This

page describes Ray Carney's seventeen-year search for the long-lost

first version of Shadows and his almost unbelieveable luck

in finding the print.

To

read about how and why Cassavetes made two versions of the film,

go to the Shadows section of the "Films

of John Cassavetes Pages" or click

here and here for additional

information. You may then follow the other links in the top menu

on those pages to learn more about Shadows.

The

first version of Shadows is one of Ray Carney's most important

artistic finds, but Professor Carney has made a name for himself as the

discoverer and presenter of many other new works of art prior to this.

To read about a few of his other cinematic and literary finds, click

here.

To read about other unknown Cassavetes material (including recording studio master tapes and an unknown film by Cassavetes) Ray Carney has discovered, click here.

To read a 2008 interview with a New Zealand magazine where Ray Carney talks about Gena Rowlands's attempts to suppress or withhold Cassavetes' manuscripts and film prints from circulation, click here.

To

read a chronological listing of events between 1979 and the present connected

with Ray Carney's search for, discovery of, and presentation of new material

by or about John Cassavetes, including a chronological listing of the

attempts of Gena Rowlands's and Al Ruban's to deny or suppress Prof. Carney's

finds, click

here.

Click

here for best printing of text

Lost

and Found Department

Chasing Shadows

Ray Carney

At

the beginning of Citizen Kane the dying Charles Foster Kane whispers

the word “Rosebud,” and a reporter scurries about for a few

days and pieces together his life story from the two syllables. At

the beginning of Citizen Kane the dying Charles Foster Kane whispers

the word “Rosebud,” and a reporter scurries about for a few

days and pieces together his life story from the two syllables.

If only life were as simple

as the movies. In the late 1980s, a few years before John Cassavetes’ death,

I had a series of “Rosebud” conversations with him. The

American independent filmmaker told me things about his life and work

that he had never previously revealed. Our discussions covered a lot

of territory, but one of the things I spent the most time querying

him about was the fate of alternative versions of his films. Because

Cassavetes made most of his movies outside the studio system and financed

them himself (paid for from the salary he made acting in other directors’ films),

he was free from the constraints that limit Hollywood filmmakers. He

could take as long as he wanted to shoot his projects, spend as much

time as he needed to edit them, and if he was so inclined, re-shoot

or re-edit them as much as he wanted. In short, Cassavetes made films

the way poets write or painters paint. The result was that at various

points in their creation, most of his works–including Faces, Husbands, A

Woman Under the Influence, and The Killing of a Chinese Bookie–existed

in wildly differing versions, with different characters, different

scenes, and different running times.

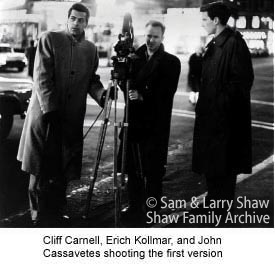

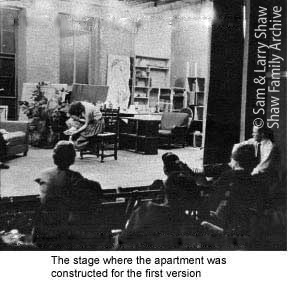

The film we spent the most

time talking about was Shadows. Cassavetes’ first feature,

generally regarded as the beginning of the American independent movement,

had had a vexed history. The filmmaker, in effect, made it twice, filming

an initial version in 1957 and screening it in the fall of 1958 at New

York’s Paris Theater for invited audiences. But, dissatisfied with

the response, Cassavetes re-shot much of the movie in early 1959, replacing

approximately half of the footage in the original print with newly created

material. In late 1959 the so-called “second version” of Shadows

premiered.

What

made the Shadows story especially interesting was that a number

of critics and viewers who saw both versions were convinced that Cassavetes

had made a grievous mistake. Jonas Mekas’s “Movie Journal”

column, published in The Village Voice on January 27, 1960, can

stand for all: What

made the Shadows story especially interesting was that a number

of critics and viewers who saw both versions were convinced that Cassavetes

had made a grievous mistake. Jonas Mekas’s “Movie Journal”

column, published in The Village Voice on January 27, 1960, can

stand for all:

“I have no further doubt

that whereas the second version of Shadows is just another

Hollywood film–however inspired, at moments–the first version

is the most frontier-breaking American feature film in at least a decade.

Rightly understood and properly presented, it could influence and change

the tone, subject matter, and style of the entire independent American

cinema.”

