feel that people

have influenced me, but then when you get on the floor you realize you're

really alone and no one can influence your work. They can just open you

up and give you confidence that the aim for quality is really the greatest

power a director can have – if you're in quest of power. In a way, you

must be out for power. We wouldn't make films if we didn't think that

in some way we could speak for everyone.

I'm not part of anything. I

never joined anything. I could work anywhere. Some of the greatest pictures

I've ever seen came from the studio system. I have nothing against it

at all. I'm an individual. Intellectual bullshit doesn't interest me.

I'm only interested in working with people who like to work and find out

about something that they don't already know. If people want to work on

a project, they've got to work on a project that's theirs. It's not mine

and it's not theirs. It's only yours if you make it yours. With actors,

as well as technicians, the biggest problem is to get people who really

want to do the job and let them do it their own way. The labels come afterwards.

If your films have no chance of being shown anywhere, if you don't have

enough money, you show them in basements; then they're called underground

films. It doesn't really matter what you call them. When you make a film

you aren't part of a movement. You want to make a film, this film, a personal

and individual one, and you do, with the help of your friends.

***

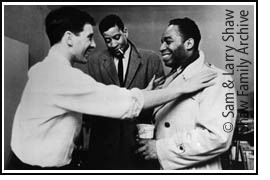

When

he spoke with interviewers a few years later, Cassavetes exaggerated

or outright lied about many

aspects of the production, bragging that he had shot the film in forty-two

days, that most of the footage was "grabbed" on the streets of New

York,

and that the movie was entirely spontaneous and improvised. In fact,

it would be two and a half years before the final film would be completed,

and even the initial period of shooting took more than ten weeks,

from

the end of February to the beginning of May 1957. Much of the final

version was scripted and all of it was carefully, meticulously planned.

Many of

the interiors were filmed on a stage in the Variety Arts building.

And many of the apparent exteriors were actually shot from inside

restaurants

or stores, looking out their plate-glass windows onto the street. Cassavetes

relied heavily on the advice of Robert Rossen. Rossen had pioneered

the

use of 16mm cameras and documentary footage in his studio work and

sat in on most of Shadows' early shooting, helping Cassavetes

in every way he could – teaching him how to light, load a

magazine and position a camera. But beyond Rossen's input, the film

was an amateur,

outlaw production

all the way. Although Cassavetes grossly exaggerated the number and

severity of run-ins with the police in subsequent accounts, there were

a few times

when New York's finest did interfere with the shoot. Cassavetes and

his merry band frequently had to run cables across a street or block

a walkway

with a tripod, and since they had no permits (because they couldn't

afford the required insurance), lookouts were posted so they could

pack up and

run for it when necessary. If they were caught by police they either

gave them a small bribe to look the other way or the shoot was moved

to a less

conspicuous location. (It was especially handy that one of the actors

was a part-time cab driver and would park his cab next to wherever

they

were shooting so that they could throw the camera into it and make

getaways.) The difficulty of the outdoor shooting is why, as much as

possible, it

was done at night, from indoors (e.g. through a restaurant window looking

out), from a concealed location (e.g. from a rooftop or movie theater

marquee) or with a telephoto lens (so that any attention the camera

and

crew attracted was relatively far from the performers – as

in the scene in which Tony and Lelia talk on the sidewalk in front

of his apartment). When

he spoke with interviewers a few years later, Cassavetes exaggerated

or outright lied about many

aspects of the production, bragging that he had shot the film in forty-two

days, that most of the footage was "grabbed" on the streets of New

York,

and that the movie was entirely spontaneous and improvised. In fact,

it would be two and a half years before the final film would be completed,

and even the initial period of shooting took more than ten weeks,

from

the end of February to the beginning of May 1957. Much of the final

version was scripted and all of it was carefully, meticulously planned.

Many of

the interiors were filmed on a stage in the Variety Arts building.

