Excerpts

from Ray Carney’s award–winning 1990 Kenyon Review John

Cassavetes memorial

essay. This piece was co–winner of the “Best Essay of the Year by

an Younger Author Award.” Only the beginning and the conclusion of the

essay are printed here. To obtain the complete essay, purchase Ray

Carney’s John Cassavetes: Collected

Essays packet.

Click

here for best printing of text

AMERICAN

HEROISM

Life

is a series of surprises and would not be worth the taking or keeping if it were

not. . . . Onward and ever onward. . . . the coming only is sacred. . . . Nothing

is secure but life, transition, the energizing spirit. — Ralph

Waldo Emerson

We

realize this life as something always off its balance, something in

transition, something that shoots out of a darkness through a dawn into a

brightness that we feel to be the dawn fulfilled. — William

James

John Cassavetes completed eleven

films prior to his death last year in 1989. While three (Too Late Blues, A Child Is Waiting,

and Gloria)

were studio co-productions which are not really representative because of compromises

were required during their

production, the other eight (Shadows, Faces, Husbands, Minnie and

Moskowitz, A Woman Under the

Influence, The Killing of a Chinese

Bookie, Opening Night, and Love Streams), which were conceived,

written, directed, photographed, and edited by the filmmaker fully expressed

his vision to an extent that is unprecedented in American feature film. As

one critic has characterized them, they represent "one of the greatest

sustained individual achievements in the history of American cinema." Yet

the sad fact is that one year after Cassavetes’ death, those eight films

are still almost completely unknown to the average (or even the considerably

above-average) American filmgoer. Ironically enough, if Cassavetes' name is recognized

at all, it is as an actor in other people's movies, rather than as a maker of

his own.*

It is only natural to wonder how

such an extraordinary body of work could have fallen into the cracks so

completely, both commercially and critically. Part of the explanation is simply

the terrifying economics of film distribution and publicity. Lacking the

backing and the budgetary resources of major studio sponsorship, Cassavetes

self-promoted and self-distributed his own work, which means that he actually carried

the film cans from city to city trying to convince a distributor to book his

movie, organizing small-scale screenings at local theaters and giving

interviews to journalists to drum up free publicity. When all was said and

done, the movie might play in ten or twelve cities for a few weeks (if he was

lucky). All things considered, it's probably not that surprising that so few

people saw the films during their extremely limited and brief releases.1

I

would also note in passing that Cassavetes was almost completely ignored by

academic American film criticism

as well. There were virtually no serious essays written on the filmmaker

during

his lifetime. (I don't count the brief and superficial journalistic reviews

the individual movies received during their releases.) That situation began

to

change a little after Cassavetes' death, with a popular American film magazine,

Film Comment, dedicating a special section of one issue to him, and an American

scholarly journal, Post/Script, recently devoting an entire number to a survey

of his life and work. But beyond those two instances, even as I write this,

Cassavetes' films remain a terra incognita for the vast majority of American

film critics. The unavailability of Cassavetes' films on video in America is

traceable to their not being plugged into studio distribution package-deals

(where "ancillary rights" are sold before filming has even begun).

Even at this late date in the video revolution, not one of Cassavetes' eight

fully independent productions is available in the United States on either tape

or disc. (Love Streams was briefly

available on tape several years ago from MGM/UA; it was, however, dropped from

circulation after the most limited of releases.) Gloria, the only Cassavetes

title that is currently available on tape, was one of the three studio productions,

and Big Trouble, which

is generally available on video and is misattributed to Cassavetes, is actually

not his work.

To make a difficult situation

worse, Cassavetes' work fell squarely between the two stools of American film

criticism and viewership – the journalistic and the academic. Consequently,

even when his movies got screened, they often didn't get reviewed (at least

not

sympathetically) or couldn't find an audience. They were entirely too sophisticated

and demanding for the Sneak Previews-type reviewer and audience: the coke and

popcorn crowd, the pop-culture trash collectors, the genre-film slummers. At

the same time, they were entirely too shaggy and baggy to interest the

high-culture devotees who write and read the toniest academic criticism.

Cineastes who look to Europe for Art (or who confuse art with gorgeous

photography and literate dialogue) were the wrong ones to understand

Cassavetes' barbaric yawp.

The commercial coup de grace in

America was probably Cassavetes' refusal to become trendy. There are no fashionable

themes or

movie-of-the-week issues in his entire oeuvre.

His films never punched any of the topical hot buttons within contemporary

film commentary that would have guaranteed them at least a modicum of general

attention.2 Although there are plenty of strong and interesting

women and lots of men who fight for their lives and honor, there is not a single

feminist or

Vietnam vet in all of Cassavetes' work, no more than there are any of the other

staples of "relevant" filmmaking: terrorists, drug deals, venal

policemen, greedy capitalists, or corrupt public officials. Unlike the work

of Spike Lee, David Putnam, or Stanley Kubrick, Cassavetes' films do not lend

themselves to public statements or political stances because the drama is

generated more from contradictions and confusions within a character, than

from

conflicts between characters. This sets his work apart from ninety-nine percent

of other American films. With only the fewest exceptions, American movies

imagine life in terms of a myth with three components to it: 1. Individualism:

The plot revolves around a personal quest led by one main character. He or

she acts largely alone, or with the assistance of a few allies (most commonly,

a

single romantic partner). 2. Competition: The narrative is organized around

conflicts and confrontations between individuals or between an individual and

an institution. 3. Materialism: Practical rewards or penalties are the outcome

of the competition between the opposed characters: fame, money, power, or sex

are the payoffs for the individual's risk-taking behavior.

In short, it is the ideology of

entrepreneurial capitalism, a set of assumptions which virtually every American

feature film internalizes (even those that intend to critique capitalism).

Ostensibly counter-capitalistic films like Silkwood,

Taxi Driver, Wall Street, Working Girl,

and The Godfather are as much in its

thrall as pop culture schlock like Pretty

Woman, Raiders of the Lost Arc, Rocky, and Star Wars. A lone individual fights and triumphs over (or, on rare

occasions, fails to triumph over) personal opponents and worldly obstacles,

with the payoff in the form of tangible rewards–ranging from increased wealth

or social status to winning the girl or getting the job done. It's remarkable

how rarely American films deviate from the formula, and how satisfied viewers

obviously are with it. As anyone who has ever sat through Rambo or Rocky with a

large audience can attest, American filmgoers relish imagining their experience

in terms of personal conflicts and confrontations with practical rewards. The

nature of American society apparently predisposes most viewers to imagine their

lives in these terms–no matter how emotionally and spiritually impoverished

such understandings may be.

Cassavetes' narratives violate

all three tenets of this entrepreneurial ideology. In the first place, his

family-centered films define characters not as loners, but as members of

groups. Not rugged individualism and capitalistic competition, but social

interaction and interpersonal cooperation are the keys to their success. The

qualities most in demand are not Yankee ingenuity, resourcefulness, and

ruthlessness, but sensitiveness, responsiveness, and emotional openness. In the

second place, Cassavetes' narratives are not organized around personal

conflicts between figures. Characters are not pitted against each other in

tests of strength and intelligence. For Cassavetes, our private battles with

ourselves are always more interesting than our public fights with others. The

wars his characters fight are inward. The important struggles in which they are

engaged are attempts to understand themselves and their emotional needs.

Finally, characters' successes or failures are not marked in terms of

capitalistic rewards. What is at issue is not worldly or failure, but emotional

exploration and growth. When the quest of a figure is for self-knowledge and

self-expression, the only gain or loss that ultimately matters is spiritual.

