|

This

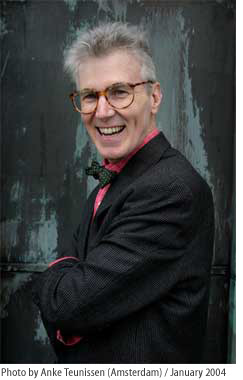

page contains an excerpt from a lengthy interview with Ray Carney. In

the selection below, he discusses the attitude of intellectuals towards

film. The complete interview from which this excerpt is taken is available

in a new packet titled What's Wrong with Film Teaching, Criticism,

and Reviewing—And How to Do It Right. For more information about

Ray Carney's writing on independent film, including information about

how to obtain this interview and two other packets of interviews in which

he gives his views on film, criticism, teaching, the life of a writer,

and the path of the artist, click

here.

“A

herd of independent minds”

Or, Intellectuals are the last to know

Click

here for best printing of text

Interviewer:

Last time, we were discussing the limitations of academic film criticism.

I wanted to begin this session more positively, by asking if you could

give me a list of “good guy” critics, magazines, and journals.

Do you have any critic-heroes?

Carney: Henry

James, D.H. Lawrence, and William James.

Interviewer:

They're not critics. You've named two novelists and a philosopher! Interviewer:

They're not critics. You've named two novelists and a philosopher!

Carney: James's

and Lawrence's essays – James's are available in two Library

of America volumes and Lawrence's in two fat paperbacks

called Phoenix I and

II – are the most brilliant criticism of the last hundred

years. And William James's Pluralistic Universe, Some Problems in

Philosophy,

and the posthumous Essays in Radical Empiricism – they're

all available in a Library of America volume – open the

door to a new way of thinking about art – and life. William

James is particularly brilliant about the temporality of meaning.

Interviewer:

Are there any real critics you admire?

Carney: F.R. Leavis,

B.H. Haggin, Jack Flam, and Seymour Slive.

Interviewer:

Who are they?

Carney: Haggin

wrote about music and dance; Leavis edited a great literary magazine – Scrutiny – and

wrote a lot of wonderful essays and books. Flam has published a few

books

and writes for the New York Review of Books. Slive is an art critic

who did for Frans Hals what I would like to think I am doing for Cassavetes.

Oh, I should also mention my former teacher, Dick Poirier. His work and

his teaching have been an inspiration to me. He also edited a journal

called Raritan that was quite wonderful.

Interviewer:

Have any of them written about American independent film?

Carney: Well,

Leavis is long gone. Scrutiny stopped publishing fifty years ago.

And Poirier no longer edits Raritan. He retired and turned it over

to someone else last year. And the other two only write about fine art.

So the answer is no. But the question is a good one. That's the problem.

There are no really serious living critics interested in film. Only mediocre

ones. And complete hacks.

Interviewer:

You've already described at length the limitations film professors labor

under. How about finding allies among English professors, philosophy professors,

or other academics in the humanities. Lots of them include film in their

courses. Many of them write about film.

Carney: That

was actually my dream when I started out. At the beginning of my academic

career, I looked everywhere for other faculty members who took film seriously,

but I couldn't find any! My initial thought was exactly what you said – that

I could turn to the high-culture types, the English and art and philosophy

professors, to find allies who would bring the same values to film study

that they did to the study of other arts. I thought if we got together

we could change the history of film appreciation. But the problem is

most American intellectuals are captive to the same low-brow notions

of “the

movies” as film scholars are. I find myself alone in this crusade

for film art. If one really major voice, I mean a really deep thinker – not

some journalist, not some jargon-addled, footnote-happy film professor – started

championing art film, it could change everything. But I don't see

any

likely candidates.

Interviewer:

What do you mean? How can that be? Interviewer:

What do you mean? How can that be?

Carney: Humanities

professors may teach film or write about film, but they don't treat

it

as being fully equal to other high arts – fiction or painting

or poetry. Stanley Cavell is a former teacher of mine and a professor

of philosophy

at Harvard who has written a lot about high-brow literature: Thoreau,

Emerson, Shakespeare. And he writes a lot about film. But guess what

films

he picks to discuss? Old Hollywood movies! Cary Grant and Irene Dunne

and Bette Davis movies. Geoffrey O'Brien is another scholar with literary

credentials who writes about film in The New York Review of Books.

So what does he write about? Steven Spielberg's AI and Spiderman.