And many of the apparent exteriors were actually shot from inside

restaurants

or stores, looking out their plate-glass windows onto the street. Cassavetes

relied heavily on the advice of Robert Rossen. Rossen had pioneered

the

use of 16mm cameras and documentary footage in his studio work and

sat in on most of Shadows' early shooting, helping Cassavetes

in every way he could – teaching him how to light, load a

magazine and position a camera. But beyond Rossen's input, the film

was an amateur,

outlaw production

all the way. Although Cassavetes grossly exaggerated the number and

severity of run-ins with the police in subsequent accounts, there were

a few times

when New York's finest did interfere with the shoot. Cassavetes and

his merry band frequently had to run cables across a street or block

a walkway

with a tripod, and since they had no permits (because they couldn't

afford the required insurance), lookouts were posted so they could

pack up and

run for it when necessary. If they were caught by police they either

gave them a small bribe to look the other way or the shoot was moved

to a less

conspicuous location. (It was especially handy that one of the actors

was a part-time cab driver and would park his cab next to wherever

they

were shooting so that they could throw the camera into it and make

getaways.) The difficulty of the outdoor shooting is why, as much as

possible, it

was done at night, from indoors (e.g. through a restaurant window looking

out), from a concealed location (e.g. from a rooftop or movie theater

marquee) or with a telephoto lens (so that any attention the camera

and

crew attracted was relatively far from the performers – as

in the scene in which Tony and Lelia talk on the sidewalk in front

of his apartment).

***

Jean Shepherd had gathered

an enthusiastic following of eccentrics and free thinkers, whom

he referred

to as his "Night People". At Shepherd's behest, they performed a variety

of pranks and stunts throughout Manhattan – a forerunner

of what would later be called "guerrilla" or "street" theater. Some examples

of Shepherd's

merry mayhem: "Go to Marlboro Books tomorrow at ten and mill." "Tonight

at midnight, open your window and shout as loud as you can 'Screw

New York.'" "In the morning commute tomorrow, everybody give an

extra dime to the toll-taker for the person behind you." In the following

account,

Cassavetes acts like the plea for money was an accident, but he knew

exactly what he was doing and what the likely result would be when,

according

to a contemporary account, he began talking about how "if there can be

off-Broadway plays, why can't there be off-Broadway movies?"

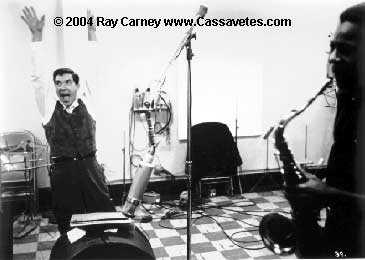

Shadows

from beginning to end was a creative accident. I was going on Jean Shepherd's

Night People radio show, because he had plugged Edge of the

City, and I wanted to thank him for it. I told Jean about the piece

we had done, and how it could be a good film. I said, "Wouldn't it

be terrific if [ordinary] people could make movies, instead of all these

Hollywood big-wigs who are only interested in business and how much the

picture was going to gross and everything?" And he asked if I thought

I'd be able to raise the money for it." If people really want to

see a movie about people," I answered, "they should just

contribute money." For a week afterwards, money came in. At the end

it totaled $2,500. And we were committed to start a film. One soldier

showed up with five dollars after hitchhiking 300 miles to give it to

us. And some really weird girl came in off the street; she had a mustache

and hair on her legs and the hair on her head was matted with dirt and

she wore a filthy polka-dot dress; she was really bad. After walking into

the workshop, this girl got down on her knees, grabbed my pants and said,

"I listened to your program last night. You are the Messiah."

Anyway, she became our sound editor and straightened out her life. In

fact, a lot of people who worked on the film were people who were screwed

up – and got straightened out working with the rest of us. We wouldn't

take anything bigger than a five dollar bill – though once, when

things looked real rough, we did cash a $100 check from Josh Logan. Shadows

from beginning to end was a creative accident. I was going on Jean Shepherd's

Night People radio show, because he had plugged Edge of the

City, and I wanted to thank him for it. I told Jean about the piece

we had done, and how it could be a good film. I said, "Wouldn't it

be terrific if [ordinary] people could make movies, instead of all these

Hollywood big-wigs who are only interested in business and how much the

picture was going to gross and everything?" And he asked if I thought

I'd be able to raise the money for it." If people really want to

see a movie about people," I answered, "they should just

contribute money." For a week afterwards, money came in. At the end

it totaled $2,500. And we were committed to start a film. One soldier

showed up with five dollars after hitchhiking 300 miles to give it to

us. And some really weird girl came in off the street; she had a mustache

and hair on her legs and the hair on her head was matted with dirt and

she wore a filthy polka-dot dress; she was really bad. After walking into

the workshop, this girl got down on her knees, grabbed my pants and said,

"I listened to your program last night. You are the Messiah."

