|

This page only

contains excerpts and selected passages from Ray Carney's writing about

John Cassavetes. To obtain the complete text as well as the complete texts

of many pieces about Cassavetes that are not included on the web site,

click

here.

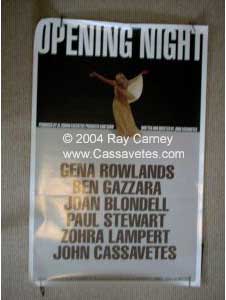

[Opening

Night] is the other side of A Woman Under the Influence, about

a woman on her own, with no responsibility to anyone but herself, with

a need to come together with other women. [Myrtle] is alone and in desperate

fear of losing the vulnerability she feels she needs as an actress. [She

is] a woman unable any longer to be regarded as young: Sex is no longer

a viable weapon. You never see her as a stupendous actress. As a matter

of fact, her greatest thrill was comfort, as it is for most actresses.

Give me a play I can go into every night and can feel I have some awareness

of who I am, what I am. [She didn't] want to expose myself in [certain]

areas. So when she faints and screams on the stage, it's because it's

so impossible to be told you are this boring character, you are aging

and you are just like her. I would be unable to go on to the stage feeling

that I'm nothing. I think that most actors would, and that's really what

the picture is about. Although she resists [facing them,] Myrtle must

finally accept and resolve the dilemmas which lie not only at the core

of the play she is doing, but which [reflect] the basic realities of her

own existence, from which she has heretofore fled, aided by alcohol, men,

professional indulgence – and fantasy! The character is left in

conflict, but she fights the terrifying battle to recapture hope. And

wins! In and out of life the theme of the play haunts the actress until

she kills the young girl in herself. [Opening

Night] is the other side of A Woman Under the Influence, about

a woman on her own, with no responsibility to anyone but herself, with

a need to come together with other women. [Myrtle] is alone and in desperate

fear of losing the vulnerability she feels she needs as an actress. [She

is] a woman unable any longer to be regarded as young: Sex is no longer

a viable weapon. You never see her as a stupendous actress. As a matter

of fact, her greatest thrill was comfort, as it is for most actresses.

Give me a play I can go into every night and can feel I have some awareness

of who I am, what I am. [She didn't] want to expose myself in [certain]

areas. So when she faints and screams on the stage, it's because it's

so impossible to be told you are this boring character, you are aging

and you are just like her. I would be unable to go on to the stage feeling

that I'm nothing. I think that most actors would, and that's really what

the picture is about. Although she resists [facing them,] Myrtle must

finally accept and resolve the dilemmas which lie not only at the core

of the play she is doing, but which [reflect] the basic realities of her

own existence, from which she has heretofore fled, aided by alcohol, men,

professional indulgence – and fantasy! The character is left in

conflict, but she fights the terrifying battle to recapture hope. And

wins! In and out of life the theme of the play haunts the actress until

she kills the young girl in herself.