Morris Dickstein is another very smart cookie who writes about film

in

Partisan Review. His taste is a step up from O'Brien's, but only

a step. Scorsese's or Welles's work defines the boundaries of his vision

of art cinema. On paper, Poirier would seem to be the ideal combination

of someone who understands the rigor of artistic expression, yet is

open

to challenging, contemporary work. He cut his critical teeth in the sixties

and seventies crusading for challenging writing – Nabokov,

Mailer, Pynchon, and Stone. But when it comes to film, his mind is

indistinguishable

from Vincent Canby's. I asked him once who was his idea of a great director?

He said Alfred Hitchcock.

Interviewer:

You're saying Hitchcock is the wrong answer?

Carney: No I'm

saying he's the right answer, but that's just the problem. If you

ask

who is the greatest American director, Hitchcock is the officially approved,

correct, safe, obvious answer. The answer six out of ten American

hack

reviewers would give – the other four would say Welles – showing

that whoever gives it has not given any real thought to the question.

When I once asked

Poirier what he thought about Cassavetes, he didn't seem to know who he

was, and replied by saying a friend of his loved Mean Streets.

Raritan was a terrific literary journal, but it only ran a few

pieces on film, and they were downright embarrassing.

These examples

are not exceptions. Art film is just not on the high-culture intellectual

map. You can be one of the leading American intellectuals of the second

half of the twentieth-century, and never have seen a Cassavetes movie,

a Rappaport movie, a Morrissey movie, a Kramer movie. And not be ashamed

to admit it!

And don't forget,

I am talking about the “good guys,” the members of the high-culture

elite who profess to take film seriously. There are lots of others, like

Hilton Kramer and Roger Kimbell and Gertrude Himmelfarb, who don't admit

that any film can be artistically interesting.

I had a surreal

experience a few years ago that depressingly summarized the situation.

I don't want to name names, but suffice it to say the editor of one of

the most prestigious literary magazines in the United States invited

me

to lunch and offered me the opportunity to become the magazine's regular

film critic. The offer caught me completely by surprise. I was bowled

over – flattered and honored and amazed – and

told him so. But the fizz went out of the champagne pretty quickly. He

went on

to tell me that

he had picked me because, based on my “Canby caper” [a New

Republic cover story that is available elsewhere on this site] and

several other polemical pieces I had written [for Raritan, the

Baffler, and The Chicago Review]. He said he thought I

was the best person in America to deflate the claims made for the importance

of films like Blue Velvet, The Cook, The Thief, and

his Wife..., Natural Born Killers, Pulp Fiction, L.A.

Confidential, Eyes Wide Shut, and others. He said that's what he

looked for me to do in the pages of the magazine. I would be his Hollywood

hit-man.

I told him I

shared his opinion about these works and about the fatuousness of

the critics

who championed them, but I had no desire to become another John Simon.

I told him I also wanted to celebrate overlooked or forgotten American

masterworks. There was a long pause. The editor gave me a puzzled look.

He obviously didn't know there was any such beast as an American masterwork

in film! He didn't have the category. He drew himself up to his full

height and in his best Brahmin manner said: “Name one.” I

forget exactly what titles I named but I rattled off seven or eight

titles – something

like Crazy Quilt, Wanda, Ice, A Woman Under the Influence, Killer

of Sheep, What Happened Was, and Safe. He sniffed that he

hadn't heard of any of them. Do you get the picture? He didn't say it

humbly

but more as if it proved that they couldn't be that great. It

was one of those moments that only occurs a few times in life, because

in

a heartbeat the whole tone of our conversation changed. He decided that

I might be just as crazy as those other reviewers. I actually took film

seriously! I thought it was an important contemporary art! I was talking

about “masterworks”! The only difference between me and the

crackpots was that I had a different list of titles!

Interviewer:

What happened? Interviewer:

What happened?

Carney: Like I

said, everything shifted. We politely talked some more and agreed that

someone else might be better for the job he wanted done. That conversation

was a turning point for me. It helped me realize that the intellectuals

would not be my allies in this battle.

Interviewer:

That's such a weird encounter. Why do you think they don't appreciate

film as art?

Carney: There

are a lot of reasons. To start off, you have to remember that people like

Cavell and Dickstein and Poirier and this editor get their information

about film from the same sources they get their other cultural news: The

New York Times, The New Yorker, The New York Review of

Books, and similar places. They don't even hear about works

of genius in American film, let alone read favorable reviews of them,

or get a chance to see them. They don't know that the kinds of cinematic

experiences I am talking about even exist. There's a book to be written

about effect of The New York Times on American taste.