Accordingly, one can actually

reverse the charge that Cassavetes’ work is socially

"disengaged" and politically "irrelevant" or

"naive." While the other sort of film, in effect, buys into

capitalistic understandings of experience in the very organization of its

narrative (even when it may think it is criticizing it), it is

Cassavetes’ work almost alone that offers a profound critique of the

assumptions of entrepreneurial capitalism. The very structures of

Cassavetes’ narratives implicitly criticize the premise the other sort

of

film accepts: the belief that we can be saved and our lives healed by competing

with one another and struggling for worldly success. By these standards,

Silkwood is a far more conservative film than Faces.

The reason Cassavetes’ films

don't appear to engage themselves with public issues is that rather than

focusing on the externals of characters' lives, Cassavetes focuses on how

social ideologies affect their hearts and minds. His films depict the internal,

psychological disruptions of capitalism as being potentially even more

disturbing than its external, economic consequences. Rather than dealing with

the economic or social predations of capitalism, Cassavetes depicts its

emotional consequences: the pernicious effects of bureaucratic organizations

of human relationships, the soul-killing qualities of competitiveness,

the way

business values distort his characters' understandings of the meaning of their

lives. His movies are peopled with small-time entrepreneurs (from Shadows' Ackerman and Too Late Blues’ Frielobe

to Faces' Richard Forst, The Killing of a Chinese Bookie's Cosmo

Vitelli, and Opening Night's Manny

Victor) who get into trouble by trying to organize their emotions and personal

relationships the way they run their businesses.

Asked why he didn't address

public themes the way Oliver Stone or Mike Nichols does, the filmmaker

characteristically replied: "Why should I make movies about things I

already know? I want to make movies about things I don't understand. And anyway

I want to ask people questions about themselves, not about someone else." That

suggests a further explanation for why Cassavetes' films met with incomprehension

during his lifetime. His movies ask questions whose answers are

not nearly as obvious or clear as those in the other sort of film. Furthermore,

they force viewers to question their own everyday lives and actions.

Cassavetes' cinematic agenda is a

deliberately challenging one. While films like the ones I have named are

content to recycle certain basic fictional formulas, Cassavetes attempts to

teach his viewers radically new ways of knowing–new ways of understanding

themselves and others. Cassavetes' films are lessons in new forms of thinking

and feeling–though what it might mean for a film to be a form of thought may

take some explaining. Suffice it to say that the filmmaker fully understood

that confronting the ingrained viewing habits of his viewers might be the

necessary first step in the process of redefining the nature of life and experience

for them.

Cassavetes frequently said that

he was not in the least surprised that most audiences resisted his work. He

knew that reaching viewers in a deeper place might require making them

uncomfortable: “I'm interested in shaking people up, not making them

happy by soothing them. . . . It's never easy. I think that it's only in

'the movies' that it's easy. . . . I don't think people really want

their lives to be easy. It's a United States sickness. In the end it becomes

more difficult. I like things to be difficult so that my life will be

easier.”

Faces illustrates that deliberate

difficulty. Compared with most other films, the behavior of its characters

seems inconsistent and unpredictable. A character who seems witty and sensitive

one moment is boorish and immature the next. A figure who seems aware of his

faults and foibles in one scene is headstrong and self-centered in another.

I remember the first time I saw the film, and how this aspect of it confused

me,

and made me extremely uncomfortable. I was denied the sort of intellectual

and emotional comfort that settling back with one feeling about a character

allowed. I liked them, then I despised them. In one scene I admired their

intelligence or sympathized with their predicament, even as I felt on the basis

of a previous scene that I ought to have contempt for them.

Cassavetes springs his characters

free from the sorts of intentionality that most other films, especially

mainstream American works, accustom us to. The chief way we are able to get a

handle on characters in most other films is by ferreting out a figure's "true intentions." But

in Cassavetes' work, intentions count for almost nothing. They certainly don't

allow us to sort out the good from the

bad, the nice from the nasty.

Virtually all of Cassavetes'

characters (even the most despicable) have good intentions. With only the

fewest exceptions, all of them are sincere. They mean well. Like Mama Longhetti

(who terrorizes her daughter-in-law Mabel in A Woman Under the Influence) or Mister Jensen (the neighbor who

precipitates a family crisis in the same movie), they are trying to do their

best for themselves and their loved ones (even as they may wreck havoc on

everyone around them). Everyone has his reasons (to borrow a phrase from Jean Renoir,

whose characters are similar in this respect)–which is to say that behavior is

generated out of sources far deeper than reasons can describe or motives can

plumb.

However, even to say that

characters have good intentions is not to do justice to their true complexity.

In the majority of scenes and encounters, Cassavetes' characters are liberated

from having any definable intentions at all. Cassavetes' most interesting

characters don't have any fixed, predictable, or static center of being. The films

present behavior and expression that stays psychologically multivalent and

irreducible to motives or goals. The first long scene in Faces can stand

as an illustration. Richard and Freddy are in Jeannie Rapp's home, making an

obvious sexual play for her. But what makes the

moment so strange and gripping is that, in the first place, Cassavetes

suppresses the details of how the three characters came together and who

exactly they are. (Is Jeannie a call girl, an easy pick-up, or a "nice" girl? Are Richard and Freddy married or single, good guys or

con men?) In the second place, and even more importantly, Cassavetes leaves

entirely up in the air why they are where they are, what they want out of the

moment. (Are they looking for a one-night stand, a "meaningful

relationship," just passing time, or what?)

It is impossible to say. We

just

don't know. But the crucial point is that Cassavetes isn't Hitchcock:

clarifying information is not withheld in order to tease the viewer or stoke

up dramatic interest. It is withheld because it doesn't exist, because,

given

Cassavetes' view of life, it can't exist. It is impossible to know what any of

the characters expect from the moment or why they are together, because they

themselves don't know. Richard and Freddy don't know what they "really" want from Jeannie, any more than she knows what she

"really" wants from them. In fact, if they could say, they wouldn't

be nearly as interesting and the scene wouldn't be so fascinating.3 As

Cassavetes once put it: “It's never as clear as it is in movies. People

don't know what they are

doing most of the time. They don't know what they want. It's only in "the

movies" that they know what their problems are and have game plans to deal

with them.

Cassavetes is interested in bringing

forward the vague and the inarticulate in

human awareness. He focuses less on the problems his characters know and

understand than on the hidden confusions in their consciousnesses–confusions

that are hidden even from themselves, since if they knew they were confused,

they wouldn't be as confused as they are. (To the extent that intentions may

be said to exist at all, multiple and contradictory intentions can co-exist

in one

figure, and more than that, the intentions of which a figure is aware may be

opposed to intentions of which he is unaware.) 4

If the effect of this is not

clear, consider Love Streams' Robert

Harmon. He sincerely believes that he opens himself to the women he surrounds

himself with and earnestly tries to understand their deepest feelings (which

he

calls their "secrets"), even as the film itself shows us how he

manipulates them, holds them off at arm's length emotionally, and refuses to

let them into his life.5 But

it would be wrong to call him a hypocrite, since after all, he is not even

aware of his deception. The important lies in his

life are the ones he tells himself. As the filmmaker once said to me:

"Nobody's a phony, the way they are in the movies. People believe in what

they are doing, even when it hurts them and [hurts] others." Robert's

romantic efforts are in earnest; even as, in another sense, they are not in

earnest.

Cassavetes was always more

interested in the ways we fool ourselves than in the ways we fool others. The Killing of a Chinese Bookie presents

confusions of feeling so deep that the individual who is ultimately undone by

them is not even aware of them. Cosmo Vitelli gradually allows the Mob to take

over his life (and his nightclub), but the subtle thing is how imperceptible

the gangsters' triumph over his soul is. As Cosmo struts toward his doom, he

keeps telling himself that he, and not the Mob, is in control. Even as he lets

them take over his life bit by bit, he doesn't realize that he is signing over

to them what even they couldn't have touched without his cooperation: his

definition of himself.

