|

This

page contains statements by Ray Carney about the effect of Criterion

letting Gena Rowlands have veto power over what was included in the

box set. To read about Rowlands’s response to Prof. Carney’s

discovery of a long version of Cassavetes’ Faces in

2001, click

here.

To read about Rowlands’s response to Prof. Carney’s

discovery of the lost first version of Shadows in 2004, click

here.

Gena

Rowlands has waged a campaign devoted to savaging Prof. Carney's

reputation for telling the truth about John Cassavetes' life and

work.

She is terrified of the truth and interested in covering it up and

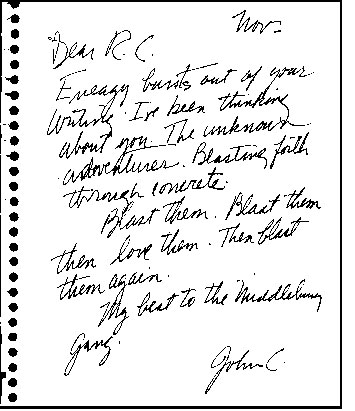

denying it. Click

here for

a glimpse of what Cassavetes was really like as a person and an illustration

of the kinds of facts that Rowlands

is retaliating against Carney for revealing. Her treatment of his Shadows and Faces finds,

and her insistence that Criterion remove his name from the Cassavetes

box set that he spent more than eight months helping

to create are part of her attempt to silence him.

The first interview

begins at the top of the page. To jump to the second interview, click

here. Another page of the site contains extended excerpts from other

interviews with Professor Carney that provide more information about Rowlands's

attempts to confiscate the print of Shadows and prevent it from

being screened. Click

here to go there. And this page contains a 2008 interview with a New Zealand magazine where Ray Carney talks about Rowlands's attempts to suppress or withhold other items, including Cassavetes' manuscripts and other film prints from circulation.

The first interview

begins immediately below this paragraph. To jump to the second interview,

click

here. Another page of the site contains extended excerpts from other

interviews with Professor Carney that provide more information about Rowlands's

attempts to confiscate the print of Shadows and prevent it from

being screened. Click here

to go there.

To

read a chronological listing of events between 1979 and the present connected

with Ray Carney's search for, discovery of, and presentation of new material

by or about John Cassavetes, including a chronological listing of the

attempts of Gena Rowlands's and Al Ruban's to deny or suppress Prof. Carney's

finds, click

here.

To read another

statement about why Gena Rowlands or anyone else who acted in Cassavetes'

films or someone who knew Cassavetes is not the ultimate authority on

the meaning of his work or on how it should be cared for or preserved,

click

here.

To read about

Carney's being blackballed by Rowlands from contributing to another DVD

project, and about Seymour Cassel's being put in his place and, at Rowlands's

behest, making (foolish and incorrect) comments that "there is no

first version of Shadows" in the voice-over commentary to

the Shadows disk, click

here.

Click

here for best printing of text

Prof.

Ray Carney worked for more than eight months and 300 hours as the official

scholarly advisor to Criterion for the Cassavetes DVD Box Set. To retaliate

for Prof. Carney's refusal to turn over to her the new version of Shadows

that he discovered and for his refusal to expunge things from his writing

and web site to conform with her wishes, Gena Rowlands told Criterion

to remove Prof. Carney's name and scholarly credit from the set as well

as specific parts of his work that she did not want included. Criterion

agreed.

In

Prof. Carney's view, giving the 74-year-old widow of a filmmaker a veto

over what can and cannot be written and said about him and his work has

extremely disturbing implications for the future of film scholarship.

Are academics and other serious critics merely to become lapdogs to Hollywood

movie stars, doing their bidding intellectually, clearing what is published

with them in advance, and being threatened with firing or legal action

against them if they don't?

Prof.

Carney discussed this ominous situation in an interview with George Hunka.

Gena Rowlands's continuing attempts to control what Carney writes and

to censor things in his work that she doesn't approve of are described

in more detail elsewhere in these pages. Click on the Rowlands items in

the top menu on this page to find out more.

Edited excerpts from an interview

with George Hunka

conducted for Reason Magazine

October 2004

ON YOUR RELATIONSHIP WITH CRITERION

How and when did Criterion first approach you about the DVD set? At

that point, you had apparently already had some conflict with Gena Rowlands

about the existence of the 1957 Shadows; was Criterion aware of this

when they approached you?

Criterion asked me to be the “scholarly advisor” for

the box set in October 2003. The original release date was planned

for around

April 2004, so most of my work was done in the late winter of 2003 and

early spring of 2004. But the date slipped first to the early summer

and then to the fall of 2004, as dates do in projects like this, and

I ended up continuing my work longer, finishing up most of it in late

March or early April. I was fired on May 8, if I remember correctly.

In other words, my work for

Criterion was more or less done when I was fired and had my name removed

and other promises reneged on. I’m

certain the timing was not a coincidence. Criterion got all of the work

out of me, and then announced that they were reneging on their agreement

with me to credit me.

Almost all of this occurred

prior to Rowlands’s blow-up with me over the finding of the

first version of Shadows. [Click

here to read about that.] I had begun working for Criterion in October

2003, didn’t find the film and definitively verify what it was until

late November and December, and Rowlands didn’t have me fired until

May. By that time I had put in more than eight months and three hundred

hours of work for Criterion. In fact, by May almost all my work on the

box set had already been completed.

No one can accuse me of being underhanded or deceitful. Criterion and

Rowlands were the underhanded ones. I was completely honest and honorable

in all of my dealings with Criterion. I kept them informed at every step

of the search and acquisition of Shadows. In fact, I told Criterion about

the search before I actually found the print, while I was still searching

for the film. I then told them about the find the day I found it. I kept

them informed while I was still checking out its authenticity, and I

gave them more information about it before I made a public announcement.

I kept nothing from them.

As to how did they feel about

including the first version of Shadows in the set—they were excited

about it. Peter Becker told me that it would be the most important

item in the release. He desperately wanted

to include it.

What

did Criterion ask you to provide, and what specifically was to be your

credit on the release? What

did Criterion ask you to provide, and what specifically was to be your

credit on the release?

It’s impossible to itemize everything I did in an interview. We’re

talking about eight months of work, almost every day. What I contributed

also changed as I went along. I’ve done many projects like this

and the scope of a project inevitably shifts and evolves as you work

on it. That’s a good thing. You get new ideas, you change your

mind, and you change your plans as you go along, as you find out what

you can and cannot get, what it costs, what the deadlines and realities

of including something are. Look, if I do say so myself, I’m the

world’s expert on this material. That was why Criterion made me

the scholarly advisor. I know more about Cassavetes’ work and what

is available than anyone alive. I provided a wealth of information about

dozens of things that could be included in the set, some of which were

used and others of which couldn’t be included for one reason or

another.

What was never in question

and never changed was that I was the “brains” behind

the box set. The producer knew only a little bit about Cassavetes and

depended on me to make recommendations on everything: what photos to

include, what documentary footage to include, which prints to use. (In

Cassavetes’ case, this is a particularly complex issue since there

are multiple versions of the different films.) And what other supplementary

material to bundle with the set. I was in charge of making recommendations

about everything. And I made scores of them, based on my twenty years

of experience and fresh research I did during that period of time— in

memos, in telephone conversations, by email, and in meetings in New York

and Boston.

