|

It

is difficult to know with any degree of certainty anything that

Trevor and Ronnie are feeling and thinking in The Kiss of Death.

Most of their behavior and expressions do not illustrate definite states

of thought or feeling (and certainly not the states of focused purposefulness

that motivate characters in the other sort of film). Expression becomes

slightly mysterious–as much for the characters in the film as for the

viewers of it. It

is difficult to know with any degree of certainty anything that

Trevor and Ronnie are feeling and thinking in The Kiss of Death.

Most of their behavior and expressions do not illustrate definite states

of thought or feeling (and certainly not the states of focused purposefulness

that motivate characters in the other sort of film). Expression becomes

slightly mysterious–as much for the characters in the film as for the

viewers of it.

Mystery in this sense

is an entirely different thing from the mystifications of Hitchcock

or the Coen brothers. The questions their work raises are ultimately

answerable (and invariably are answered in their films' final

scenes). The questions Leigh's work raises are not puzzles to be

solved but indications of a density of experience that must be lived

into. There is no hidden depth, no unexpressed desire, no secret

identity or relationship to be ferreted out. Leigh is not concealing

Trevor's and Ronnie's thoughts and feelings, but doing something

much more radical: he is liberating their characters from being

organized around (and understood in terms of) fundamental thoughts

and feelings. It is not that intentional depths are veiled (in the

Charles Foster Kane or Norman Bates way), but that they don't exist.

There is no secret intention or thought to be discovered. Trevor

and Ronnie's lives are not organized around central, controlling

motivational states. Even they couldn't tell us what they are doing

most of the time.

Consciousness is dislodged

as a unifying center. Characters played by Meryl Streep and Jack

Nicholson would almost always be able to tell us what they are thinking

or feeling or why they are saying or doing something at any moment.

It is not only that Leigh's characters misunderstand their own motives

and goals (though they repeatedly do); in most scenes they don't

have any particular motives, plans, goals, or ideas behind

what they are doing. They are not trying to be what they

are or to do what they do. Their identities are not only beyond

their abilities to control or change them, they are beyond their

ability to be aware of them. Leigh rejects stylistic or verbal

presentations of underpinning thoughts and feelings, not merely

to make things hard on a viewer, but because he doesn't believe

in the existence of underpinning thoughts and feelings as explanatory

centers.

While stylistic effects

or verbal statements of a character's goals and intentions offer

resolving "deep" views, the forms of acting and performance

Leigh presents leave the viewer studying behavioral surfaces without

access to intentional depths. The viewer cannot escape from the

confusions of expression into the clarities of intention. There

is no release from the turbulent, turbid, mixed messages of the

actual, which is why we can never know figures like Sylvia, Pat,

Mrs. Thornley, Trevor, or Ronnie the way we can know Norman Bates,

Charles Foster Kane, or the Hal 9000 computer.

The emphasis on intentional

states in Hollywood film reflects a unitary conception of personal

identity–as if people were one thing through and through. Apparent

vagaries of behavior and expression are harmonized by being traced

back to a central, unifying thought, emotion, or purpose. Leigh

simply does not believe that our identities are unified in this

way. In his view, a central unity does not necessarily underlie

the heterogeneity of our experiences and expressions. Leigh's most

interesting characters do not have fundamental, overarching "motives"

or "goals." They do not have "plans." They do

not have "visions" of what they "want" or "need."

There is no realm of deep "feelings" or unexpressed "intentions"

to discover. There is no substructure of essential "thoughts,"

"purposes," and "desires" that can clarify the

genuine vagueness, open-endedness, and unformulatedness of their

interactions. Leigh denies that life is organized (and comprehensible)

in terms of essential states of consciousness.

The very point of Leigh's

narratives is to create situations where game plans do not apply.

They suspend the characters in an unresolved middle ground of feelings

and relationships that maximize the possibilities of unpredictable,

unbalanced, unprogrammatic interaction. Characters don't have purposes

and goals; as in life, they discover what they are doing only after

they have done it–if they discover it at all. They just can't see

very far–which can be sad in a serious moment or endear them to

us in a comic moment.