When the film was first released,

a number of reviewers objected to the shagginess of the presentation, the way

it becomes impossible to tell whether or where the precise boundary is crossed

at which Cosmo has lost the emotional battle with the Mob and given himself

away. But that is to miss the point of the film. The blurriness of the line is

its essence. Cassavetes explores the shadow line where the deepest emotional

sell-outs take place–the line where the person selling-out isn't even aware of

it. The film is a study of the lies we tell ourselves about ourselves in order

to hold onto our pride and keep going in life. If the slippery path to hell

were more clearly marked, Cassavetes suggests, we wouldn't have such difficulty

avoiding it. If Cosmo were aware of his emotional weaknesses and moral

emasculation (his need to avoid arguments or confrontations, his boyish desire

to please people and keep everyone around him happy, his escapist impulses as

an artist), he wouldn't be in the trouble he is.

In

comparison with other films' schematic crises and externalized struggles (where

characters face clear-cut problems with well-defined solutions), Cassavetes'

work explores twilight areas in our lives: subtle self-betrayals, secret

bewilderments, and failures of self-awareness. That is, I believe, what he was

getting at when he once said that contemporary filmmakers must move "beyond the artificial conflicts of melodrama," in order to define

"new kinds of problems"–problems more subtle than those generated by

external conflicts. As he said on another occasion, his films attempt to deal

with "characters who have everything they want, but [who] still can't

sleep at night," characters for whom "the problem has become what's

the problem."

In

the service of doing that, it was necessary for him to free his scenes from the

sorts of simplifying dramatic "point" one encounters in conventional

films. When the problem is "what's the problem," the point of a scene

or an encounter between two characters may be its absence of point. When the

real events are not external conflicts, but interior muddlements of feeling,

scenes and characters reveal truths between the actions or the lines of

dialogue, in the beats, the pauses, the hesitations, the moments of

uncertainty.

Husbands was

criticized for the rambling quality of some of its scenes. But Cassavetes

argued that the absence of point in many of the scenes was the point: "The

lack of action was what the picture was about. . . . Sometimes the guys would

just sit there. I mean, [when] somebody dies and it affects you deeply, I don't

know anybody who knows what to do."

To

keep a viewer in the fuzzy places, and to keep the fuzzy places fuzzy and not

falsely to clarify them, it is additionally important for Cassavetes to deny

viewers a privileged point of view on his characters that would simplify or

resolve our understanding of a scene or interaction (just as he denies his

characters privileged insights into themselves or their own motives). There can

be no liberated self-expressions on the part of a character, or absolute

knowledge about a character's intentions on the part of a viewer. Viewers have

no source of knowledge about characters above or beyond the figures' own vexed

self-representations, which never provide direct or easy access to "true" meanings or feelings. There is neither visual nor verbal

presentation of unmediated feeling. Nobody can simply "be"

themselves, or unproblematically "express" something. Every

self-expression is socially mediated, emotionally compromised, inflected by

ulteriority. Arguments, brags, jokes, compliments, criticisms, even expressions

of love all need to be interpreted.

This

is one of the most challenging aspects of Cassavetes' work for a viewer trained

by Hollywood films, which invariably provide fairly direct access to a

character's "true" feelings and beliefs–either by simply having a

character say what he or she means, or by presenting the characters' feelings

in visual terms: through a point-of-view shot, a mood shot, an expressive

lighting effect, an exchange of glances between characters. In Cassavetes'

work, no expression is transparent in the way such stylistic devices presume

(neither to the characters in the film, nor to the audience watching it).

Subjectivity is rejected as the basis for experience. There can be no direct

revelations of consciousness. 6 In a world in which characters can't say what

they are doing, because even they don't know, all the film can depict is raw

behavior.

The

irony was that Cassavetes succeeded so brilliantly at presenting the convoluted

complexities of his characters' performative disarray that most critics wrote

off his work as a mess. He was so successful at freeing his scenes and his

characters' interactions from conventional forms of dramatic shapeliness (which

he called "getting the literary quality out" of the detailed scripts

he wrote as the basis for all of his important work and which survive in

multiple drafts) that critics concluded that his actors were simply making up

their lines and actions in front of the camera as they went along.

While

most Hollywood scripts are written to generate well-turned phrases and cute

repartee as ends in themselves, an examination of Cassavetes' successive drafts

of his scripts demonstrates that his goal was to mess-up overly tidy

expressions, to take scenes and interactions that went too smoothly and rough

them up. The expressive clumsiness in a Cassavetes film is a depiction of

shambling purposes and mixed-up goals. His characters' expressions are confused

because they are confused. (Though, needless to say, that is an entirely

different thing from their creator being confused.) Their lines sound

improvised because their lives are improvised. Cassavetes' characters don't know

what they are doing until they have done it–and even then they frequently

don't know. Gena Rowlands once said that the difference between her husband's

and others' films was that in other movies, characters always look like they

are following some sort of master plan, while in his films they make up their

plans and keep changing their minds about them as they go along.

That

should suggest why there is no greater sign of a character's confusion in these

films than for him to pretend he is not confused, and no greater mess he can

make of things than to attempt to plan out his life. No performers get into

greater trouble than the ones who think they are in control. Our fantasies of

being in control and of knowing what we are doing are the supreme lies we tell

ourselves about ourselves: In Husbands,

Gus's verbal panache–his promiscuous charm–is an attempt to avoid emotional

involvement with the girlfriend he performatively dazzles, even as he

romantically gets in over his head with her anyway. In Shadows, Lelia uses her dazzling powers of self-dramatization to

hold her various boyfriends at a protective distance so that she can't be hurt,

even as she then suffers from the emotional distance she has created. In The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, Cosmo's

pretensions to being calm, cool, and poised in front of the various audiences

he performs for are an attempt to deny, even to himself, the troubles that

beset him and ultimately do him in.

[The

conclusion of the essay:]

The alternative to "shorthand" filmmaking is a longhand scrawl that

is essentially temporal in its effects. To adapt William James' terminology

from Some Problems of Philosophy, Cassavetes offers "concatenated

knowing" in place of "consolidated knowing." Rather than rushing

to a portable meaning (to what Cassavetes dismissively calls "quick,

manufactured truths"), the viewer is forced to live through a changing

course of events. In this view of it, meaning is always in transition: it lives

in endless, energetic substitutions of one interest and focus for another, in

continuous shifts of tone, in fluxional slides of relationship. For Cassavetes,

life is motion, and experience is essentially leaky and slippery. It won't be

pinned down. "Life is in the transitions," in William James' phrase.

