|

Jim

McKay

In Print

Jim McKay

talks with Ray Carney about writing about John Cassavetes

Filmmaker

Magazine (Fall 2001) |

I have a confession to make. About seven

or eight years ago, I came upon a very early, bootleg copy of a

book of interviews and commentary called Cassavetes on Cassavetes.

It was about 100 pages long and was a Xerox of a Xerox of a Xerox,

but in its pages I found some of the most inspiring thoughts about

film, art and life that I'd ever read. It quickly became the most

important book on my shelf.

Confession number two is that the book meant

so much to me that I Xeroxed the Xerox and gave it out to fellow

believers a number of times. I didn't know if the book would ever

find a publisher, and, in the meantime, how could I keep this crucial

information (both practical and spiritual) from others?

In the end, I think it'll work out fine.

The book has finally been published and, at over 500 pages, is so

much more jam-packed with material I'm certain that everyone who

got the bootleg from me will run out and buy the official version.

Over the course of shooting two features

(Girls Town and Our Song) and producing half a dozen

others, Ray Carney's Cassavetes on Cassavetes (Faber and

Faber, Inc., $25, paperback, 544 pages) sat by my bedside like a

bible. Late at night, while obsessing over some concern about tomorrow's

shoot, or the next day's credit-card bill, or an upcoming meeting

with a distributor, I'd open up the book to a random page and read.

Just a passage or a page, it never took much. In those pages, I

found the strength, support and spirit to go on. Sound a bit over-dramatic?

Well, if you're a filmmaker or a film fan interested in cinema outside

the Hollywood system, pick up the book for yourself and start reading.

You'll see.

Over a period of a few weeks, I engaged

in an e-mail conversation with Carney, a professor of film at Boston

University who maintains a web site devoted to independent film

at www.Cassavetes.com. We talked about independent film and the

influence of John Cassavetes's work.

Jim McKay:

You have three new books out this month. Describe them, the viewing

guide and the Shadows book very briefly, and Cassavetes

on Cassavetes more at length.

Ray Carney:

One of the reasons there are so few film really good books about

real

indies (as opposed to media-promoted figures like Stone and Spielberg)

is because the film book business is not that different from

the

movie business. Book proposals are judged in terms of their “box-office

potential.” An indie writer has to overcome obstacles, adapt to

circumstances, take chances, and pay the price – in emotions

and dollars – just

like an indie filmmaker. The only difference is that there is a

heck of a lot less money at stake in the book biz! You might

think

academic presses would be less commercially driven than the trade

houses, but they are even worse – since every book has

to be approved by a committee of film professors, who are always

the last

to know

anything new about film and are complete fashion slaves to media-created

trends and fads. In a nutshell, getting anything into print

about

Cassavetes is a struggle.

Believe

it or not, the Shadows book was originally going to be about

Faces! I have tons of material on the making of Faces

– drafts of the stage play the film was based on that Cassavetes

gave me, hours of tape-recorded behind-the-scenes stories by cast

and crew members, and access to prints of the film with entirely

different scenes from the release version. I proposed a book on

it to the British Film Institute for their “Film Classics” series,

but the editor turned me down, saying it wasn't on their list of

masterworks. Believe

it or not, the Shadows book was originally going to be about

Faces! I have tons of material on the making of Faces

– drafts of the stage play the film was based on that Cassavetes

gave me, hours of tape-recorded behind-the-scenes stories by cast

and crew members, and access to prints of the film with entirely

different scenes from the release version. I proposed a book on

it to the British Film Institute for their “Film Classics” series,

but the editor turned me down, saying it wasn't on their list of

masterworks.

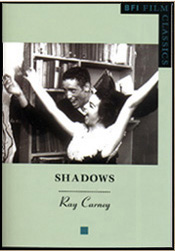

He counterproposed

a book on Shadows (which was on the list largely because

it plugged into the currently fashionable interest in jazz orchestration

and African-American characters). Fortunately, I had devoted years

to studying the film, and had just as much material about it, dating

back to a “Rosebud” conversation with Cassavetes shortly before

his death, where he told me that most of the important scenes in

his so-called “masterpiece of improvisation” were actually written

by a Hollywood screenwriter. You should have heard him laugh when

he said it. He had fooled the critics all those years! I had already

interviewed everyone involved in the production, so I used that

material to tell the real story of the making of one of the early

masterworks of the American independent movement.

