|

On writing: On writing:

A script is a series

of words strung together. They kind of spell out the story in a mysterious

way I deal with the characters as any writer would deal with a character.

There are certain characters that you like, that you have feeling for,

and other characters stand still. So you work until you have all the people

in some kind of motion.

When I first start writing

there's a sense of discovery. In some way it's not working, it's finding

some romance in the lives of people. You get fascinated with their lives.

If they stay with you then you want to do something – make it

into a movie,

put it on in some way. It was that which propelled us to keep on working

at it. Making a film is a mystery. If I knew anything about men and

women

to begin with, I wouldn't make it, because it would bore me. I really

feel that the script is written by what you can get out of it and

how much it means to you, and if it means nothing to you,

we start again and try to put ourselves up and communicate with

you. The idea of

taking a laborer and having him married to a wife who he can't capture,

is really exciting. I don't know how you work on that. So I write – I'll

do it any way [I can]. I'll hammer it out, I'll kick it out, I'll

beat

it to death, anyway you can get it. I don't think there are any rules.

The only rules are that you do the best you can. And when you're

not doing

the best you can, then you don't like yourself. And that's very individual

with everyone.

The preparations for the scripts

I've written are really long, hard, boring, intense studies. I don't just

enter into a film and say, "That's the film we're going to do."

I think, "Why make it?" For a long time. I think, "Well,

could the people be themselves, does this really happen to people, do

they really dream this, do they think this?" [There were] weeks of

wrestling to get the script right. I knew hard-hat workers like Nick,

and Gena knew women like Mabel, and although I wrote everything myself,

we would discuss lines and situations with Peter Falk, to get his opinion,

to see if he thought they were really true, really honest.

Letting the actors interpret

their parts

I

do a full and total screenplay and then the actors come to me and tell

me what they don't like. I listen to them. Then I try to get deeper into

the characters and find out what they want to play. In what they want

to play, somehow they're adding to the film. They're adding their own

sense of reality, and perceptions I wouldn't know from my relatively limited

point of view. It's a necessary part of the process for me. If for me

a line is right, I won't let the actors change it, but will allow them

latitude in interpretation. I

do a full and total screenplay and then the actors come to me and tell

me what they don't like. I listen to them. Then I try to get deeper into

the characters and find out what they want to play. In what they want

to play, somehow they're adding to the film. They're adding their own

sense of reality, and perceptions I wouldn't know from my relatively limited

point of view. It's a necessary part of the process for me. If for me

a line is right, I won't let the actors change it, but will allow them

latitude in interpretation.

I don't think audiences are

satisfied any longer with just touching the surface of people's lives;

I think they really want to get into a subject. Marriage, like any partnership,

is a rather difficult thing. And it has been taken rather lightly [in

the movies]. Family life is so different than what has been fed into us

through the tube and through radio and through the casual, inadvertent

greed that surrounds us. Films today show only a dream world and have

lost touch with the way people really are. For me it's the first real

family I've ever seen on screen. Idealized screen families generally don't

interest me because they have nothing to say to me about my own life.

Usually we put film in such simple terms while being endlessly involved

in talking about our personal experience. We admit how complex it is.

But it's as though we never look into a mirror and see what we are.

So the films I make really are trying to mirror that emotion, so we can

understand what our impulses are why we do things that get us into trouble,

when to worry about it, when to let them go. And maybe we can find something

in ourselves that is worthwhile.

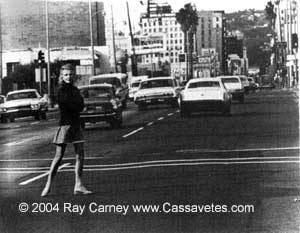

Location scouting

We

looked at maybe 150 houses in Los Angeles. It was really hard to find

something in the right price range that would make you feel you were in

a real house and also depict the kind of blue-collar existence we had

in mind. Some of the houses we scouted had plastic covers on everything,

plastic pictures on the walls, and most of the family's money went into

electrical appliances. That's a very real thing, but we didn't want it.

