|  ....I

remember hearing Cassavetes joke about the response to his films. Imitating

an imaginary viewer, he slouched down in his chair and flailed his arms

in front of his face, as if defending himself from the fury of an atomic

blast, all the while chortling: "Oh, no. A new experience. Save me.

Anything but that!" ....I

remember hearing Cassavetes joke about the response to his films. Imitating

an imaginary viewer, he slouched down in his chair and flailed his arms

in front of his face, as if defending himself from the fury of an atomic

blast, all the while chortling: "Oh, no. A new experience. Save me.

Anything but that!"

Films come in cans. Unfortunately,

most of the experiences in them are canned as well. "Look here.

Think this. Feel that." We laugh and cry on cue. It's button-pushing – nothing

like real experience.

Cassavetes gives us something

closer to the turbulence and turbidness of life. He asks us to turn off

the emotional Cruise Control and go off-road. The journey is bumpy and

unpredictable. Characters get in our faces (and under our skin). They

are as hard to figure out (and as changeable) as people outside the movies.

There's no orchestration to tell us what to feel. There's no narrative

road map to show us where we are going. It makes for a pretty rugged trip

at times.

Cassavetes isn't merely being

perverse. He wants to get us lost so that maybe, just maybe, we can

find

ourselves and meet the world in a new way. He wants to force us to throw

away all of our formulas, clichés, and customary patterns of response

in order to encounter life freshly. Disrupting our expectations, dislodging

our stereotypes, making things hard on us is one way to do that.

Love is another way. No filmmaker

had more faith in the power of emotion to show his characters and viewers

the way out of the traps their minds get them into. Love is the great

teacher because it forces us to open our hearts to new experiences. It

forces us to jettison our old ways of understanding.

But

don't look for swoony, moony "I-look-into-your-eyes; you-look-into-mine"

Hollywood romance in these films. That is just one more cliché

they shred. The films in this series tell the truth about love in all

of its glorious, painful, wondrous complexity. The truth about how vulnerable

it can make us. How scary it can be. How ferocious it can be at some times

and how delicate at others. The truth about how hard love is to hold on

to, and how fleeting it can be. But

don't look for swoony, moony "I-look-into-your-eyes; you-look-into-mine"

Hollywood romance in these films. That is just one more cliché

they shred. The films in this series tell the truth about love in all

of its glorious, painful, wondrous complexity. The truth about how vulnerable

it can make us. How scary it can be. How ferocious it can be at some times

and how delicate at others. The truth about how hard love is to hold on

to, and how fleeting it can be.

For Cassavetes, filmmaking

was question-asking. His films ask the hardest possible questions

about

the meaning of our lives and relationships – questions we might

not want to know the answers to. They force us to come face to face

with difficult

truths. But what is inspiring is that even after plunging into the darkest

corners of our hearts, the most tortured and twisted recesses of our

souls,

the films never despair or turn cynical. Cassavetes never abandons his

faith in the healing, redeeming power of love.....

* * *

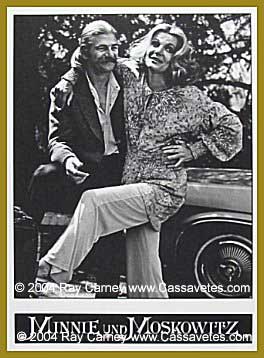

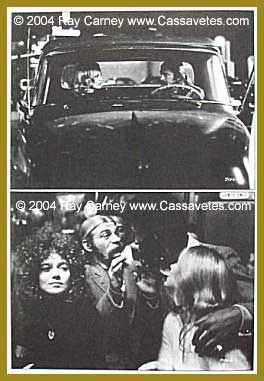

Has a comedy ever taken a viewer

on a wilder emotional roller-coaster ride? On the Cassavetes Comet,

we may chuckle as we chug up the romantic peaks, but are suddenly gasping

for breath when the intellectual ground drops out from under us, or emotionally

whiplashed as we scream around unexpected tonal curves. It's simply impossible

to sit back and get comfortable. We laugh at a joke, then get slapped

in the face by a character named Jim. Out on a blind date with Minnie

and Zelmo, we start giggling, then want to climb under our seats in embarrassment.

The tickle and the pain, the grin and the grimace are right on top of

each other. Has a comedy ever taken a viewer

on a wilder emotional roller-coaster ride? On the Cassavetes Comet,

we may chuckle as we chug up the romantic peaks, but are suddenly gasping

for breath when the intellectual ground drops out from under us, or emotionally

whiplashed as we scream around unexpected tonal curves. It's simply impossible

to sit back and get comfortable. We laugh at a joke, then get slapped

in the face by a character named Jim. Out on a blind date with Minnie

and Zelmo, we start giggling, then want to climb under our seats in embarrassment.

