|  ....Written

immediately after he finished playing the starring role in Paul Mazursky's

Tempest and filmed after he had already begun to be ill, Love

Streams is Cassavetes' Prospero-like farewell to his art. He weaves

dozens of references to his previous work into the movie and waves good-bye

to his audience in the final shot. ....Written

immediately after he finished playing the starring role in Paul Mazursky's

Tempest and filmed after he had already begun to be ill, Love

Streams is Cassavetes' Prospero-like farewell to his art. He weaves

dozens of references to his previous work into the movie and waves good-bye

to his audience in the final shot.

Love Streams asks

the question of how can we keep the possibilities of love alive in

a world

in which love is never less than difficult at best. The film follows

the destiny of a couple at the end of everything – Robert, a

Hollywood hilltop recluse who has decided that "love is a fantasy

for little girls"

and that sex is all that is real; and Sarah who refuses to abandon her

romantic dreams even when her love life comes crashing down around her.

Cassavetes told me that the

sequence in which Robert and Sarah sit in the kitchen late one night and

talk about whether "love is an art" was his favorite scene.

Its beauty is that, like everything else in the film, it takes its

time. The viewer participates in a slow, delicate unfolding in which

a man and a woman briefly come together and then draw apart. Cassavetes'

vision is profoundly temporal in nature. All of life is flowing, streaming,

in motion. Everything is surging, opening, and closing. Nothing stands

still. Not even truth or love. Life takes time to live. Intimacy takes

time to develop. Love takes time to grow. Relationships take time to mature.

Of course, what is made in

time is always in danger of coming apart in time. That is why nothing

is ever final or ultimate or permanent in Cassavetes' work. Everything

is forever in transit, in process, unendingly being born and dying. Even

in this film about endings, Cassavetes shows us that life and love are

always beginning anew....

* * *

Critics

sometimes talk as if great art gives us new thoughts, when it would

be more accurate to say

it gives us new powers. If Cassavetes' work is about transforming his

characters, it is even more about transforming his viewers. To watch Faces,

A Woman Under the Influence, or Love Streams is to be given

new capacities of sensitivity and awareness – something much greater

and more revolutionary than new ideas. Cassavetes gives us new forms

of perception,

not just new meanings. Critics

sometimes talk as if great art gives us new thoughts, when it would

be more accurate to say

it gives us new powers. If Cassavetes' work is about transforming his

characters, it is even more about transforming his viewers. To watch Faces,

A Woman Under the Influence, or Love Streams is to be given

new capacities of sensitivity and awareness – something much greater

and more revolutionary than new ideas. Cassavetes gives us new forms

of perception,

not just new meanings.

Specifically, he trains us

to watch the faces, bodies, and voices of his characters with unusual

acuity. No filmmaker has done more to make the subtlest nuances of body

language the fundamental building blocks of meaning. Every film might

be said to be acted, but virtually no film is acted to the extent Cassavetes'

are – none relies more heavily on the viewer's ability to read

the tiniest facial flickers of emotion or listen to tonal demisemiquavers

with greater

sensitivity. It is as if the very atoms of the soul were put under a

microscope and made visible as they vibrated in place or darted back

and forth between

characters.

Although Cassavetes' work is

dramatically structured in quite elaborate ways (Faces, for example,

consisting of an intricate network of sexual comparisons and contrasts,

A Woman Under the Influence employing allusions to Rebel Without

a Cause and a series of operatic and balletic visual and acoustic

stylizations, The Killing of a Chinese Bookie drawing on Sternbergian

and Wellesian notions of art, Minnie and Moskowitz tweaking and

teasing Hollywood forms of expression), to a remarkable degree, Cassavetes'

meanings are not created with general stylistic effects or narrative

forms of organization (the way meanings in most other American films are),

but emanate from the faces, bodies, and voices of specific performers.

While, in the other sort of film, we watch how the frame is composed,

how a character is lighted, how the camera moves or doesn't move, etc.,

Cassavetes' work cultivates different ways of seeing and hearing. We are

not looking at the lighting or framing, but attending to butterfly flutters

of feeling in a character's face; we are not listening to the sound design,

but vibrating to birdsong vocal tremulations in a character's voice.

That

is, in fact, why most serious American film scholars have ignored Cassavetes'

work. The films are treated as if they were merely the record of dramatic

performances imagined somehow to be independent of them as films.