Anyway, she became our sound editor and straightened out her life. In

fact, a lot of people who worked on the film were people who were screwed

up – and got straightened out working with the rest of us. We wouldn't

take anything bigger than a five dollar bill – though once, when

things looked real rough, we did cash a $100 check from Josh Logan.

* * *

Though it is easy to romanticize

it in hindsight, making the film presented enormous challenges.

When I started, I thought it would only take me a few months; it

took three years. I made every mistake known to man; I can't even remember

all the mistakes we made. I was so dumb! Having acted in movies, I kinda

knew how they were made, so after doing some shooting, I'd shout out

something

like "Print take three!" I'd neglected to hire a script girl, however,

so no one wrote down which take I wanted – with the astounding

result that all the film was printed. It was really the height of ignorance.

We did

everything wrong, technically. We began shooting without having the slightest

idea of what had to be done or what the film would be like. We had

no

idea at all. We didn't know a thing about technique: all we did was begin

shooting. The technical problems of the production were endless and

trying.

The "Sound Department" often looked at the recorder, only to

see no signal whatsoever! The only thing we did right was to get a group

of people together who were young, full of life and wanting to do something

of meaning.

There was [also] a struggle

because the actors had to find the confidence to have quiet at times,

and not just constantly talk. This took about the first three weeks of

the schedule. Eventually all this material was thrown away, and then everyone

became cool and easy and relaxed and they had their own things to say,

which was the point. Though I had to scrap most of what we shot

in the first eight weeks' shooting, later on, once they relaxed and gained

confidence, many of the things they did shocked even me, they were so

completely unpredictably true.

As often happens, many of

the so-called mistakes Cassavetes made were ultimately regarded as breakthroughs. As often happens, many of

the so-called mistakes Cassavetes made were ultimately regarded as breakthroughs.

The things we got praised for were the things we tried to cure. All

those things were accidents, not strokes of genius. We didn't have any

equipment, we didn't have a dolly. And we had all this movement, so we

used long lenses. And [we were] photographing in the street because

we

couldn't afford a studio or couldn't afford even to go inside some

place, you know. And our sound – when we opened Shadows in

England, they said, "The truest sound that we've ever seen." Well, at

that time,

almost all the pictures, certainly all the pictures at Twentieth Century

Fox, were looped. You know, all the sync that the actors actually spoke

on the stage was cleaned up and made to be absolutely sterile, so that

there was no sound behind anything. If you saw traffic, you wouldn't

hear

it. You'd just hear voices so that the dialogue would be clean. But we

recorded most of Shadows in a dance studio with Bob Fosse and

his group dancing above our heads, and we were shooting this movie.

So I never

considered the sound. We didn't even have enough money to print

it, to hear how bad it was. So when we came out, we had Sinatra singing

upstairs, and all kinds of boom, dancing feet above us. And that

was the sound of the picture. So we spent hours, days, weeks,

months,

years trying to straighten out this sound. Finally, it was impossible

and we just went with it. Well, when the picture opened in London they

said, "This is an innovation!" You know? Innovation! We killed ourselves

to try to ruin that innovation!

The lack of a script continuity

person created problems after the shooting was complete.

When it was finished, we didn't have enough money to print [all]

the sound. There was no dialogue [written down] so every take was different.

So we looked at it and said, "What the hell are we going to print here?

I don't know what they're saying. It looks terrific, everything's all

right, it's beautiful – we'll lay in the lines." So we had a couple

of secretaries who used to come up all the time and do transcripts for

us.

They volunteered their services, they had nothing to do, we had all silent

film. So we went to the deaf-mute place and we got lip-readers. They

read

everything and it took us about a year.

The

style was not chosen but forced on him. The

style was not chosen but forced on him.

We used a 16mm camera, partly because it was cheaper and partly because

we could do more hand-held stuff with it, and it was easier to handle

in the streets. We used a [Nagra] tape-recorder and a hand-held boom.

