|  ....There

is never anyone to blame in Cassavetes' work. There are no villains in

his films; no good guys or bad guys. Everyone is in-between. If Lelia,

Tony, Bennie, Hughie, and the other characters in Shadows have

problems, they themselves have created them, and they themselves must

solve them. ....There

is never anyone to blame in Cassavetes' work. There are no villains in

his films; no good guys or bad guys. Everyone is in-between. If Lelia,

Tony, Bennie, Hughie, and the other characters in Shadows have

problems, they themselves have created them, and they themselves must

solve them.

In his work the problems characters

have are never outside, but within the characters themselves. In their

different ways, each of Shadows' characters is playing a role

that is false to his or her true self–trying to be something

he or she is not.

Tony wants to be a "stud;" Bennie wants to be "cool;" Hughie wants to

be the strong, protecting, older brother; Lelia wants to pretend that

race doesn't matter and that sex has no emotional consequences.

The lies that are important

in Cassavetes' films are never the ones we tell others, but those we tell

ourselves. Of course, when we fool ourselves, when we are false to our

true needs and desires, we are always the last ones to realize it.

As in classic Greek drama,

each of Cassavetes' films ends with a moment of insight or self-recognition.

Characters discover something about themselves–not by thinking

but by listening to their feelings. One day they finally hear a little

voice

of discontent that may have been nagging away for years, and, if they

are lucky, wake up. Shadows ends with four recognition scenes.

Lelia, Ben, Hugh, and Rupert each realize something about how they

have been

false to themselves. Cassavetes is a very spiritual artist. All of his

work is about learning to hear that still, small voice. What is wonderful

is that he never gives up on even his most doomed characters. He is an

artist of hope–a poet of the miraculous, transforming power

of love and grace....

* * *

The

central metaphor in Shadows

involves a comparison of the "masks" we wear in public with the "faces"

we hide beneath them. Characteristic of Cassavetes' rhetorical understatement,

the image surfaces explicitly at only two points: when Ben studies a "mask"

in the Museum of Modern Art sculpture garden, and in the tilt shot framing

an African mask that precedes Lelia and Tony's post-coital conversation.

In both cases, Cassavetes' camerawork implicitly asks us to compare the

mercuriality of living expressions with the stasis of sculpted ones.

(As

a sidelight, I might add that neither of these scenes was present in

the

"improvised" version of the film. Both were added during the scripted

reshooting done two years later–suggesting that it probably

took Cassavetes himself a couple years to fully understand the meaning

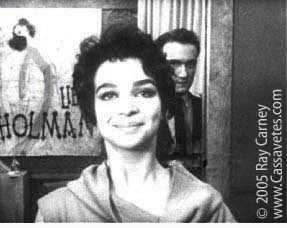

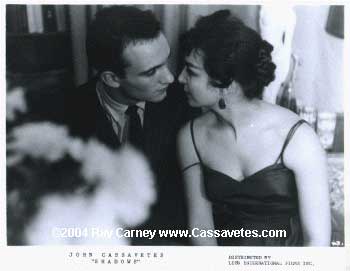

of his own work.) The

central metaphor in Shadows

involves a comparison of the "masks" we wear in public with the "faces"

we hide beneath them. Characteristic of Cassavetes' rhetorical understatement,

the image surfaces explicitly at only two points: when Ben studies a "mask"

in the Museum of Modern Art sculpture garden, and in the tilt shot framing

an African mask that precedes Lelia and Tony's post-coital conversation.

In both cases, Cassavetes' camerawork implicitly asks us to compare the

mercuriality of living expressions with the stasis of sculpted ones.

(As

a sidelight, I might add that neither of these scenes was present in

the

"improvised" version of the film. Both were added during the scripted

reshooting done two years later–suggesting that it probably

took Cassavetes himself a couple years to fully understand the meaning

of his own work.)