Interviewer:

What do you mean?

Carney: I mean

it's friggin' unbelieveable the influence it has on intellectuals!

You

read accounts of how closed-off and incestuous French intellectual life

was at the turn of the century – or of how every idea

in the post-war years in Paris originated in one of three intellectual

journals. And you're

supposed to draw the conclusion that America is different. Well it's

not.

The New York Times is American high culture for most intellectuals.

If it's in The Times, it matters. If it isn't, it doesn't. In

fact, you don't have to do anything but write for The Times to

be categorized as an intellectual in the minds of most editors and

professors.

Interviewer:

But doesn't The Times have a lot of intellectuals writing for it?

Carney: Not real

intellectuals. The journalistic version. The kind of “celebrity

thinkers”

that Charlie Rose fawns over most nights. The Times is less the

print version of a university, than of an intellectual fashion show.

There

are no really challenging, controversial pieces in The Times.

You discover that every time you read an article about anything you

really

know a lot about – organic chemistry, geology, Bach, Shakespeare,

Picasso, economics, whatever. You see how shallow and partial the treatment

of

it is. But since every other newspaper is even more dumbed down, and

most people don't know the real story on all of the subjects they include

(in

the this case the shabbiness of their coverage of film), The Times

looks like it's written by Einstein. But only in comparison. It's

just a newspaper, and not a very deep one, but in our cultural wasteland,

it is treated like it was Scrutiny or Science.

Interviewer:

What's the basis for saying that intellectuals take The Times that

seriously? Interviewer:

What's the basis for saying that intellectuals take The Times that

seriously?

Carney: Twenty

years of dinner party conversations. Twenty years of cocktail party chit-chat.

If you tell someone at one of these events that you haven't read an “important”

article they treat you like a student who didn't do his homework. And

if you let your subscription lapse out of indifference or disgust, be

sure not to tell a humanities professor. He'll never take you seriously

again. I speak from experience! [Laughing]

Interviewer: But isn't all

of this pretty trivial? Even if you are right that academics take The

Times too seriously, it doesn't really make much difference one way

or the other. It's just a newspaper. Something they read at breakfast.

Carney: No. That's my point.

That it isn't just something they read at breakfast. I am talking

about

a very serious distortion in intellectual values that has all sorts of

important ramifications. We live in a culture of celebrity, where

people

are famous for being famous, and there are lots of important consequences

to that state of affairs. Some of the consequences of our culture

of celebrity

play out in terms of our political system – who runs for

office and gets votes. Some of the consequences of the culture of celebrity

play

out in terms of the arts and entertainment system – what

movies are made, who gets to act in them, and how they get to be popular.

And some

of the consequences—the ones I am talking about right now – play

out in terms of the critical system in the way journalism distorts intellectual

values. I am using The Times as an example of that distortion.

But the problem I am describing is not confined to The Times. And

the consequences reach far beyond the newspaper or the breakfast table.

Intellectual values are distorted. Important things are lost sight of.

Interviewer: Can you explain

in more detail what the consequences are?

Carney: Well, I have already

given you some. In my conversation with that editor, when he didn't

know

that there could be film that was not part of the pop culture system,

that was a consequence. When certain kinds of artistic expression,

say

the films of Jay Rosenblatt or Mark Rappaport, are systematically excluded

from consideration in organs like The Times or The New York

Review of Books, they fall off the high culture radar scope.

For all intents and purposes, they cease to exist intellectually.

Oh, the objects

still exist – the films and tapes – but if they are

not discussed and viewed and made part of the larger cultural discourse,

they have

no

effect. Call it the John Cassavetes principle. With the possible exception

of two of his films, Faces and A Woman Under the Influence,

and them only briefly, he really didn't exist intellectually.

Interviewer: What do you

mean?

Carney: The vast majority of

his work not only wasn't appreciated and praised, it wasn't even discussed.

It wasn't on the map culturally speaking. And it still isn't!

But let me back up. I probably

shouldn't have mentioned Cassavetes' name. That only gives the wrong impression.

What I am talking about is not the neglect of a particular artist. That's

minor by comparison. I am talking about our celebrity culture, how journalists

have become part of it, and the effects of that on the way the intellectual

system is structured.

Interviewer: OK. Can you

talk about that in more detail? Interviewer: OK. Can you

talk about that in more detail?