—John Cassavetes

|

|

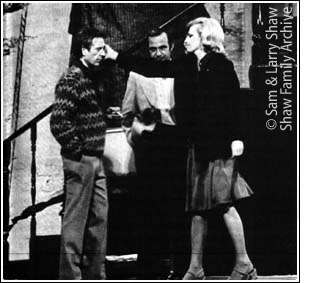

....What

sets Myrtle apart from each of the others in the acting company is that

each of them has cut a deal with life in one way or another, while she

refuses to compromise her definition of herself. While they shy away from

emotional danger, uncertainty, or exposure (constantly trying to calm

Myrtle down and talk her out of her distress), she keeps opening herself

up to new and painful personal recognitions. At one point or other in

the film, Kelly, Manny, Sarah, Maurice, and David each tell her a story

about how they have accepted limitations on their definitions of themselves

– made compromises which Myrtle (and her creator) utterly refuse

to accept. As we hear in their weary, resigned, business-like tones of

voice as early as the initial scenes outside the stage door and in the

limo, they are, in their different ways, at this point in their lives,

only going through the motions. They have decided who they are and what

their lives mean, and have accepted the definition as final – something

all of Cassavetes' work is opposed to. ....What

sets Myrtle apart from each of the others in the acting company is that

each of them has cut a deal with life in one way or another, while she

refuses to compromise her definition of herself. While they shy away from

emotional danger, uncertainty, or exposure (constantly trying to calm

Myrtle down and talk her out of her distress), she keeps opening herself

up to new and painful personal recognitions. At one point or other in

the film, Kelly, Manny, Sarah, Maurice, and David each tell her a story

about how they have accepted limitations on their definitions of themselves

– made compromises which Myrtle (and her creator) utterly refuse

to accept. As we hear in their weary, resigned, business-like tones of

voice as early as the initial scenes outside the stage door and in the

limo, they are, in their different ways, at this point in their lives,

only going through the motions. They have decided who they are and what

their lives mean, and have accepted the definition as final – something

all of Cassavetes' work is opposed to.

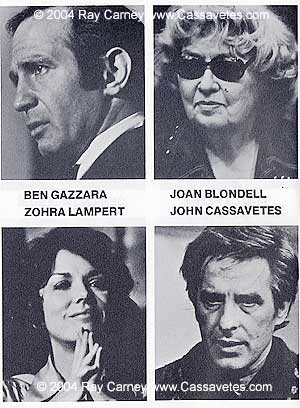

Director

Manny Victor and producer David Samuels use their avuncular manner, their

male poise, irony, and humor to hold emotions at arm's length. Former

boyfriend Maurice withdraws from emotional vulnerability into cynicism

and disillusionment. Writer Sarah Goode makes another kind of compromise.

She urges resignation and acceptance of old age. Her advice to Myrtle

as an actress – "All you have to do is say the lines clearly

and with a degree of feeling" (which represents the diametrical opposite

of everything Cassavetes believed about acting) – is all-too-clearly

her own defeatist strategy for mindlessly gliding through work and personal

relationships. She has quit living and begun dying. (Cassavetes subtly

metaphorizes Sarah's state of emotional guardedness and withdrawal by

having her hide behind the brim of a feathered cloche in most of her scenes.

Note the difference in the emotional coloring of the few scenes in which

Sarah is not wearing it.) Nancy Stein, the young fan who precipitates

Myrtle's breakdown, has an equally stunted sense of her identity. She

uses her physical beauty and the promise of sex as a way of manipulating

others, rather than opening herself to them in intimacy and vulnerability. Director

Manny Victor and producer David Samuels use their avuncular manner, their

male poise, irony, and humor to hold emotions at arm's length. Former

boyfriend Maurice withdraws from emotional vulnerability into cynicism

and disillusionment. Writer Sarah Goode makes another kind of compromise.

She urges resignation and acceptance of old age. Her advice to Myrtle

as an actress – "All you have to do is say the lines clearly

and with a degree of feeling" (which represents the diametrical opposite

of everything Cassavetes believed about acting) – is all-too-clearly

her own defeatist strategy for mindlessly gliding through work and personal

relationships. She has quit living and begun dying. (Cassavetes subtly

metaphorizes Sarah's state of emotional guardedness and withdrawal by

having her hide behind the brim of a feathered cloche in most of her scenes.

Note the difference in the emotional coloring of the few scenes in which

Sarah is not wearing it.) Nancy Stein, the young fan who precipitates

Myrtle's breakdown, has an equally stunted sense of her identity. She

uses her physical beauty and the promise of sex as a way of manipulating

others, rather than opening herself to them in intimacy and vulnerability.

