This

page describes Ray Carney's discovery of a new long print of Faces.

To read about Ray Carney's discovery of the long-lost first version

of Shadows, click

here.

The

first version of Shadows and the long version of Faces

are two of Ray Carney's most important artistic finds, but Professor Carney

has made a name for himself as the discoverer and presenter of many other

new and unknown works of art. To read about a few of his other cinematic

and literary finds, click

here.

To read about other unknown Cassavetes material (including recording studio master tapes and an unknown film by Cassavetes) Ray Carney has discovered, click here.

To

read a chronological listing of events between 1979 and the present connected

with Ray Carney's search for, discovery of, and presentation of new material

by or about John Cassavetes, including a chronological listing of the

attempts of Gena Rowlands's and Al Ruban's to deny or suppress Prof. Carney's

finds, click

here.

Click

here for best printing of text

December

10, 2001

PRESS RELEASE

For immediate release

Lost

and Found Department

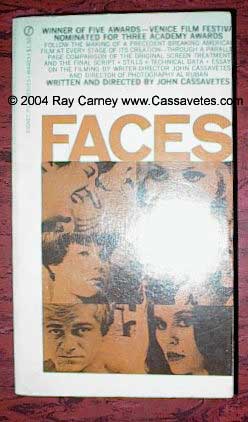

A Previously Unknown Version of John Cassavetes's Independent Masterwork Faces

Maverick

actor-writer-director John Cassavetes has been called the spiritual

father of American independent filmmaking. Because he made most

of his movies outside the studio system and financed them himself

(paid for with his salary as an actor in other directors' films),

he was free from the normal constraints that limit most American

filmmakers. He could make movies about anything he wanted. He

could take as long as he wanted to shoot them. And he could spend

as much time as he needed to edit them—changing his mind

as he went along. At least when it involved his non-studio work,

Cassavetes made films the way poets write or painters paint.

There were no commercial deadlines or bureaucratic compromises.

The film wasn't finished until he was finished with it. Maverick

actor-writer-director John Cassavetes has been called the spiritual

father of American independent filmmaking. Because he made most

of his movies outside the studio system and financed them himself

(paid for with his salary as an actor in other directors' films),

he was free from the normal constraints that limit most American

filmmakers. He could make movies about anything he wanted. He

could take as long as he wanted to shoot them. And he could spend

as much time as he needed to edit them—changing his mind

as he went along. At least when it involved his non-studio work,

Cassavetes made films the way poets write or painters paint.

There were no commercial deadlines or bureaucratic compromises.

The film wasn't finished until he was finished with it.

Cassavetes's home movie/feature

film, Faces, is a case in point. When it was released

in 1968, it was not only heralded as a turning point in the independent

movement—the first time a noncommercial movie had been embraced

by a mass American audience; but it was celebrated as one of

the major works of American film art. Renata Adler's pronouncement

in The New York Times can stand for all. She called Faces: "Far

and away the strongest, bluntest, most important American movie

of the year ... a motion picture so good one can hardly believe

it." Notwithstanding the non-Hollywood nature of the production, Faces went

on to garner three Academy Award nominations.

The

movie had been created in an entirely different way from a Hollywood

feature. It had been filmed in Cassavetes's home. The actors

had worked for nothing. Cassavetes had lavished six months on

the shooting process (as opposed to the six or eight weeks Hollywood

would have devoted to a comparable low-budget film), shooting

an unprecedented hundred and fifteen hours of footage. He had

then spent more than two years tinkering with the edit—in

the final six months, screening different assemblies to see how

audiences reacted to different edits. The

movie had been created in an entirely different way from a Hollywood

feature. It had been filmed in Cassavetes's home. The actors

had worked for nothing. Cassavetes had lavished six months on

the shooting process (as opposed to the six or eight weeks Hollywood

would have devoted to a comparable low-budget film), shooting

an unprecedented hundred and fifteen hours of footage. He had

then spent more than two years tinkering with the edit—in

the final six months, screening different assemblies to see how

audiences reacted to different edits.

Faces went through

five or six completely different assemblies, with different scenes,

different shot selections within scenes, different mood music,

and different running times for each version. For the past thirty-four

years, the conventional wisdom has been that Cassavetes destroyed

all of the alternative assemblies at the point he settled on

the final release print.