Carney: Well, the basic situation

is that popularity displaces value judgment. Journalists and the things

they write about have become part of the celebrity culture, which means

that once someone or someone appears in The New York Times or The

New Yorker, he, she, or it is taken seriously. If someone's name appears

in the New York Times or The New Yorker a certain number

of times, that's all that it takes to constitute importance. And the people

who appear in The New York Times or The New Yorker the most

are journalists. So they are taken the most seriously. They become the

cultural definition of what it is to be a thinker. If a journalist is

merely a bit clever verbally and shows up on the breakfast table long

enough, most academics and intellectuals mistake him or her for a thinker.

No one ever asks if you are really important. Are you really

smart?

It's is not a new phenomenon.

The journalist as thinker I mean. Look at the Pauline Kael craze of a

decade or two ago. In college I remember how seriously people used to

read her New Yorker pieces. Of course there were anti-Kaelians.

But they never escaped from the hermeneutic circle. If you didn't like

Kael, you would discuss whatever Andrew Sarris wrote for the Village

Voice or the pieces Stanley Kauffmann wrote for The New Republic.

To reread any of these things now is to wonder what all the fuss was about.

There is nothing to any of them. They were the rough equivalents to the

hot television show of their era. The moral: If you simply get into enough

houses every week, and have a minimum amount of verbal flash or style,

there are hundreds of thousands of intellectuals who are willing to canonize

you. Particularly in film, the staggeringly low level of discourse makes

anyone with an IQ above 100 seem like a genius.

The consequences are everywhere.

Take the MacArthur Foundation –

Interviewer: —the “genius

award” people?

Carney: Exactly. The most prestigious

intellectual awards in America. Every year they select a small number

of artists and intellectuals to give enormous financial support to. Well,

do you know who nominates the film recipients and referees other people's

nominations? Take a guess.

Interviewer: Who?

Carney: Roger Ebert. Is that

friggin' unbelievable or what? Is it any wonder that John Sayles has gotten

a genius grant and Mark Rappaport hasn't? But it's really no different

with the Guggenheims or the Rockefellers or the McDowells or any of the

rest of them. Read through the past awards lists over the last decade

or two. If you write for The Village Voice, The New York Times,

or the New Yorker, you're in an excellent position to get a Guggenheim.

A lot better chance than if you are on the faculty of an unknown college

and write books. Is it clear how totally backward this situation is?

My understanding of being a

intellectual is that it is to be given a unique opportunity to stand just

a little outside our culture's system of hype and publicity. It is to

be someone who refuses to be pulled into the muddy undertow of advertising,

journalistic sensationalism and celebrity worship. While more or less

everyone else is paid to sell something, the academic is paid to be independent.

Or not paid. But is independent anyway. But what has happened in our culture

is the opposite. At least in film, the intellectuals line up to sell out

to the culture's values. And for the people giving out the grants and

prizes, the celebrity tail wags the intellectual dog. Our universities

are no different.

Interviewer: Where do universities

come into this?

Carney: Like the rest of intellectual

culture, they take their values from journalists and pop culture. That's

why they appoint journalists to their faculties. When they are not appointing

movie stars and Hollywood directors.

A couple weeks ago I got an

invitation to a lecture series at Harvard. Guess who was being paid to

come and speak to the students? Elvis Mitchell, the film reviewer at The

Times. A few years before that, Harvard gave Spike Lee a visiting

professorship. Two mediocrities: A journalist who sends his readers to

see Austin Powers and the remake of Star Wars and a trendy

Black filmmaker. Paid a lot of money to come to Harvard. Does that seem

as bizarre to you as it does to me? The moral of the story is that if

Mitchell and Lee are in The Times, that's all it takes to get on

the A-list in the mind of Harvard Professor Henry Louis Gates, who invited

both of them.

The university is ruled by

the same forces as the rest of the culture. Rather than standing off to

one side, most professors are busy trying to keep up with the latest trends

and fashions. That's what Gates represents. The professor as celebrity

in awe of other journalist and filmmaking celebrities and sucking up to

them. He knows that an article for the Times or the New Yorker

or an appearance on The News Hour or Charlie Rose is worth more than

a whole book published by a scholarly press, and has accordingly cut his

values to fit.

Interviewer:

Can you get back to intellectuals' attitudes toward film?

Carney: You have

to understand the high-culture bias for and against certain arts.

Opera

and ballet and art museums and symphony orchestras have an aura of respectability

that filmmakers and movie theaters never have had in our culture.