So we decided we needed a hand-me-down house and finally found one that

had been given to the Nick character and still had all the old furniture

and old woodwork. We decorated to correspond with the characters: sporting

trophies, photos of the children. Everyone brings their own ideas. For

instance, should the house be painted? We painted the front but not the

back, which could have been painted by some friends in exchange for a

couple of beers, but was left as it was. [We decided Nick] was too busy

worrying about his family. The actors [discussed] the clothes they will

be wearing, the influence of money on their lives, the lives of the children,

why they sleep on the ground floor, etc. Everything was discussed, nothing

came from me alone. We

looked at maybe 150 houses in Los Angeles. It was really hard to find

something in the right price range that would make you feel you were in

a real house and also depict the kind of blue-collar existence we had

in mind. Some of the houses we scouted had plastic covers on everything,

plastic pictures on the walls, and most of the family's money went into

electrical appliances. That's a very real thing, but we didn't want it.

So we decided we needed a hand-me-down house and finally found one that

had been given to the Nick character and still had all the old furniture

and old woodwork. We decorated to correspond with the characters: sporting

trophies, photos of the children. Everyone brings their own ideas. For

instance, should the house be painted? We painted the front but not the

back, which could have been painted by some friends in exchange for a

couple of beers, but was left as it was. [We decided Nick] was too busy

worrying about his family. The actors [discussed] the clothes they will

be wearing, the influence of money on their lives, the lives of the children,

why they sleep on the ground floor, etc. Everything was discussed, nothing

came from me alone.

The location could have been

a serious problem. At first everyone said, "How can you do a picture

where 80% of it happens in the same house?" I think that's one reason

why we had such difficulty financing the picture; it didn't seem to have

enough movement, enough openness. But we decided we wouldn't try to exploit

the house or make a "thing" of it. So most of it was shot in

the dining room and the foyer, basically from two angles. One good thing

about the house, of course, was that we could shoot all the sequences

there in continuity. [I] directed it in chronological sequence, just as

it would have been lived. I used long, long takes so that the actors could

develop emotional scenes without interruption.

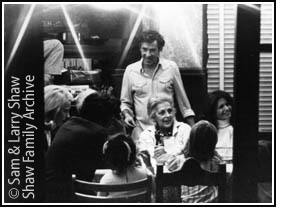

The shoot, which ran six

days a week for thirteen weeks, was Cassavetes' most emotionally demanding.

Making

the picture was tough. Once we began shooting, it was hell. The emotional

strain was so great that we never went out, socially, for thirteen weeks.

No movies, no parties, no home entertaining, nothing. At night we'd collapse,

make coffee, then start talking about the work. Yesterday's work, last

week's, last month's, next week's, next month's. We'd wake up in the night,

and talk some more. It was that kind of total commitment. Sometimes the

tension on the set was so great we could taste it. We'd quarrel, and somebody

would say, "No, that scene isn't true, it isn't honest, let's do

it again." We sat around the [Longhetti] house and again talked out

every scene until it seemed right, seemed right in this particular

environment. It was hard work. It was disciplined work. It wasn't

free-wheeling, you didn't feel like going out after the shooting. Every

time we make a movie it's always going to be fun and it never is. In the

ultimate finish of our relationship on that film it never is fun. It's

always, you look back on it with a great feeling of what a grueling adventure

that has been. Making

the picture was tough. Once we began shooting, it was hell. The emotional

strain was so great that we never went out, socially, for thirteen weeks.

No movies, no parties, no home entertaining, nothing. At night we'd collapse,

make coffee, then start talking about the work. Yesterday's work, last

week's, last month's, next week's, next month's. We'd wake up in the night,

and talk some more. It was that kind of total commitment. Sometimes the

tension on the set was so great we could taste it. We'd quarrel, and somebody

would say, "No, that scene isn't true, it isn't honest, let's do

it again." We sat around the [Longhetti] house and again talked out

every scene until it seemed right, seemed right in this particular

environment. It was hard work. It was disciplined work. It wasn't

free-wheeling, you didn't feel like going out after the shooting. Every

time we make a movie it's always going to be fun and it never is. In the

ultimate finish of our relationship on that film it never is fun. It's

always, you look back on it with a great feeling of what a grueling adventure

that has been.