Enter Ray Carney, Professor

of Film and American Studies at Boston University, who is generally

regarded as the world's authority on Cassavetes's life and work.

He maintains a web site devoted to the filmmaker, and has published

many books on him. The most recent is the monumental 550-page Cassavetes

on Cassavetes, based on  conversations

with Cassavetes in the final decade of his life. Roger Ebert

praised it as "a labor of love, scholarship, and detective

work. From a chaotic mountain of primary and secondary sources,

Ray Carney has shaped the story of John Cassavetes' life and

work—using the words of the great director himself, and

also calling on his colleagues and friends to supply their memories

and revelations. 'This is the autobiography he never lived to

write,' Carney says, but it is more: Not only the life story,

but history, criticism, homage, lore. Like a Cassavetes film,

it bursts with life and humor, and then reveals fundamental truths." conversations

with Cassavetes in the final decade of his life. Roger Ebert

praised it as "a labor of love, scholarship, and detective

work. From a chaotic mountain of primary and secondary sources,

Ray Carney has shaped the story of John Cassavetes' life and

work—using the words of the great director himself, and

also calling on his colleagues and friends to supply their memories

and revelations. 'This is the autobiography he never lived to

write,' Carney says, but it is more: Not only the life story,

but history, criticism, homage, lore. Like a Cassavetes film,

it bursts with life and humor, and then reveals fundamental truths."

In late summer, Carney

was paging through the Library of Congress's on-line catalogue

and noticed an unexplained discrepancy. The Library owned several

prints of Faces, but one of  them

was catalogued as having the wrong length. Each of the entries

for the film should have read approximately the same length—around

11,600 feet (129 minutes); but one clocked in at 13,110 feet

(147 minutes). When Carney contacted staff members at the Motion

Picture Division of the Library of Congress, he was told it was

probably just a clerical error. But he said he felt in his bones

that it just might be one of the "lost" alternate edits

of the film. them

was catalogued as having the wrong length. Each of the entries

for the film should have read approximately the same length—around

11,600 feet (129 minutes); but one clocked in at 13,110 feet

(147 minutes). When Carney contacted staff members at the Motion

Picture Division of the Library of Congress, he was told it was

probably just a clerical error. But he said he felt in his bones

that it just might be one of the "lost" alternate edits

of the film.

"I was busy with

lectures and speaking engagements nearly every week of the fall;

but in late October and early November, after four days at the

Virginia Film Festival and a series of visiting lectures at Hollins

University, I squeezed in a side trip to the Library of Congress—to

see for myself. When I put the print on the Steenbeck, I realized

within seconds that I was not looking at a cataloguer's error."

Carney, who says he

knows the film shot-by-shot by heart, said the tip-off was not

only that the print began with a long credit crawl that is not

in the released version (which holds its credits until the end),

but that, even more interestingly, the credits in this print

included names of actors whose scenes are not in the release

print as well as titles of musical pieces not in the final film. "The

evidence from the credits alone was so conclusive, and I was

so excited, that I stopped the film before the first scene had

appeared on screen and told staff members what they had had sitting

in storage unknown to them for so many years, waiting to be discovered."

Carney

says that the print has many differences from the release version. "The

Library of Congress print has 18 minutes of entirely new footage

at the start—different scenes, characters, and events that

are not in the release print. That additional material accounts

for the longer running time. But the differences don't end there.

Each of the major scenes is presented in a slightly different

assembly from the release version, with slightly different shots

and different lines of dialogue at various points. The most striking

additional difference (beyond the different beginning scenes)

is in a long scene in the middle of the movie (the McCarthy and

Jeannie scene for those who know the film). Carney

says that the print has many differences from the release version. "The

Library of Congress print has 18 minutes of entirely new footage

at the start—different scenes, characters, and events that

are not in the release print. That additional material accounts

for the longer running time. But the differences don't end there.

Each of the major scenes is presented in a slightly different

assembly from the release version, with slightly different shots

and different lines of dialogue at various points. The most striking

additional difference (beyond the different beginning scenes)

is in a long scene in the middle of the movie (the McCarthy and

Jeannie scene for those who know the film).

"Since the Library

of Congress print is not in a rough or unfinished state, as the

presence of a finished credits sequence—one of the last

things to be added to a movie—indicates, it seems likely

that it represents one of Cassavetes's final versions; in fact,

it may have been intended to be the release version."