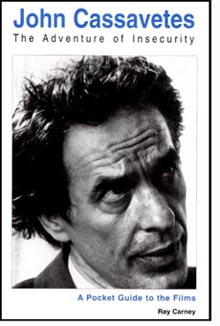

The

second book, John Cassavetes: The Adventure of Insecurity,

came out of the fact that I had always wanted to do a short, concise

overview of Cassavetes' life and work for general filmgoers –

a skinny paperback you could stuff in your pocket and take with

you to a festival that would give basic information and suggest

things to watch and notice. For more than ten years I had been writing

program notes about Cassavetes' work for film festivals and handing

them out as well as giving lectures and conducting question and

answer sessions following the screenings, and it just seemed like

common sense that I should gather some of that material together

and make it more conveniently available to viewers. (I was getting

tired of running around the country attending all those screenings.

And getting even more tired of running up to Kinko's between screenings

and paying my own money to make more copies of the essays when the

ones I had ran out and the festivals invariably told me their copy

machine was broken! I'll never forget one particularly frantic,

rainy night before a big screening at Anthology Film Archives!)

But when I approached various publishers, they all told me the same

thing – first, that they weren't sure that they would sell

enough copies; and second, that they only published books of a certain

minimum length and price. No dice on a viewer's guide. It was a

moment of truth for me. For years, I had been writing all these

essays praising indie filmmakers for putting their money where their

mouths were, and I was faced with the question of whether I was

brave enough to do the same thing. So a close friend and I pooled

our savings, got together ten thousand dollars, and published the

book on our own. That's why, at least as of right now, the only

way to get it is through Amazon or my web site. I'm living the indie

dream and nightmare. You self-finance it, you have to self-distribute it! The copies are sitting in boxes in my office. (Click here to read another statement about the financial realities of serious, scholarly research and publication.) The

second book, John Cassavetes: The Adventure of Insecurity,

came out of the fact that I had always wanted to do a short, concise

overview of Cassavetes' life and work for general filmgoers –

a skinny paperback you could stuff in your pocket and take with

you to a festival that would give basic information and suggest

things to watch and notice. For more than ten years I had been writing

program notes about Cassavetes' work for film festivals and handing

them out as well as giving lectures and conducting question and

answer sessions following the screenings, and it just seemed like

common sense that I should gather some of that material together

and make it more conveniently available to viewers. (I was getting

tired of running around the country attending all those screenings.

And getting even more tired of running up to Kinko's between screenings

and paying my own money to make more copies of the essays when the

ones I had ran out and the festivals invariably told me their copy

machine was broken! I'll never forget one particularly frantic,

rainy night before a big screening at Anthology Film Archives!)

But when I approached various publishers, they all told me the same

thing – first, that they weren't sure that they would sell

enough copies; and second, that they only published books of a certain

minimum length and price. No dice on a viewer's guide. It was a

moment of truth for me. For years, I had been writing all these

essays praising indie filmmakers for putting their money where their

mouths were, and I was faced with the question of whether I was

brave enough to do the same thing. So a close friend and I pooled

our savings, got together ten thousand dollars, and published the

book on our own. That's why, at least as of right now, the only

way to get it is through Amazon or my web site. I'm living the indie

dream and nightmare. You self-finance it, you have to self-distribute it! The copies are sitting in boxes in my office. (Click here to read another statement about the financial realities of serious, scholarly research and publication.)

The

third book, Cassavetes on Cassavetes, marks an era in my

life, something like ten or fifteen years of work. The origin was

a series of conversations I had with Cassavetes in the final decade

of his life. He said so many wonderful things that I thought it

would have been a shame to keep them to myself and not share them

with the world. The book is his own personal account of how he made

his movies – from the scripting, fund-raising, and planning,

to assembling the crew, struggling to get them into theaters, and

interacting with the press. I thought it was unbelievably great

stuff, but it too was a hard sell. I spent years trying to persuade

a publisher to print it. Oxford turned me down. Pantheon. Cambridge.

And a zillion others. Even Faber, who eventually published the book,

turned me down the first time I queried them – around 1992

or 1993. Most of them didn't even ask to see the manuscript before

they turned me down. In the early and mid-1990s Cassavetes was just

not a big enough name. I remember one editor saying, “Well, if it

were only Woody Allen or Oliver Stone, it would be different.” At

least she was honest. Meanwhile, years went by. I was almost at

the point of self-publishing it, when the same editor at Faber who

had turned me down the first time phoned me and asked if the text

was still available. Cassavetes had become more marketable in the

interim. Isn't it awful that that's what made the difference? Fashion. The

third book, Cassavetes on Cassavetes, marks an era in my

life, something like ten or fifteen years of work. The origin was

a series of conversations I had with Cassavetes in the final decade

of his life. He said so many wonderful things that I thought it

would have been a shame to keep them to myself and not share them

with the world. The book is his own personal account of how he made

his movies – from the scripting, fund-raising, and planning,

to assembling the crew, struggling to get them into theaters, and

interacting with the press. I thought it was unbelievably great

stuff, but it too was a hard sell. I spent years trying to persuade

a publisher to print it. Oxford turned me down. Pantheon. Cambridge.

