|

Leigh is not interested

in mocking someone else, but showing us things about ourselves.

As he has often insisted, there is no "them" in his work. Everywhere

we look, we are meant to see ourselves. His hell is never reserved

for other people. That is what makes his films so unsettling. We

are supposed to take them personally. If we don't, we're not really

paying attention.

Keith

and Candice-Marie's dietary and behavioral eccentricities are symptoms

of a state of imaginative derangement that, in Leigh's view, runs throughout

society. They have become cut off from their own experience by culturally-received ideas and emotions. For this relisher of sensory, physical, and

behavioral particularities, there could be no greater heresy than basing

your identity and emotions on abstractions. To do so is to lose touch

with reality and, in effect, make yourself unreal. Characters like Keith

and Candice-Marie have gone insane in a far more insidious and dangerous

way than any of Hitchcock's or John Carpenter's protagonists. Keith

and Candice-Marie's dietary and behavioral eccentricities are symptoms

of a state of imaginative derangement that, in Leigh's view, runs throughout

society. They have become cut off from their own experience by culturally-received ideas and emotions. For this relisher of sensory, physical, and

behavioral particularities, there could be no greater heresy than basing

your identity and emotions on abstractions. To do so is to lose touch

with reality and, in effect, make yourself unreal. Characters like Keith

and Candice-Marie have gone insane in a far more insidious and dangerous

way than any of Hitchcock's or John Carpenter's protagonists.

The ultimate fictions that enthrall Keith

and Candice-Marie are not ideas about the world but about themselves. Their

intellectual relationship to nature is evidence of an even more disturbing

intellectual relationship to their own lives and experiences (a subject which

Leigh will explore further in Abigail's Party and Who's Who). In

their resistance to processed food, Keith and Candice-Marie have unconsciously

swallowed all manner of processed thinking, canned feeling, and shrink-wrapped

selfhood. Their identities are as received, their emotions as dictated by

fashion, and their "views" (in both the perceptual and intellectual senses) as

second-hand as the opinions in the travel-guides they slavishly follow. In

their quest for culturally-certified "naturalness," they have become completely

artificial. Leigh wants us to see that if there is even a shade of

"naturalness" in his movie, it resides in figures like Honkey and Finger, not

Keith and Candice-Marie or the well-trod paths they hike. In this orgy of

intellectual recycling and imaginative role-playing, there is nothing real

left.

All of Leigh's work explores problems of

selfhood and identity, and the major problem with taking your feelings and

opinions from outside of yourself, in Leigh's view, is that you lose track of

who you really are. Keith thinks he is a paragon of reasonableness, when he is

actually an imaginative terrorist. Candice-Marie thinks she is a flower-child

devotee of peace and love, even as she unceasingly nags and bullies Keith about

not being loving enough.

The way we can detect the falseness of

Keith and Candice-Marie's conception of themselves is not only through the

contradiction between what they say and do, and in the ironic discrepancy

between what they say they see and what Leigh shows us (as on the pig farm),

but through the unimaginativeness, inflexibility, and unresponsiveness of their

performances. In Leigh's view, when you play a part that is emotionally and

intellectually inauthentic, the result will always be a mechanical performance.

A false role can never be truly spontaneous, free, or responsive.

In

the implicit dramatic metaphor that informs most of Leigh's work, Keith is a

bad actor or director who mechanically adheres to a pre-established script and

is terrified of any departure from it. That is the significance of his reliance

on texts of various sorts for virtually everything he says and does

(instructions on putting up his tent, notebooks, maps, tour itineraries and

schedules, a numbered guidebook, and the campground regulations he quotes).

Keith is unable to go "off-book," to creatively improvise on the margins of a

text or allow the least bit of creative independence or departure from the

"script." Keith tyrannizes over everyone around him, insisting on adherence to

(and punishing departures from) his pre-determined "scripts" for experience.

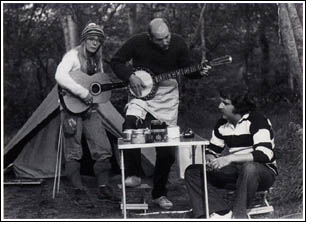

That is the point of a climactic scene late in the film, when Keith and

Candice-Marie invite Ray to their campsite to have tea. Keith functions as a

bad director who attempts to dictate the most minute details of Ray's and

Candice-Marie's blocking (where they should stand for the photograph), line

readings (in the song), and feelings about and interpretation of their roles

(in the talk about nutrition). In

the implicit dramatic metaphor that informs most of Leigh's work, Keith is a

bad actor or director who mechanically adheres to a pre-established script and

is terrified of any departure from it. That is the significance of his reliance

on texts of various sorts for virtually everything he says and does

(instructions on putting up his tent, notebooks, maps, tour itineraries and

schedules, a numbered guidebook, and the campground regulations he quotes).

Keith is unable to go "off-book," to creatively improvise on the margins of a

text or allow the least bit of creative independence or departure from the

"script." Keith tyrannizes over everyone around him, insisting on adherence to

(and punishing departures from) his pre-determined "scripts" for experience.

That is the point of a climactic scene late in the film, when Keith and

Candice-Marie invite Ray to their campsite to have tea. Keith functions as a

bad director who attempts to dictate the most minute details of Ray's and

Candice-Marie's blocking (where they should stand for the photograph), line

readings (in the song), and feelings about and interpretation of their roles

(in the talk about nutrition).

For a filmmaker so clearly committed to

the value of expressive individuality and spontaneity, the result of attempting

to pre-script and over-direct human interaction is not only expressive boredom

but the erasure of fundamental individual differences. While Leigh's cinematic

style is an effort to respect individual structures of feeling and points of

view, Keith's personal style denies the existence of any point of view other

than his own. He cuts everyone and every interaction to fit the Procrustean bed

of his own interests, stage-managing all conversations and directing all

interactions to conform to his own interests. He is a kind of bad artist who

makes life too purposeful, too meaningful, too orderly–and in doing so takes

the spontaneity, surprise, and fun out of experience. He takes the play out of

play....