* * *

[In]

directing you're really like a host, that everyone's going to your

party, and it's very difficult

for [the crew] to help you get glory. Once they trust that you really

are interested in the work, and not in your own perfection, they will

work very hard for you. The actors are the same. They don't want to

be

second fiddle to a camera. When people begin to feel a little upset,

there begin to be mysteries about filmmaking. There are no mysteries

to making

films. There is no mystery to writing. I try to make it comfortable

for the actor by realizing what they're doing is so personal. If you're

doing

a movie and somebody slaps a slate in front of you and everybody stands

around expecting you to be brilliant, then it's gonna be like a contest.

I like to develop an atmosphere where that doesn't exist; where nobody

is looking at you to see how good you are; where people can function.

It's very hard to let the technical processes of film take over and

then

expect the actors to reveal themselves. I mean, you can't take a shower

at a dinner party. You make a movie to tell what you know about life – about

your life. But after waiting around for eight hours, for set-ups, for

lights, all of it, when it comes time to shoot, you're thinking, 'I

don't

wanna tell you about my life anymore! Why should I tell you about

my life!' On a set there's really a lot that can hamper the actors.

For

example, in this film, here's maybe the most important moment in two

people's lives: a guy is committing his wife to a mental hospital.

[In other movies]

someone is also fiddling with your hair, putting lipstick on you, placing

lights above you, sitting you down, marking your feet, moving cameras,

yelling, "Hey, she doesn't look good; her skin is out of focus." Now,

I ask you, how can the actors concentrate? So we do all this before

the actors come on-stage. We all work quietly, and hopefully efficiently,

and get it done. [In]

directing you're really like a host, that everyone's going to your

party, and it's very difficult

for [the crew] to help you get glory. Once they trust that you really

are interested in the work, and not in your own perfection, they will

work very hard for you. The actors are the same. They don't want to

be

second fiddle to a camera. When people begin to feel a little upset,

there begin to be mysteries about filmmaking. There are no mysteries

to making

films. There is no mystery to writing. I try to make it comfortable

for the actor by realizing what they're doing is so personal. If you're

doing

a movie and somebody slaps a slate in front of you and everybody stands

around expecting you to be brilliant, then it's gonna be like a contest.

I like to develop an atmosphere where that doesn't exist; where nobody

is looking at you to see how good you are; where people can function.

It's very hard to let the technical processes of film take over and

then

expect the actors to reveal themselves. I mean, you can't take a shower

at a dinner party. You make a movie to tell what you know about life – about

your life. But after waiting around for eight hours, for set-ups, for

lights, all of it, when it comes time to shoot, you're thinking, 'I

don't

wanna tell you about my life anymore! Why should I tell you about

my life!' On a set there's really a lot that can hamper the actors.

For

example, in this film, here's maybe the most important moment in two

people's lives: a guy is committing his wife to a mental hospital.

[In other movies]

someone is also fiddling with your hair, putting lipstick on you, placing

lights above you, sitting you down, marking your feet, moving cameras,

yelling, "Hey, she doesn't look good; her skin is out of focus." Now,

I ask you, how can the actors concentrate? So we do all this before

the actors come on-stage. We all work quietly, and hopefully efficiently,

and get it done.

Rehearsals are tiresome, boring,

and the whole crew becomes a kind of audience. If the crew gets bored,

the actors feel that it's bad. That is why I want everything to go fast,

and used long focal lenses and a set that has some depth. What's important

to me is just that you convince the audience and yourself that what's

on the screen is really happening. [The crew doesn't need a rehearsal

because] they watch [all of the preparation]. In other words, everyone

always rehearses. They're rehearsing for hours. They're rehearsing or

walking around, doing the scene for hours. [The only way a crew member

wouldn't know what's going on is if] you're out playing cards, if you're

out talking, or making points with the producer, or Elaine May comes on

the set and you want to get her coffee. Then you'll blow the scene,

you know? If you really are interested, you have lots of time to know

what's happening.

The actor brings himself

to it

We deal with thoughts and emotions and I hope that the actors don't

feel that the material is scripted. So they don't think of the script.

Everything must find its inspiration in the moment at hand. The words

are there but two very good actors must want to express more of their

love than by just reading the script. Only in this way can they really

believe in their characters and express them. It really is a product

of

a group of people coming in and interpreting their roles. Really, truthfully

interpreting their roles. Everything that Gena did she did herself.