Neither life's nor art's meanings can be "caught on to,"

"grabbed," "held," or "kept ahead of."*

Cassavetes'

art is essentially and crucially temporal in the way a piece of music is, not

spatial the way painting, architecture, or sculpture are. As the title of Love Streams suggests,

his work

comprehends the "streaming" of love–the endless movements,

adjustments, swerves of life as it is actually lived. He forces both his

viewers and his characters to throw away their static concepts, to abandon all

fixed positions, in order to plunge into the flow of events.7

To

a viewer accustomed to the other sort of filmmaking, even the most important

scenes and relationships in Cassavetes' work may seem to "get

nowhere," because in Cassavetes' imaginative universe there is really

nowhere to get. There is only a series of shifting positions to be cycled

through. In Emerson's words, "health of body consists in

circulation." 8

Now

though it might be thought that if characters and scenes never get anywhere,

the films must be tedious or boring, the opposite is true. Since a scene or

a relationship doesn't exist to lead to something else, a viewer is never

released from his activity of attention. We can't push the pause button on

our

VCRs (or our minds) anywhere. Go out to get a Coke and come back for the next

scene, and you've missed everything. It's pointless for the person sitting

next to you to fill you in on "how it ended," since the scene doesn't

exist to generate an end-point.9 That

makes Cassavetes' scenes as continuously exciting as listening to a good jazz

performance (even the second or the tenth

time through). In contrast, ordinary films, with their fixed trajectories of

build-up, confrontation, climax, and resolution–more like Burt Bachrach than

Charlie Parker–let us coast most of the time, while we wait for the next

crisis or climax to kick in. The evenhandedness, the refusal to subordinate

the individual impulse to the atemporal architecture, makes these films the

Jackson

Pollocks of cinema.10

Another

way of explaining the process-aspect of Cassavetes' work is to say that

significances are not merely asserted visionarily, abstractly, or impersonally,

but are socially negotiated between individuals in particular acts of practical

performance. If the force of this is not obvious, I would point out that

another reason Cassavetes' work has experienced so much critical

misunderstanding is that most other American film is predicated upon an

entirely different set of expressive premises. The principal meanings in

Hitchcock and Welles, for example, are not generated out of the practical

interactions of characters. They are brought into existence chiefly through

visionary events (in two senses: imaginative visions experienced by the

characters in the film; and visions created by the director for the viewers of

the film).

Pure,

socially unmediated subjectivity (rather than impure, compromised behavior) is

the basis for expression. The eyeline match and the shot/reverse shot define

the relationship of characters as virtually telepathic. The expressive close-up

registers states of personal emotion liberated from the mediated messiness of

speech or action. The point-of-view shot figures the directly available

contents of an individual’s consciousness. Other meanings are generated

by lighting effects, camera movements and framings, editing effects, musical

orchestrations, and the metaphoric inflection of objects in the setting. This

is the form of cinema that American audiences have become adept at

understanding and American critics extremely comfortable at explicating. It is

the dominant line in American film–carried on today by the vast majority of

mainstream filmmakers (by figures as different from one another as Kubrick, De

Palma, Spielberg, Coppola, and Lynch). In this expressive tradition, meanings

are created relatively independent of the particular space and time and

resistance of the actual personal expressions of the individual characters in

a

scene. That is why, in Hitchcock's infamous phrase, actors truly may be treated

as "cattle" in his form of filmmaking. They are the more or less

passive recipients of significances imposed upon them and generated by the

cameraman, the lighting supervisor, the editor, or the director, rather than

being the independent originators of their own personal meanings. In Hitchcock,

a specific camera angle or movement or lighting effect tells us how to feel

about a character or how the character understands his own experience; in

Welles, a tendentious blocking or framing of characters in certain spatial

relationships with each other metaphorically communicates their true

relationship or feelings about each other. Meanings are cut relatively free

from the ebb and flow of social expression and practical personal

performance.11

Such

stylistic occurrences presume that states of knowledge or feeling can be made

directly available to viewers (and that they can, in effect, be weightlessly,

painlessly communicated between characters). In Hitchcock, in particular, to "see" something is to "know" it, and to "know" is

to "be." Nothing could be less like the fragile, vulnerable social

negotiations of meaning and relationship that take place in Cassavetes' scenes,

where expression is never unmediated or unproblematic. The prickly practicalities

of specific times and places and personalities can't be transcended or left

behind. States of personal subjectivity are not liberated from the intricacies

and obliquities of bodily and social expression. Meanings have none of the

expansiveness, impersonality, or metaphoric generality of a visionary

experience. (That is why, to an eye accustomed to visionary stylistics,

Cassavetes' films look confused and disorganized. But it is not the mess of

unplanned, sloppy work that a viewer is witnessing, but the mess of life lived

without visionary releases and metaphoric clarifications.)

There

are no lyrical interludes, visionary stylistics, or point of view shots in

Cassavetes' work. Characters don't "look" meanings (or relationships)

into existence. They don't communicate in shot/reverse "glances."

They don't open their consciousnesses to our view (or to each other). Such

techniques allow the "eye" to separate itself from the "I." They

privilege our visionary capacities over our social expressions of ourselves.

Much of Hitchcock's legacy to film (and to filmmakers like Lynch and

DePalma in particular) is the separation of our socially expressive and our

private visionary impulses, a separation Cassavetes completely refuses to

entertain. For him, imagination must express itself in and through social

interaction–never as an alternative to it.

While

the other kind of film offers us meanings which are pure, static, abstract, and

atemporal, those in Cassavetes' work are continuously subject to loss or decay

in a way that visions, imaginations, or dreams are not. What is brought into

existence in space and time and with the cooperation of other people is always

in imminent danger of being lost in space, time, and social interaction.*

In

Cassavetes' work, not only does the essence of a character not precede his or

her existence, but there might be said to be no essences at all. One's personal

identity is created and maintained in the process of social negotiation with

others. There is no "essential" self apart from its "accidental"

expressions of itself. We make ourselves up as we go along. As something that

must be worked into existence, the self is always in danger of lapsing out of

existence. In William James' phrase, one is "continuously breasting

non-entity," and therefore continuously risking slipping back into

non-entity. Ontological slippage threatens many of Cassavetes' most important

characters: In Minnie and Moskowitz,

when various figures start echoing each others' lines and actions, Cassavetes

is showing us how easy it is to lapse back into being a semiotic function of

one's environment (or one's film). In A

Woman Under the Influence, Opening

Night, and Love Streams, Mabel

Longhetti, Myrtle Gordon, and Sarah Lawson each make themselves so available to

other people's definitions of them that they run the risk of giving themselves

away–losing control of any independent sense of themselves. In The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, Cosmo

Vitelli, in his need to please and entertain the various audiences in front of

which he performs, loses his grip on a self separate from the various costumes

and masks he wears. In the end, he becomes the master of ceremonies as

invisible man: stunningly unable to distinguish his own needs from the needs of

his audience.

It is

precisely because identities and meanings are so fragile and temporally

fugitive in his work that Cassavetes' viewer is compelled to become so active

in his process of keeping up with the shifting figures and significances on the

screen. Cassavetes asks that the viewer work almost as hard as the characters

within the films in order to make and remake meanings that are always in the

process of decay. Cassavetes asks both his viewers and his characters to

embrace a life of present-tense experience. We must stay on the qui vive. Like

the improvisers who function at the center of each of the films, the viewer

must

learn to thrive in a state of perpetual activity, openness, vulnerability, and

exposure–energetically engaged in making something out of each moment without

being able to predict or to predetermine the outcome. The challenges and

dangers of this situation–for both viewers and characters–are obvious. The

reward is a state of empowerment in which meanings are not imposed or received

from outside experience, but are actually made in the course of an active,

passionate relationship with it. We become powerful, temporally engaged,

meaning-makers in a sense very close to the one William James described in “Pragmatism and Humanism”: “In

our cognitive as well as in our

active life we are creative. We add,

both to the subject and to the predicate part of reality. The world stands

readily malleable, waiting to receive its final touches at our hands. Like the

kingdom of heaven, it suffers human violence willingly. Man engenders truths

upon it … For pluralistic pragmatism, truth grows up inside of all the

finite experiences. They lean on each other, but the whole of them, if such a

whole there be, leans on nothing. All ‘homes’ are in finite

experience; finite experience as such is homeless. Nothing outside of the flux

secures the issue of it.”

The process

of breaking free from limiting formulas of response in order to learn how

to make

meanings in a moment by moment activity of improvisation might be said to be

the masterplot of all of Cassavetes’ films. They tell his viewers and his

characters alike that only by plunging unconditionally into the present, to

make something of it here and now, may the possibility of possibility be

brought into existence. This capacity to hold ourselves open and responsive to

the individuals around us, irrespective of our experiences, might in fact be

said to be Cassavetes’ definition of love. In this entirely practical

sense, all of his films are about finding possibilities of emotional

spontaneity and susceptibility in a world which relentlessly mechanizes

behavior and punishes vulnerability. This is the lesson that Minnie must learn

in the course of Minnie and Moskowitz.