Carney summarizes the

artistic importance of the discovery: "Faces is one

of the seminal masterworks of American independent film. It is

to the American independent movement what The Passion of Joan

of Arc is to silent film or The Rules of the Game is

to French cinema. It's an historical landmark and a turning point.

The location of an alternate version is of clear historical importance.

But the discovery has a significance greater than an archeological

one. A comparison of the two versions of Faces provides

an opportunity to go behind-the-scenes into the workshop of the

artist.  We

can eavesdrop, as it were, on Cassavetes's creative process—watching

his mind at work as he experiments with different ways of telling

his story and with different stylistic effects, like the strange

use of music in the McCarthy scene. Cassavetes's revisions provide

a glimpse into the inner workings of the heart and mind of one

of the most important filmmakers of the past fifty years. It's

no exaggeration to compare this discovery to finding a version

of Citizen Kane with a new beginning and a different shot

selection." We

can eavesdrop, as it were, on Cassavetes's creative process—watching

his mind at work as he experiments with different ways of telling

his story and with different stylistic effects, like the strange

use of music in the McCarthy scene. Cassavetes's revisions provide

a glimpse into the inner workings of the heart and mind of one

of the most important filmmakers of the past fifty years. It's

no exaggeration to compare this discovery to finding a version

of Citizen Kane with a new beginning and a different shot

selection."

In one of those ironic

twists that occasionally take place in the search for lost masterpieces,

some time after his discovery of this new long print of Faces,

Prof. Carney realized that, in all likelihood, he had personally

been responsible for its being in the Library of Congress collection.

The story goes as follows. Several years before his visit to

the Library of Congress, Prof. Carney received a letter from

a company in charge of the liquidation of an old, discontinued

film warehouse. It informed him that rather than simply throwing

out old, unclaimed footage that had been left in storage, the

company was attempting to return the material to whoever they

could locate who might be interested in having it. Since Prof.

Carney was the acknowledged world's expert on John Cassavetes'

work, the company offered Prof. Carney the cans of Cassavetes

material that had been left in the warehouse. In this collection

of material were several cans labeled Faces. The liquidation

company offered Prof. Carney the opportunity to pick up the material

personally or have it shipped to a location of his choice. Since

he did not have storage or preservation facilities, Carney declined

the gift and instructed the company representative to get in

contact with the Motion Picture Division of the Library of Congress.

He told the company that the Library of Congress would be in

a better position to preserve and protect the material than he

was. Of course at that time, Prof. Carney did not realize that

he was turning down and passing along an alternate print of the

film. But based on what he has been able to learn about the acquisition

history of the print he viewed, the print described above, it

appears to have been the very material offered to him, the very

print he was personally responsible for turning over to the Library

of Congress, a few years before. The Gods must have been looking

out for him after that. It was poetic justice that Prof. Carney

would be the one to find the gift he had put in the hands of

the Library.

To read a press account

of the discovery click

here.

For more information

about the making of Faces and the alternate edits, see:

Ray

Carney, Cassavetes on Cassavetes: (Faber and Faber/Farrar, Straus

and Giroux, 2001), pp. 185-190 and 132-145.

To

read a chronological listing of events between 1979 and the present connected

with Ray Carney's search for, discovery of, and presentation of new material

by or about John Cassavetes, including a chronological listing of the

attempts of Gena Rowlands's and Al Ruban's to deny or suppress Prof. Carney's

finds, click

here.

The

opinion of Harmony Korine, writer-director of Kids, Gummo, Julian

Donkey-Boy about Ray Carney's Cassavetes on

Cassavetes:

"THE

BEST FILM BOOK EVER WRITTEN."

|

The

opinion of Xan Cassavetes, John Cassavetes' daughter

and the director of Z Channel and other works,

about Ray Carney's Cassavetes on Cassavetes,

as relayed to Carney by a friend in Los Angeles (stars

indicate omitted personal material):

"I

am still in LA, working on *** , which is coming along.

Real progress. This evening saw Z CHANNEL, a new

documentary by Xan Cassavetes. *** I spoke with her after

the screening. I thought you might like to know that

she absolutely loves CASS ON CASS. Says she sleeps

with it. Says it's enabled her to have conversations

with her father she never had."

|

To find out how to obtain

this book, click

here.

|