Everything

that

Peter did he did himself. Everything that all those other actors did,

they did themselves. I give a lot of house – if there's any credit

to be given it is to the people that worked behind the camera who are

the damnedest crew because they really were for the actor and put themselves

second. And if they saw something wrong they just went like this [makes

a tiny facial gesture], but didn't let anyone else see it, you know?

We would light generally. Light the whole picture generally and let

the actors

play it to the best of their ability. I would never tell an actor that

he is doing it wrong or that it doesn't connect with my interpretation.

I expect the actor to give me his interpretation. Obviously, if

he is lazy or doesn't take his part seriously, then I get out my knife,

my gun, my fist, and I kill him! I believe I have a gift as a director,

being able to create an atmosphere in which people can act naturally

in

any given situation. I don't try and control the scene, which is often

confused, anarchic, with the actors sometimes in league against me! that

Peter did he did himself. Everything that all those other actors did,

they did themselves. I give a lot of house – if there's any credit

to be given it is to the people that worked behind the camera who are

the damnedest crew because they really were for the actor and put themselves

second. And if they saw something wrong they just went like this [makes

a tiny facial gesture], but didn't let anyone else see it, you know?

We would light generally. Light the whole picture generally and let

the actors

play it to the best of their ability. I would never tell an actor that

he is doing it wrong or that it doesn't connect with my interpretation.

I expect the actor to give me his interpretation. Obviously, if

he is lazy or doesn't take his part seriously, then I get out my knife,

my gun, my fist, and I kill him! I believe I have a gift as a director,

being able to create an atmosphere in which people can act naturally

in

any given situation. I don't try and control the scene, which is often

confused, anarchic, with the actors sometimes in league against me!

People talk about improvisation

as if I say, "Everybody does what they want," and I take a camera

and a movie comes out. It doesn't work that way. Anybody who knows anything

about film knows that's crazy. Unless you're shooting a war maybe and

even there you have to look for action. There are no accidents in this

sense of the specific. A camera breaking down a location not available

me being broke those are accidents! You stay up all night long

and worry a film to death. To make the assumption that things just happen

like that is amazing to me. It doesn't happen that way with actors.

There's a lot I don't

understand. If I say we're gonna make a picture and we don't know what

we're doing, I'm absolutely straight when I say that. I don't think that

Gena has any idea when she comes on the set that she's going to be able

to break down, have a commitment scene, be frightened when she comes in.

I see her when I come home at night and I see her on the bed with the

script and I see her going over it and thinking about it and relating

to everything and preparing herself and asking me questions. I mean, Gena

reads this script and she takes and interprets that woman as someone that

is innocent. That's not my interpretation. That's not in

the script. You could interpret it as a person that fights it.

She interprets it as someone that's innocent. She's crazy, but

she's shy, too, really. She's not an outward person really. She's outward

because she thinks she's supposed to be. She wants to please somebody.

Gena has a lot of consideration for the character and the woman behind

the character. She tries never to vulgarize or caricature people she's

playing. She really resisted turning Mabel into a "victim" or

a "case" or a "feminist." That was her insight.

I'm

totally an intuitive person. I mean, I think about things that human

beings

would do, but I just am guessing – so I don't really have a preconceived

vision of the way a performer should perform. Or, quote, the character,

unquote. I don't believe in "the character." Once the actor's

playing that part, that's the person. And it's up to that person

to go in and do anything he can. If it takes the script this way and

that,

I let it do it. But that's because I really am more an actor than a director.

And I appreciate that there might be some secrets in people. And that

that might be more interesting than a "plot." All people are

really private – as a writer and a director, you understand that

that's

the ground rule: people are private. I'm

totally an intuitive person. I mean, I think about things that human

beings

would do, but I just am guessing – so I don't really have a preconceived

vision of the way a performer should perform. Or, quote, the character,

unquote. I don't believe in "the character." Once the actor's

playing that part, that's the person. And it's up to that person

to go in and do anything he can. If it takes the script this way and

that,

I let it do it. But that's because I really am more an actor than a director.

And I appreciate that there might be some secrets in people. And that

that might be more interesting than a "plot." All people are

really private – as a writer and a director, you understand that

that's

the ground rule: people are private.