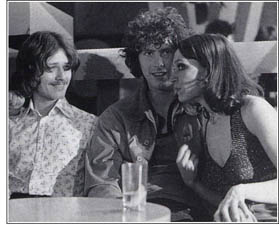

The

Kiss of Death is organized around the interactions of fairly confused

and unreflective young people who do little more than "hang out"

together. Trevor and Ronnie, as friends, and Trevor and Linda and Ronnie

and Sandra, as potential lovers, feel their way toward or away from each

other in an awkward, hesitant emotional dance in which there are frequent

missteps, lots of stepping on toes, and no way of seeing beyond the present

position. Given who they are and what they are doing, they really can't

know what they want from each other (or whether they want anything at

all). If Trevor and Ronnie knew what they were doing, what they wanted,

where they were heading, or how to get there–if they had clear purposes

and definite goals–they wouldn't be nearly as interesting as they are.

They would become the kind of characters played by Charlie Sheen or John

Travolta. The Kiss of Death would become Saturday Night Fever. The

Kiss of Death is organized around the interactions of fairly confused

and unreflective young people who do little more than "hang out"

together. Trevor and Ronnie, as friends, and Trevor and Linda and Ronnie

and Sandra, as potential lovers, feel their way toward or away from each

other in an awkward, hesitant emotional dance in which there are frequent

missteps, lots of stepping on toes, and no way of seeing beyond the present

position. Given who they are and what they are doing, they really can't

know what they want from each other (or whether they want anything at

all). If Trevor and Ronnie knew what they were doing, what they wanted,

where they were heading, or how to get there–if they had clear purposes

and definite goals–they wouldn't be nearly as interesting as they are.

They would become the kind of characters played by Charlie Sheen or John

Travolta. The Kiss of Death would become Saturday Night Fever.

In the sequence that

culminates in Trevor and Linda's "kiss of death" scene,

for example, it is impossible to know exactly what Trevor wants

out of the encounter or what his intentions are not because his

feelings and intentions are concealed from a viewer, but because

they are concealed from him. To put it more accurately, Trevor doesn't

have definite feelings and intentions. He doesn't know what

he wants from the encounter.

In fact, there are few

surer signs of limitation in Leigh's work than for characters to

think they do know who they are, what they want, where they

are headed, or what they are doing. To assign a destination to desire

is to stunt life and limit possibility. If you think you know what

you are doing, you are almost always wrong. Pat and Peter have clear

goals and purposes; Norman, Sylvia, and Hilda don't. Mr. Thornley

knows what he wants; Naseem and Ann feel their way step by step.

Keith lives by a game plan; Ray, Honkey, and Finger don't even know

what they are doing while they are doing it. Barbara is on a mission;

Colin isn't. It is evidence of Linda and Sandra's limitations in

The Kiss of Death that they do have clear-cut purposes

and goals (attempting to use sex to manipulate and control Trevor

and Ronnie). All of The Kiss of Death is devoted to frustrating

their designs for living....

–Excerpted from Ray

Carney, The Films of Mike Leigh: Embracing the World (London

and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

|

|

Ray

Carney's The Films of Mike Leigh is quite simply the

best book of film criticism I have ever read.

Now I have to say

that I have never read any of Carney's other books (he has

also written books on Cassavetes, Frank Capra, and Carl Dreyer),

which, for all I know, might be even better. But as a friend

of mine put it, 'His writing blows everything else out there

away, even to the point of many times seeming like simply

in a class of his own...different in kind more than degree.'

And although I admit to not having read 'everything else out

there,' I feel the exact same way. Ray Carney's new book has

undeniably rocked my world.

Ray Carney's book

is to what usually passes for film criticism what Mike Leigh's

movies are to what, in Hollywood, usually passes for filmmaking:

a truly radical critique, a whole different animal, and a

solitary voice of sanity that has somehow miraculously managed

to make itself heard over the noise and hullabaloo of this

culture's present-day insanity. |

|

–Caveh

Zahedi, creator of A Little Stiff and I Don't Hate

Las

Vegas Anymore,

in a review in Filmmaker Magazine |

| |

|

| |

Mike Leigh’s work is difficult to pin down. Echoing what Ray Carney says of Leigh’s more blinkered characters, examining these films becomes a lot murkier when you bring too many ideas and film-critical categories to bear. Although not without its strengths and serendipities, Garry Watson’s book suffers from intellectual larding while, like one of Leigh’s more far-sighted characters, Carney and Quart’s gets in amongst the rough-and-tumble....