The thinking goes that when we watch a movie like Citizen Kane,

2001, or Apocalypse Now, we feel the director's presence

and choices in more or less every shot, since we are awash in generalized

stylistic effects of lighting, framing, and sound. When we watch Cassavetes,

the argument runs, we are not exposed to the choices of the director but

those of the performers. Ergo, his work is an "actor's cinema"

– in other words, a form of filmmaking not truly "cinematic." That

is, in fact, why most serious American film scholars have ignored Cassavetes'

work. The films are treated as if they were merely the record of dramatic

performances imagined somehow to be independent of them as films.

The thinking goes that when we watch a movie like Citizen Kane,

2001, or Apocalypse Now, we feel the director's presence

and choices in more or less every shot, since we are awash in generalized

stylistic effects of lighting, framing, and sound. When we watch Cassavetes,

the argument runs, we are not exposed to the choices of the director but

those of the performers. Ergo, his work is an "actor's cinema"

– in other words, a form of filmmaking not truly "cinematic."

The way out of the definitional

trap is to realize that the decision to make faces, bodies, and voices

the sources of meaning is as much an expression of the director's values

and vision as the decision to downplay the expressiveness of such things

in the other sort of film. The values are just different. That is to say,

Cassavetes' style is as cinematic as Hitchcock's. It just figures an entirely

different understanding of life and expression.

While the stylistic practices

of conventional cinematic expression (the use of light, sound, camerawork,

framing, and various symbolic and metaphoric forms of presentation) generalize,

abstract, and allegorize experience, the expressive embodiments of Cassavetes'

style physicalize, individualize, and particularize it. Hitchcock's characters

and situations are generic, representative, dreamlike; Cassavetes' are

unique, specific, localized. Hitchcock gives us Everyman doing anything;

Cassavetes gives us someone doing something.

Even more importantly, in the

stylistically inflected film, meaning is tipped toward the visionary.

It expresses more or less disembodied, imaginative states (and is apprehended

by the viewer's identification with and participation in such states of

abstraction and disengagement). Experience is turned into a mental event.

In Cassavetes' work, meaning and experience are practical, engaged, worldly.

Insofar as meaning inheres in the body and is expressed through practical

social interactions (and through the viewer's intricate perceptual negotiation

of those interactions as he or she watches the film), meaning is not in

the mind, but in the world. Cassavetes lowers his figures' centers of

gravity and moves his characters and viewers away from states of unworldly

vision and into practical acts of social negotiation. (Cosmo shows us

Cassavetes' feelings about visionary stances and relations.) Characters

are not their thoughts, feelings, and intentions, but their gestures,

tones of voice, and bodily expressions.

Finally, stylistic effects,

as they occur in the mainstream film, to a large extent, stand still.

If an interaction is kick-lighted one moment it will tend to be kick-lighted

the next; if the music is suspenseful at the start of a scene it will

generally still be suspenseful a minute later. In Cassavetes' work, because

the meanings are a matter of particulars of timing, pacing, body language,

facial expression, and vocal tone, nothing will stop moving or summarize

itself in this way. Meaning is as labile as voice tones and facial expressions.

To watch these films is to inhabit a world of exhilaratingly, scarily,

shifting meanings. There is no predicting the next beat.

Not

only can Richard and McCarthy or Nick and Mabel tonally be at knife

point one moment and cozy buddies

the next, but even in getting from one point to the other, they can go

through dozens upon dozens of incremental, zig-zagging swerves of

expression.

In Love Streams Sarah and Jack cycle through twenty or more tones

and relations to each other, Judge Dunbar, and Debbie in the hearing

room

in three or four minutes. To watch Robert interact with Albie at the

bar or with the transvestites in the nightclub is to watch meanings

that shift

from second to second. It's an extraordinary place to get a work of art

to – where streams of microscopic energy are flowing, coruscating,

flickering more rapidly than we can keep up with them. There is no

Archimedian stylistic

point outside of the flow by which we can get theoretical leverage on

it. Not

only can Richard and McCarthy or Nick and Mabel tonally be at knife

point one moment and cozy buddies

the next, but even in getting from one point to the other, they can go

through dozens upon dozens of incremental, zig-zagging swerves of

expression.