* * *

Almost every

actor who worked with Cassavetes felt frustrated some of the time during

the shoot. They felt they desperately needed an explanation of some fact

or motivation; they craved a piece of information about their character;

they pleaded with him to tell them something they needed to know; and,

in almost every case, he refused to give them an answer. He would double-talk

them; he would give a meaninglessly vague response; he would stand silent

and look them deep in the eyes; but he would not give them a direct answer.

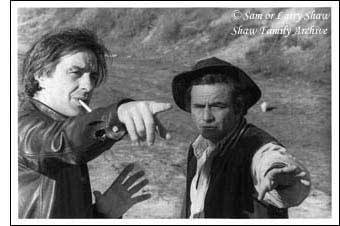

O. G. Dunn (who plays Garson

Cross) was uncertain how he was supposed to play his scenes. He

practically

begged Cassavetes to give him an action or a feeling to play. It would

have been the easiest thing in the world for Cassavetes to have

said something

like, "You're a gentle, polite man; you're not a brute, so you're not

going to force it; but you would like to sleep with this woman;

and she

did invite you home, so you think she probably wants to do it; but she

is a woman, and you have had woman problems in the past. So you

are not

sure what she expects . . ." That's the explanation a thousand other

directors would have given to actors in similar situations. But

it was the sort

of answer Cassavetes almost never gave. According to a crew member who

watched the whole exchange, what happened was closer to the following:

OGD: How should I play this?

JC: Look. You're here. She's there. You see? (Followed by a long, intense

look, which was the way Cassavetes often ended this sort of explanation.)

OGD: Well, yeah, John, but . . .

JC: No, no, no. Don't! Don't! Just. You know? (Followed by another

deep, soulful look.)

Thus it went, four or five

times in a row, until Dunn gave up in frustration and bewilderment. It's

the same sort of apparent inarticulateness

that drove Peter Falk crazy during the filming of Husbands. It's

not that Cassavetes could not have given a long, articulate explanation.

It's that he knew that

if he wanted Dunn to act convincingly hesitant and uncertain, the last

thing he could ever do was to tell him to act that way.

Actors always want to know,

how is it all going to work out? I don't know. Where does it lead?

I don't

know that either. The actor has to make a decision. I hate control. I'm

not a leader. I'm only happy where there's total confusion, where

people

function on their own level. You don't know what's gonna happen. You're

meeting twelve strangers and you see a bunch of people standing behind

the camera and there are lights all over the place and obviously it's

being lit for one specific area because all the lights are there.

So you

see that and you don't know what you're gonna do! So the question is,

at what point do I reveal what's going to happen? My system is never

to

reveal it! My system is to create as much confusion as I possibly can

so the actors have the full knowledge that they're on their own, that

there is nothing I'm ever going to tell them, ever, at any point in the

thing. Except if somebody would say, "I think I'm going too far,"

I would

disagree with them. Or if somebody would say, "Let's take a break," I

would disagree with them, you know? Or if somebody would small talk.

In

other words, "You are now to reveal your life and parts of your life

that you don't even know exist." I refuse to let myself or my characters

seek

refuge in psychology either for purposes of motivation or character analysis.

Cassavetes

deliberately created a state of insecurity in certain actors for

certain

scenes. Dr. Zepp was played by Eddie Shaw, Sam Shaw's brother. Eddie

was a sweet and gentle man, but as a novice non-actor he was extremely

insecure

about what he was doing. He barraged Cassavetes and everyone else on

the shoot with demands for reassurance – "How was I?" "Do

you think that was right?" "I didn't know if you could see my face

since

I was turned away."

"Was it good enough?" "Tell me exactly what you want me to do in the

next scene." Cassavetes was annoyed by the questions and was quite stern

with

him (as he was with many of the non-professionals on the shoot); but

he knew better than to attempt to stop them by answering them. He realized

that the actor's tentativeness could enrich the characterization. Cassavetes

deliberately created a state of insecurity in certain actors for

certain

scenes. Dr. Zepp was played by Eddie Shaw, Sam Shaw's brother. Eddie

was a sweet and gentle man, but as a novice non-actor he was extremely

insecure

about what he was doing. He barraged Cassavetes and everyone else on

the shoot with demands for reassurance – "How was I?" "Do

you think that was right?" "I didn't know if you could see my face

since

I was turned away."