Film

is treated as pop culture, at best. Even when the professors and intellectuals

I am talking about do dabble in film, they don't take it really

seriously.

Their interest is a kind of slumming – like Igor Stravinsky

catching a show at the Cotton Club. “Oh, jazz – it's fun;

it's energetic; but it's not Beethoven.” Poirier doesn't really

think Hitchcock is equal to Wallace Stevens – but for

film, Hitchcock

is not bad. They compartmentalize their minds. They read Joyce and

Eliot

one way,

and go to a movie with a totally different mindset. If I make the mistake

of saying that I think Mikey and Nicky and Love Streams

are actually as complex as “Gerontion” and “The Dead,”

they think I'm crazy! I speak from experience. I've made that mistake

in conversations a few times, and you should see the fishy looks I've

gotten. Poirier laughed at me when I talked about Cassavetes this way

once. I don't do it any more. I haven't seen Harold Bloom's new genius

book, but I don't have to to know that it doesn't include any filmmakers.

Interviewer:

How about if you sent people like Poirier or Cavell videos of works by

Robert Kramer or Mark Rappaport? Would they see the light?

Carney: Not in

my experience. Look, I obviously can't force people to watch something

they're not interested in seeing – tying their ankles to

the legs of a chair in my living room and forcing them to sit though Milestones.

But I have tried to make the films available in various ways. I have

a

pair of 16mm projectors, and when I taught at Middlebury and Stanford

I used to invite professors over to supper and screen a film for them

afterwards. At both schools, I also used to schedule separate public

screenings of the films I was showing in my courses in the evenings

so faculty could

attend.

It was a real

education for me. In terms of the public screenings, most faculty members

weren't interested in seeing anything that did not have a famous name

connected with it. I showed lots of Chantel Ackerman and Cassavetes and

Tarkovsky movies to nearly empty auditoriums in the 1970s and early 1980s.

This was before they were names to conjure with. Even in the screenings

I held at my house, it was very hard to break these kinds of people away

from Hollywood programming. If a movie was slow, they got impatient with

it. If it was technically rough around the edges, they didn't take it

seriously. If it didn't play the same metaphoric games as most European

art filmmaking, they couldn't accept it. These men and women had Ph.D.s

in Russian or French or English literature, but that didn't mean that

they were are necessarily smart about art.

Interviewer:

But you said to me your students learn to appreciate these movies when

you show them in courses. Isn't it the same thing? Why would the professors

be slower to understand the films than the students.

Carney: Lots

of reasons! In the first place, it's hard to teach old dogs new tricks.

Professors

aren't nearly as open-minded as students. They have too much to protect

in terms of having already made up their minds about most things.

You

even see this with grad students. They are not nearly as open to new

experiences as undergrads. But the main difference is that the students

are in a course

with me and a course is different from a single screening. For me to

show someone what they are missing takes a lot more than just forcing

them

to sit though a movie. It takes a semester or two of carefully programmed,

progressive screenings – where we go from easier to more

complex artistic experiences, and I keep building on past knowledge,

developing it outward

in different directions. It takes a lot of work on my part and real openness

on their part to new ways of thinking and feeling. I do a lot of

things

to lever them out of their old ways of knowing – including

deliberately destroying a lot of the pleasure of the screening, by calling

things

out

during it, or stopping the film at a climactic moment and asking questions

about it – so that they can't just sit back and relax and

watch the movie. I am reprogramming their brains, teaching them new

sets of responses,

new things to look and listen for. Sometimes I talk all the way through

a film to prevent them from “dropping into it” even for a

minute. I have to play a lot of mind games and sprinkle a lot of fairy

dust to

keep them motivated. Students really have to put themselves in my hands,

and there may be a certain amount of resistance for the first couple

months,

but that too becomes part of the learning process – a lesson

in how we resist change and hold onto past viewing habits. But the best

ones

stay with it because as the challenges get greater, the trust and personal

bond grows. I can't do any of that when I am showing the film to a professor.

The relationship is entirely different. With twenty-year-olds who are

malleable and open to new experiences it's not that hard to orchestrate

the changes, but for someone older and more set in their ways it's much

less likely to happen.

Interviewer:

Even with someone as smart as a professor?

Carney: It's

not enough to be smart or accomplished in another intellectual pursuit.

Henry

James once said that critical perceptiveness was actually a rarer gift

than the ability to write fiction. That was a bit of an exaggeration – but

informed, independent aesthetic judgment is far from common. The

greater

the work, the more original it is and the more demands it will make.