However, the most resonant

occurrences of masks in Shadows are not in visual images, but

in the characters' behavior. Long before Ben calls attention to the

MoMA

mask, a viewer is made aware of how he wears an even subtler and more

insidious mask–one that he is not aware of and that he can't

remove–the

mask of hipness, archness, and irony (a force within American culture

that is still clearly being felt today). He hides behind his sunglasses,

leather jacket, and beat-generation poses. Though Ben scoffs at the pretentiousness

of a literary party he attends, Cassavetes makes a viewer realize

that

he plays a role at least as hollow as that of the poseurs who babble

about

"existential psychoanalysis." His "cool-man-cool" role-playing is an

attempt to insulate himself from emotional vulnerability or involvement.

That

is why he spends his time cruising for pickups and spoiling for fights.

As long as he keeps moving from girl to girl, he knows no deep emotional

claims will be made on him or enduring commitments required. As long

as he keeps fighting, he won't have to really interact. He won't have

to

take off the mask and reveal the insecurities underneath it.

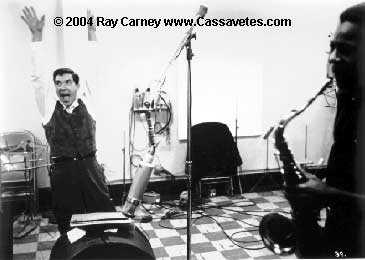

Hugh,

Lelia, and Tony are also mask-wearers, though less obviously. As a

professional jazz musician whose

career has failed to take off, Hugh has been reduced to playing clubs

full of drunks and to introducing a chorus line to get on stage at

all.

But as deeply hurt as he is by the compromises he has made, he puts on

a brave front for his brother, sister, and Rupert, who depend on him

for

both emotional and financial support. His stoical stance is one that

many of the male characters in Cassavetes' other films will adopt–a

pretense of male poise and confidence that covers up feelings of inadequacy

and

self-doubt. Lelia has found another way of masking her pain and covering

up her vulnerabilities. After making the mistake of thinking that

sex

can be free from emotional complications and being profoundly hurt by

the consequences, she goes to the other extreme, withdrawing into

a camouflaging

flirtatiousness, flamboyance, and self-dramatizing theatricality calculated

to let no one get near her emotionally. Tony is also a mask-wearer.

He

retreats from intimacy behind the role of wise male protector. He is

too busy proving to women how experienced he is, how much he knows

and feels,

ever actually to allow himself to learn or feel anything. Hugh,

Lelia, and Tony are also mask-wearers, though less obviously. As a

professional jazz musician whose

career has failed to take off, Hugh has been reduced to playing clubs

full of drunks and to introducing a chorus line to get on stage at

all.

But as deeply hurt as he is by the compromises he has made, he puts on

a brave front for his brother, sister, and Rupert, who depend on him

for

both emotional and financial support. His stoical stance is one that

many of the male characters in Cassavetes' other films will adopt–a

pretense of male poise and confidence that covers up feelings of inadequacy

and

self-doubt. Lelia has found another way of masking her pain and covering

up her vulnerabilities. After making the mistake of thinking that

sex

can be free from emotional complications and being profoundly hurt by

the consequences, she goes to the other extreme, withdrawing into

a camouflaging

flirtatiousness, flamboyance, and self-dramatizing theatricality calculated

to let no one get near her emotionally. Tony is also a mask-wearer.

He

retreats from intimacy behind the role of wise male protector. He is

too busy proving to women how experienced he is, how much he knows

and feels,

ever actually to allow himself to learn or feel anything.

Cassavetes' understanding of

expression was an actor's. That is to say, for him, there was no essential

difference between the expressive situations of acting and of life: What

happened in one had its equivalent in the other. The artistic impoverishments

of timid or derivative forms of acting were inextricably linked in his

imagination with the disappointments of timid or derivative ways of living;

and, conversely, the aesthetic excitements and challenges of original

and brave acting were indistinguishable from the stimulations of original

and brave living.

He understood that people

wear masks in life and hide behind dependable roles in their relationships

with others for the same reasons actors do in their performances. It

is safer and more comfortable to play a fixed role than to make oneself

genuinely

responsive to the shocks and jars of an open-ended relationship–on-stage

or off-. A related parallel between bad acting and bad living, in Cassavetes'

view of it, is the desire to "star" rather than interact. Like Jack Nicholson,

Meryl Streep, and Harvey Keitel (three of America's most over-rated

actors),

we want others to respond to our emotional pacings and emphases, rather

than making ourselves responsive to them.