"Was it good enough?" "Tell me exactly what you want me to do in the

next scene." Cassavetes was annoyed by the questions and was quite stern

with

him (as he was with many of the non-professionals on the shoot); but

he knew better than to attempt to stop them by answering them. He realized

that the actor's tentativeness could enrich the characterization.

I don't want big, long discussions;

I don't want to know what they're thinking. If an actor tells me, "Look,

I'm going to be this," and then tries to do it, he's putting untold

pressure

on himself. Eddie Shaw, he's the producer's brother, came in, and we

didn't have anyone to play the thing, and he said he'd play it. It

was the greatest

thrill in his life to play this doctor, so when he came in he kept on

saying, "What do I do?" I thought, "That's wonderful! That's a great

kind

of a doctor to have! That's the doctors I've known!" [Laughs.] This guy

says, "Where does it hurt?" Why should I tell him?

Mario Gallo (who plays

Mr. Jensen) was another friend whose personal feelings became part

of his

performance. Gallo was not entirely comfortable with Cassavetes' direction

and was fairly awkward or tentative in his playing, but Cassavetes

realized

that his "nervousness" should not be eliminated, but should be 'used'

in his performance.

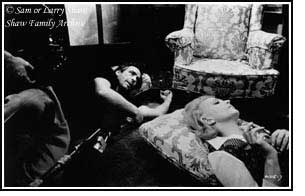

These

are fairly minor cases. Cassavetes' treatment of Rowlands and Falk is

a textbook example of the use of psychology to massage souls and spirits.

His relationship with Rowlands was extremely rocky at times (to the extent

that at one point he told her he would never work with her again). Rowlands

on her part felt lost at moments and desperately in need of help, which

Cassavetes seemed at times deliberately to withhold. Prior to shooting

the homecoming scene, Rowlands pleaded with her husband for guidance.

It was months into the shoot; she was tired and confused; more than information,

what she probably needed was a little reassurance. Cassavetes not only

refused to provide it but undermined what little confidence she had left

with the coldness and distance of his response. She wanted to be calmed

down; he did everything possible to work her up. These

are fairly minor cases. Cassavetes' treatment of Rowlands and Falk is

a textbook example of the use of psychology to massage souls and spirits.

His relationship with Rowlands was extremely rocky at times (to the extent

that at one point he told her he would never work with her again). Rowlands

on her part felt lost at moments and desperately in need of help, which

Cassavetes seemed at times deliberately to withhold. Prior to shooting

the homecoming scene, Rowlands pleaded with her husband for guidance.

It was months into the shoot; she was tired and confused; more than information,

what she probably needed was a little reassurance. Cassavetes not only

refused to provide it but undermined what little confidence she had left

with the coldness and distance of his response. She wanted to be calmed

down; he did everything possible to work her up.

GR: What do you want me to

do?

JC: I don't want to tell you. What would Mabel do?

GR: I don't know. Help me. Please! Come on! You could help me! Take me

outside. I don't know what she's . . .

JC: Gena, that's enough! I refuse to talk to you. No more!

By

this point Rowlands was glaring at him, really irritated and upset. She

was no longer pleading but angry, and started yelling at him, protesting

at the way he was treating her. Instead of trying to calm her down, he

then started taunting and mocking her back. The moment built with exchanged

charges and countercharges. Then Cassavetes suddenly turned on his heels

and walked away, leaving Rowlands alone in front of the actors and crew.

A few minutes after that, without saying anything else, he gave the order

to shoot the scene. By

this point Rowlands was glaring at him, really irritated and upset. She

was no longer pleading but angry, and started yelling at him, protesting

at the way he was treating her. Instead of trying to calm her down, he

then started taunting and mocking her back. The moment built with exchanged

charges and countercharges. Then Cassavetes suddenly turned on his heels

and walked away, leaving Rowlands alone in front of the actors and crew.

A few minutes after that, without saying anything else, he gave the order

to shoot the scene.