It's not necessarily going to be obvious about what it's doing. It

can take

a lot of experience with an art form before you understand it. The metaphor

I use in my lectures – and that I used the last time

we talked – was

that the process of understanding is equivalent to learning a foreign

language – “art-speech.” It's not something

most people are born speaking. You know, it's only because people

have such

a low opinion

of “the movies” that this seems weird. If I were asking you

your views on a group of abstract expressionist paintings or a piece

of

contemporary symphonic music, it wouldn't automatically be assumed that

you could offer an informed critical judgment. You have to have a lot

of experience – with both life and art. It's only Hollywood movies

that you don't have to know anything to understand. In fact, if you

know

anything about anything, it gets in the way of understanding them!

I read an interview

with Howard Zinn the other day. He's a major twentieth-century social

historian. Very smart guy. The interviewer asked him what he thought of

Hollywood and he said he really liked Oliver Stone's work. He thought

Salvator, Fourth of July, and Wall Street were great

movies! I almost fell off my chair. But after I thought about it for a

minute I realized his answer wasn't that surprising. There are many books

where American historians name their favorite films and they are full

of junky Hollywood movies. I've never seen Ice or Milestones

or Human Remains mentioned by any history professor.

Interviewer:

Why did Zinn like Wall Street?

Carney: He didn't

say, but it's not hard to figure out. From Zinn's point of view, if a

film has a little bit of “socially relevant” content and an

“anti-establishment” message, it's a good movie. It's about

the level of analysis of a high school student. Or of the New York

Times or National Public Radio. Why do you think sentimental dreck

like The Believer gets praised? In terms of this issue, I'm on

Sam Goldwyn's side when he said if you want to send a message, use Western

Union.

I don't mean

to pick on historians. This applies to every group. What is it Joyce

says

in Finnegan's Wake? “We wipe our glosses with what we know.”

For literary critics, a movie is good if it has clever dialogue or is

a faithful adaptation. It's no different from why multiculturalists

judge

a film in terms of how many minority characters are in it or what their

income level is, why Jewish viewers like Schindler's List, World

War II vets like Saving Private Ryan, teenage girls like Titanic,

and teenage boys like The Matrix. It's identity politics. People

enjoy seeing themselves and their own views represented – not

their real selves and views of course, but a flattering, idealized

version of

them. It's not a terribly sophisticated view of what makes great art.

Yet how many times do you hear something like “Holocaust survivors

said that Spielberg's movie was accurate” invoked as proof

that Schindler's

List is a great movie?

Interviewer:

What should they be paying attention to – if

not to those things?

Carney: Style.

Form. Structure. Narrative organization. Content is the least important

part of a work. If you take the content away from Wall Street and

look at the emotional structure and form, you have a movie organized

around

personal competition and clashes of will punctuated by brief sentimental,

meditative interludes. If you look at the form and not the content,

it's

obvious that Wall Street is not a radical critique of anything.

It's an affirmation of soap opera melodramatics – another

trite, conservative Hollywood movie that glorifies egoistic assertiveness.

Not only on Wall

Street – that's trivial. But in the construction of its

scenes, its acting, and its camerawork and editing. Michael Douglas and

Charlie

Sheen

have sold their souls to fakery and hucksterdom in their performances

as much as the characters they play have sold themselves to salesmanship.

The conman trickery and showboating in the form of the acting negates

every atom of the films' allegedly enlightened content.

To switch to another

director, the costume-drama literariness of Ang Lee's novelistic adaptations

undoes everything the novels his work are based on attempt to do. The

boy's book moral structure of Spielberg's work is far more important than

the events or characters in it.

Interviewer:

Please don't take this as a hostile question, but if someone accepts your

view of these films, it inevitably raises the question of why they are

liked by so many people? Why doesn't everyone see their shortcomings?

If you are saying that they are over-rated, how do they get to be admired

so much?

Carney: I've

often thought of writing a book on the history of taste – you

know, how various figures and movements do or do not make it onto the “A-list.”

Most of the reasons why a work becomes known are completely unrelated

to its ultimate importance. There are lots of reasons a film gets to

be

famous. Many of them come down to plugging into some sort of popular

formula or recipe or cliché. The Coen bothers are popular with

critics because of their smart-ass attitude. The cynicism of their world

view.