I was the official scholarly

advisor for the set. That was my title. They confirmed it in writing

and re-confirmed it in dozens of emails,

telephone conversations, and face-to-face meetings. And Criterion

agreed to “pay me” by including extensive crediting of my

contribution, mentions of my publications, and links to my web site—among

other things. They reneged on all of that. None of it is included in

the set. When Gena told them to jump through her hoops, they only asked “how

high.” I was defrauded to please a 75-year-old widow.

On the set as released this month, what material did you provide them

with? What other material did you create exclusively for Criterion that

Criterion still retains? For example, for which films did you provide

commentary, how many stills did you provide, etc.

To tell you the truth, I still

haven’t seen the final released version of the set. Friends have

called and told me about it, but I don’t own it. Part of my arrangement

with Criterion was that for my eight months and hundreds of hours of work

I was to get a bunch of free sets in "partial payment," but

they reneged on that just as they reneged on everything else when Gena

told them to throw me overboard. So I’m be darned if I go into a

store and pay money to buy a copy at this point. I don’t want to

give them that satisfaction—or the sale! But Criterion told me that

they were not including the previously agreed upon scholarly advisor credit,

the web site link, the list of publications, and more or less everything

else. Of course they included my research, my suggestions on what to include

in the set, the list of people I gave them to talk to and interview. They

stole that material, just like Charles Kiselyak stole similar material

from me when he made the Constant Forge documentary that is included

in the box set. [Click

here to read about that project.] Welcome to the world of business.

Get someone to put hundreds of hours into something and then defraud him

of credit for it.

What was Criterion's reaction when you suggested the inclusion of the

1957 Shadows and the longer cut of Faces? Were these originally planned

for inclusion and later dropped?

They were enthusiastic. I

was too. They planned to include both films. They would have made superb

additions to the set. Not merely in a commercial

sense, though of course it would have helped the sales—but intellectually.

As if you included sketches from an artist’s notebooks in a show

of his or her paintings. It would have added depth to the release. The second Gena Rowlands learned of their desire to include this material (and my willingness to provide the Shadows print for free), she fired off a fax to them telling them words to the effect that she would sue their pants off if they included anything from either earlier film. (Click here to read the text of a letter written by Al Ruban at Gena Rowlands's behest to the Criterion Collection to prevent the print of the first version of Shadows from being released on video followed by the response from Criterion. The fax formalized and followed up on a previous telephone call on the same subject, forbidding Criterion's use of the print I offered to provide.)

It

seems from your web site that your discussion of the 1957 Shadows

on the commentary track for that film, and Rowlands' objection to it,

was the straw that broke the camel's back in terms of your participation

in the set. Did Becker or anyone else from Criterion, such as Johanna

Schiller, explicitly tell you this was the reason for your firing, or

was the email from Becker all the explanation you got? It

seems from your web site that your discussion of the 1957 Shadows

on the commentary track for that film, and Rowlands' objection to it,

was the straw that broke the camel's back in terms of your participation

in the set. Did Becker or anyone else from Criterion, such as Johanna

Schiller, explicitly tell you this was the reason for your firing, or

was the email from Becker all the explanation you got?

The email from Becker was

all I got. That’s the way they treat

someone who has put in eight months of his life on a project. I was fired

in a five sentence email with no more explanation than that. Criterion

would not really communicate with me after that point. Their lawyers

probably told them not to discuss my firing. The story was the same with

Gena. I wrote her a couple times after that expressing my puzzlement

about what had happened and holding out an olive branch—apologizing

for anything I had done to offend her, offering to meet with her and

discuss the situation, etc.—but she didn’t even reply. Complete

silence.

As much as being puzzled about why I had been fired, I was disgusted with the sneaky, underhanded way

it was done. Criterion kept reassuring me right

up to the last minute that I was doing terrific work, even as they were

just counting the days until they fired me. The timing was what gave

it away. The firing was timed to occur almost immediately after my work

for them was more or less complete. In retrospect, it seems clear to

me Gena had probably told Criterion to fire me a month or two earlier,

and they had agreed at that point, but they had deliberately held off doing it until I finished up everything I was providing for the box set. When I thought

back on it later, I could remember all these last-minute phone

calls for information in the last six weeks or so. What was going on

was that Criterion was milking me for all of the work they could get

out of me before they canned me and removed my credit from the set. Then

and only then, once they got what they were after, Becker wrote his email

to me.

What do you think Rowlands objected to in the work you prepared? Biographical

interpretation? Aesthetic interpretation? The simple act of a more ambivalent

presentation of Cassavetes and his work?

I know the difference between

those things, but they would mean nothing to Rowlands. The answer is

that she wants to control the interpretation

of her husband’s films and censor the facts connected with the

history of them. She objects to anything that is not cleared with her

in advance. She is committed to a sanitized history. The truth is too

scary for her to face. So, in this case, I guess you could say she objects

to both my interpretations and to my facts.

As background, you have to

keep two things in mind: First, Rowlands wasn’t all that involved

in the making of the films. She acted in them, but in most cases that

meant that she simply showed up when

it was time for her scenes to be filmed and went home when she was done.

She was not involved in the scripting, the casting, the shooting or the

postproduction process.

Second, Rowlands isn’t an intellectual or of a critical bent.

She is an actress—a wonderful actress—but that is different

from being a critic. An actress is a highly specialized individual with

a highly specialized set of skills. It is not the same thing as being

an intellectual. Rowlands is not a thinker. Her mind is not analytic.

She has little knowledge of film history or criticism. She has no talent

in that direction and little interest. When it comes to understanding

the function of film criticism, she's pretty much an ignoramus. (If you’re

reading this, sorry to have to say it, Gena! But I have devoted my life

to telling the truth and I won’t lie to flatter you.) Rowlands's

idea of film criticism is a gushy puff piece in the New York or L.A.

Times.

That’s the limit of her understanding of the functions of criticism.

She’s not a deep thinker about art or aesthetics. And if you doubt

that, look at the movies she’s chosen to act in over the past two

decades. They’re garbage. Sentimental dross. (Again, sorry Gena,

but that’s the facts!) That shows what she knows about art. She

only acted in her husband’s films because he needed her to do it.

It wasn’t really her choice. And she doesn’t even like many

of them. She once told me she thought Marvin and Tige was his greatest

acting performance. If you’ve seen the movie, that will tell you

a lot about her taste in film.

But where does that leave

me? Since she wasn’t there for most

of them, it means that Rowlands doesn’t know most of the facts

connected with the making of the films; and since she doesn’t really

understand what film criticism or interpretation is about, it means that

she doesn’t understand what I have been doing for the past twenty

years. Now, I don’t mind that. There’s no reason she should

have to know those things or should have to appreciate sophisticated

acts of analysis. My mother is a great person, and she doesn’t

understand and is not interested in those things either. But the difference

is that my mother doesn’t try to edit my work and my editor doesn’t

let my mother edit it. Rowlands thinks she has the right to veto or censor

what I write or say. And, even worse, Becker let her exercise it on his

box set.

Is it clear what madness it

would be to let my mother or Gena edit my work? When Gena reads my

writing, it genuinely baffles her. And given

her genuine lack of knowledge about the making of the films, she objects

to it whenever I say anything that is at all innovative or new. And she

really objects if it reveals something she would like to keep under wraps.

But do we want to live in a world where the wife of an artist controls

what is written about him? Do we really want to dumb-down film

commentary in this way? How in the world can Criterion possibly justify

their actions on moral or intellectual grounds? Why aren’t critics

and viewers protesting what Criterion has done? Why aren’t people

protesting what Gena is doing? How can she appear in public without being

grilled about this?

