|

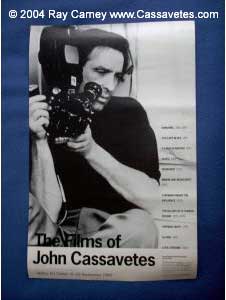

In his new book, The

Films of John Cassavetes: Pragmatism, Modernism, and the Movies (published

in paperback by Cambridge University Press), Boston University

Professor of American Studies and Film Ray Carney takes the reader behind

the scenes to watch the maverick independent at work: writing his scripts,

rehearsing his actors, blocking their movements, shooting his scenes,

and editing them. The iconoclastic, interdisciplinary study challenges

many accepted notions in film history and aesthetics. In the excerpt that

follows, which is taken from the final chapter, Professor Carney treats

Cassavetes' filmmaking as a form of thought, and argues that his work

offers new ways of thinking about thinking.

* * *

....There is a final reason

that none of Cassavetes' films was considered for admission into the

artistic

canon during his lifetime: Almost without exception, American filmmakers

and critics take for granted that art is essentially a Faustian enterprise – a

display of intellectual power, control, and mastery. They assume

that

a work's greatness is traceable to its ability to limit, shape, and organize

what the viewer sees, hears, knows, and feels in each shot. In a

word,

their conception of artistic performance is virtuosic. Leaf through the

pages of the standard film textbooks and what you will find is an

implicit

equation of virtuosity and greatness that extends to every aspect of

a film's creation: from the writer's ability to create "revelatory"

dialogue; to the director's, cameraman's, and lighting supervisor's ability

to use lighting, framing, camera angles, and movements to manipulate

what

the viewer knows and feels; to the editor's and musical supervisor's

ability to orchestrate the pacing and dramatic intensity of events down

to the

last beat.

Once one buys into this value

system it's not hard to see why Citizen Kane, Psycho, Blood

Simple, Blue Velvet, Manhattan, and Dressed to Kill

are regarded as artistic masterworks. Filmmaking within the virtuoso

tradition is essentially a celebration of knowing, and these films create

worlds in which everyone and everything of importance can be known. The

screenwriters, actors, crew, director, and the viewers all participate

in a community of psychological, emotional, and intellectual understanding.

Indeed, a large part of the critical and commercial appeal of such works

is that they allow the viewer and reviewer to feel that they become part

of this cult of complete and perfect knowledge, as they move, in the course

of the film, from confusion to clarity, from doubt to certainty, from

being "out" to being "in."

No

set of values could be more opposed to Cassavetes' belief about either

the process of living or the

function of art. For him making a film was not a display of power and

prowess, but was rather an act of humility. It did not involve virtuosic

arrangement and masterful organization, but patient exploration and tentative

discovery. As he often said, for his actors, his crew, his viewers,

and

himself, filmmaking was a matter of asking questions to which you didn't

know the answers and holding yourself tenderly open, ready to come

across

new questions at any moment. The work that resulted was an admission

of what you didn't know and might never be able to understand. It

was not

about moving from confusion to clarity – for the actor, the director,

or the viewer. Getting lost was the goal – being forced to break

your old habits and understandings, giving up your old forms of complacency.

The

way to wisdom was through not-knowing. The master plot of Cassavetes'

work – for himself, his actors, his characters, and his viewers – is

an antivirtuosic one: moving out of positions of power and control

and into

places of fear and uncertainty. That is why the narratives themselves

are almost always about going out of control. To allow yourself to

let

go was the first step in learning anything. Everything else was what

Cassavetes called "doing tricks" and "playing games" with

expression. No

set of values could be more opposed to Cassavetes' belief about either

the process of living or the

function of art. For him making a film was not a display of power and

prowess, but was rather an act of humility. It did not involve virtuosic

arrangement and masterful organization, but patient exploration and tentative

discovery. As he often said, for his actors, his crew, his viewers,

and

himself, filmmaking was a matter of asking questions to which you didn't

know the answers and holding yourself tenderly open, ready to come

across

new questions at any moment. The work that resulted was an admission

of what you didn't know and might never be able to understand. It

was not

about moving from confusion to clarity – for the actor, the director,

or the viewer. Getting lost was the goal – being forced to break

your old habits and understandings, giving up your old forms of complacency.

The

way to wisdom was through not-knowing. The master plot of Cassavetes'

work – for himself, his actors, his characters, and his viewers – is

an antivirtuosic one: moving out of positions of power and control

and into

places of fear and uncertainty. That is why the narratives themselves

are almost always about going out of control. To allow yourself to

let

go was the first step in learning anything. Everything else was what

Cassavetes called "doing tricks" and "playing games" with

expression.