Their clever visual tricks and jokes. Other films become popular because

they plug into emotional clichés – the save-the-world thrills

of The Matrix for the boys or the romantic sentimentality of Titanic

for the girls. Other films push thematic hot-buttons –Thelma

and Louise

was treated as some kind of feminist tract. Spike Lee's early work

presented itself as the first frank treatment of race in all of Hollywood.

And on and on it goes.

And once the

process of overvaluing something – however trashy it

may be – begins, it

perpetuates itself. Like they say about celebrities, movies get famous

for being famous. There are dozens of movies every year that people

go

to just because they are well-known. The hype takes on a momentum of

its own. You see it in past values and in present ones. Gone with

the Wind,

The Godfather, 2001, and Star Wars are really very

ordinary movies. But they have accumulated such an aura that they will

probably continue to appear on the top one hundred lists for the next

hundred years. There are plenty of directors who owe their whole careers

to contemporary hype – Spielberg of course, Oliver Stone,

Spike Lee, David Lynch. Every movie they make is guaranteed an enormous

amount

of

critical attention, no matter how silly it is.

Things may sort

themselves out in eternity, but we don't live in heaven. We live in

a

media pressure cooker. Twenty years from now Blue Velvet, Pulp

Fiction, and Mulholland Drive may be recognized for what

they were all along – rather dreadful, soulless fashion

show movies –

go through the reviews that were written in the first year of their release.

You would have thought the critics were describing the Sistine Chapel.

It's like the stock market. By the time the inevitable correction occurs,

every one who invested in the hot IPO has moved on to another overrated

hot IPO.

Interviewer:

You compare artistic values to Wall Street stock prices?

Carney: Artistic

valuation is a very fluid thing. The opinions are written in water. To

someone outside the arts world, the list of “great” films, plays,

paintings, books may seem solid and eternal; but anyone inside the system

knows that the “canon” is like an enormous, never-ending highway

project. New tunnels from one point to another are continuously being

opened, new extensions in certain directions and contractions in others

are constantly taking place. And not just in film. Shifts in valuation,

even complete reversals of judgment are constantly taking place. Clive

Bell's dismissal of Sargent stood for fifty years. Now Sargent is recognized

as a major American painter. Fifty years ago jazz wasn't academically

respectable music and D.H. Lawrence wasn't taken seriously as a writer.

Robert Frost was regarded as the equivalent of Norman Rockwell until the

nineteen seventies.

My point is that

there are just as many errors of judgment, just as many under-rated or

over-rated works today as there were in the past. Lots of Sargents. Lots

of jazz. Lots of D.H. Lawrences and Robert Frost's. The fallacy is to

think that we're so smart because the critics before us were so dumb.

The next Cassavetes will be ignored or misunderstood just as much as the

last one was.

Interviewer:

But surely great art stands out from the ordinary.

Carney: Usually

the only way it stands out is by confusing us. By being different

from

what we expect. The list of great art at any given time is just the consensus

opinion of a bunch of critics and reviewers, a group of very fallible

people with all sorts of cultural and intellectual biases. All of them

captive to the same trends and fashions as the rest of the culture – liberal

guilt that predisposes them to think that works created by gays,

women,

and blacks are more important than works created by white men; beliefs

in diversity and multiculturalism (as long as it doesn't force them

to

re-think their own lives); a tendency to be taken in by flash and cleverness.

Just like in the stock market, lots of mediocre things are hyped

and over-valued

and lots of wonderful things take a beating because they are not in fashion.

Take Citizen

Kane as an example. It's been at the tippy-top of top ten lists

for decades. OK. I'll concede that it's better than ninety-percent

of the

other movies of the period or since. But that's not saying a whole lot,

and it certainly doesn't qualify it for artistic canonization.

Why is

it so highly esteemed? It's not hard to tick off a half-dozen reasons.

Let me count the ways: First, it's admired by intellectuals for

the same

reason Zinn admires Wall Street. It has a politically and spiritually

“correct” message – “Wealth doesn't buy happiness.”

Second, the camera work and editing are masterful and virtuousic. They

proclaim that the film is “well-made,” and that a lot of thought

and care went into crafting it. Elegance and style are always in a

work's

favor. Third, it has a mystery story structure. I don't mean merely the

mystery that the film declares itself to be about – what

Rosebud means – but

the larger mystery that the film creates with its fragmented, unchronological

narrative about what particular scenes and shots mean. Kane gives

an viewer the challenge and the satisfaction that he is solving a

narrative

puzzle. Intellectuals love that. It gives them something to do while

they watch and flatters their intelligence when they figure things

out. Fourth,

there is the effect of Welles' symbolic/metaphoric style, which freights

virtually every object, lighting effect, and musical orchestration

with

a symbolic, spiritual meaning. [Doing a voice:] “Ah, the No Trespassing

sign. Don't you see? It's not just a sign. It has a spiritual

meaning. How deep.” Intellectuals love this sort of thing.