Let me give you a couple examples

of how my writing confuses Gena: the second version of Shadows ends

with a statement “The film you have

just seen was an improvisation.” Well, when I say in my BFI book

or my Cassavetes on Cassavetes book that much of the film was scripted,

Gena thinks I am just plain wrong! Why, the film says it “was an

improvisation.” How can I say it wasn’t? I won’t go

into the reasons why I know it wasn’t—or the talk I had with

Cassavetes himself about this subject—but I hope you can see how

when someone in a Shadows post-screening question-and-answer

session tells Gena what I wrote, she thinks I am spreading falsehoods

or, worse yet, saying her husband lied about the film.

It

puts me in an impossible situation. I can’t change the facts to

conform to Gena’s imperfect understanding or memory of them, but

I get fired by Criterion if I present them accurately. In the case of

Shadows, Rowlands still denies not only that much of the second

version was scripted, but that there even was a first version at all.

I am not describing a definitional problem, some semantic hair-splitting

about my argument about what constitutes a “first version.”

No. Rowlands denies that the basic events ever happened. So when I write

about them, she goes through the roof. She’s a very strong-willed,

opinionated individual. And to make it worse, she’s being advised

by an Iago-like businessman named Al Ruban, who resents that he is not

the one people turn to for information about the films. Ruban feeds Rowlands

libel about errors in my work, and Rowlands, because of her own insecurity

and lack of knowledge, falls for them. It

puts me in an impossible situation. I can’t change the facts to

conform to Gena’s imperfect understanding or memory of them, but

I get fired by Criterion if I present them accurately. In the case of

Shadows, Rowlands still denies not only that much of the second

version was scripted, but that there even was a first version at all.

I am not describing a definitional problem, some semantic hair-splitting

about my argument about what constitutes a “first version.”

No. Rowlands denies that the basic events ever happened. So when I write

about them, she goes through the roof. She’s a very strong-willed,

opinionated individual. And to make it worse, she’s being advised

by an Iago-like businessman named Al Ruban, who resents that he is not

the one people turn to for information about the films. Ruban feeds Rowlands

libel about errors in my work, and Rowlands, because of her own insecurity

and lack of knowledge, falls for them.

Not to protract my reply,

but let me add one more dimension to this. Everything I’ve said about the facts goes double for the interpretations.

Ruban and Rowlands don’t think like critics or understand how criticism

comes to its conclusions or what it means. When I say something like “Love

Streams reveals Cassavetes’ state of discouragement at that point

in his life,” she is baffled how I draw that conclusion. How can

a film tell me about its writer/director’s emotional state? Did

Cassavetes tell me he was “discouraged?” Well if he didn’t

say those exact words to me, then I have no business writing something

like that. In her view I am just making it all up.

If you hold legal title to the work you created for Criterion, why haven't

you pursued further legal action?

I

do own it. It’s my work. It was stolen and used in violation

of their agreement with me, which clearly involved crediting me for its

creation. Some very high-priced intellectual property lawyers have

told me that. Much of what is in the box set is my intellectual property.

I have contemplated legal action, and I have even taken a few preliminary

steps in that direction, against both Criterion and Charles Kiselyak for

stealing my intellectual property in his film, [Click

here to read more about what Kiselyak did] but legal action is so

time-consuming and so emotionally draining, and is such a distraction

from my real work of teaching, writing, and lecturing that I haven’t

come to a final decision about what I will ultimately do or how much of

my life I want to devote to fighting this injustice. I

do own it. It’s my work. It was stolen and used in violation

of their agreement with me, which clearly involved crediting me for its

creation. Some very high-priced intellectual property lawyers have

told me that. Much of what is in the box set is my intellectual property.

I have contemplated legal action, and I have even taken a few preliminary

steps in that direction, against both Criterion and Charles Kiselyak for

stealing my intellectual property in his film, [Click

here to read more about what Kiselyak did] but legal action is so

time-consuming and so emotionally draining, and is such a distraction

from my real work of teaching, writing, and lecturing that I haven’t

come to a final decision about what I will ultimately do or how much of

my life I want to devote to fighting this injustice.

What I have put hours of my

life into is trying to explain all of this to Rowlands, trying to get

her to see my side of things, to convince her that I bear her no personal

malice, but am just doing my job as a critic, presenter, and celebrator

of her husband’s work. Trying to convince her that the fairy-tale

version of her husband’s life and work that she and Kiselyak are

promulgating is counter-productive and that a more complex, nuanced

view is what people want. But I’ve gotten nowhere with that. She’s

terrified of the truth coming out. She’s acted in a completely two-faced

manner. Completely immorally. Pretending to be defending her husband’s

work, while actually pursuing a completely different agenda. Everything

she has done to me has been done for one of two reasons: first, to retaliate

for my refusal to turn the first version of Shadows over to her

so she can destroy or suppress it; second, to retaliate for my scholarly

attempt to present the truth about Cassavetes’ life. Rowlands is

terrified of the truth and interested in covering it up and hiding it

from view. She hates me for puncturing the myth she is trying to perpetuate,

and that other writers are still falling for. [Click

here for information about what Cassavetes was really like as a person,

for an example of the kinds of facts that Rowlands is retaliating against

Carney for revealing.]

I’ve always believed that the essence of being a great actor was

being able to enter into someone else’s point of view, but Gena

has sure proved me wrong about this. She is completely incapable of seeing

anything but her own self-protective point of view. And she is

willing to try to destroy anyone who dares to disagree with her or get

in her way.

In the event you do recover this work from Criterion, what do you plan

to do with it? Offer it on your Web site? Have you given thought to Internet

distribution of the alternative cuts of Shadows and Faces, a la Syberberg's

Hitler? (Or does the quality of Internet technology, along with any other

unresolved legal issues, dissuade you from doing so?)

As far as my voice-over commentary goes, I don’t have it.

I tried to get it back but Criterion won’t give the tapes to me.

Like Gena, I guess they’d rather suppress something or deny it

exists, than share it with the world. Shortly after I was fired, back

in May, I phoned Criterion and then when they didn’t reply, I wrote

them emails asking for a copy of my audio commentary. The audio commentary

had been removed on Rowlands’s orders. At first I got no reply,

but when I persisted in inquiring, I finally got a one- or two-sentence

email from a producer saying that Criterion would not even consider returning

anything to me until after the set had appeared in the stores. At that

point, which would be in September, she said she would “revisit” the

request. I’m almost certain that was her word. I remember it because

it struck me as such a weasel word, committing her to absolutely nothing

even after the set came out. She would “revisit” the request!

Well, it’s now October and the set has been out for almost a month,

and I have still not received anything back. I don’t expect to.

But even if I do, I’m

not a businessman and I don’t really

have the time to sell material out of the trunk of my car—or on

my web site. And I don’t really have any interest in doing it.

I want to make clear that I am not going public about this to sell anything,

to make money. Anything I have done and am doing is simply an attempt

to raise awareness about what has happened so that this doesn’t

happen to another professor next year with some other filmmaker’s

widow. I see this as an academic freedom of inquiry and expression issue

rather than as being about who owns what or who can sell what. This is

about censorship. About how a scholar is trying to write and speak deeply

and

spiritually about art and is being prevented from doing it by the forces

of commercialism in our culture, and by the way institutions kow-tow

to movie stars. It’s about whether just because someone is rich,

powerful, or famous they can control what someone writes and says about

an artist.