In Love Streams Sarah and Jack cycle through twenty or more tones

and relations to each other, Judge Dunbar, and Debbie in the hearing

room

in three or four minutes. To watch Robert interact with Albie at the

bar or with the transvestites in the nightclub is to watch meanings

that shift

from second to second. It's an extraordinary place to get a work of art

to – where streams of microscopic energy are flowing, coruscating,

flickering more rapidly than we can keep up with them. There is no

Archimedian stylistic

point outside of the flow by which we can get theoretical leverage on

it.

That's what makes Cassavetes'

films so different from their summaries or the memory of them. In summary,

A Woman Under the Influence might seem like a fairly clichéd depiction

of "a misunderstood, neurotic housewife" (as one early reviewer

put it). In actual experience, it is entirely different. The summary doesn't

even come close to touching the actual experience of what we see and hear.

It is not a film of generalizations, but of startling, unclassifiable,

individualized, unpredictable, astonishing details. Consider just

the first two or three minutes in which we see Mabel: the way she is dressed,

her hopping around on one foot, the way she rides the bike to the car,

the way it won't fit into the trunk, the way the trunk won't close, the

way the car stalls (a detail added in post-production), her shimmering

tones. Nothing is generic, representative, or indicated. Every instant

is new. Every local detail stunningly realized.

To

cycle back to my beginning, that is ultimately what it means to say that

Cassavetes' works are perceptual more than intellectual events. To put

it more precisely, one might say that they redefine intellect as perception.

Sarah and Mabel aren't a set of ideas about women (the way Thelma

and Louise are); they are a set of specific events. Cassavetes' films

are all details – all the way down to the ground. They tell

us that specifics are, in fact, all there are. To

cycle back to my beginning, that is ultimately what it means to say that

Cassavetes' works are perceptual more than intellectual events. To put

it more precisely, one might say that they redefine intellect as perception.

Sarah and Mabel aren't a set of ideas about women (the way Thelma

and Louise are); they are a set of specific events. Cassavetes' films

are all details – all the way down to the ground. They tell

us that specifics are, in fact, all there are.

The de-ideologization of Cassavetes'

depictions, the semantic embodiment of his expressions, the emphasis on

perceptual events figures a comprehensive vision of all of experience.

T.S. Eliot said of Henry James that he had a mind too fine for an idea

to violate it, and of Cassavetes it might be put more strongly: In his

work ideas are opposed to understanding. Like William James, Cassavetes

saw conceptual relations to experience (including the ones that generalized

stylistic effects create and the ones critics that explicate such films

habitually indulge in) as betraying it, because they abstract us from

and stop the motion of life. While sensory experiences never pause, ideas

stand still. All of Cassavetes' work is an effort to capture the feeling

of unconceptualized experience, to replace conceptions with perceptions.

He tells us we must learn to think without ideas.

One might say that the reason

Cassavetes' films feel so different from mainstream works is that

he is

doing nothing less than swimming against the entire Western intellectual

tradition as it was inflected by Plato – contravening two millennia

of post-Platonic contemplativeness, dephysicalization, disembodiment,

and

spiritualization.

The attack on abstractions

is not only enacted in the viewing experience of the films but dramatized

by the situations of the characters. Figures like Shadows' Lelia,

Faces' Maria, Minnie and Moskowitz's Minnie, and Love

Streams' Sarah are asked to put aside the intellectual burden of their

memories, learn to live in the present, and enter into fresh, nonconceptualized

relations to their own experiences. (Some rise to the challenge, and some

don't in the course of their narratives.) Like the viewers of these films,

the characters in them are asked to learn to flow with the perceptual

flow of life. The attack on abstractions

is not only enacted in the viewing experience of the films but dramatized

by the situations of the characters. Figures like Shadows' Lelia,

Faces' Maria, Minnie and Moskowitz's Minnie, and Love

Streams' Sarah are asked to put aside the intellectual burden of their

memories, learn to live in the present, and enter into fresh, nonconceptualized

relations to their own experiences. (Some rise to the challenge, and some

don't in the course of their narratives.) Like the viewers of these films,

the characters in them are asked to learn to flow with the perceptual

flow of life.