Dorothy Victor is, in a sense,

the most interesting of Myrtle's imaginative alter egos. Dorothy

reminds a viewer of no one more than Maria Forst, the shy housewife of

Faces, who sold her identity out to her husband only to wake up

one day and realize that she had nothing left of herself. Silently, passively

identifying with Myrtle's on-stage struggle (like a reincarnation of Nancy),

Dorothy seems to undergo her own "opening night" in the course

of the film, but even so, it is telling that (like Myrtle's fans) she

lets Myrtle do the struggling for her, living vicariously through

Myrtle the way she previously lived vicariously through Manny.

Cassavetes

surprised me once by saying how much he admired Meet John Doe.

Capra's darkest and most problematic work seemed a peculiar choice until

I considered how much its title character anticipated some of Cassavetes'

imaginatively fragmented figures. Myrtle Gordon's problem, if one can

call it that, is that she wants to hold onto the fantasy that she can

be anything, even as she is continuously being reminded of imaginative

destinies which time and life deny her. As an actress and a woman, she

wants to keep all her imaginative doors open, even as her past choices

have shut them on her. Cassavetes

surprised me once by saying how much he admired Meet John Doe.

Capra's darkest and most problematic work seemed a peculiar choice until

I considered how much its title character anticipated some of Cassavetes'

imaginatively fragmented figures. Myrtle Gordon's problem, if one can

call it that, is that she wants to hold onto the fantasy that she can

be anything, even as she is continuously being reminded of imaginative

destinies which time and life deny her. As an actress and a woman, she

wants to keep all her imaginative doors open, even as her past choices

have shut them on her.

Though audiences may not want

to accept it, one of the points of the film is that you can't be

everything – that Myrtle has to let go of some possible destinies

in order to embrace others. She must "kill" Nancy in order

herself to live. She must come to grips with what she isn't and

can never again be,

in order to be what she is. Myrtle fights that recognition. She wants

to think of herself as still sexy and attractive, but she is, after

all,

a woman of a certain age. She wants to feel that she has not closed off

possibilities, that she can still be anything, but she can't. Cassavetes

goes against everything our culture tells us. He reminds us that we can't

be everything if we would be something. We must incur real losses,

real

pains, real failures, to gain anything at all.

Yet

at the same time, even to struggle with these questions, to fight and

resist them, is to prove that your life is not over, and all of the fundamental

issues are not resolved. Myrtle's triumph is that, no matter what price

in pain and suffering, no matter how many times she is berated, humiliated,

or rejected (as she is even on the next to last night of the film –

in the insulting encounter between her and Maurice in his apartment building),

she won't give up. Her desperation, her excesses, her stubborn refusal

to meet people half-way, to accept their limiting points of view, make

her "impossible," but also make her growth possible. Myrtle

bets her life, which is the only thing that can allow her to save it.

She refuses to exorcise her demons and wash her hands of them (as the

sèance scene metaphorically invites her to) until she has wrestled

them to the death. Cassavetes shows us that it is only in taking our lives

in our hands, in risking absolutely everything – our careers,

our friendships, and our loves – that life-saving truth can ever

be attained.... Yet

at the same time, even to struggle with these questions, to fight and

resist them, is to prove that your life is not over, and all of the fundamental

issues are not resolved. Myrtle's triumph is that, no matter what price

in pain and suffering, no matter how many times she is berated, humiliated,

or rejected (as she is even on the next to last night of the film –

in the insulting encounter between her and Maurice in his apartment building),

she won't give up. Her desperation, her excesses, her stubborn refusal

to meet people half-way, to accept their limiting points of view, make

her "impossible," but also make her growth possible. Myrtle

bets her life, which is the only thing that can allow her to save it.

She refuses to exorcise her demons and wash her hands of them (as the

sèance scene metaphorically invites her to) until she has wrestled

them to the death. Cassavetes shows us that it is only in taking our lives

in our hands, in risking absolutely everything – our careers,

our friendships, and our loves – that life-saving truth can ever

be attained....

This page only

contains excerpts and selected passages from Ray Carney's writing about

John Cassavetes. To obtain the complete text as well as the complete texts

of many pieces about Cassavetes that are not included on the web site,

click

here.

|