What

is wrong with knowingness is that it removes us from the stimulating turmoil

of experience. It separates the individual from the scrambling confusion

of living because it figures a set of understandings worked out in advance

of or apart from the experience. For Cassavetes, thought was not something

that was done separate from, or that allowed you to rise above the turbulence

of experience, but rather was the process of hacking a path through an

experience as it happens. Another way of putting that is to say that,

for Cassavetes, filmmaking was not something that followed the living

or analyzed the living; it was the living. The styles of Hitchcock,

Welles, DePalma, and Lynch tell us that they use film to present ideas

and feelings that they have already worked out. They do their living and

thinking, and when they reach a certain point of clarity and resolution,

they summarize it in their work. That is why they can story-board their

scenes and decide on their camera angles before they ever walk onto the

set. They use the filmmaking process to push preselected buttons, to paint

by numbers. That is not what filmmaking was for Cassavetes. Every camera

movement or refocusing, every cut in his work tells us that for him making

a film was a way of wondering about an experience while you were having

it, not of reflecting on it from a distance. Filmmaking was exploring. What

is wrong with knowingness is that it removes us from the stimulating turmoil

of experience. It separates the individual from the scrambling confusion

of living because it figures a set of understandings worked out in advance

of or apart from the experience. For Cassavetes, thought was not something

that was done separate from, or that allowed you to rise above the turbulence

of experience, but rather was the process of hacking a path through an

experience as it happens. Another way of putting that is to say that,

for Cassavetes, filmmaking was not something that followed the living

or analyzed the living; it was the living. The styles of Hitchcock,

Welles, DePalma, and Lynch tell us that they use film to present ideas

and feelings that they have already worked out. They do their living and

thinking, and when they reach a certain point of clarity and resolution,

they summarize it in their work. That is why they can story-board their

scenes and decide on their camera angles before they ever walk onto the

set. They use the filmmaking process to push preselected buttons, to paint

by numbers. That is not what filmmaking was for Cassavetes. Every camera

movement or refocusing, every cut in his work tells us that for him making

a film was a way of wondering about an experience while you were having

it, not of reflecting on it from a distance. Filmmaking was exploring.

Rather

than art being a mirror held up to nature that gives back a pale, partial,

or distorted reflection of life, in this vision of it, art becomes

life

itself – life lived at its most intense, interesting, and engaged.

Henry James and Balzac never lived more excitingly and alertly than

when they

sat in a room writing, and Cassavetes never lived more sensitively or

passionately than when he was making his movies. As he rewrote his scripts,

darted about on his sets blocking out actions, or compared trial assemblies

in the Movieola, he was having experiences with the highest degree of

complexity that he could ever attain. In the filmmaking, he launched

himself on an adventure of discovery more thrilling, forward moving,

and excitingly

exploratory than even those experienced by the characters within his

films.

This

is thought at its fastest and most acute (and as my cross-references

throughout this book have been

meant to suggest, thought fully as profound and complex as what one encounters

in Emerson's and William James' philosophical writing), but we need

a

new definition to do it justice. Living in the shadow of Plato, all of

our thinking about thinking is tainted with a contemplative bias.

In the

Platonic view, thought is something that we do when we are not experiencing

life. It is an intermission from responding to events. It happens

in our

heads, not in our bodies. It is theoretical and intellectual, not active

and practical. It is rigorous, systematic, and consistent, not playful,

experimental, and revisionary. Our thinking about art is similarly biased – favoring

the distancing effects of contemplation over the involvements of action,

the stabilities of explanation over the turbulence of experience, the

essences of epistemology over the flowing movements of history. Cassavetes

reversed these valuations and practiced a different kind of thought – thought

not as a meditative step backward from the chaos of action and event,

but as a plunge into it; thought not as something static and detached

from experience, but as engaged and on the move; thought not as a time-out

from the pressures and limitations of experience, but as a path of performance

through them. This is thought unsupported by (and unfettered by) system

and theory and regularity; thought as a state of abandonment to the pursuit

of an impulse; thought allowing for continuous shifts and revisions

of

course. This

is thought at its fastest and most acute (and as my cross-references

throughout this book have been

meant to suggest, thought fully as profound and complex as what one encounters

in Emerson's and William James' philosophical writing), but we need

a

new definition to do it justice. Living in the shadow of Plato, all of

our thinking about thinking is tainted with a contemplative bias.

In the

Platonic view, thought is something that we do when we are not experiencing

life. It is an intermission from responding to events. It happens

in our

heads, not in our bodies. It is theoretical and intellectual, not active

and practical. It is rigorous, systematic, and consistent, not playful,

experimental, and revisionary. Our thinking about art is similarly biased – favoring

the distancing effects of contemplation over the involvements of action,

the stabilities of explanation over the turbulence of experience, the

essences of epistemology over the flowing movements of history. Cassavetes

reversed these valuations and practiced a different kind of thought – thought

not as a meditative step backward from the chaos of action and event,

but as a plunge into it; thought not as something static and detached

from experience, but as engaged and on the move; thought not as a time-out

from the pressures and limitations of experience, but as a path of performance

through them. This is thought unsupported by (and unfettered by) system

and theory and regularity; thought as a state of abandonment to the pursuit

of an impulse; thought allowing for continuous shifts and revisions

of

course.