At the end of his piece, Mekas

expressed the hope that Cassavetes would come to his senses, withdraw

the second version and release the first

version; but it was not to be. Cassavetes did show the first version

several more times after he created the second version, but for unknown

reasons, the first version ceased to be available for screenings a

few years later. Despite the fact that Cassavetes made several public

statements that he was willing to screen and have people view the first

version, its last screenings took place in the early 1960s. It was

not shown again in his lifetime or following his death. For the forty-five

years that followed, the only version of Shadows anyone would ever see would be the re-shot,

re-edited version. The first version of the film assumed a legendary,

ghost-like status. Where was it? Why, given Cassavetes' avowed willingness

to have it screened, was it never shown again? Had it been lost or destroyed?

Did it still exist? Where was it? Did Cassavetes himself know?

When I asked Cassavetes the

whereabouts of the earlier print, he said he doubted it still existed.

The likelihood of its survival at the point was all the more remote

when one took into account the modesty of his filmmaking operations

in the late 1950s. The filmmaker told me that the first version of Shadows had

existed only as a single 16mm print. He had not had enough money to

make a duplicate or a backup, and the negative had been cut up to make

the second version.

The one small lead he offered

me was that he said he vaguely remembered donating the early print

to a film school. Jonas Mekas subsequently told me of a conversation

he had with Cassavetes in which the filmmaker was slightly more specific

and said that he had donated the print of the first version to "a

school in the Midwest."

Unfortunately for my peace

of mind, the damage had been done. I contacted every school in the

Midwest, starting with the alma mater of Cassavetes’ wife, Gena

Rowlands, the University of Wisconsin, which seemed a likely suspect.

To be sure I wasn’t failing to pursue any leads, I also tracked

down anyone I could locate who had been associated with the schools’ film

programs at the point the gift would have been made, presumably twenty-five

or thirty years earlier. I had many wonderful conversations, but came

up empty-handed.

Around the point Cassavetes

died, in 1989, I expanded the search. I contacted staff members at

every major American film archive, museum, and university film program

to see if the print had somehow been squirreled away in one of their

collections. After all, the title would have been the same for the

first and second versions; maybe they had the first version and didn’t

realize it. I began making announcements at film events I organized

or presided over. I asked friends–critics, filmmakers, and ordinary

people–to spread word of the quest. In the mid-1990s when I started

a web site, I posted a notice there. My friends joked that “shadowing Shadows” had

become a kind of madness.

There

was no shortage of tips and leads to pursue over the course of the

next decade. I communicated with hundreds of people in person, on the

telephone, and, subsequently, via e-mail. I tracked down people who

had been present at one of the early screenings. I recorded their accounts

of what had been in the first version. I talked to people who thought

they knew what had become of it. There were thrilling days when it

seemed that the print was within my grasp if only I could get in touch

with a particular person who knew someone who knew someone who knew

someone. But that final someone always eluded me. There were wild goose

chases where I flew into a strange city and met with a collector whom

I had been led to believe had the print in his possession. Needless

to say, each time the film turned out to be the second version. There

was no shortage of tips and leads to pursue over the course of the

next decade. I communicated with hundreds of people in person, on the

telephone, and, subsequently, via e-mail. I tracked down people who

had been present at one of the early screenings. I recorded their accounts

of what had been in the first version. I talked to people who thought

they knew what had become of it. There were thrilling days when it

seemed that the print was within my grasp if only I could get in touch

with a particular person who knew someone who knew someone who knew

someone. But that final someone always eluded me. There were wild goose

chases where I flew into a strange city and met with a collector whom

I had been led to believe had the print in his possession. Needless

to say, each time the film turned out to be the second version.

The comedy was not lost on

me–or my amused friends. So many of the accounts of what had

been in the early version–including Cassavetes’ own–contradicted

each other that I joked that the longer the search went on the less

I knew. Everything had been much clearer when I began. I teach literature

as well as film, and one day in a Henry James seminar I was leading

a discussion of “The Aspern Papers” and “The Figure

in the Carpet,” two comical stories about endless, pointless,

maniacal scholarly searches that never get anywhere, when I began laughing

so hard that I had to stop the discussion and explain to my students

that I had suddenly, shockingly recognized my own particular scholarly

madness in James’s characters. Was I really just crazy?