The tickle and the pain, the grin and the grimace are right on top of

each other.

Each time we start to kick

back, Minnie and Moskowitz kicks us back – gunning the

accelerator with dizzying elisions and jump-cuts; screeching on the

brakes to allow

a minor character a crazy solo riff; wildly swerving from toughness to

tenderness. No event unfolds in a straight line. The shortest distance

between any two points is a U-turn.

Every time a tone is about

to build, Cassavetes upsets it. Every time a relationship is about to

stabilize, he pulls the rug out from under it. In this emotional demolition

derby, it's impossible to recline into the featherbed of a simple, sustained

feeling. Like the jazz on the soundtrack, the pacings in Minnie and

Moskowitz are thrillingly irregular and unpredictably syncopated.

We can't get our tonal bearings. We don't know whether we're supposed

to laugh or cry most of the time.

Cassavetes won't let a viewer

expand within a romantic moment. No scene, interaction, or shot gives

us a simple emotion. If a scene has romance in it, it is invariably

crossed with anxiety or pain. If there is seriousness, it is mixed-up

with wacky comedy. If one character is feeling one thing, another is

feeling something different. Even the lovely meditative interlude in

which

Minnie talks to Florence about her dreams and desires makes clear that

Florence doesn't understand a word she is saying. While Minnie is waxing

poetic, Florence is sitting there bewildered and half-soused. Every

perspective

is tangled up with contradictory ones. No imaginative relationship – of

character to character or viewer to character – is uncompromised

or unchallenged.

No

filmmaker had a greater distrust of formulas for living or was more

committed to avoiding formulaic

characters and relationships. Cassavetes puckishly trampolines against

all of the ways Hollywood has taught us to think and feel. He turns

every

screwball formula upside-down and inside-out. Leading men are supposed

to be handsome, charming, and aloof; Seymour Moskowitz is a homely,

hot-blooded

carhop who tries to sleep with every woman he meets (succeeding with

two others beyond Minnie in the course of the film – though

one of his early sexual conquests, a night spent with Irish, the girl

in the bar, was cut

by the studio at the last minute). Leading ladies should be mysterious,

unattached, and virginal; Minnie Moore is in a relationship about

as far

from Irene Dunn and Cary Grant as can be imagined. No

filmmaker had a greater distrust of formulas for living or was more

committed to avoiding formulaic

characters and relationships. Cassavetes puckishly trampolines against

all of the ways Hollywood has taught us to think and feel. He turns

every

screwball formula upside-down and inside-out. Leading men are supposed

to be handsome, charming, and aloof; Seymour Moskowitz is a homely,

hot-blooded

carhop who tries to sleep with every woman he meets (succeeding with

two others beyond Minnie in the course of the film – though

one of his early sexual conquests, a night spent with Irish, the girl

in the bar, was cut

by the studio at the last minute). Leading ladies should be mysterious,

unattached, and virginal; Minnie Moore is in a relationship about

as far

from Irene Dunn and Cary Grant as can be imagined.

Even minor characters won't

be reduced to clichès. They are too human, too mixed-up, too complex,

too close to being us. There are no heroes or villains in Cassavetes'

universe. Zelmo (played by Cassavetes regular Val Avery) may be the blind

date from hell, but we can't demonize him. We can't even really hate him.

Cassavetes makes sure that we feel his neediness, his desperation, his

pain. Eternally damned to his own self-created hell, he clearly suffers

for his sins, torturing himself even more than he tortures Minnie, pushing

her away in the very attempt to get close to her. We are forced into sympathy

against our wills. Listen to the sobbing Cassavetes subtly lays in on

the soundtrack at the end of the fight scene.

The secret of Cassavetes' art

is that it is fundamentally an act of empathy. We are not asked to stand

outside and judge (as in an Altman film), but to go inside and understand.

We can't hold ourselves above the characters, untouched by them, superior

to them. Cassavetes opens trap doors into their consciousnesses, so that

they are given the chance to explain themselves and justify their actions.

We are forced to see things from their perspectives, feeling what

they feel. No one is generic, a type; everyone is a unique individual.

Morgan Morgan (played by Tim Carey), odd duck that he is, touches us with

his bonhomie and lame attempts at humor. Florence's sad loneliness and

confession of sexual frustration move her beyond being simply comical.