The Carney and Quart book was the first critical study of Leigh’s work and every subsequent book on Leigh must negotiate its rigor and insight. I have yet to read a book that better approximates my experience of watching Leigh’s films.My one regret is that, apart from the important BBC plays Nuts in May and Abigail’s Party (1977), I have yet to see many of the early works wherein Carney locates the wellspring of Leigh’s improvisatory power and vision.

Animating this study is a distinction between two types

of Leigh characters that resonates culturally, politically and

spiritually across his work. For Carney, there are those like

Rupert and Laetitia Boothe-Braine in High Hopes (1988),

Nicola in Life Is Sweet (1990), and Sebastian in Naked (1993)

who, mired in a mental image of themselves, pigeon-hole

others in prejudices, effectively foreclosing on generous and

responsive solidarity. Then there are those like Cyril and

Shirley in High Hopes, Wendy in Life Is Sweet, and Louise in Naked who have all the foibles, strengths, and self-doubts of

their humanity, and are open to the flows of human interaction.

Alison Steadman’s giggly and affectionate Wendy still

epitomizes the principle of social cohesion in Leigh. It is perhaps

unsurprising that Steadman and Leigh were married,

while the positive response to the density of experience recalls

the thick descriptive methodology through which a Leigh

film is arrived at. Evoking the Dickensian and Lawrentian

views of human sensibility (as Watson points out), Leigh feels

that the individual mindset has consequences for the wider

culture, and by this light the generous impulse in Wendy and

other Leigh characters has been eroded by consumerism and

social mobility in postwar Britain. Not as overtly political as

Ken Loach, Leigh has nevertheless chronicled the domestic

consequences of the decline of the social consensus imagined

by writers from Dickens to George Orwell.

One of the most unexpected aspects of Carney and Quart’s book is the way it puts mainstream American cinema in perspective by comparing it with Leigh’s cinema.With his focus on characters as mannered and tic-ridden “outsides” (as opposed to Hollywood’s granting us access to Forrest Gump’s inner kindness despite the goofy exterior), Leigh charts that elusive quality, the “ordinary” moment—the everyday drama of interaction they never show in Hollywood because it occurs between the heroics.

In doing so, Carney shows, Leigh pulls apart the Enlightenment model of agency and volition on which most American movies depend. Recalling classes he has taught—he is Director of Film Studies at Boston University—Carney describes how Americans are often perplexed by a cinema in which nothing seems to happen. But Leigh’s drama of transformation is rooted in the layered rehearsal of interpersonal dynamics observed with the patience of a European Ozu. Whilst British Leigh commentators have been preoccupied with the writer-director’s purchase on the sociological landscape, Carney convinces us that Leigh and Ozu share a feeling for the interplay of performance and mise-en-scène which moves beyond David Bordwell’s pioneering Ozu dichotomy between modernism and tradition. Leigh’s conception of experience (unlike that of Hollywood) is durational rather than deadlined, heterogeneous rather than hurried. Carney’s examination of space and time in Leigh reveals, as Bordwell has done elsewhere, that the mainstream model of experience conceals as much as it reveals.... |

| |

–Richard Armstrong, a review of Gary Watson, The Cinema of Mike Leigh and Ray Carney and Leonard Quart, The Films of Mike Leigh: Embracing the World, published in Film Quarterly, Dec 2005, Vol. 59, No. 2, pp. 62-63 |

| |

|

| |

No other study sheds such a revealing light on Leigh's background, his influences, his emotional groundings, and, of course, his unique cinematic sensibility....[Carney's The Films of Mike Leigh is a] powerful and multifaceted analysis which welcomes, like Leigh's work, the vibrant eye and the uncalcified consciousness.

|

| |

-- Andrew Hamlin, in a review of Ray Carney's The Films of Mike Leigh: Embracing the World, published in MovieMaker Magazine. |

| To learn

how to obtain this book, click

here |

|