Although

Cassavetes indicated several years before his death that he didn't want

the 1957 Shadows to be distributed, do you think that he would

have approved of its dissemination alongside the 1959 version? (Admittedly,

this is an entirely theoretical question, but given Cassavetes' fascination

with the process of living and the process of art-making, it is interesting

to entertain the possibility.) Although

Cassavetes indicated several years before his death that he didn't want

the 1957 Shadows to be distributed, do you think that he would

have approved of its dissemination alongside the 1959 version? (Admittedly,

this is an entirely theoretical question, but given Cassavetes' fascination

with the process of living and the process of art-making, it is interesting

to entertain the possibility.)

That’s news to me. Where

did you get the information that Cassavetes didn’t want the first

version of the film screened? Cassavetes was not opposed to

screenings of the first version of Shadows. He held screenings

of it during his lifetime. The main reason he didn’t continue to

show it after the early 1960s was that he had lost the only print in

existence. The one left on the subway. The print I found. He did not

attempt to destroy or suppress it. He told me that when I talked to him.

Cassavetes’ did not intend to prevent screenings of the

first version of Shadows. Sorry, but I really rankle at statements

like the one you’ve

made. Because you’re repeating what Rowlands asserts without checking

the facts. But Rowlands is wrong. That’s the sort of statement

that magazines like Sight and Sound or Time Out have printed,

and that are in circulation on the internet, but it’s wrong!

You really have to check your facts before you make this kind of statement.

I was basing this on comments that Cassavetes made contemporaneous to

the release of the 1959 version of Shadows; obviously, later in his life,

he had changed his mind.

I still am not aware of any

statement Cassavetes made indicating that he wanted the first version

to be suppressed or destroyed—the things

Rowlands has threatened to do, under the name of honoring his wishes.

Everything I know and everything Cassavetes told me goes against that.

Could you tell me the source of the Andre Labarthe quotation you cite

on your web site:

"Now, a lot of film buffs heard about the two versions of Shadows

so they said, 'We want to see the first version, which was the great

version of Shadows!' .... So we showed that first version of Shadows and they championed it. They thought it was great.... That other version

exists and ... is allowed to be shown at any time...." —John

Cassavetes in an interview with Andre Labarthe, when he was asked whether

he didn't want people to see the earlier version of Shadows or had suppressed

the print of it.

Knowing the source would help to support your summary of Cassavetes'

comments to you regarding his attitude to the 1957 Shadows.

Sure I'll give you the source.

And you know the joke? You'll scream when I explain it. The quote is

now included the Criterion set! So you

get it? The piece I am alluding to was a kind of "Trojan horse." But

of course it's also interesting in itself. But the fun was that it refuted

Criterion's and Rowlands's positions and would appear in the Box Set.

Here's the back story: Criterion's

producer knew very little about Cassavetes and I more or less worked

out the entire contents of the box set for

her, all of the material they eventually included, plus a lot they didn't

include. Unfortunately, some of the best stuff didn't make the cut thanks

to Al and Gena and Becker. Over a period of months I did hundreds of

hours of research and made dozens of recommendations for supplementary

material to be included with the disks. At one point, among many other

suggestions, I told her we should include the Cineastes de notre temps television interview (which I had one of the only copies of in America—and

which a few years before I had already suggested Kiselyak use in his

documentary) where Andre Labarthe interviews Cassavetes about Faces.

It's an interesting piece in itself, but one of the reasons I thought

it would be especially amusing to include it was because around 42 minutes

into it (at the point it switches from Faces 1965 pre-release to its

1968 post-release period, where John is sitting in a chair in his living

room with a sport coat and tie on), Cassavetes starts talking about why

he was unfairly charged with "suppressing" the first version

of Shadows. Labarthe asks John something to the effect of: "Why

did you suppress the first version of Shadows or withdraw it from circulation

and refuse to make it available to all the people who wanted to see it?" And

you can hear John's answer, the one I quote on the site. In the web site

quote, I untangled a bit of his loopy syntax; but you can check it out

on the Criterion disk and hear his answer for yourself. Cassavetes says

he didn't suppress the first version, and that it can be shown any time.

He says he prefers the second version, but has nothing against screenings

of the first.

Well, as Criterion's scholarly

advisor I thought it would be a great joke to have this on the release.

And Criterion took my advice and included

it, probably without ever listening to the piece carefully enough to

see that they were including something that refuted Rowlands's position:

First, that there was no “first version” of Shadows, and

second, that Cassavetes didn’t want it ever to be seen again. That's

what scholarly advisors are for—to know the material inside and out,

to make recommendations on what to include and what not to include, and

to make sure that important information gets onto the disks. That's what

I did.

Well, jumping Jesus on a pogo stick, as the kids say today. You devil

you!

Apart from what you include on your letters page, have you received

any indications of support from other critics or directors? Anything

for attribution?

I have heard from a number

of high-level actors and directors.

All privately express passionate support. They use words like “unfair,” “unjust,” and “scandalous” to

describe Rowlands’s actions. One or two have even said things like “she’s

definitely losing it” or “the old bird’s memory and

mind are failing.” But the second I hint that a letter or call

from them might make a difference, they tell me they don’t want

to get involved because they have too many friends in common. Hollywood

is a very small town, and they all stick together unfortunately.

In a similar vein, a senior

figure at a major university film archive who has a relationship with

her told me that he sympathized with my position

100 percent, but he “didn’t want to jeopardize his archive’s

relationship with her or the possibility that she would leave them money

or material when she died.” It was about money to him. Unfortunately

that’s the way the world works. Money talks and people are afraid

of making a movie star mad.

Martin Scorsese was even tangentially

involved at one point. I have a hilarious story about him. It throws

a lot of light on how the rich

and famous really function. What their priorities are. But I can’t

tell it to you. Maybe some other day….

ON THE BOX SET AS IT EXISTS:

As it stands, the Criterion set provides an alternative cut of Chinese

Bookie, the 17-minute alternative opening to Faces (from your Library

of Congress find), and the 1957 Shadows is mentioned in the booklet notes

to the film (though not the existence of a print of this version). Why

this material specifically, especially if the 1957 Shadows is arguably

a more important discovery than the alternative 1978 cut of Chinese

Bookie?

It’s all Gena would agree to allow in the set. And that was after

a lot of persuasion. A lot of pressure from both me and Criterion! In

short, the alternate version of The Killing of a Chinese Bookie and the

17-minutes of Faces wouldn’t be there if I hadn’t taken

a bullet to get them there. When I started the Criterion project Gena,

through Al Ruban, turned down both requests. After she had vetoed the

alternate print of Shadows, Peter Becker told her that there wasn’t

enough to justify the box set if she didn’t agree to allowing Criterion

to include at least parts of both films. Becker shared some of his thinking

about this in a phone call with me a few weeks before he fired me. He

told me by not having the first version of Shadows, he was afraid no

one would want the box set and that Gena’s refusal to allow it

had put him in a terrible position. He was afraid they were going to

lose money on the project. So my pressure and the blow-up with

Rowlands put pressure on her to give in on including at least a sample

from Faces and The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. That’s the only

reason she finally agreed to allow them into the box set. It was kind

of a payback to Becker for firing me. It’s all Gena would agree to allow in the set. And that was after

a lot of persuasion. A lot of pressure from both me and Criterion! In

short, the alternate version of The Killing of a Chinese Bookie and the

17-minutes of Faces wouldn’t be there if I hadn’t taken

a bullet to get them there. When I started the Criterion project Gena,

through Al Ruban, turned down both requests. After she had vetoed the

alternate print of Shadows, Peter Becker told her that there wasn’t

enough to justify the box set if she didn’t agree to allowing Criterion

to include at least parts of both films. Becker shared some of his thinking

about this in a phone call with me a few weeks before he fired me. He

told me by not having the first version of Shadows, he was afraid no

one would want the box set and that Gena’s refusal to allow it

had put him in a terrible position. He was afraid they were going to

lose money on the project. So my pressure and the blow-up with

Rowlands put pressure on her to give in on including at least a sample

from Faces and The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. That’s the only

reason she finally agreed to allow them into the box set. It was kind

of a payback to Becker for firing me.