As someone who has gone through disastrous relationships with men, she has to

find the courage to open herself to a new relationship in a world without

guarantees. The doom of characters like Zelmo and Morgan is that they

can’t break their patterns. They can’t leave their pasts, their

fears, and memories behind long enough to make a future possible.

In

the dramatic metaphor that informs all of his work, Cassavetes asks his

characters to throw away all of the preformulated scripts of life and become

improvisers of their own identities and relationships. The supreme challenge

with which his work confronts both characters and viewers is whether they and

we are brave enough to throw ourselves headfirst into experiences whose course

we can't ever entirely understand and whose conclusion we can't control. 12

The

result is an extremely challenging state of affairs, and far from an easy one.

It is much easier to abide by the scripts of life, and to stay on the beaten

path. The society of Cassavetes' films is a fiercely predatory and

power-saturated one. It is a world extremely hazardous to the individual's

health, threatening characters with erasure or extinction at every moment.

Cassavetes imagines the most arduous possible universe for his characters to

function within, one that exacts Herculean labors of effort from each

individual, each of whom is continuously tested to the limit of his or her

ability. There is no possibility of poise or relaxation, only a state of

endless struggle and combat.

This

is undoubtedly the source of the common misperception of Cassavetes as a bleak,

pessimistic, or cynical artist. For a certain sort of viewer, his world is

obviously a horrifying, even a nightmarish one. But, as he once put it to me,

Cassavetes "relished the fights." He viewed struggle as the source

of creativity. The challenges are stimulating and invigorating. The difficulty

is

what makes the glory of the performance. It is only in the face of nearly

infinite resistance that we can be heroic. In fighting for our lives we bring

ourselves into the fullest and most exciting states of being. Only in negotiating

danger is virtue born. His characters inhabit the world of the American dream

(in both the positive and the negative senses of the concept)–a realm of both

opportunities and dangers.

Faced

with the inescapability of complication, Cassavetes' glorious improvisers show

us, as Emerson argued in The Conduct of Life, that: "The only path of

escape known in all the worlds of God is performance." (Or as Robert Frost

more wittily put it: "The best way out is always through.") The

improvisational imperative is the only satisfactory response. Emerson, James,

and Cassavetes all agree that mastering the influences–not avoiding them–is

the only adequate course available to us, no matter what.

This

process of plunging into complications, rather than side-stepping them, was

integral to James' definition of American heroism, as he writes near the end

of

his Psychology concerning what he calls the "ethical importance of the

phenomenon of effort." As the final sentence indicates, James was fully

aware that his advice was only for those who were willing to live a

"risky" life "on the perilous edge"–precisely the life

Cassavetes urges on us:

"If

the searching of our hearts and reins be the purpose of this human drama, then

what is sought seems to be what effort we can make. He who can make none is but

a shadow; he who can make much is a hero. The huge world that girdles us about

puts all sorts of questions to us, and tests us in all sorts of ways. . . .

When a dreadful object is presented, or life as a whole turns up its dark

abysses to our view, then the worthless ones among

us lose their hold on the situation altogether, and either escape from its

difficulties by averting their attention, or if they cannot do that,

collapse into yielding masses of plaintiveness and fear. The effort

required for facing and consenting to such objects is beyond their power

to make. But the heroic mind does differently. To it, too, the objects are

sinister and dreadful, unwelcome, incompatible with wished-for things. But

it can face them if necessary, without for that losing its hold on the

rest of life. The world thus finds in the heroic man its worthy match and

mate; and the effort which he is able to put forth to hold himself erect

and keep his heart unshaken is the direct measure of his worth and

function in the game of human life. He can stand this Universe. He can

meet it and keep up his faith in it in the presence of those same features

that lay his weaker brethren low. He can still find a zest in it, not by "ostrich-like

forgetfulness," but

my pure inward willingness to face it with those deterrent objects there. And

hereby he makes himself one of the masters and the lords of life. He must be

counted with henceforth; he

forms a part of human destiny. Neither in the theoretic nor the

practical sphere do we care for, or go for help to, those who have no head

for risks, or sense of living on the perilous edge."

Cassavetes'

three most moving demonstrations of this Jamesian relish of embracing

complications are A Woman Under the

Influence, The Killing of a Chinese

Bookie, and Love Streams–the

first a positive example of the creative stimulations of "braving alien

entanglements" (to quote Robert Frost again), the second a cautionary tale

about the hazards of what James calls "ostrich-like forgetfulness," and

the third a depiction of both possibilities in the contrasted characters of Sarah

Lawson and Robert Harmon. In A

Woman Under the Influence, Mabel Longhetti (who is closely related to Sarah

Lawson) balletically dances her way through circle after circle of familial

entanglements and personal complications. In The Killing of a Chinese Bookie,

Cosmo Vitelli (who resembles Robert Harmon in this respect) demonstrates the

dangers of attempting to avoid

life's complexities. Cosmo is a Sternbergian artist who aspires to use his art

(i.e. his nightclub and the stage shows he writes and choreographs there) as

a

means of escape from the pains and confusions of the world. He fantasizes that

he can run away from worldly problems and take refuge in the beauty and order

of his imaginative creations. 13

Cassavetes'

own career was clearly founded on the opposite of Cosmo's and Robert's belief.

He understood that great art is not an escape from life's messes and

complexities, but a finer embodiment of them, sponsoring a deeper involvement

with them. Our supreme works of art are not hospitals where the wounds incurred

in life's struggles may be nursed and healed, but are the dangerous

battlegrounds themselves, the places where the fiercest wars are fought.

Cassavetes' entire career was devoted to the principle that a film is not an

island of safety and refuge, a Pateresque "world elsewhere," but an

opportunity for emotional exposure, a site of supreme engagement with the

disturbances of experience outside of the movies. (Unfortunately, in the realm

of film criticism, neither the genre-film escapists nor the formalists have yet

assimilated this lesson.)

Cassavetes'

work deserves a place alongside the writing of Emerson and James as a seminal

presentation of a distinctively American imaginative predicament. Cassavetes

transports us to the true America of the imagination: a world in which

relationships and identities are up for redefinition; a world of social,

psychological, and emotional instability; a world of frightening openness and

dangerous vulnerability; a world without rest, relaxation, or pause for the

performer who would meet and master the opportunities it offers.

To

adapt James’s remarks from “The Absolute and the Strenuous

Life,” the world Cassavetes imagines is “always vulnerable, for

some part of it may go astray; and having no eternal edition of it to draw

comfort from, its partisans must always feel to some degree insecure.” In

pushing the envelope of our experience into new places, we are destined always

to be a little off-balance—with the edgy anxiety Cassavetes’

improvisers display. As James argues, in this situation it is necessary for the

individual to have “a certain ultimate hardihood, a certain willingness

to live without assurances or guarantees.” It would be difficult to find

a better description of the strenuous courage of Cassavetes’ greatest and

most inspiring improvisers—Leila, Chet, and Jeannie (in the films of the

fifties and sixties), Moskowitz, Mabel, Gloria, and Sarah (in the films of the

seventies and eighties). Living on “the perilous edge,” they risk

everything—but they also put themselves in a position to discover

something. In James’s words (from “Pragmatism and Religion”),

the result is “a real adventure, with real dangers … [and] with a

social scheme of co-operative work genuinely to be done.”