When Charlie Parker and Dizzy

Gillespie were jamming together, they were thinking this way – not

deliberating in advance of the act, not reflecting on it from a distance,

not meditatively

rising above the pressures of the performance – but thinking in

deed and action. Their thought was the activity of negotiating both sensory

and

theoretical pressures and constraints, of performing with them and against

them, and of shaping a continuously adjusted path of advance along them.

In this non-Platonic model, the engagements of action replace the disengagements

of contemplation as a way of moving through life.

In these creative circumstances,

the nature of meaning itself changes. Whereas the Faustian filmmaker

sets

out to display an intellectual and emotional superiority to experience,

to bend it to make a series of predetermined "points," in

Cassavetes' vision of art, there is no argument, meaning, or point

to prove. There

is only exploring and moving on, with no end to the process of experiencing,

and no goal to reach. That is why he was indifferent to his films

as finished

products. As he often said, the films didn't matter. What mattered was

the doing, the learning, the scrambling, the growing, the discoveries

along the way. The work itself (as a series of characters, blockings,

camera angles, and editorial choices) was only the tracks left behind

as the artist moved through a set of challenging, stimulating experiences.

It was the historical record of a series of choices. What this entire

book has been devoted to demonstrating is that, to the most alert viewing,

that is what the films become again – not bodies of codified

knowledge, not a series of views, messages, or statements about

experience, but examples

of the experiences themselves.

This

is film not as about thought, or as documenting the conclusions

thought has arrived at, but as an act of thought in itself – as

a great jazz or dance performance is an act of thought. And like a lucky

recording of one of Louis Armstrong's or Charlie Parker's more exultant

solos, the film stands not as a statement about something, but

as a moving illustration of thought in action – thought at its most

brilliant and exciting, happening in the present tense. The films are

captured records of courses of events – experiences of living intensely,

responding rapidly, and feeling your way in the dark. They are enactments

of what it is like to live at the highest pitch of awareness, at a level

of engagement and responsiveness that we rarely reach in our lives. To

a viewer agile enough to keep up with their twists and turns, they become

inspiring examples of some of the most exciting, demanding paths that

can be taken through experience. It's as if Cassavetes hacked his way

through a jungle of experiences and we were left studying the moving record

of the trail his movements left behind. That is to say, the films are

records of movements, not presentations of positions. They display meanings

in motion that stay in motion. They offer a vision of a new form of truth

– truth not as a place of rest, truth not as a conclusion arrived

at, but as a path of performance within and against a series of ever-shifting

resistances. Cassavetes' films don't yield up meaning as a product, but

offer inspiring examples of the energy, intelligence, and emotional agility

it takes to have experiences of the most meaningful sort. This

is film not as about thought, or as documenting the conclusions

thought has arrived at, but as an act of thought in itself – as

a great jazz or dance performance is an act of thought. And like a lucky

recording of one of Louis Armstrong's or Charlie Parker's more exultant

solos, the film stands not as a statement about something, but

as a moving illustration of thought in action – thought at its most

brilliant and exciting, happening in the present tense. The films are

captured records of courses of events – experiences of living intensely,

responding rapidly, and feeling your way in the dark. They are enactments

of what it is like to live at the highest pitch of awareness, at a level

of engagement and responsiveness that we rarely reach in our lives. To

a viewer agile enough to keep up with their twists and turns, they become

inspiring examples of some of the most exciting, demanding paths that

can be taken through experience. It's as if Cassavetes hacked his way

through a jungle of experiences and we were left studying the moving record

of the trail his movements left behind. That is to say, the films are

records of movements, not presentations of positions. They display meanings

in motion that stay in motion. They offer a vision of a new form of truth

– truth not as a place of rest, truth not as a conclusion arrived

at, but as a path of performance within and against a series of ever-shifting

resistances. Cassavetes' films don't yield up meaning as a product, but

offer inspiring examples of the energy, intelligence, and emotional agility

it takes to have experiences of the most meaningful sort.

Cassavetes' supreme accomplishment

is that as a viewer watches his films he actively participates in the

same process of exploring, learning, wondering, and changing his mind

that the filmmaker did in making them. If we are nimble and strong enough,

we move through these experiences the way we move through life at our

best. The films themselves are the closest thing to life lived at its

most intense; they allow us the experience of fresh, growing, changing

experiences. That is why, in the end, we remember them only to be able

to forget them. We go to them only to leave them behind by moving beyond

them in our own experience. They bring us back to life.....

Excerpted from: "Meanings

in Motion: New Forms of Knowledge," The Boston Book Review,

Volume 1, number 2 (Winter 1994), p. 36; adapted from Ray Carney's The

Films of John Cassavetes: Pragmatism, Modernism, and the Movies (Cambridge

and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

To read more of Ray Carney's

views on film and film criticism, see the Films of John Cassavetes, Films

of Mike Leigh, and Independent Vision sections.

This

page only contains excerpts and selected passages from Ray Carney's writing.

To obtain the complete text of this piece as well as the complet texts

of many pieces that are not included on the web site, click

here.

|