–Excerpted from Ray Carney, The Films of

Mike Leigh: Embracing the World (London and New York: Cambridge

University Press, 2000).

|

|

Ray

Carney's The Films of Mike Leigh is quite simply the

best book of film criticism I have ever read.

Now I have to say

that I have never read any of Carney's other books (he has

also written books on Cassavetes, Frank Capra, and Carl Dreyer),

which, for all I know, might be even better. But as a friend

of mine put it, 'His writing blows everything else out there

away, even to the point of many times seeming like simply

in a class of his own...different in kind more than degree.'

And although I admit to not having read 'everything else out

there,' I feel the exact same way. Ray Carney's new book has

undeniably rocked my world.

Ray Carney's book

is to what usually passes for film criticism what Mike Leigh's

movies are to what, in Hollywood, usually passes for filmmaking:

a truly radical critique, a whole different animal, and a

solitary voice of sanity that has somehow miraculously managed

to make itself heard over the noise and hullabaloo of this

culture's present-day insanity. |

|

–Caveh

Zahedi, creator of A Little Stiff and I Don't Hate

Las

Vegas Anymore,

in a review in Filmmaker Magazine |

| |

|

| |

Mike Leigh’s work is difficult to pin down. Echoing what Ray Carney says of Leigh’s more blinkered characters, examining these films becomes a lot murkier when you bring too many ideas and film-critical categories to bear. Although not without its strengths and serendipities, Garry Watson’s book suffers from intellectual larding while, like one of Leigh’s more far-sighted characters, Carney and Quart’s gets in amongst the rough-and-tumble....

The Carney and Quart book was the first critical study of Leigh’s work and every subsequent book on Leigh must negotiate its rigor and insight. I have yet to read a book that better approximates my experience of watching Leigh’s films.My one regret is that, apart from the important BBC plays Nuts in May and Abigail’s Party (1977), I have yet to see many of the early works wherein Carney locates the wellspring of Leigh’s improvisatory power and vision.

Animating this study is a distinction between two types

of Leigh characters that resonates culturally, politically and

spiritually across his work. For Carney, there are those like

Rupert and Laetitia Boothe-Braine in High Hopes (1988),

Nicola in Life Is Sweet (1990), and Sebastian in Naked (1993)

who, mired in a mental image of themselves, pigeon-hole

others in prejudices, effectively foreclosing on generous and

responsive solidarity. Then there are those like Cyril and

Shirley in High Hopes, Wendy in Life Is Sweet, and Louise in Naked who have all the foibles, strengths, and self-doubts of

their humanity, and are open to the flows of human interaction.

Alison Steadman’s giggly and affectionate Wendy still

epitomizes the principle of social cohesion in Leigh. It is perhaps

unsurprising that Steadman and Leigh were married,

while the positive response to the density of experience recalls

the thick descriptive methodology through which a Leigh

film is arrived at. Evoking the Dickensian and Lawrentian

views of human sensibility (as Watson points out), Leigh feels

that the individual mindset has consequences for the wider

culture, and by this light the generous impulse in Wendy and

other Leigh characters has been eroded by consumerism and

social mobility in postwar Britain. Not as overtly political as

Ken Loach, Leigh has nevertheless chronicled the domestic

consequences of the decline of the social consensus imagined

by writers from Dickens to George Orwell.

One of the most unexpected aspects of Carney and Quart’s book is the way it puts mainstream American cinema in perspective by comparing it with Leigh’s cinema.With his focus on characters as mannered and tic-ridden “outsides” (as opposed to Hollywood’s granting us access to Forrest Gump’s inner kindness despite the goofy exterior), Leigh charts that elusive quality, the “ordinary” moment—the everyday drama of interaction they never show in Hollywood because it occurs between the heroics.

In doing so, Carney shows, Leigh pulls apart the Enlightenment model of agency and volition on which most American movies depend. Recalling classes he has taught—he is Director of Film Studies at Boston University—Carney describes how Americans are often perplexed by a cinema in which nothing seems to happen. But Leigh’s drama of transformation is rooted in the layered rehearsal of interpersonal dynamics observed with the patience of a European Ozu. Whilst British Leigh commentators have been preoccupied with the writer-director’s purchase on the sociological landscape, Carney convinces us that Leigh and Ozu share a feeling for the interplay of performance and mise-en-scène which moves beyond David Bordwell’s pioneering Ozu dichotomy between modernism and tradition. Leigh’s conception of experience (unlike that of Hollywood) is durational rather than deadlined, heterogeneous rather than hurried. Carney’s examination of space and time in Leigh reveals, as Bordwell has done elsewhere, that the mainstream model of experience conceals as much as it reveals.... |

| |

–Richard Armstrong, a review of Gary Watson, The Cinema of Mike Leigh and Ray Carney and Leonard Quart, The Films of Mike Leigh: Embracing the World, published in Film Quarterly, Dec 2005, Vol. 59, No. 2, pp. 62-63 |

| |

|

| |

No other study sheds such a revealing light on Leigh's background, his influences, his emotional groundings, and, of course, his unique cinematic sensibility....[Carney's The Films of Mike Leigh is a] powerful and multifaceted analysis which welcomes, like Leigh's work, the vibrant eye and the uncalcified consciousness.

|

| |

-- Andrew Hamlin, in a review of Ray Carney's The Films of Mike Leigh: Embracing the World, published in MovieMaker Magazine. |

| To learn

how to obtain this book, click

here |

|