Do you think this set would be attractive to Criterion at all had it

not been for your work on John Cassavetes since the 1980s?

That’s not for me to

say. Suffice it to say that at the point Cassavetes died, his work

almost died with him. In the twenty years I

have been writing and lecturing about him, I have turned tens of thousands

of viewers onto his work. I used to joke with friends that Gena ought

to have paid me a salary as his publicist for two decades. That sure

would have been more than the royalties my books brought in during that

period of time. The film festival lectures, panel discussions, and screenings

I arranged paid nothing.

BROADER, MORE IMPORTANT ISSUES

In Cassavetes on Cassavetes,

you note that "Gena Rowlands has lent

support to Columbia's cuts [of Husbands] by saying that she herself prefers

the cut print over the one her husband fought so long and hard to defend" (p.

256); this, and the suppression of the 1957 Shadows, indicates that we're

unlikely to see versions of these films that aren't approved by Rowlands

et al. Given that Cassavetes entrusted her, Ruban and Faces Distribution

with the rights to his films (if not specifically his legacy or the interpretations

of those films), what can be done to prevent their abuse of this legacy?

I don’t know the answer to that question. Personally I’m

hoping that my speaking out like this can either: a) encourage her to

reconsider her failure to preserve her husband’s legacy or b) encourage

others to take action to preserve it. There’s no money in any of

this for me. Anything I have posted on my web site is an appeal to the

world to save and protect the art. I’m doing it for John, and that’s

all I really want to do. That’s what I meant before by saying I

was taking a bullet to preserve and fight for Cassavetes’ work.

There’s nothing in it for me. But I’m doing it for him.

Does the behavior of Criterion

in relationship to you and your work cast a "chilling effect" over

the study of film and art in general? In what sense and in what manner

may current and future critics

and students change their practice to accommodate this effect?

It certainly can’t help things. Writing on film is already trashy

enough, already skewed by celebrity suck-up values and movie star

hagiolatry. When one of the premier DVD releasing companies in America

jumps through a movie star’s hoops to keep her happy, it can’t

help but make other writers more cautious what they publish or say. Frankly,

I can’t imagine anyone else other than my own dumb self being brave

or foolhardy enough to stand up to Rowlands in this kind of situation.

Most film writers would have been more than happy to do anything she

wanted, to cut their work to fit her prejudices, just to keep a movie

star happy.

THE DEVIL'S ADVOCATE

What is beyond dispute is that, legally, Cassavetes passed the rights

to his films and their distribution to his widow, and that she is well

within her rights to release and license them as she sees fit. Although

she seems to have overstepped her rights on occasion, for example by

asking you to remove material from your Web site, nonetheless your books

on Cassavetes are still in print, you do have total control over what

you post at ww.cassavetes.com, and you continue to screen the earlier

Shadows for your students. In this case, why should she feel obliged

to include your work on the DVD set if she disagrees with your conclusions

or your approach?

Those “facts” are

wrong. That is not “beyond dispute!” Gena does not own the

first version of Shadows. Cassavetes renounced any claim to own

it when it was made. It was owned by the actors. It was improvised by

them. They created the script and scenes. Not him. And when it was done,

they owned it. Not him. I’ve recently located contracts and documents

from the period that make this official. [Click

here to read more about this situation.]

And to focus on whether Rowlands

likes or dislikes my work is to miss the point. Is my goal as a scholar

to make a movie star like me? Is my

purpose to suck-up to fame and power? The question at stake is

whether Criterion, the self-appointed “do it right,” “no

compromise,” “idealist” video releasers, should give

a 74-year old widow the right to determine what goes into one of

its releases and veto power over what gets excluded from it. And I don’t

mean just particular films or versions. Don’t forget that Rowlands

insisted that Criterion exclude my voice-over commentary and not

include my writing in the booklet. This was deep, searching, intellectual

commentary. As I was recording my voice-over commentary everyone

present was telling me how wonderful and revealing it was, how it opened

up whole new ways of thinking about Cassavetes’ work. Well, where

is it now? Rowlands had it removed (without ever hearing it, I was told).

In fact, she has not heard it to this day as far as I can tell. She was

simply retaliating for my refusal to turn over the first version of Shadows to her. Would a film professor check with Hitchcock’s kids about

what should be said about the films in their classroom? Would a film

festival director disinvite a guest because Beatrice Welles didn’t

like what he or she had written about Citizen Kane? Do we want a world

where money and power and celebrity determine what scholars say and do?

But wait, I have a better

analogy. How about if Gena Rowlands learned that you were writing this

piece and objected to it because she was afraid

you were giving me a platform to defend my actions. Just because she

was Cassavetes’ widow, would you think that gives her the right

to call your editor and have him fire you? And if he did it, would you

say, “Oh, she owns the films, she’s a very important person,

I guess she’s entitled to control what appears about them? I can

understand the editor not wanting to alienate her or risk a law suit

from her.” If we give movie stars this kind of power to censor

and veto and control what appears about them or the films they appeared

in (and that was what Becker was doing), we might as well live in some

banana republic where a dictator can tell us what to think and speak

and write.

That analogy with your article

and your editor is not as far-fetched

as it may seem. Much of my “publication” as a professor involves

doing voice-over commentary, program notes, and advising for videotapes

and disks. I was engaged in publishing scholarly material about Cassavetes

and Rowlands had me removed from the project and my work censored.

Becker, through Criterion's

publicity office, has turned down my request for an interview, but

I will be contacting them again for reaction to

your responses.

I figured Becker would not talk to you. Guilty people always take the

Fifth! He has a lot to hide. Therefore he has to be careful to keep his

story straight. To keep the alibis knit together. I don't. That's why

I don't mind talking. I know what happened. I'm not ashamed of any of

my behavior. I behaved honorably and honesty and above board. He has

to be careful what he says.

If you do talk to him ask

him if I was indeed the scholarly advisor to the set (and I clearly

was, putting in more than eight months and

300 hours of work, way beyond simply doing a voice-over commentary

or preparing essays for the booklet). Then ask him why my name is not

credited on the box set as scholarly advisor?

Of course, the only real answer is he removed it to kiss-ass a movie

star. But I'd be curious what he would tell you was the morality of removing

my clearly agreed upon and earned credit as scholarly advisor.

There’s another person

you could ask a similar question to. Call the head of the Motion Picture

Division at the Library of Congress. Ask

him or her why the print of Faces I found has not been screened

yet or why they have not issued a statement to the press. When I was

down there

and discovered it and told the higher-ups about it, they were excited

about the discovery and promised me they would have a big statement to

the press and a major screening event involving the film as a result.

Ask them why it never happened?