There were also comical tricks

of fate. For example, while searching for the Shadows print

in the Library of Congress collection, I stumbled across an uncatalogued,

unrecognized, long print of Faces. Very interesting, very

valuable; but, sorry, wrong movie. (Click

here to read more about my Faces discovery.)

I

can’t say I didn’t get discouraged. Sometime in the mid-1990s,

I put the search on the back burner and decided to take another tack.

If I could not actually find the physical print of the first version,

I would imaginatively reconstruct it by drawing on memories of the cast,

crew, and people who had seen it, as well as by studying the second version,

which included approximately thirty minutes of footage that had been in

the earlier print. I re-interviewed the cast and crew to pick their brains

for memories about the first version, then studied the composite second

version shot-by-shot for tell-tale clues about which footage had been

filmed in 1957 and which in 1959. It’s what scholars call using

“internal evidence” to study the revision of a work. I

can’t say I didn’t get discouraged. Sometime in the mid-1990s,

I put the search on the back burner and decided to take another tack.

If I could not actually find the physical print of the first version,

I would imaginatively reconstruct it by drawing on memories of the cast,

crew, and people who had seen it, as well as by studying the second version,

which included approximately thirty minutes of footage that had been in

the earlier print. I re-interviewed the cast and crew to pick their brains

for memories about the first version, then studied the composite second

version shot-by-shot for tell-tale clues about which footage had been

filmed in 1957 and which in 1959. It’s what scholars call using

“internal evidence” to study the revision of a work.

Almost all of that research

had to be done at actual movie theater screenings, since a video image

doesn’t reveal the kind of detail I required to draw my conclusions.

I pulled friends, dragging their feet and complaining, into 35mm screenings

in theaters, handed them clipboards, and we sat together in the front

row, whispering in each others’ ears and taking notes about how

an actor’s socks or the part in his hair changed in two successive

shots. We noted the length of the shadows on the ground to tell what

time of day scenes were filmed; and the size of the leaves and the

openness of buds on bushes in a park scene to decide the month. We

took notes about the models of the automobiles or the names of films

or plays visible on marquees in the background. That was only the raw

material, the data of the experiment; the fun of it was to connect

the dots, to reconstruct the entire first version out of such spider-web

tangles of interconnections. The title of a film on a marquee would

allow us to date an actress’s hairdo, which would then allow

us to date the scarf that an actor wore in another scene and … skipping

three or four more intervening steps … we could finally deduce

that another scene, different from any of the preceding ones, was definitely

filmed in March 1957 in the late afternoon of a day following a heavy

rain.

It took scores of screenings

and years of note-taking. Shadows was a gargantuan jig-saw

puzzle with thousands of missing pieces, but as I and my patient and

forbearing helpers put one tiny bit next to another tiny bit, large

chunks of the big picture of what had been filmed in the two different

periods of shooting emerged. It may not have been the most profound

scholarly work I’ve ever done, but it was certainly the most

fun–a little like playing Trivial Pursuit, doing the Times crossword,

and lining up the colors on a Rubik’s Cube at the same time.

The downs gave me the acrosses; the straight edges gave me the borders;

the posters gave me the socks and scarves and hairdos. Shadows became

my personal Dead Sea scrolls. Decoding the Rosetta stone or Linear

B must have felt like this. What larks.

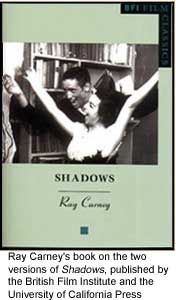

I

eventually published two books of conclusions: the first a monograph

about the film for the British Film Institute “Film Classics” series;

the second an augmented, revised version of the BFI book that I sell

on my web site. I’m embarrassed to admit that I continued going

to Shadows screenings and taking notes for more than a year

after the BFI book was published. I was in so deep I couldn’t

stop working on the changes just because my text had gone to the printer. I

eventually published two books of conclusions: the first a monograph

about the film for the British Film Institute “Film Classics” series;

the second an augmented, revised version of the BFI book that I sell

on my web site. I’m embarrassed to admit that I continued going

to Shadows screenings and taking notes for more than a year

after the BFI book was published. I was in so deep I couldn’t

stop working on the changes just because my text had gone to the printer.

Then one day two years ago,

some time after the BFI book appeared, one of the friends I had told

about the search called, saying he had run into a woman who might have

some information. When I finally tracked her down and got in touch

with her, it was your typical “good news-bad news” situation.