We rarely had rehearsals for the camera, even though Erich Kollmar, the

cameraman, likes rehearsals. I encouraged him to get it the first time,

as it happened. Erich found that the lighting and photographing of these

actors, who moved according to impulse instead of direction, prevented

him from using a camera in a conventional way. He was forced to photograph

the film with simplicity. He was driven to lighting a general area and

then hoping for the best. So we not only improvised in terms of the words,

but we improvised in terms of motions. The cameraman also improvised,

he had to follow the artists and light generally, so that the actor could

move when and wherever he pleased. The first week of shooting was just

about useless. We were all getting used to each other and to the equipment,

but it was not because of the camera movement that we had to throw footage

out. In fact, when you try it, you find that natural movement is easier

to follow than rehearsed movement, since it has a natural rhythm. A strange

and interesting thing happened in that the camera, in following the people,

followed them smoothly and beautifully, simply because people have a natural

rhythm. Whereas when they rehearse something according to a technical

mark, they begin to be jerky and unnatural, and no matter how talented

they are, the camera has a difficult time following them.

I think the important contribution

that Shadows can make to the film is that audiences go to the

cinema to see people: they only empathize with people, and not with

technical

virtuosity. Most people don't know what a "cut," or a "dissolve" or a

"fade-out" is, and I'm sure they are not concerned with them. And

what

we in the business might consider a brilliant shot doesn't really interest

them, because they are watching the people, and I think it becomes

important

for the artist to realize that the only important thing is a good actor.

Cassavetes always believed

that working with a tiny crew was an advantage.

Normally to shoot somewhere like Broadway there would be ten or a

dozen gaffers [lighting men], then another five or six grips [technicians]

to move the cameras and cables, and then all the producers and directors

on top of that. They wouldn't want anything [out of focus]; everything

would have to be clear cut. In a [Hollywood] picture you have marks to

hit, and the lighting cameraman always lights for you at a certain mark.

The actor is expected to go through a dramatic scene, staying within a

certain region where the lights are. If he gets out of light just half

an inch, then they'll cut the take and do it over again. So then the actor

begins to think about the light rather than about the person he is supposed

to be making love to, or arguing with.

One of Cassavetes' greatest

strengths was his ability to elicit performances that no other director

could get.

In

my own case I had worked in a lot of [commercial] films and I couldn't

adjust to the medium. I found that I wasn't as free as I could be on

the stage or in a live television show. So for me [making Shadows]

was mainly to find out why I was not free – because I didn't particularly

like to work in films, and yet I like the medium. The actor is the only

person in a film who works from emotion, in whom the emotional truth

of

a situation resides. If we had made Shadows in Hollywood, none

of the people could have emerged as the fine actors they are. It's probably

easier technically to make a film in Hollywood, but it would have been

difficult to be adventurous simply because there are certain rules and

regulations that are set specifically to destroy the actor and make him

feel uncomfortable – make the production so important that he

feels that

if he messes up just one line, that he is doing something terribly wrong

and may never work again. And this is especially true, not for the stars,

but with the feature players who might be stars later on, or with the

small players, the one-line players who might become feature players.

There's a certain cruelty in our business that is unbelievably bad. I

don't see how people can make pictures about people and then have absolutely

no regard for the people they are working with. In

my own case I had worked in a lot of [commercial] films and I couldn't

adjust to the medium. I found that I wasn't as free as I could be on

the stage or in a live television show. So for me [making Shadows]

was mainly to find out why I was not free – because I didn't particularly

like to work in films, and yet I like the medium. The actor is the only

person in a film who works from emotion, in whom the emotional truth

of

a situation resides. If we had made Shadows in Hollywood, none

of the people could have emerged as the fine actors they are. It's probably

easier technically to make a film in Hollywood, but it would have been

difficult to be adventurous simply because there are certain rules and

regulations that are set specifically to destroy the actor and make him

feel uncomfortable – make the production so important that he

feels that

if he messes up just one line, that he is doing something terribly wrong

and may never work again. And this is especially true, not for the stars,

but with the feature players who might be stars later on, or with the

small players, the one-line players who might become feature players.

There's a certain cruelty in our business that is unbelievably bad. I

don't see how people can make pictures about people and then have absolutely

no regard for the people they are working with.