If the result was not one

of the greatest performances ever captured on film, Cassavetes' treatment

of Rowlands could be called heartless and brutal. What is even more interesting

is that when the cameras rolled Rowlands gave Cassavetes something he

never expected. It seems clear in retrospect that he was deliberately

winding her up to get anger, resentment or bitterness out of her in the

scene; but in response she gave innocence and vulnerability. Just as he

was shocked into dropping the camera during the breakdown scene, Cassavetes

later confessed that he was bewildered by the choices that ensued.

When Gena was committed by

Peter and she went to an institution, and as the film says, six months

later she comes out – I would have thought that she would be so

hostile against her husband. But she comes in the house and she never

even acknowledges

his presence. She's only considering her children. And we did a take,

and I thought, "Should I stop this? I mean, she never looked at Peter."

She walks in the house and everyone greets her and she never looks at

her husband – I mean, she looks at him, but she never sees him,

yet she's

not avoiding him. And I thought, "Well, that's that defenseless thing

carrying itself too far here! What are we doing?"

All through that homecoming

scene I was astounded by what was underneath people, what these actors

had gathered in the course of this movie. And I was way behind them. I

was staggered because Gena was so quiet and mild. She wasn't hostile at

all. I started yelling because I thought she was acting so the audience

would like her, but I was wrong. She was expressing fear, which separated

her from the people she loved. At the moment when Nick's mother, Mabel's

enemy, subtly changes her approach in the most malicious way, just at

the moment when the audience is hoping that Mabel is going to get out

of there, Mabel stays so tender. She wants to stick with her family to

the very end. If she'd come back from the asylum with hate in her heart,

the film couldn't finish the way it does. All through that homecoming

scene I was astounded by what was underneath people, what these actors

had gathered in the course of this movie. And I was way behind them. I

was staggered because Gena was so quiet and mild. She wasn't hostile at

all. I started yelling because I thought she was acting so the audience

would like her, but I was wrong. She was expressing fear, which separated

her from the people she loved. At the moment when Nick's mother, Mabel's

enemy, subtly changes her approach in the most malicious way, just at

the moment when the audience is hoping that Mabel is going to get out

of there, Mabel stays so tender. She wants to stick with her family to

the very end. If she'd come back from the asylum with hate in her heart,

the film couldn't finish the way it does.

Gena's interpretation showed

me how frightened Mabel was. As a matter of fact, when we looked at

the

dailies, Gena said, "What do you think? I'm at a loss, did we go too

far?" And I said, "I didn't like it, I just didn't like it at all."

I mean,

I found it really embarrassing to watch. It was such a horrible thing

to do to somebody, to take her into a household with all those people

after she'd been in an institution, and their inability to speak to this

woman could put her right back in an institution, and yet they were

speaking

to her, and Gena wanted to get rid of them and at the same time not insult

them. But then I thought what Gena did was like poetry. It altered

the

narrative of the piece. The dialogue was the same, but it really made

it different. I would grow to love those scenes very, very much, but

the

first time I didn't. The film really achieved something really remarkable

through the actors' performances, not giving way to situations but

giving

way to their own personalities.

Gena had taken away the pettiness

of women as a weapon. The woman in a sense became idealized; you took

the purity of a woman minus pettiness. One of the things we had worked

out in the beginning of the movie was that these characters could not

be petty because you would lose the whole intention of what the film was

about. Gena wasn't a hostile person and didn't use a weapon. Taking that

weapon away made the woman extremely vulnerable. No one is defensive in

the whole film. There isn't one shield on anybody's psyche, or anybody's

heart. It's just open.

It would be hard to find

a clearer illustration of how Cassavetes' "non-directive directing"

allowed

his actors to give him things he couldn't anticipate. He learned things

about his characters and their situations. He changed his mind as

he went

along.

As the shoot goes on all these

things that are happening are revelations to me also. I'm seeing Gena

do this, and Gena as my wife now suddenly is becoming Mabel Longhetti

and those pink socks are becoming something that you see on something.

Those nice legs are becoming Mabel's nice legs and her manner of insanity

is recognizable and suddenly she's not insane. These discoveries are happening

to me, to the crew and to the characters.

This

page only contains excerpts and selected passages from Ray Carney's writing

about John Cassavetes. To obtain the complete text as well as the complete

texts of many pieces about Cassavetes that are not included on the web

site, click

here.

|