The good news was that she

confirmed that, yes, the title sounded familiar. Her father had been

a junk dealer who ran a second-hand shop in downtown Manhattan. One

of the ways he replenished his stock was by attending “lost and

found” sales held by the New York City Subway System. There were

so many forgotten umbrellas, mittens, eyeglasses, hats, pencils, pens,

and other things left on the trains that the Transit Authority annually

auctioned off the unclaimed items. Though a watch or nice piece of

jewelry might go for more, everything else generally went for ten to

twenty dollars per “lot”–a box which might contain

fifteen or twenty umbrellas, mittens, scarves, or hats. (Click

here to read a news story about a typical New York City Subway

Sale.) One year a long time ago (it was impossible to pin down the

date), there was a fiberboard film container in one of the boxes her

father bought. When he got home and opened up the carton he saw the

title Shadows (or at least that was what his daughter thought

she remembered him saying it was) scratched on the outer leader of

one of the reels, but since he had never heard of the movie, she told

me he simply put it aside and joked that he was disappointed it was

not a porno film.

In this case, the good news

was also the bad news. The subway was the wrong place to find the first

version. Not only didn’t it square with Cassavetes’ account

of what he had done with it, but it just didn’t seem a plausible

scenario. If the only print in the universe had been left on a subway

car, why hadn’t whoever lost it simply claimed it the next day?

The odds were also strongly against it being the right version. While

there had only been a single print of the first version, dozens of

prints of the later version had been struck and put in circulation

once Cassavetes became an established filmmaker. A print found on the

subway was far more likely to have been one of the many prints of the

second version that was couriered to or from a college film society

or art house booking in the 1960s or 1970s.

Even worse news was that all

of this had taken place something like thirty or forty years earlier.

In my very first conversation with her, the woman emphasized that even

assuming her memory of the title was correct, there was virtually no

chance the actual print still existed. The junk shop had gone out of

business long ago. The father had died years before. The members of

the family no longer lived in New York. The children had married and

had their own families and had moved away to other cities. The store's

contents had been sold off or thrown out years ago. Shadows was

just a distantly remembered word in a comical family story. The woman

put so little stock in the print’s survival that she didn’t

even really want to search for it when I asked her to. She told me

she had no idea where to look.

It

would take almost two years of polite pestering on my part before she

came up with anything; but I have to admit that even as I went through

the motions of talking to her every few weeks to remind her to ask other

family members if they had any idea if the print might have survived or

where it might be, I privately wrote off this lead as one more dead end

in a dead-end story. I resumed making announcements at Cassavetes events

and posting inquiries on my web site and elsewhere, but had virtually

no expectation of a positive outcome. I had given up. It

would take almost two years of polite pestering on my part before she

came up with anything; but I have to admit that even as I went through

the motions of talking to her every few weeks to remind her to ask other

family members if they had any idea if the print might have survived or

where it might be, I privately wrote off this lead as one more dead end

in a dead-end story. I resumed making announcements at Cassavetes events

and posting inquiries on my web site and elsewhere, but had virtually

no expectation of a positive outcome. I had given up.

That’s why when the

film was finally located in the attic of one of the children’s

houses in Florida, shipped to my home, and in my hands, I didn’t

even bother to look at it for a while. After the Fedex man dropped

it off, I peeked inside the carton and confirmed that Shadows was written

on the outer film leader; but after I had done that, I put the reels

back in the box, closed up the fiberboard container, and resumed doing

my university homework. I was convinced that the odds were absolutely

against it being the right print of the film. Indifference suddenly

turned to excitement and then to terror a few hours later when I manually

unspooled four or five feet of footage from the first reel and held

it up to my desk lamp. All I could make out was a figure walking down

a street, but that was enough. The second version of Shadows began

with a crowd scene.

In ten seconds I went from

being blasé to being afraid to touch the print for fear of leaving

marks on it. I have a projector in my house, but although it took some

self-restraint, I didn’t dare project it. If this actually were

the long-lost first version of Shadows, it would be just my luck

to have the projector shred or burn it. Even short of that sort of catastrophe,

introducing a few microscratches by passing the print through a projector

would be profoundly irresponsible. I might have spent 17 years and thirty

or forty thousand dollars of my own money finding it, but the print was

not really mine. It belonged to future generations. I owed them its preservation

in as perfect condition as possible.