Why no press release or press conference from the Library? Why no announcement?

Why no screening? Why has the long version of Faces I discovered

effectively been suppressed for three years? The answer is that Ruban

and Rowlands

told the Library of Congress not to announce or screen it. Ask the

Motion Picture Division if they always kow-tow to movie stars in this

way. I thought the Library served the interests of the people. That

it was devoted to

the scholarship, preservation, and presentation of its collection. Turns

out I was wrong. They exist to cater to the whims, to do the bidding

of movie stars.

It’s extremely disturbing

that a public institution like the Library of Congress would suppress

a major scholarly find in this way to please a movie star. The Library

of Congress is a public institution. Your and my taxes built the building

and pay the employee’s salaries. We live in a democracy where a

place like the Library of Congress is supposed to serve the ordinary person's

needs. And what do we find? They are as in hock to Hollywood celebrities

as the Academy Awards Ceremony. When Rowlands tells them not to announce

something, or not to screen it, or to shut down a professor who has discovered

it and not talk to him (for three years now they have refused even to

respond to my inquiries about this subject), they bow down to celebrity.

Is this what we want from our public institutions? The man in charge at

the time of the discovery was someone named Patrick Longhey. He’s

now at the Eastman House. Ask him. [Click

here to read more about the Library of Congress’s response to

Prof. Carney’s discovery of Faces.]

I've

spoken to Rowlands' publicist and am setting up a phone interview with

her for this week. I haven't mentioned your name yet, only that I'm doing

a feature story on the DVD set. Here's hoping she doesn't slam the phone

down before I can get the second syllable of "Carney" out of

my mouth. I've

spoken to Rowlands' publicist and am setting up a phone interview with

her for this week. I haven't mentioned your name yet, only that I'm doing

a feature story on the DVD set. Here's hoping she doesn't slam the phone

down before I can get the second syllable of "Carney" out of

my mouth.

What you'll hear from Rowlands

is undoubtedly what I heard: That she has no knowledge of the "first version" as a separate work

at all. She regards it as a rough print, a prelim. version of the final

(second) film. If you have read my Shadows book and my Cass

on Cass,

you'll see the mistake in her understanding. She's simply, totally, absolutely

wrong. It's not a judgment call, not a gray area. She's just mistaken.

But her stance has a superficial plausibility—if you don't know the

facts. So don't be taken in. The first version of Shadows was a film

unto itself. It was meant to be released. It was finished, complete,

final in every detail. But Rowlands doesn't know this and refuses to

accept it. It's a demonstration of how little she really knows about

the other films as well. She was an actress in some of them. She showed

up for a few hours, did her scenes and went home. She had little or nothing

to do with the making of them. But of course she doesn't know what she

doesn't know. That's the nature of not knowing. (And she has been mislead,

profoundly so, by Al Ruban, which compounds the problem.) Well, I thought

a little background might help you prepare….

Let me give you one more bit

of background in case you interview Rowlands. Her whole position is

that she is honoring JC's wishes by suppressing

the first version, and that I am betraying them. Becker's email to me,

which I have posted on my web site, has her exact wording. Well, the Labarthe

quote is one refutation of that, but I wanted to emphasize that Cassavetes'

statement in the interview is not mere verbiage or empty talk. It's a

little known fact, but a fact indeed that Cassavetes actually did conduct

screenings of the first version of Shadows even after he had finished

the second version. I have detailed information about regular, public,

commercial, theatrical screenings (in other words, real screenings, not

just events for friends and relatives) of the first version of Shadows that Cassavetes approved and conducted before the only print of the first

version was left on the subway. I have every detail of those events:

the advertising, the box office ticket sales records, the attendance

figures, and the rental payments to Cassavetes. I have the documentation

approving the screenings and naming the payment terms with signatures

on it. And Rowlands has information about these screenings also. Because

I myself sent it to her months ago, along with dozens of other bits of

information. But don't confuse her with the facts! She still denies there

was a "first version"–let alone that Cassavetes ever

allowed it to be screened for the public.

In summary, her position is

completely bogus. If we are going to play the rhetorical game that

she has begun, it would be fair to say that

she is ironically enough the one betraying her husband’s wishes.

Cassavetes said the first version could be shown. And he showed it. Now

Rowlands is frying me for doing what he himself endorsed and did.

A POSTSCRIPT ONE MONTH LATER (VIA EMAIL)

Carney: Did you manage to talk with Rowlands, Ruban, Becker, or any

of their representatives? I'd really like to know, in all sincerity and

innocence, how in the world they justified their actions ethically.

Hunka: I spoke to Rowlands,

who pretty much repeated her "It's

my party and I'll invite who I want to" mantra. Neither Becker nor

Criterion responded to several requests for interviews via a variety

of approaches.

Carney: Remember the old song “It’s My Party and I’ll

Cry If I Want To?” I guess if you’re a movie star, being

a party girl and throwing a temper tantrum to get your way is more or

less what life comes down to. There’s no awareness that anything

else matters—like truth-telling, besmirching someone’s

career, or suppressing an important work of art.

As far as Criterion goes, Becker’s

non-response speaks for itself. What could he say morally to justify

what he has done? Nothing. So much for Criterion’s reputation as

the “idealistic, non-commercial, uncompromising art film releaser.”

Their sucking up to a Hollywood star kind of blows that image. And, make

no mistake about, it probably goes on all the time. I’m just the

first one to go public with it.

A follow-up

email exchange between George Hunka and Ray Carney in June 2005:

George,

What ever

happened with the Reason piece? Was it published? Killed? Delayed?

Meanwhile,

Gena's mischief continues.

Curiously,

Ray

++++++++++

Dear Ray,

Sorry to say that the piece

was eventually killed (without payment to me, needless to say, but that's

the risk of working on spec, as you know). I'm trying to place the piece

elsewhere and will let you know if I have any

success.

I'm also sorry to hear that

the "mischief" (and that's putting it mildly) continues. Have

you received any of your materials from Criterion to date? Any further

movement on that score?

Best,

George

+++++++++

George,

Well it's been

nine months and believe it or not, Criterion never even sent me a set.

My work is on them--my choices, my suggestions are there--but my name

is missing. And I don't even have set to show for it. (At least your editor

didn't publish your work but remove your name and refuse to send you a

copy of the issue! That would be a rough parallel.) And they haven't returned

a scrap of the work they suppressed to me. For example: they have the

only copies in existence of the voice-over tapes I recorded and refuse

to return them. I guess it's a lesson. Principles are one thing in a Criterion

press release and something a tad different when it comes to Peter Becker's

personal and professional interactions, if keeping his commitments means

he might displease a movie star.

The larger

lesson is the shabbiness of American film and video reviewing. How if

your issues are not on the Entertainment Tonight radarscope, no one cares.

You're the only American journalist who has interviewed me about this

situation and tried to publish something about it. The only one who has

asked me a single question about what happened. (I don't count a couple

interviews I did with students or former students.) And I'm not just talking

about TV journalism or tabloid writing on film. Look at how Manohla Dargis

reviewed the set for the NY Times and (even though she had to have known

the back-story or not have done her homework) never said a peep about

what went on. What does that tell you? It tells me a lot.

But thanks

for your efforts! And you can quote me!

Best wishes,

Ray

A note from Ray Carney:

Someone wrote me after reading the above material

and said words to the effect of: "Since Peter Becker refuses to give

his side of what happened and is stonewalling interviewers, it's unfair

to question his motives. You can't question a person's motives when they

won't tell you what they are."

