|

....Most

films foster two fundamental illusions about experience: namely, that

things happen to us, and that what matters is what we do back to them.

Characters have enemies or are given obstacles to deal with. Cassavetes

understands that our only real enemy is ourselves. There are no villains

and never anyone to blame in his work. There are no obstacles to overcome,

except the ones we impose on ourselves. ....Most

films foster two fundamental illusions about experience: namely, that

things happen to us, and that what matters is what we do back to them.

Characters have enemies or are given obstacles to deal with. Cassavetes

understands that our only real enemy is ourselves. There are no villains

and never anyone to blame in his work. There are no obstacles to overcome,

except the ones we impose on ourselves.

The other kind of movie gives

characters problems to solve. Cassavetes tells us that we create all

of

our own problems. Character itself is the only important problem. There

is no need to add anything else; it is already more than enough for

someone

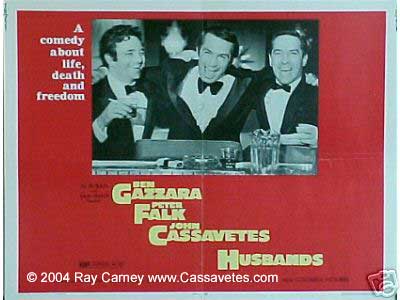

to deal with. The events in Husbands are not generated by anything

that Archie, Harry, and Gus do, but by what they are.

In Cassavetes' work, personality is plot; behavior is narrative. Living

does

not involve doing anything but being something – a

much harder task for both a character and a viewer to deal with.

Mainstream works employ a question-answer

form of presentation that allows viewers to participate along with the

character in the achievement of a goal or attainment of a solution. Scenes

ask questions or pose dilemmas that, for both the character and the viewer,

subsequent scenes answer or resolve. The reason films are organized this

way is obvious: It makes things much easier on viewers by limiting and

focusing what they need to pay attention to. Progress or lack of it is

easy to keep track of. At any one moment, the viewer and character know

almost exactly where they are and how far they have yet to go.

One

of the things that drives viewers crazy is that Cassavetes doesn't

provide this sort of ontological

road map for development. He doesn't organize his films around problems

to solve. Scenes don't pose questions which subsequent scenes answer.

Characters don't have particular things to do, or goals to achieve. It

would be a lot easier if Cassavetes made the other kind of movie.

If Richard,

Maria, Cosmo, Myrtle, and Robert had specific problems to solve or goals

to attain – or, in Husbands, if Harry, Archie, and Gus

did – the

viewer would know what he should pay attention to in each scene and,

to some extent, how to understand it. Instead, it is as if the viewer

has

to pay attention to everything. To the maximum degree possible, experience

is encountered "whole" – in an unanalyzed, unedited,

unglossed form. One

of the things that drives viewers crazy is that Cassavetes doesn't

provide this sort of ontological

road map for development. He doesn't organize his films around problems

to solve. Scenes don't pose questions which subsequent scenes answer.

Characters don't have particular things to do, or goals to achieve. It

would be a lot easier if Cassavetes made the other kind of movie.

If Richard,

Maria, Cosmo, Myrtle, and Robert had specific problems to solve or goals

to attain – or, in Husbands, if Harry, Archie, and Gus

did – the

viewer would know what he should pay attention to in each scene and,

to some extent, how to understand it. Instead, it is as if the viewer

has

to pay attention to everything. To the maximum degree possible, experience

is encountered "whole" – in an unanalyzed, unedited,

unglossed form.

Audiences sit through a movie

like Husbands waiting for a challenge to be posed, a course

of action to be embarked on, and, in the end, a solution to be achieved

(or

not achieved) – and get frustrated when the film doesn't play the

Hollywood game. The only "problem" Harry, Archie, and Gus deal

with is an emotional one involving their doubts about who they are and

what they

want out of life. The difference between this sort of problem and the

other kind is, of course, that you don't necessarily even know you have

it, let alone being able to tell if you are getting anywhere in terms

of solving it.

If these characters even knew

they were confused, they wouldn't really be as confused as they are. As

Cassavetes once put it to me: "The problem with most movies is that

people know what's wrong. What happens in life is you can't sleep at night,

or are unhappy, but don't know why." Nick, Cosmo, and Robert all

illustrate the point. They think they are OK, and keep insisting on it

to everyone they meet, even as they get into ever deeper emotional water.