We can't merely laugh at any of Cassavetes' characters; we are forced

to care.

Cassavetes'

films are not ultimately about actions and events, but feelings. They

are not about what characters

do, but what they are and can be. The central dramatic

issue faced by the figures in Minnie and Moskowitz is that they

are each imprisoned in doomed ways of being – trapped by limiting

emotions, memories, and experiences. The masterplot of all of Cassavetes'

work is

the question of whether – emotionally wounded and beset with problems

as they may be – characters can keep alive possibilities of love

and caring. Heaped with pressures as they are, can they find a way to

hold onto their

innocence and vulnerability? Cassavetes'

films are not ultimately about actions and events, but feelings. They

are not about what characters

do, but what they are and can be. The central dramatic

issue faced by the figures in Minnie and Moskowitz is that they

are each imprisoned in doomed ways of being – trapped by limiting

emotions, memories, and experiences. The masterplot of all of Cassavetes'

work is

the question of whether – emotionally wounded and beset with problems

as they may be – characters can keep alive possibilities of love

and caring. Heaped with pressures as they are, can they find a way to

hold onto their

innocence and vulnerability?

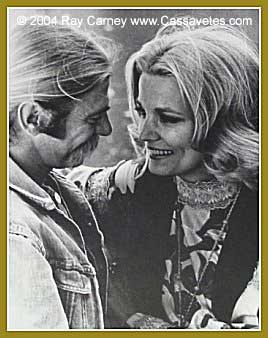

The specific focus of Minnie

and Moskowitz is culturally inherited forms of masculinity and

femininity – especially

as handed down to us by Hollywood movies. The film is an echo chamber

of compared and contrasted versions of what it is to be a man or

a woman

in modern America. Minnie (brilliantly played by Gena Rowlands to bring

out her shell-shocked vulnerability as a result of the romantic

battles

she has had to fight) must find a new way of being a woman. She must

get over her fears of being wounded, and learn how to give love

without giving

herself away, how to receive it without losing track of who she is.

Moskowitz

is Cassavetes' attempt to imagine a new form of manhood that avoids the

pushiness, competitiveness, and emotional guardedness of male culture.

(As Faces, The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, and Love

Streams show, one of Cassavetes' great themes is what it is to be

a man.) Cassavetes plunks Seymour down in a house of mirrors comprised

of alternative, flawed images of manhood – from Humphrey Bogart,

Wallace Beery, and Charles Boyer (Cassavetes had wanted to include a clip

from Algiers), to Zelmo, Morgan, Jim, and Dick Henderson. Cassavetes

has Moskowitz's scenes, gestures, and lines of dialogue subtly echo Zelmo's

and Jim's, to bring out both the differences and the similarities. As

Seymour Cassel wonderfully plays the character, Moskowitz represents a

rejection of male intellectualism, coolness, and distance in favor of

utterly uncool emotional expressiveness. (Moskowitz is in many respects

a spiritual self-portrait of the artist who created him.) He is Cassavetes'

Boudu – in fact, more interesting and complex than Renoir's figure,

because he is less abstracted and idealized. Moskowitz

is Cassavetes' attempt to imagine a new form of manhood that avoids the

pushiness, competitiveness, and emotional guardedness of male culture.

(As Faces, The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, and Love

Streams show, one of Cassavetes' great themes is what it is to be

a man.) Cassavetes plunks Seymour down in a house of mirrors comprised

of alternative, flawed images of manhood – from Humphrey Bogart,

Wallace Beery, and Charles Boyer (Cassavetes had wanted to include a clip

from Algiers), to Zelmo, Morgan, Jim, and Dick Henderson. Cassavetes

has Moskowitz's scenes, gestures, and lines of dialogue subtly echo Zelmo's

and Jim's, to bring out both the differences and the similarities. As

Seymour Cassel wonderfully plays the character, Moskowitz represents a

rejection of male intellectualism, coolness, and distance in favor of

utterly uncool emotional expressiveness. (Moskowitz is in many respects

a spiritual self-portrait of the artist who created him.) He is Cassavetes'

Boudu – in fact, more interesting and complex than Renoir's figure,

because he is less abstracted and idealized.

Hollywood film is based on

idealizations of every sort, at every level. Cassavetes radically de-idealizes

experience and expression....

This page only

contains excerpts and selected passages from Ray Carney's writing about

John Cassavetes. To obtain the complete text as well as the complete texts

of many pieces about Cassavetes that are not included on the web site,

click

here. |