* * *

Over the long period of

time that Shadows took to make, the thrill subsided.

In the course of [the filming,] the tide of outside enthusiasm dwindled

and finally turned into rejection. The Shadows people continued,

no longer with the hope of injecting the industry with vitality, but only

for the sake of their pride in themselves and in the film that they were

all devoted to. [On] the last day of shooting, I couldn't turn on the

camera. I was so fed up with doing it because there was no love of the

craft or the idea or anything. We're doing this experiment, and now it's

the last day, nobody's here except McEndree and me. He couldn't turn on

the camera and I couldn't turn on the camera and Ben was standing there

asking, "Are you going to roll this thing or not?" We're just

standing there looking at each other. We couldn't turn on this camera

because it had been such a hassle.

There also were squabbles

with actors over particular scenes. There also were squabbles

with actors over particular scenes.

The whole experience of getting people to do things was incredible.

There was a guy named David Pokitillow that we used a lot; one of the

people who hadn't acted before. He played the boyfriend and was a chess

player and a violinist. He did the first [party] scene and said, "Listen,

that's it." And as you know, that can't be it." You have got

to do this." He said, "No, I don't want to do this." So

he promised me he'd do a scene running through the park. He didn't show

up. We were standing out there in the park. I knew where he lived and

I ran over to his house with a couple of other guys." John, I'm with

a girl for Chrissake. I'm not an actor, God, I'm so fat and ugly and I

don't want to do this. I don't want to. I just hate it. I hate you."

So I said, "David, you have got to do it. If you do it, I swear to

God, I'll get you a chess set." I knew he loved chess." You

get the chess set. You come back with the chess set and then I'll do it."

So we ran out like a bunch of idiots, got the chess set, came back. He

says, "Put it by the door so I can see it." He opens the door

and he says, "OK, I'll do it." So we get down to the park. There's

a scene with Tony Ray and I said, "Hey, you run after him."

He said, "I'm not running for anybody." I said, "Please,

you can run 20 yards?" He said no. I said, "Please run 20 yards."

I'm reduced to nothing. And I'm standing there in the sunlight and the

cold and everything and Bennie says, "Jesus, man, I'd just deck him."

"David, what can I give you?" He said, "A Stradivarius."

"I can't give you a Stradivarius. You know I can't afford a Stradivarius,

but maybe we can rent it for you." So he ran 20 yards. He said, "That's

it." He went home.

Just shy of two years after

it was begun, Shadows was finally ready to be screened, in November

1958. The preview was not a success.

I went to a theater-owner friend of mine and I said, "Look, we want

to show our film and we can fill this theater." It was the Paris Theater

in New York and 600 people filled that theater and we turned away another

400 people at the door. About 15 minutes into the film the people started

to leave. And they left. And they left! And I began perspiring and the

cast was getting angry. We all sat closer and closer together and pretty

soon there wasn't anyone in the theater! I think there was one critic

in the theater, one critic who was a friend of ours, who walked over

to

us and said, "This is the most marvelous film I've ever seen in my life!"

And I said, "I don't want to hit you right now. I'm a little uptight,

not feeling too hot and none of us are, so" And he said, "No. This is

really a very good film." So, like all failures, you get a sense of

humor

about it and you go out and spend the night – when it's bad enough,

and this was so bad that it couldn't be repaired.

I could see the flaws in Shadows

myself: It was a totally intellectual film – and therefore less

than human. I had fallen in love with the camera, with technique, with

beautiful shots,

with experimentation for its own sake. All I did was exploiting film

technique, shooting rhythms, using large lenses – shooting through

trees, and windows.

It had a nice rhythm to it, but it had absolutely nothing to do with

people. Whereas you have to create interest in your characters because

this is

what audiences go to see. The film was filled with what you might call

"cinematic virtuosity" – for its own sake; with angles

and fancy cutting and a lot of jazz going on in the background. But the

one thing

that came at all alive to me after I had laid it aside a few weeks was

that just now and again the actors had survived all my tricks. But this

did not often happen! They barely came to life.

This

page only contains excerpts and selected passages from Ray Carney's writing

about John Cassavetes. To obtain the complete text as well as the complete

texts of many pieces about Cassavetes that are not included on the web

site, click

here. |