In

this view of it, our play is serious, but our work can become play. But life is

certainly not a post-modernist romp though a stylistic supermarket. We are far

from the campy parody, the aesthetics of kitsch and deconstructive goofiness,

of David Lynch, John Waters, Robert Townsend, and the Coen and Kuchar brothers.

And we are equally far from the charm, sweetness, politeness, humanism, and

visionary quietism of Woody Allen, Barry Levinson, James Ivory, and John

Sayles. Cassavetes and James imagine life as being harder, more frightening,

more dangerous, and more serious than these filmmakers do.

But,

by the same virtue, Cassavetes and James imagine life's rewards as being keener

as well: they imagine a world in which what James in Some Problems of Philosophy calls "real growth and real

novelty" accrue to those courageous enough not to duck the complexities

and challenges of living, breathing experience–to those who decline to

withdraw from the messes of life as it is actually lived by escaping into

jokes, visions, or dreamy states of good feeling.

It

should be obvious that there is a parable about being an independent filmmaker

implicit in all of this. Cassavetes' life and work demonstrate what Sarah does

in Love Streams: the joys, the

challenges, the hazards, the fun of living on the uncertain, moving edge of

uncontrolled experience. She and her creator show us the consequences of

improvising a trajectory of discovery outside of prefabricated systems of

understanding. They illustrate the excruciating, enlivening results of being

brave enough to plunge into life's expressive complexities, functioning without

guarantees, taking real chances and braving real dangers.

The

critical abuse and commercial neglect of Cassavetes' work during his lifetime

illustrate the lesson Sarah teaches us in Love

Streams: that to live with this abandon is to risk incomprehension and

failure at every turn. To operate at this pitch of intensity, extremity, and

exposure is inevitably to make a fool of oneself in the eyes of the world and

to court dismissal of one's actions as being half-crazy and more than half out

of control. But Cassavetes' inspiring career and the careers of his improvisers

also teach us something else. They teach us the meaning of authentic American

heroism in the brave new world in which we must all learn to live.

______

NOTES:

1Having

taken the eleven films (along with Elaine May's Mikey and Nicky, Cassavetes'

greatest acting performance in a work other than his own) on a national tour

to fifteen cities and a number of

American universities during the year following his death, I can testify that

the ignorance of Cassavetes' work is just as pervasive inside the film studies

programs of our major universities as it is outside of them. (It's an

unfortunate reality that American film students and film professors have almost

as little knowledge of American independent feature filmmaking in general as

does the average man on the street. See my essay "Looking Without

Seeing," in the Winter 1991 issue of Partisan

Review for an extended discussion of this lamentable situation.) back

2 The

coincidence between 1975's A Woman Under

the Influence and the mid-seventies women's movement–which briefly

embraced the film and helped to make it one of Cassavetes' best-known

works–was entirely accidental, as the filmmaker insisted after the movie's

release. He pointed out not only that he had written the script and made the

movie in 1971 and 1972, before feminism had attained a place of prominence

on the national agenda (though it took him until 1975 to get it released),

but

that in any event he completely rejected feminist interpretations of his

central character, making the feminist reading a case of mistaken

identification as far as he was concerned. work does not offer the sort of

obvious cultural generalizations which elicit knee-jerk journalistic discussion

and debate (and which most journalists and journalistic film reviewers naively

equate with "artistic importance"). back

3

Even in Cassavetes' "entertainment" comedy, Minnie and Moskowitz,

the filmmaker's denial of certain kinds of

information about characters' "true" feelings and relationships is

not merely a game of cinematic hide-and-seek. A viewer can't make up his mind

about characters' "real" feelings, because they themselves can't.

If it were otherwise, if the "truth" were simply being concealed

from the viewer, Cassavetes would be merely playing with expectations. We would

be

in the world of David Lynch or the Coen brothers. (I will have more to say

about Minnie and Moskowitz below.)

The process would be fundamentally frivolous and irresponsible. back

4

Though it might seem paradoxical to talk of "intentions" of which a

character is "unaware," it is one of the achievements of Cassavetes'

work to make the meaning of such a concept perfectly clear. Intention is less

a conscious, verbalizable explanation of behavior, than a habitual pattern of

response. back

5

In the scene that takes place between Robert and Susan in front of his house

when she comes to visit him, notice how the kiss he gives her is two opposite

kisses at one and the same time: a warm romantic invitation and a frigid sexual

kiss-off. His interviewing of Joannie in another scene has the same doubleness:

even as his sincerely expressed desire is to try to enter imaginatively into

her wishes, dreams, and fantasy life, his simultaneous intention is to hold

himself aloof and unsympathetic. back

6

In my discussion of Hitchcock and Welles below, I go into a little more deeply

into the ramifications of Cassavetes' avoidance of visionary stylistics. back

7

In the second divorce scene, the judge, the lawyers, Jack, Sarah, and daughter

Debbie jockey for place and position in a quick, glancing emotional dance with

each other as they decide whether Debbie should wait inside the hearing room,

outside in the lobby, on the father's side of the table, or the mother's. In

the Las Vegas scene with the hookers, there are more "shifts" and

"slides" of position (both literally and imaginatively), in one

location (the front seat of a car) and two minutes of screen time than there

are in other entire films. back

8

What would a film criticism look like that understood this sense of meaning in

motion? One can only surmise that it would look quite different from what is

now practiced in so-called "advanced" circles of film commentary

(particularly as conducted by David Bordwell and other formalist critics).

Rather than translating a work into a series of static structures–semiotic

conventions, image patterns, and mythopoetic references–criticism needs to

find a way to talk about the ways meaning boils over any attempt to contain it

within such abstractions, the ways it slips out from under our efforts to fix

it. back

9A

Woman Under the Influence provides

a vivid illustration of the process-quality of Cassavetes’ work. Nick and

Mabel Longhetti merely run a course of events in the time of the narrative. Or

consider the way scenes and interactions are structured in Faces deliberately

to avoid clarifying (that is to say, simplifying) resolutions. Cassavetes' goal

is to prevent characters'

relationships from congealing into abstract positions. The scene between

Richard and Freddy and Jeannie that I already mentioned at the beginning of Faces goes

nowhere in the course of its fifteen minutes of screen time, just at they go

nowhere with each other. In The

Killing of a Chinese Bookie, Cosmo's relationship with his girlfriend Rachel

and her mother Betty stays stimulatingly unresolved throughout the movie. back

10

Another aspect of Cassavetes' narrative "over-all" handling is his

democratic equality of treatment of the various characters–his abandonment of

star-system photographic and narrative hierarchies in his scenes. back

11

It is not too much to argue that Hollywood filmmaking (including the work of

Welles and Hitchcock) is essentially "Romantic" in ways that

Cassavetes declines to be. Rejecting one of the premises of most post-Romantic

art, to return to what might almost be called an Elizabethan (or in cinematic

terms: a Renoirian) aesthetic, Cassavetes tells us that states of consciousness

matter only insofar as they are translatable into forms of practical

interaction. (Hitchcock and Welles tell us the opposite: that the truest part

of us can never be spoken in society, and that our visions and imaginations are

the most important part of us.) Apart from the group, the individual has no

existence. States of subjectivity are of no more expressive importance in life

than dreams are. Not only must the imagination be expressed socially, but that

expressive struggle is the greatest joy and challenge of life. (A Woman Under

the Influence and Love Streams are Cassavetes' clearest

statements of this credo.) back

My Speaking the Language of Desire

(New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989), pp. 81-86, 156-157 and 234-235

goes into much more detail on the difference between a cinema based on the

cultivation of subjectivity and metaphoric transformations of experience and

one devoted to practical, social, temporal expression.

12

For slightly fuller discussions of what I would call "the improvisory

imperative" in Cassavetes' work, see my "Waking up in the Dark,"

The Alaska Quarterly Review, Volume

8, Numbers 3 and 4 (Spring 1990) and "Complex Characters," Film

Comment, May-June, 1989. back

13

This is the lesson that Minnie must learn in the course of Minnie and Moskowitz.