To paraphrase a Stevie Smith poem, they think they are waving, while they

are really drowning. If these characters even knew

they were confused, they wouldn't really be as confused as they are. As

Cassavetes once put it to me: "The problem with most movies is that

people know what's wrong. What happens in life is you can't sleep at night,

or are unhappy, but don't know why." Nick, Cosmo, and Robert all

illustrate the point. They think they are OK, and keep insisting on it

to everyone they meet, even as they get into ever deeper emotional water.

To paraphrase a Stevie Smith poem, they think they are waving, while they

are really drowning.

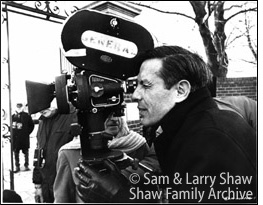

Like George Balanchine (who

used to tell his ballerinas "perfect is boring"), Cassavetes

was, at his greatest, a choreographer not of unworldly grace and grandeur,

but of the sorts of awkwardness, hesitation, and uncertainty that most

of the greatest moments in real life consist of. That may make art seem

all too easy, but it took Cassavetes multiple drafts of his scripts,

hours

of rehearsals, and repeated takes to generate the impression of muddlement

he was after. The impression of casualness takes a lot of discipline

to

achieve. It took labor to make it look effortless. Tristram Powell's

BBC documentary about the creation of the film (which has unfortunately

only

been shown in an edited version in this country) shows the filmmaker

working, working, working with his actors on timings, pacings, shifts

of beats.

To make it look easy, he has to make it hard on them, preventing things

from getting too clear or direct. He worked, as he called it, "to

get the literary quality out" of his scenes – to prevent

his characters from being too articulate, their interactions from becoming

too linear,

their emotional line from being too clean. For Cassavetes, truth is always

dirty. When we dance in the dark, we inevitably step on toes.

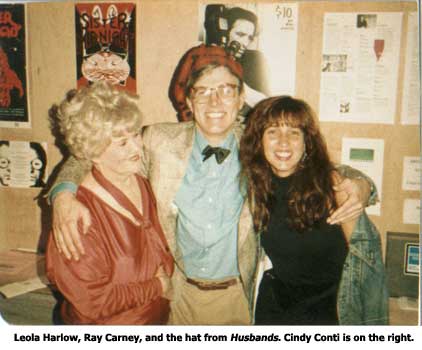

The

only entire scene in Husbands that was not scripted in advance

was the singing contest, including the long interchange with Leola Harlow

(the woman wearing the red tam-o'shanter who sings "It was just a

little love affair"). But there was a method to the apparent madness

of going off-book for this particular interchange. Harlow told me that

when Cassavetes, Falk, and Gazzara swarmed all over her about her singing,

she didn't realize it was part of the scene. She thought that she was

being directed to change her performance and that her performance as an

actress was genuinely being rebuked. She was genuinely hurt and upset

by the criticism. In short, Cassavetes used the unscriptedness of the

moment to get emotions that he could not have gotten otherwise. The

only entire scene in Husbands that was not scripted in advance

was the singing contest, including the long interchange with Leola Harlow

(the woman wearing the red tam-o'shanter who sings "It was just a

little love affair"). But there was a method to the apparent madness

of going off-book for this particular interchange. Harlow told me that

when Cassavetes, Falk, and Gazzara swarmed all over her about her singing,

she didn't realize it was part of the scene. She thought that she was

being directed to change her performance and that her performance as an

actress was genuinely being rebuked. She was genuinely hurt and upset

by the criticism. In short, Cassavetes used the unscriptedness of the

moment to get emotions that he could not have gotten otherwise.

The irony was that Cassavetes

succeeded so well in depicting the rawness of unformulated feeling

that

he was thought not to have prepared properly. He was so adept at capturing

the flowingness of improvised lives that reviewers assumed that his

actors

were improvising. There is a difference between the depiction of disorganization

and making a disorganized film. Husbands is a study of confusion – a

very different thing from being confused....

This page only

contains excerpts and selected passages from Ray Carney's writing about

John Cassavetes. To obtain the complete text as well as the complete texts

of many pieces about Cassavetes that are not included on the web site,

click

here.

|