Ben's

beat generation costume (black leather jacket and sunglasses even

indoors and at night), affectless

tones (disillusioned, self-pitying, and already burnt-out at age 21–"Maybe

I'll join a little group in Vegas"), and Tom-catting (forever on the

prowl for a different girl every night) allow him to be the long-running

star

of his own one-man road show, but by the same virtue, they deny him possibilities

of emotional openness to or involvement with anyone other than himself

and his own problems. Lelia's self-centered self-dramatizations are more

inventive and interesting than Ben's monotone posturing, but ultimately

no different from it. Her Garboism (or Meryl Streepism) cuts her off

from experience in the same way his Brandoism does: it gives her star

billing

in a repertory company in which she plays the most important part, lets

no one upstage her, steal her scenes, or get within a mile of her emotionally. Ben's

beat generation costume (black leather jacket and sunglasses even

indoors and at night), affectless

tones (disillusioned, self-pitying, and already burnt-out at age 21–"Maybe

I'll join a little group in Vegas"), and Tom-catting (forever on the

prowl for a different girl every night) allow him to be the long-running

star

of his own one-man road show, but by the same virtue, they deny him possibilities

of emotional openness to or involvement with anyone other than himself

and his own problems. Lelia's self-centered self-dramatizations are more

inventive and interesting than Ben's monotone posturing, but ultimately

no different from it. Her Garboism (or Meryl Streepism) cuts her off

from experience in the same way his Brandoism does: it gives her star

billing

in a repertory company in which she plays the most important part, lets

no one upstage her, steal her scenes, or get within a mile of her emotionally.

Like bad actors, in their

different ways, Ben, Lelia, Hugh, Rupert, and Tony attempt to get

their acts together

and work up routines so good they won't ever have to depart from them.

Everything Cassavetes stood for was opposed to this sense of "canning"

the self or its performances. He saw life and acting not as about getting

your part down so pat that you'd never have to think on your feet, but

as a process of opening yourself up so completely you could never say

in advance where you were going to come out or what you might discover

along the way. To invoke Cassavetes' momentary alter ego–you

must

"break your pattern."

The

issue goes beyond being open or closed to others; what matters is whether

one has an open or closed identity. What's really wrong with designs for

living is that they represent dead-ends for development. Cassavetes subscribes

to a state of radical ontological open-endedness, played out in acts of

continuous self-revision. The deepest problem with Ben's, Tony's, Lelia's,

and Hugh's mask-wearing and role-playing (both as actors and as characters)

is that they represent efforts to formulate fixed, finished identities.

For Cassavetes, to be finished in this way is to be finished in every

other as well. At its best and most exciting, the self is not only unformulated,

but unformulatable. You can never close up shop on who you are. Living

begins at the very moment you dare to leave the scripts of life behind

and begin to improvise on the margins.... The

issue goes beyond being open or closed to others; what matters is whether

one has an open or closed identity. What's really wrong with designs for

living is that they represent dead-ends for development. Cassavetes subscribes

to a state of radical ontological open-endedness, played out in acts of

continuous self-revision. The deepest problem with Ben's, Tony's, Lelia's,

and Hugh's mask-wearing and role-playing (both as actors and as characters)

is that they represent efforts to formulate fixed, finished identities.

For Cassavetes, to be finished in this way is to be finished in every

other as well. At its best and most exciting, the self is not only unformulated,

but unformulatable. You can never close up shop on who you are. Living

begins at the very moment you dare to leave the scripts of life behind

and begin to improvise on the margins....

To read another essay on the

relation of Shadows to Beat Generation filmmaking and Robert Frank's

Pull My Daisy, look in the Beat Movement section or click

here or here.

This

page only contains excerpts and selected passages from Ray Carney's writing

about John Cassavetes. To obtain the complete text as well as the complete

texts of many pieces about Cassavetes that are not included on the web

site, click

here.

|