As someone who has gone through a series of disastrous relationships with men,

she has to find the courage to open herself

to a new relationship in a world without guarantees. The doom of characters

like Zelmo and Morgan in the film is that they can't break their patterns. They

can't leave their pasts, their prefabricated routines, their fears and memories

behind long enough to make a future possible. back

Excerpts from

Ray Carney’s award–winning 1990 Kenyon Review John Cassavetes

memorial

essay appear above. This piece was co–winner of the “Best Essay of

the Year by an Younger Author Award.” Only the beginning and the

conclusion of the essay are printed here. To obtain the complete essay,

purchase Ray Carney’s Collected Essays on the Life and Work of John

Cassavetes

Collected Essays on the Life

and Work of John Cassavetes (a packet of essays by Ray Carney previously

published in magazines, newspapers, and periodicals and now unavailable).

Approximately 130 pages. $15.00

A

loose-leaf bound packet of Ray Carney's writings on John Cassavetes is specially

available only through this web site. The packet has

the complete texts of program notes and essays about Cassavetes that were

published by Ray Carney in a variety of film journals and general interest

periodicals between 1989 and the present. It contains more than fifteen

separate pieces—including the keynote essay commissioned by the Sundance

Film Festival for their retrospective of Cassavetes' work at the time of his

death as well as the memorial piece on Cassavetes awarded a prize by The Kenyon Review as "one

of the

best essays of the year by a younger author."

Not

for sale in any store. Available exclusively on this web site for $15.00 under

the same credit payment terms or at the same mailing address as the other

offers.

Other Cassavetes material available directly from Ray Carney:

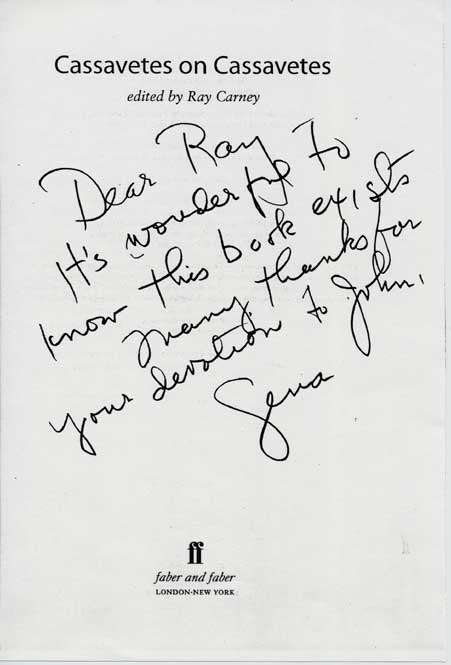

Ray Carney, Cassavetes on

Cassavetes (Faber and Faber in London, and Farrar, Straus and Giroux

in New York), copiously illustrated, paperback, approximately 550 pages.

Available directly from the author for $25.

Cassavetes

on Cassavetes is the autobiography John Cassavetes never lived to

write. It tells an extraordinary saga – thirty years of film history, chronicling

the rise of the American independent movement – as it was lived by

one of its pioneers and one of the most important artists in

the history of the medium. The struggles, the triumphs, the crazy dreams

and frustrations are all here, told in Cassavetes' own words. Cassavetes

on Cassavetes tells the day-by-day story of the making of some of

the greatest and most original works of American film. —from the "Introduction:

John Cassavetes in His Own Words" Cassavetes

on Cassavetes is the autobiography John Cassavetes never lived to

write. It tells an extraordinary saga – thirty years of film history, chronicling

the rise of the American independent movement – as it was lived by

one of its pioneers and one of the most important artists in

the history of the medium. The struggles, the triumphs, the crazy dreams

and frustrations are all here, told in Cassavetes' own words. Cassavetes

on Cassavetes tells the day-by-day story of the making of some of

the greatest and most original works of American film. —from the "Introduction:

John Cassavetes in His Own Words"

Click

here to access a detailed description of the book and a summary of

the topics covered in it.

* * *

Cassavetes on Cassavetes is

available in the United States through Amazon and Barnes

and Noble, and in England through Amazon (UK), Faber

and Faber (UK). It is also available at your local bookseller, or, for

a limited time, directly from the author (in discounted, specially autographed

editions) for $25 via this web site. See

below for information how to order this book directly from this web site

by money order, check, or credit card (using PayPal).

* * *

Ray Carney, The Films of John

Cassavetes: Pragmatism, Modernism, and the Movies

(New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 48 illustrations,

paperback, 322 pages. This book is available directly from the author for $20.

The Films of John Cassavetes tells the inside story of the making

of six of Cassavetes' most important works: Shadows, Faces, Minnie

and Moskowitz, A Woman under the Influence, The Killing

of a Chinese Bookie, and Love Streams.

With the help of almost fifty previously

unpublished photographs from the private collections of Sam Shaw and Larry

Shaw, and excerpts from interviews with the filmmaker and many of his closest

friends, the reader is taken behind the scenes to watch the maverick independent

at work: writing his scripts, rehearsing his actors, blocking their movements,

shooting his scenes, and editing them. Through words and pictures, Cassavetes

is shown to have been a deeply thoughtful and self-aware artist and a profound

commentator.

This iconoclastic, interdisciplinary

study challenges many accepted notions in film history and aesthetics.  Ray

Carney argues that Cassavetes' films participate in a previously unrecognized

form of pragmatic American modernism that, in its ebullient affirmation of

life, not only goes against the world-weariness and despair of many twentieth-century

works of art, but also places his works at odds with the assumptions and

methods of most contemporary film criticism. Ray

Carney argues that Cassavetes' films participate in a previously unrecognized

form of pragmatic American modernism that, in its ebullient affirmation of

life, not only goes against the world-weariness and despair of many twentieth-century

works of art, but also places his works at odds with the assumptions and

methods of most contemporary film criticism.

Cassavetes' films are provocatively

linked to the philosophical writing of Ralph Waldo Emerson, William James,

and John Dewy, both as an illustration of the artistic consequences of a

pragmatic aesthetic and as an example of the challenges and rewards of a

life lived pragmatically. Cassavetes' work is shown to reveal stimulating

new ways of knowing, feeling, and being in the world.

This book is available through Amazon, Barnes

and Noble, your local bookseller, or, for a limited time, directly from

the author (in discounted, specially autographed editions). See

below for information how to order this book directly from the author by money

order, check, or credit card.

Clicking on the above links will

open a new window in your browser. You may return to this page by closing

that window or by clicking on the window for this page again.

* * *

For reviews and critical responses

to The Films of John Cassavetes, please click

here. (Use your back button to return.)

* * *

Ray Carney, John Cassavetes:

The Adventure of Insecurity

(Boston: Company C Publishing, 1999), 25 illustrations, paperback, 68 pages.

This book is available directly from the author for $15.

|

-

New essays

on all of the major films, including Shadows, Faces, Husbands, Minnie

and Moskowitz, A Woman Under the Influence, The Killing

of a Chinese Bookie, Opening Night, and Love Streams

-

New, previously

unknown information about Cassavetes' life and working methods

-

A new,

previously unpublished interview with Ray Carney about Cassavetes

the person

-

Statements

about life and art by Cassavetes

-

Handsomely

illustrated with more than two dozen behind-the-scenes photographs

Click

here to access a detailed description of the book.

|

This

book is available through Amazon, Barnes

and Noble, your local bookseller, or, for a limited time, directly from

the author (in discounted, specially autographed editions). See

below for information how to order this book directly from the author by

money order, check, or credit card. This

book is available through Amazon, Barnes

and Noble, your local bookseller, or, for a limited time, directly from

the author (in discounted, specially autographed editions). See

below for information how to order this book directly from the author by

money order, check, or credit card.