With

a newly gingerly touch, I sealed up the carton and placed it carefully

on my coffee table. After a few days of phone calls and emails to preservation

experts, I made an appointment to have a high quality video copy created

at a professional film transfer house so that the original would never

have to be run through a projector. There was an inevitable delay of course.

It took me three or four days to find the right place with the right equipment

and I then had to wait for about a week for my appointment–ten days

of suddenly anxious sleep, fearful with the completely irrational fear

all collectors know, that my house would burn down in the interim, a week

of hefting the carton to reassure myself that the film was still in it,

before I was able to watch the movie from start to finish, and be sure

that the whole thing was not just some sort of mistake on my part. It

was the first version. It was an unprecedented and almost unbelievable

moment in film history. Cassavetes' oeuvre had had a new work added to

it. I had found a new first film by America's greatest filmmaker. Since

the released film of the same title was actually Cassavetes' second movie,

Cassavetes now had a new first film to his name. With

a newly gingerly touch, I sealed up the carton and placed it carefully

on my coffee table. After a few days of phone calls and emails to preservation

experts, I made an appointment to have a high quality video copy created

at a professional film transfer house so that the original would never

have to be run through a projector. There was an inevitable delay of course.

It took me three or four days to find the right place with the right equipment

and I then had to wait for about a week for my appointment–ten days

of suddenly anxious sleep, fearful with the completely irrational fear

all collectors know, that my house would burn down in the interim, a week

of hefting the carton to reassure myself that the film was still in it,

before I was able to watch the movie from start to finish, and be sure

that the whole thing was not just some sort of mistake on my part. It

was the first version. It was an unprecedented and almost unbelievable

moment in film history. Cassavetes' oeuvre had had a new work added to

it. I had found a new first film by America's greatest filmmaker. Since

the released film of the same title was actually Cassavetes' second movie,

Cassavetes now had a new first film to his name.

The print consisted of two

reels of 16mm black-and-white Kodak Safety Film with optical sound.

The first reel was 36 minutes long; the second 42 minutes, making a

total running time of 78 minutes. It exceeded my expectations in every

respect. It was not a rough assembly or work-in-progress, but a finished

work of art, complete in every detail, down to its innovative sound

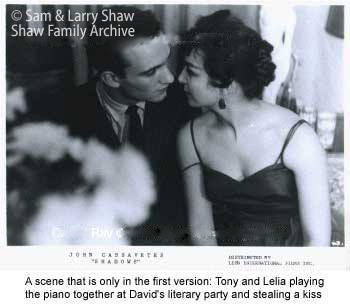

design and credits sequence. In terms of its content, there are more

than forty minutes of scenes that are not in the second version. The

discovery gives us a large chunk of new work by Cassavetes. It’s

a little like discovering five or ten early Picassos–if film

were taken as seriously as painting, that is.

Physically, although the celluloid

base was  shrunken and brittle from fifty years of storage, the emulsion

was in superb condition. Remember that, unlike the movies we see in

a movie theater, or the prints of the second version of Shadows that

I myself had seen, this print was not a duplicate or a blow-up, and

it had only been passed through a projector five or six times before

it was lost. In film terms, it was pristine, as sharp and clear as

a film can be. Not only was it custom printed directly from

the original negative that had passed through Cassavetes’ camera

in 1957, but it was virtually brand new, unworn and unscratched because

it had not been watched. In the scenes that the two versions share,

the image quality of the first version is, in fact, better even than

that of the recently restored UCLA print of the second version (which

is in fact of very little interest, since it contains no new material

and is not really different from the long-available release prints

of the standard second version). shrunken and brittle from fifty years of storage, the emulsion

was in superb condition. Remember that, unlike the movies we see in

a movie theater, or the prints of the second version of Shadows that

I myself had seen, this print was not a duplicate or a blow-up, and

it had only been passed through a projector five or six times before

it was lost. In film terms, it was pristine, as sharp and clear as

a film can be. Not only was it custom printed directly from

the original negative that had passed through Cassavetes’ camera

in 1957, but it was virtually brand new, unworn and unscratched because

it had not been watched. In the scenes that the two versions share,

the image quality of the first version is, in fact, better even than

that of the recently restored UCLA print of the second version (which

is in fact of very little interest, since it contains no new material

and is not really different from the long-available release prints

of the standard second version).

But can I reveal an embarrassing

secret? As wonderful as it was to find the first version, it was also

a letdown–not only because the excitement of the years of searching

were over, but because imaginatively reconstructing what had been in

the print was much more intellectually stimulating than simply viewing

it. Believe it or not, at moments I found myself feeling almost disappointed

I had found it.