A reply follows:

Of course you can question

someone's motives when they refuse to explain them. In fact, it's precisely

when they refuse to explain them to you that their motives are most suspect!

If Peter Becker had a good, a moral, an intellectually defensible reason

for what he did, he would be delighted to tell the world. E.g. If I had

been "difficult" to work with as a scholarly advisor, if I had

not done what I said I did for Criterion, if I were making the whole thing

up, if I had quit the project and left work undone-- he would not be stonewalling

interviewers. He would return their calls in a nanosecond to gleefully

point these things out. It's the very fact that he is guilty of everything

I accuse him of that makes him clam up. He doesn't have a leg to stand

on and is afraid if he says anything I'll use it against him in a law

suit. That's why he's "stonewalling."

Dargis's New York Times

piece, which is alluded to above, is described in the following interview.

Excerpts

from another interview with Ray Carney about the distortions of celebrity

worship in film study and criticism: Specifically about Gena Rowlands's

manipulation of the Library of Congress to suppress the alternate version

of Faces, and the slanted, partial coverage of the Criterion

events in the New York Times.

Excerpts

from Another Interview with Ray Carney

about the Distortions of Celebrity Worship

in Film Study and Criticism

Printing

the Press Release

Someone

who opens The Times film section thinks they are reading news –

factually correct, objective, unbiased news stories – or, in the case

of an opinion piece, a frank, uncoerced, candid personal viewpoint, when

they are actually reading advertising. The only reason we don’t detect

how weird this is because so many of our values are already skewed in

the same way television and the newspapers are. Since that de-realized

Rappaportian third realm is where most of our lives are already lived,

we don’t really notice it when we encounter it in the media. Money, power,

celebrity, and gossip define so much of our culture that we can’t see

how crazy it is to let them define the news as well.

You want an example? Although I gave up reading The Times

movie coverage on a regular basis years ago, because of my interest

in John Cassavetes, a friend sent me a piece published about him in September

2004. It was written by Manohla Dargis, one of the paper’s lead film reporters.

It was a retrospective appreciation of Cassavetes’ work. Now, anyone reading

the article would assume two things: first, that it was motivated sheerly

out of respect for Cassavetes’ films and a desire to pay homage to them;

and, second, that it represented a more or less objective, noncommercial

treatment of the subject.

Well, since I happen to know this particular subject inside-out,

I can tell you categorically that neither thing was true. First, Dargis’s

article wasn’t a disinterested homage. It was part of the publicity campaign

for a Cassavetes DVD box set being issued that same month. It was prompted

by and based on a press release issued by the company promoting the set.

Second, the article was full of distortions and errors, of both omission

and commission, which systematically suppressed a series of embarrassing

facts connected with the decision-making process behind the set and what

it included. I happen to know that part of the story since I was personally

involved in it as the set’s scholarly advisor. It’s told on my Cassavetes.com

web site. There’s not a whisper of any of that in what Dargis wrote. The

controversy about the set’s content and creation was totally suppressed.

Now if that’s an example of the work of the person who holds

the most prestigious film reviewing job in America, whose copy is overseen

by the most highly-respected editors in all of journalism, and is published

in “the newspaper of record” – that the story she filed was part of a

PR campaign for a DVD release and that it was tailored to promote the

product by saying only favorable things about it and avoiding raising

embarrassing issues…. well, I’ll leave it to your imagination what goes

on at places like Premiere and Entertainment Tonight.

The film reviewers might as well be working for the studios

and DVD releasers. In fact many of them are. Roger Ebert often reviews

and promotes DVD disks which he has been involved with the production

of.

But the problem is larger than that one tiny piece of the pie.

Virtually everybody in the reviewing game is in bed with everybody on

the promotional side of things. The publicists invent phony behind-the-scenes

drama, feed the reviewers fictional celebrity gossip, and fly them out

to LA on all-expense-paid junkets to interview the stars – and a week

or two later the reviewers dutifully report the fictions in the forms

of articles, interviews, and reviews. PR becomes news. When the White

House tries to manipulate reporters this way, the Washington press corps at least puts up a token

struggle. But when the studios do this to the reviewers, the only complaints

they ever get are that the hotel rooms are not fancy enough or that the

plane tickets are not first class. No one writing about film for a major

publication dares to say how corrupt the whole system is for fear that

they will be expelled from the club and be denied the next big interview

or photo op with the next big nobody.

I heard Stanley Tucci talk about this a while ago. He was on a panel

discussing the problems that confront filmmakers who attempt to do artistic

work. Everyone else was blaming the studios, the budgets, the cost of

special effects, the distributors, the movie theaters. He said wait a

minute, the main reason our movies are so stupid is because our reviewers

are. He talked

about how bad reviewing in America is, how it panders to mass entertainment

notions, how it sucks up to movie stars, how every reviewer in America

reviews the same five Hollywood releases every week, how none of them

supports art. I almost fell off my chair. It was the first time I ever heard

anyone ever publicly cite reviewers as the problem. Most actors and directors

will say it in private, but they are afraid to say it in public for fear

of having Anthony Lane or David Denby retaliate in a review. Tucci’s

point was that we’re not going to have audiences for good films until

we have reviewers who write about good films. If you’re an indie, you

can get all the distribution you want, but if reviewers don’t review your

work and encourage people to see it, only you and your friends will be

in the theaters watching it.

But, if we’re playing Pin the Tail on the Donkey, we need to take

a good hard look at ourselves too. Just as is the case with political

leaders and hit television shows, we ultimately get the reviewers and

films we deserve. If people really cared about seeing great films, they’d

boo bad movies or storm out of them and ask for their money back or stop

mobbing celebrity events with Renee Zellweger and Ben Stiller. As long

as we keep shelling out money to see junk, junk is what we’re going to

get. That’s how capitalism and democracy work. Or don’t work. Look at

who’s in the White House. Democracy is in even worse shape than film reviewing!

[Laughs] I guess I shouldn’t be laughing. It’s not funny. Our culture

is very sick. In very serious trouble.

Distortions

of Democratic Values

Why do you think reviewers are not

more supportive of artistic work?

The

basic problem is our culture’s love affair with money

and power and publicity. The celebrity suck-up factor is the most

blatant manifestation of it, since celebrities represent all three realms. They are rich; they are powerful; and they are famous. Actors

and directors are the American royalty. Everyone wants to interview

them or write about them and is afraid to say anything negative for fear

of alienating them. When was the last time Terry Gross or Barbara Walters

or Charlie Rose laid into Tom Hanks or Steven Spielberg for the meretriciousness

of their work? Of course, the real problem is that Gross and Walters and

Rose don’t even see that their work is stupid, because they are so awed

by the fact that they are interviewing celebrities.

The flip side is that

if you make a work of art that doesn’t have a movie star in it and doesn’t

have a PR office promoting it – in other words, if it isn’t wildly popular

or on the way to being wildly popular, as works of art generally are not

– it won’t be valued by the culture. Blame it on democracy. We’re so deep

into a view of life as being measured in terms of success and popularity

that we’ve forgotten that art can’t be evaluated this way.

We have to remember how weird it is to do this. It’s really

crazy. Spiritual and moral values that mattered for thousands of years

have been replaced by commercial evaluations. Instead of writing articles

and having discussions about a work’s truth, its morality, its ability

to inspire us or make us think, reviewers and commentators focus on the

size of its budget, its box office revenues, its demographic. Questions

about what is right or wrong, good or bad have been replaced by discussions

of what’s “hot,” what had the biggest opening weekend, what is generating

the biggest “buzz.” It’s a PR view of life.