And a zillion others. Even Faber, who eventually published the book,

turned me down the first time I queried them – around 1992

or 1993. Most of them didn't even ask to see the manuscript before

they turned me down. In the early and mid-1990s Cassavetes was just

not a big enough name. I remember one editor saying, “Well, if it

were only Woody Allen or Oliver Stone, it would be different.” At

least she was honest. Meanwhile, years went by. I was almost at

the point of self-publishing it, when the same editor at Faber who

had turned me down the first time phoned me and asked if the text

was still available. Cassavetes had become more marketable in the

interim. Isn't it awful that that's what made the difference? Fashion.

That was the

Cassavetes story in the United States. During his lifetime and

for

ten years after his death, he simply didn't exist as a filmmaker – not

for critics, not for viewers, not for reviewers. I am not exaggerating.

My American Dreaming: The Films of John Cassavetes and the American

Experience was published in 1984. It was the first book in

any language on his films and would remain the only book in English

until I published my second one with Cambridge: The Films of

John Cassavetes: Pragmatism, Modernism, and the Movies. It

was a very accessible, non-scholarly, and reasonably priced work.

And

you know how many copies it sold before it was put out of print

and shredded to make recycled paper? Eight hundred – six

hundred to libraries who have standing orders to buy every book

published

by

the University of California Press, which issued it, and two hundred

as regular bookstore or phone orders. Two hundred in ten years.

That was how many professors, film students, and ordinary people

in America were interested in reading about Cassavetes' life

and

work. I felt sorry for the press. They really took a bath on that

one.

Of course, things

were different in other countries. The French had to tell the Americans

that jazz was an art before America appreciated Louis Armstrong

and Charlie Parker, and that comedy could be serious, before they

could take Keaton and Chaplin seriously, and film is no exception.

An editor for a film book series in Paris simply heard about a very

early draft of my Cassavetes on Cassavetes manuscript and

issued an edition of a shortened version of it years ago, under

the title Autoportraits. But of course that's just another

form of fashion. In some countries he's popular, in others he's

not.

It was frustrating,

but now I realize that the delay was actually a great thing, because

every time the manuscript had been rejected, I had re-written it.

The longer I carried it around, the longer and better it got. So

Faber ended up publishing a much better book than I would have given

them ten years earlier. Even after they committed to the manuscript,

I couldn't resist rewriting it four or five more times. By that

point it had become much more than the personal story of Cassavetes'

life. It was an obsession. In the end it became an account of the

predicament of every independent artist trying to do something different,

something a little out of the mainstream. I realize now that it

became a veiled account of my own frustrations with the commercial

constraints expression.

* * *

McKay: Why

are Cassavetes' thoughts and principles important to both new and

experienced filmmakers in today's world of independent film?

Carney: Cassavetes

pioneered a new conception of what film can be and do. It was an

exploration of the meaning of his life and the lives of the people

around him. It was not about telling a hyped-up dramatic story or

taking the viewer on a rollercoaster ride, but of asking deep, probing

questions about the meaning of his experience, and asking viewers

to explore along with him. He made his movies the way poets write

or painters paint. Given everything Hollywood stands for, it's not

surprising that the films met with so much resistance from studio

heads, producers, distributors, reviewers, and audiences fighting

to hold onto their notion of movies as “story-telling” or “entertainment.”

Pauline Kael's response was typical. She jeered at his work in her

early reviews, then simply stopped reviewing it. As far as she was

concerned, it wasn't worth discussing.

I had the curator of a major film archive tell me that the next Cassavetes

would never be critically neglected the way Cassavetes had been.

“It could not happen again.... Critics and reviewers are so much

smarter and more perceptive now than they were in the sixties and

seventies.... Blah. Blah. Blah.” What a lot of hogwash. Nothing

has changed. The

next Cassavetes, the young artist trying to do challenging things

today, is in exactly the same situation he was.

The point is

that Cassavetes still has a lot to teach us. He was engaged in a battle for the soul of American film, but

it is not over. I wrote these three books for every young independent

writer, director, and actor – to show that he or she is not alone

and that self-expression is worth every ounce of the struggle to

celebrate and understand what we are.

This

page contains a short section from a longer interview Ray Carney

gave to filmmaker Jim McKay, which was excerpted in Filmmaker

magazine. In the selection above, Ray Carney discusses the real-world

work of getting a book proposal accepted by a publisher. The complete

interview covers many other topics. For more information about Ray

Carney's writing on independent film, including information about

obtaining the complete text of a series of interviews in which he

gives his views on criticism, film, teaching, and the life of a

writer, click here.

To read two more discussions of the realities of publishing, click

here and here. |