One could ask whether the

discovery proves Jonas Mekas right; but that’s the wrong question.

It doesn’t really matter. The two versions of Shadows are

sufficiently different from each other, with different scenes, settings,

and emphases, that they deserve to be thought of as different films.

Each stands on its own as an independent work of art. (To view three brief video clips from the first version of Shadows, click here.)

The real value of the first

version is that it gives us an opportunity to go behind the scenes

into the workshop of the artist. Art historians X-ray Rembrandt’s

work to glimpse his changing intentions. Critics study the differences

between the quarto and folio versions of Shakespeare’s plays.

There is almost never an equivalent to these things in film. That is

the value of the first version of Shadows. It allows us to

eavesdrop on Cassavetes’ creative process–to, as it were,

stand behind him as he films and edits his first feature. We watch

him change his understanding of his film and his characters. His revisions

as he moves from one version to the next–the scenes he adds,

deletes, loops new dialogue into, adds music to, or moves to new positions

as he re-films and re-edits Shadows–allow an almost

unprecedented glimpse into the inner workings of the heart and mind

of one of the most important artists of the past fifty years.

The

odds against finding the print still astonish me–not only because

it was the only copy in the world and was in such an unexpected location,

but because of the timing. The junk-dealer’s children are themselves

now in their late fifties and sixties and the brown cardboard carton would

almost certainly have been thrown in the garbage when they died. (At least

one of the children has already died.) My friends used to joke me that

I was looking for a needle in a haystack, but after I found the print

I realized that the situation was even more dire than that metaphor suggested.

The haystack was not going to be there very much longer. If the print

had been in an archive or museum, it could have patiently sat there for

the next thousand years waiting for someone to discover it, but as a worthless

object gathering dust in the corner of an attic, it would not have survived

the next generation’s house clean-out. Though I had no idea that

the clock was ticking while I was engaged in my search, after I found

the print I realized that it had probably been the last chance to find

it for all eternity. The

odds against finding the print still astonish me–not only because

it was the only copy in the world and was in such an unexpected location,

but because of the timing. The junk-dealer’s children are themselves

now in their late fifties and sixties and the brown cardboard carton would

almost certainly have been thrown in the garbage when they died. (At least

one of the children has already died.) My friends used to joke me that

I was looking for a needle in a haystack, but after I found the print

I realized that the situation was even more dire than that metaphor suggested.

The haystack was not going to be there very much longer. If the print

had been in an archive or museum, it could have patiently sat there for

the next thousand years waiting for someone to discover it, but as a worthless

object gathering dust in the corner of an attic, it would not have survived

the next generation’s house clean-out. Though I had no idea that

the clock was ticking while I was engaged in my search, after I found

the print I realized that it had probably been the last chance to find

it for all eternity.

As to why it was left on the

subway, anybody’s guess is as good as mine. My own theory (based

on personal knowledge of some of the individuals involved with the

early screenings, though I dare not name names) is that one of the

people associated with the first version was carrying the carton back

from its final screening when an attractive blonde got on the train.

The rest I leave to your imagination. Thank goodness for blondes. And

junk collectors.

To

read Gena Rowlands’s response to Ray Carney’s Shadows discovery, click

here.

To

read about how and why Cassavetes made two versions of the film,

go to the Shadows section of the "Films of John Cassavetes

Pages" or click

here and here for

additional information. You may then follow the other links in

the top menu on those pages to learn more about Shadows.

The

first version of Shadows is one of Ray Carney's most important

artistic finds, but Professor Carney has made a name for himself as the

discoverer and presenter of many other new works of art prior to this.

To read about a few of his other cinematic and literary finds, click

here.

To read about other unknown Cassavetes material (including recording studio master tapes and an unknown film by Cassavetes) Ray Carney has discovered, click here.

To read a 2008 interview with a New Zealand magazine where Ray Carney talks about Gena Rowlands's attempts to suppress or withhold Cassavetes' manuscripts and film prints from circulation, click here.

To

read a chronological listing of events between 1979 and the present connected

with Ray Carney's search for, discovery of, and presentation of new material

by or about John Cassavetes, including a chronological listing of the

attempts of Gena Rowlands's and Al Ruban's to deny or suppress Prof. Carney's

finds, click

here. |