Fifth, there is the literariness of the dialogue, and the “cleverness”

of the visual and acoustic effects and narrative structure. That's the

intellectual's version of what art is about. They like Woody Allen for

the same reason! I could go on, but I hope the point is clear. In my

view,

Kane doesn't represent profundity, but the appearance of

profundity. It's a Superbowl halftime show for intellectuals—shallow

flashiness, ostentatious trickiness, and mystery-mongering. These kinds

of stylistic razzle-dazzle-effects – which momentarily resist understanding

but with the least little bit of pressure yield up their secrets – are

most critics' idea of great art. Kane is not a bad film, just

a shallow one. It is overrated because its qualities are in fashion.

I'll

give you this much: It's entertaining. It's fun. But it's not great art.

The mysteries of real art are a lot deeper than this and they don't

yield

their secrets so easily or quickly.

Interviewer:

I can understand that fashion rules the box office or what gets onto

Entertainment Tonight or Extra!, but it's very hard for me

to believe that what is included in college courses is determined in the

same way.

Carney: What's

taught or not taught is almost entirely a matter of fashion!

It's just a slightly different set of fashions – intellectual

ones – rather

than pop culture ones – though the two systems overlap at

many points. Look at the Lynch, Tarantino, and Coen brothers' crazes.

There is virtually

no difference between the popular culture and the academic assessments.

Professors are only people. They are influenced by what they read in

the

paper or see on TV or hear their friends talking about just as much as

the lowliest freshman is.

The main difference

between the academy and the media is that the academy is much less

responsive to new ideas than the media. Professors are the last to learn

new things. There's tremendous inertia in the academy. I'll give you an

example: As far as I can tell, popular culture has more or less moved

beyond Hitchcock. Students today have little knowledge of or interest

in his work; but it will be a hundred years before the UCLA film program

stops teaching him as one of its central offerings. In fact, come to think

of it, I don't think they are allowed to drop his films since they

made some kind of deal with his daughter to teach them forever if she

would give them a big donation. Talk about the university as supermarket!

Spielberg and Stone will be buying shelf space for their products next.

Maybe they already have.

There's lots

of lip-service paid to the intellectual “free marketplace,” but

the university is a very imperfect market for new ideas compared to

an

economic one. As a film professor, you don't get your book published

or your paper accepted at a conference if your ideas are too different

from

the accepted ones – and you don't get promoted if you don't

publish and deliver papers. The stock market is actually a more responsive

system.

Notions of what matters in film change a lot slower than the value of

stocks. The more original the work or your approach to it, the more

resistance

you're going to meet with from critics and audiences committed to the

ideas of the last generation.

Look at recent

history. Leaf through the indexes of the supposedly most advanced

academic

journals that covered film between 1970 and 2000 – Critical

Inquiry,

October, Representations, Wide Angle, Cinema Journal.

Tally up how many articles mention Hitchcock and Welles and Lynch in

one

column; and how many mention the work of Morris Engel, Shirley Clarke,

John Korty, Barbara Loden, Robert Kramer, Mark Rappaport, or Elaine

May

in another. Or let's simplify it, look for writing about Cassavetes.

You don't even have to limit yourself to those journals. As far as I

can tell,

not counting my own work, there was not a single serious scholarly essay

published anywhere about Cassavetes in his lifetime in English. A few

magazine articles, but nothing in a real intellectual journal. The only

reason any of this matters is that nothing changes. It is still going

on with the current Cassavetes and it will go on with the one after that.

Intellectuals are the last to know. They'll have to wait for it to appear

in The Times.

This

page contains an excerpt from a lengthy interview with Ray Carney. In

the selection above, he discusses the attitude of intellectuals towards

film. The complete interview from which this excerpt is taken is available

in a new packet titled What's Wrong with Film Teaching, Criticism,

and Reviewing—And How to Do It Right. For more information about

Ray Carney's writing on independent film, including information about

how to obtain this interview and two other packets of interviews in which

he gives his views on film, criticism, teaching, the life of a writer,

and the path of the artist, click

here.

|