Clicking on the above links will

open a new window in your browser. You may return to this page by closing

that window or by clicking on the window for this page again.

* * *

Ray Carney, Shadows (BFI

Film Classics, ISBN: 0-85170-835-8), 88

pages. This book is available directly from the author via this

web site for $20.

"Ray Carney is a tireless

researcher who probably knows more about the shooting of Shadows than

any other living being, including Cassavetes when he was alive, since Carney,

after all, has the added input of ten or more of the film’s participants

who remember their own unique versions of the reality we all shared."—Maurice

McEndree, producer and editor of Shadows

"Bravo! Cassavetes is fortunate to have such a diligent champion. I am absolutely dumbfounded by the depth of your research into this film.... Your appendix...is a definitive piece of scholarly detective work.... The Robert Aurthur revelation is another bombshell and only leaves me wanting to know more.... The book movingly captures the excitement and dynamic Cassavetes discovered in filmmaking; and the perseverance and struggle of getting it up there on the screen."—Tom Charity, Film Editor, Time Out magazine

John Cassavetes’ Shadows is

generally regarded as the start of the independent feature movement in America.

Made for $40,000 with a nonprofessional cast and crew and borrowed equipment,

the film caused a sensation on its London release in 1960.

The film traces the lives of three

siblings in an African-American family: Hugh, a struggling jazz singer, attempting

to obtain a job and hold onto his dignity; Ben, a Beat drifter who goes from

one fight and girlfriend to another; and Lelia, who has a brief love affair

with a white boy who turns on her when he discovers her race. In a delicate,

semi-comic drama of self-discovery, the main characters are forced to explore

who they are and what really matters in their lives.

Shadows ends with the

title card "The film you have just seen was an improvisation," and

for

decades was hailed as a masterpiece of spontaneity, but shortly before Cassavetes’ death,

he confessed to Ray Carney something

he had never before revealed – that much of the film was scripted. He told him that it was shot twice and that

the scenes in the second version were written by him and Robert Alan Aurthur,

a professional Hollywood screenwriter. For Carney, it was Cassavetes‘ Rosebud.

He spent ten years tracking down the surviving members of the cast and crew,

and piecing together the true story of the making of the film.

Carney takes the reader behind

the scenes to follow every step in the making of the movie – chronicling

the hopes and dreams, the struggles and frustrations, and the ultimate triumph

of the collaboration that resulted in one of the seminal masterworks of American

independent filmmaking.

Highlights of the presentation are

more than 30 illustrations (including the only existing photographs of the

dramatic workshop Cassavetes ran in the late fifties and of the stage on

which much of Shadows was shot, and a still showing a scene from the "lost" first version of the film); and statements by many of the film's actors

and crew members detailing previously unknown events during its creation.

One of the most interesting and original aspects of the book is a nine-page Appendix that "reconstructs" much of the lost first version of the film for the first time. The Appendix

points out more than 100 previously unrecognized differences between the

1957 and 1959 shoots, all of which are identified in detail both by the scene

and the time at which they occur in the current print of the movie (so that

they may be easily located on videotape or DVD by anyone viewing the film).

By comparing the two versions, the

Appendix allows the reader to eavesdrop on Cassavetes' process of revision

and watch his mind at work as he re-thought, re-shot, re-edited his movie.

None of this information, which Carney spent more than five years compiling,

has ever appeared in print before (and, as the presentation reveals, the

few studies that have attempted to deal with this issue prior to this are

proved to have been completely mistaken in their assumptions). The comparison

of the versions and the treatment of Cassavetes' revisionary process is definitive

and final, for all time.

This book is available

through University

of California Press at Berkeley, Amazon, Barnes

and Noble, and in England through Amazon (UK)

and The

British Film Institute. For a limited time, the Shadows book is

also available directly from the author (in discounted, specially autographed

editions) via this web site. See

information below on how to order this book directly from the author by money

order, check, or credit card (PayPal).

Clicking on the above

links will open a new window in your browser. You may return to this page

by closing that window or by clicking on the window for this page again.

For reviews and critical

responses to Ray Carney's book on the making of Shadows, please click

here.

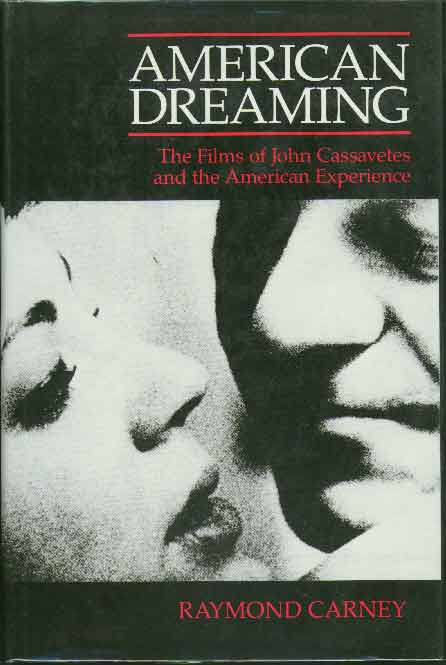

Ray Carney, American

Dreaming: The Films of John Cassavetes and the American Experience (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985). $20.

[From the original

dust jacket description:] John Cassavetes is known to millions of filmgoers

as an actor who has appeared in Rosemary’s Baby, The Dirty

Dozen, Whose Life Is It, Anyway?, Tempest, and many

other Hollywood movies. But what is less known is that Cassavetes acts in

these films chiefly in order to finance his own unique independent productions.

Over the past 25 years, working almost entirely outside the Hollywood establishment,

Cassavetes has written, directed, and produced ten extraordinary films. They

range from romantic comedies like Shadows and Minnie and Moskowitz to

powerful, poignant domestic dramas like Faces and A Woman Under

the Influence to unclassifiable emotional extravaganzas like Husbands, The  Killing

of a Chinese Bookie, and Gloria. Killing

of a Chinese Bookie, and Gloria.

This is the first book-length

study ever devoted to this controversial and iconoclastic filmmaker. It is

the argument of American Dreaming that Cassavetes has single-handedly

produced the most stunningly original and important body of work in contemporary

film. Raymond Carney examines Cassavetes’ life and work in detail,

traces his break with Hollywood, and analyzes the cultural and bureaucratic

forces that drove him to embark on his maverick career. Cassavetes work is

considered in the context of other twentieth-century forms of traditional

and avant-garde expression and is provocatively contrasted with the

better-known work of other American and European filmmakers.

The portrait of John

Cassavetes that emerges in these pages is of an inspiringly idealistic American

dreamer attempting to beat the system and keep alive his dream of personal

freedom and individual expression – just as the characters in the films

excitingly try to keep alive their middle-class dreams of love, freedom,

and self-expression in the hostile emotional and familial environments

in which they function. His films are chronicles of the yearnings, desires,

and frustrations of the American dream. He is America’s truest historian of the inevitable conflict between the ideals and the realities of the American experience.

"By

far the most thorough, ambitious, and far-reaching criticism of Cassavetes'

work has been accomplished by Raymond Carney, currently Professor of

Film and American Studies at Boston University. Carney wrote the first

book-length study of  Cassavetes, who languished in critical obscurity

until the publication of Carney's American Dreaming in 1985....

In Carney's view, to settle the accounts of our lives, to decide once

and for all, is, for Cassavetes, to tumble headlong into the abyss

of nonentity upon which we incessantly verge. Carney argues that Cassavetes

has re-invented the craft of filmmaking in ways that drastically alter

our casual habits of film viewing. To adapt William James' terminology