The emphasis on race, class, gender, and ideology in the classroom

is an expression of the same way of viewing experience as if it were measurable

and quantifiable. Moral questions about the degree of love and nobility

in a work give way to political calculations about whether it is “representative,”

“inclusive,” “ideologically correct,” or – God help us – “offensive,”

“objectionable,” or “insulting.” Sociology replaces philosophy.

This force field distorts every area of film appreciation and

study: the books that get published, the articles that get written, what

is taught in our universities, what is screened at events.

Can you say more about that?

There’s

too much to say! [Laughing] Neither of us will live long enough. Let me

start with film festivals. The very reason they exist supposedly is to

celebrate the art of film – in other words to offer an alternative

to the culture of popularity, PR, and hype; but instead they attempt to

play the same game as the rest of the culture, programming their event

schedules and ceremonies around celebrity appearances, movie star awards,

saturation press coverage, and big ticket sales – which means that if

a film doesn’t have a name director or actor attached to it, it gets relegated

to a Tuesday morning screening. What’s the reason for a film festival

to exist if it’s going to organize its opening and closing night events

around Academy Awards values and celebrity appearances by Julia Roberts

and George Clooney?

Even

the so-called indie festivals are corrupted by the same PR understanding

of life. I was reminded of this not too long ago. I got a note from a

programmer who said he was thinking about inviting Rob Nilsson as a guest

of honor. Present a retrospective of his work and give him some kind of

award. But the programmer wanted to check with me whether I thought Nilsson’s

films would be a hit with the audience. If they weren’t, he said he didn’t

want to go through with the invitation. I guess you could say I lost my

cool. I told him that Nilsson had been busting his chops on the fringes

for something like thirty years, bucking the system, financing films out

of his own pocket, losing money, risking everything, and it was insulting

and irrelevant to be grading him on whether or not his name or work would

draw big audiences. I told the programmer he should become a Hollywood

producer since he had mastered the Hollywood way of thinking. He replied

– and I’m sure he thought he was being extremely reasonable and that I

was the nut case – that he couldn’t possibly invite someone if his work

wouldn’t get favorable reviews from local reviewers and draw decent-sized

audiences. So that’s what it comes down to, even at a small, prestigious

festival nominally committed to indie film. The programmers make the same

commercial calculations as your local metroplex. If the know-nothing reviewer

for the local paper doesn’t like Rob Nilsson’s work, or hasn’t heard of

him, you don’t invite Rob Nilsson.

I

saw the same thing happen when I was on the advisory board of the Boston

Film Festival. I quit in disgust after about ten years of it. The most

important reviewer in the city at that point was a Hollywood-addled idiot

named Jay Carr. At that time he was the lead reviewer for the Boston

Globe, but he has since moved on to being a television film reviewer.

That’s what happens if you are stupid enough. Well, year after year, we

would sit around a table at meetings debating whether we should invite

so-and-so or program such-and-such based on our guesses about “whether

Jay would cover the event” or “what kind of review Jay would give it.”

His opinion affected every decision.

The second worst Boston film critic at the time was a guy named

David Brudnoy. He was just as stupid as Carr and just as addled by movie-star

celebrity suck-up values, but did less damage because he wrote for a less

important paper, something called The Tab. The festival took a

different tack with him. They appointed him to the advisory board and

let him have input into the decision-making process! [Laughs] Isn't that

clever? Isn't that sicko? Do I have to point the moral and adorn the tale

by telling you that, as it sailed between the critical Scylla of Carr

and the Charybdis of Brudnoy, the festival ended up giving an award to

a bimbo movie star year after year? Surprise, surprise. Capitalism triumphs

again.

Celebrity

Worship

But

festivals do have to support themselves through ticket sales.

Yes,

but economics are not what is driving these decisions. I am talking

about values and the effects of values are subtler and more insidious.

The world we have inside us is our real undoing. It’s much a more powerful

determiner of actions than the world outside. Economics may be the reason

these programmers give for their decisions, but they are not really forced

to do what they do by economic pressures. The worship of fame and celebrity

and money, the measurement of things in terms of buzz and ticket sales

and press coverage and favorable reviews is inside us – even if

we don’t realize it. That internal slavery is our undoing.

Think

about public institutions like libraries and museums. They don’t have

to support their operations through box office receipts, but they are

no different. They host the same movie-star awards ceremonies, the same

opening night galas, the same name directors and films as commercial film

festivals do. The awe of celebrities, the desire to please them and get

favorable write-ups in the newspaper goes so deep in our culture and is

so much part of the internal values of a programmer or curator, that there

is no difference if the organization is a commercial one or a non-profit.

It’s

not economics, it’s values. I had first-hand experience of that a few

years ago. I discovered a new version of one of John Cassavetes’ films

in the Library of Congress. It was a major find. The Motion Picture Division

archivists were excited. I made plans with them to issue an announcement,

hold a press conference, and conduct a screening. So far so good. Then

Cassavetes’ widow, Gena Rowlands, told the staff she was opposed to it.

As far as I can determine, it appears that she was afraid that if the

new version became known it would cut into rentals of the old version.

Well,

if I was under any illusion that the Library of Congress served the interest

of the public, and was above being manipulated by a celebrity, it ended

that day. Rowlands had no legal or moral control over what the Library

did with the print, but the Library of Congress curator instantly agreed

to her request that the discovery be suppressed. At the same time, probably

at her request, he refused to tell me what was going on. I kept waiting

for the announcement and screening we had planned. When I called or wrote

to ask why it wasn’t being scheduled, he wouldn’t reply.

When

I later learned what had taken place, at first I couldn’t believe it.

I thought it must have all been a miscommunication. I had thought the

Library of Congress existed strictly to further the scholarship and appreciation

of its collection. I had thought my tax dollars went to supporting an

institution devoted to making available the greatest and best works of

the past.

Now

I realize how naďve I was. Gena Rowlands told them to jump through her

hoops, and the only question they asked was how high. [Does a voice:]

“She’s a famous movie star, for gosh sake! What part of ‘yes, ma’am’ don’t

you understand?” Wealth, power, and celebrity set the agenda in those

hallowed halls just as much as they do everywhere else in American culture.

It has nothing to do with economics or money. In fact, in this particular

case, the Library of Congress forfeited the potential box office receipts

from the screening of the new film to keep a movie star happy. The administrators

at the Library of Congress are as in awe of celebrity as some small-town

journalist. For the record, I made that discovery three years ago. To

this day, no announcement has been issued and no screenings have been

held.

When

I started out, I used to imagine that scholarly publishing operated outside

the system of fad and hype. Well, that may be true in terms of philosophy

and mathematics and physics, but it’s sure not the case with film books.

What gets published by scholarly presses is dictated by the same forces

as what is promoted in the culture. If something is popular, if something

is newsworthy, if it appeals to a particular demographic – gays, African-Americans,

World War II veterans, holocaust survivors, or whatever – that’s what

gets published.

I learned

that early on when I sent out the manuscript of my first book. It was

about Cassavetes and was turned down everywhere, even though each editor

said the writing was fine. Each one told me the problem was that Cassavetes

didn’t have a following. I remember the exact words of one of them: “If

it were Woody Allen, it would be different. But it’s Cassavetes. He’s