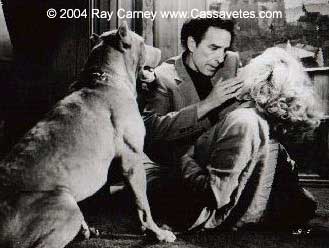

Figures like Robert in Love

Streams (or Richard, Zelmo, and Cosmo in earlier works) are judged

negatively precisely because of their inability to open themselves to

the flux of experience in this way. Robert is a Beverly Hills Thoreauvian.

Like a big budget re-incarnation of Cosmo Vitelli, he has built himself

an imaginative tree-house and pulled up the ladder. He lives the Coleridgean

dream of creating a Xanadu within which the self can imaginatively wall

out disturbance. (I was told, not by Cassavetes, that Robert's character

may have been loosely based on the life of Leonard Bernstein or someone

else the filmmaker knew.)

Robert's goal is to play all

of the parts in a one-man show of his own scripting, directing, and

producing. As exemplified by the scene in which he "interviews"

Joannie or makes a "research trip" to a gay bar, Robert declines

to participate in any relationship which he can't stage-manage – which

is why he dates girls decades younger than himself, sleeps with more

than

one at a time, and flees from the dangers of real openness or intimacy

with anyone. His unflappable aplomb ("Can I have your card?")

is his ultimate buffer from reality. It utterly walls out human contact.

If we know how to read them, the gestures, tones, and body language in

the scene between him and Susan on his front steps speaks volumes.

(Cassavetes

asked Peter Bogdanovich to photograph this particular scene.)

As much as Shakespeare, Cassavetes

was nothing if not the poet of saving disruptions and disturbances. His

films are dynamite sticks designed to blast through the walls of complacency

and comfort his characters (and viewers) erect around themselves. In The

Killing of a Chinese Bookie Cassavetes brings the Mob into Cosmo's

life; in Gloria he brings Phil into Gloria's; and here he brings

three intruders into Robert's island kingdom: a new girlfriend, a child

from a previous marriage, and Sarah. If the first two fail to get to him,

to scratch his Teflon veneer, Sarah succeeds in reaching him emotionally

at a depth no one apparently ever has before. She is Cassavetes' response

to Robert's dreams of closure and completeness. She is a principle of

imbalance. She tells us that nothing is secure, that everything is always

open to redefinition.

Cassavetes refused to meet

the viewer more than half-way. He would not cut his sense of truth to

fit the prefabricated emotional and intellectual patterns even the best-intentioned

members of his audience brought with them into the movie theater. At the

end of the film, when ninety-nine viewers out of a hundred crave a little

simple emotion to carry away with them, Cassavetes stands by scenes, characters,

and relationships that won't provide condensed meanings. In a culture

addicted to easy listening and "lite" viewing, he deliberately

made it more than a little hard to read his scenes and characters. Cassavetes

refused to tame the uncertainties of life. He leaves us wonderfully uncertain

and suspended. He returns us to the ambiguities and confusions of lived

experience. We can't ultimately "figure out" Robert and Sarah

or their film.

No more than any of the previous

works, does Love Streams pose easy questions and provide comfortable

answers. It leaves us with perplexities, contradictory feelings, and doubts.

Cassavetes gives us a form of art that does not attempt to offer clarities

and resolutions, but rather tensions and unresolved mysteries. Most films

offer clarifications of life. They hand out little fictions to live by,

or at least momentarily displace the confusions associated with the experiences

we have outside of the movie theater. Cassavetes goes in the opposite

direction. He strips away fictions. He denies us intellectual distance

on experience. He forces us into our places of discomfort. He offers a

difficult form of art (though it might also be called an invigorating

one). As everything I have been arguing should suggest, the emotional

irresolution of these scenes is not something to be gotten beyond, but

to be lived into. Cassavetes knows not only that growth is painful, but

also that growth comes only from pain. Rather than trying to allay our

fears and doubts, he forces us into them. In having our easy solutions

frustrated, we may arrive at hard truths....

To read more about the limitations

of contemporary criticism, see "Sargent and Criticism" in the

Paintings section, "Capra and Criticism" in the Frank

Capra section, and "Skepticism and Faith," "Irony and

Truth," "Looking without Seeing," and other pieces in the

Academic Animadversions section. To obtain more information about

Ray Carneyís writing on contemporary criticism, click

here

This

page only contains excerpts and selected passages from Ray Carney's writing

about John Cassavetes. To obtain the complete text as well as the complete

texts of many pieces about Cassavetes that are not included on the web

site, click

here.

|