|

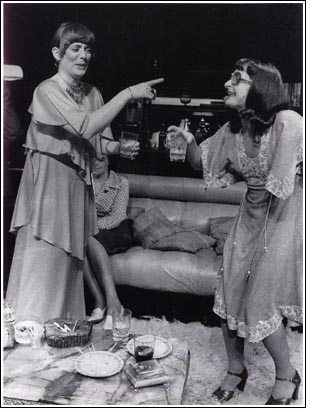

Abigail's

Party is a

house of mirrors in which reflected images have completely replaced

the originals–Beverly, for example, being less a hostess than something

much more unsettling: someone playing at being a hostess.

In a sense, there is no Beverly. When we look for her we find only

an actress playing a part, a ventriloquist's dummy mouthing someone

else's words, an impersonation of a person. She has given up her

identity, such as it is, to play a role, which she acts out

not only in public but, more disturbingly, even in private. That

is the importance of the opening minute or so in which she is alone

on camera. We watch her "acting" even when no one else

is present. She is not performing for an audience–her husband or

her guests, but doing something much spookier: For herself. She

is validating herself to herself. Abigail's

Party is a

house of mirrors in which reflected images have completely replaced

the originals–Beverly, for example, being less a hostess than something

much more unsettling: someone playing at being a hostess.

In a sense, there is no Beverly. When we look for her we find only

an actress playing a part, a ventriloquist's dummy mouthing someone

else's words, an impersonation of a person. She has given up her

identity, such as it is, to play a role, which she acts out

not only in public but, more disturbingly, even in private. That

is the importance of the opening minute or so in which she is alone

on camera. We watch her "acting" even when no one else

is present. She is not performing for an audience–her husband or

her guests, but doing something much spookier: For herself. She

is validating herself to herself.

In this night of the

living dead, there is no Beverly separable from the part she plays.

Her identity is completely synthetic–a shaky structure of

prefab "attitudes," poses, self-regarding routines, and

shop-worn hostess-with-the-mostest affectations. Like some brilliant,

performing circus animal, Beverly provides a dazzling "display"

of canned phrases, gestures, and tones that simulate states of thinking,

feeling, and caring without ever getting within three martinis of

the reality.

We can recognize the

theatricality of Beverly's performance not only through Alison Steadman's tonal archness in her line delivery, which inserts brackets

around each of Beverly's gestures and quotation marks around each

of her utterances, but even in the script. There is something artificial,

imitated, derivative, or inauthentic about virtually every line

of dialogue Beverly utters. It all feels "scripted"–and

it is, not by Leigh, of course, but by Beverly.

Beverly inhabits a realm–call

it hostess-speak–in which verbal expressions bear no relationship

to real feelings (or an inverse relationship, as in the case of

the syrupy "please" she intermittently coos in Laurence's

direction, which is not in the least a polite request but a snarled

imperative and threat). Like the Hollywood air kissing Beverly's

speech resembles, social interaction in this world becomes a kind

of bad acting in which you "indicate" your emotions instead

of actually feeling them. (Real, messy emotion would only get in

the way, impeding the smoothness of the performance and embarrassing

the audience.) Since each of the participants in the drama knows

it is all theater, the fraudulence, the archness, is not concealed

but cultivated and proclaimed, as a way of expanding their identities

and intensifying their presence.

As that way of putting

it is meant to suggest, the problem Leigh is examining is much deeper

than what is normally connoted by insincerity. Beverly (like all

of the other characters in Abigail's Party) is not covering

up her real feelings and thoughts. That would be an entirely more

conventional dramatic situation. It would suggest that she knows

what she is doing. It would imply that she was simply trying to

fool people (a fairly simple situation in life and art), when the

real problem is that she is fooling herself (a much more interesting

state of affairs). Beverly is completely and utterly sincere; she

means what she says; she is not being deceitful. Which is the true

problem. There is no reality lurking in the depths; everything

is fake. Beverly's ideas and emotions are no different from

her jewelry: both are equally cheap knock-offs. Her most private,

inner experiences are as performance not only through Alison Steadman's tonal archness in her line delivery,èd as her expressions.

Most films, particularly

American ones, cultivate what might be called a "surface-depth"

understanding of the relation of falsity and truth. Surfaces, appearances,

expressions are potentially delusive or misleading; truth lies in

the depths. It is hidden somewhere underneath visible expressions.

If you cross-examined Laurence and Beverly in private, and dug for

the truth, you could get them to confess to their lies. This simply

is not the situation Leigh imagines. He holds us on the surface

and, in fact, tells us that the surfaces are all there are. There

is no realm of "truth" underneath or distinguishable from

the realm of "falsehood." There are no secrets to exhume.

There are no psychological depths to mine–or at least none that

matter–in Abigail's Party . No one is being deceitful. No

one is covering up anything. That would simplify understanding.

We could dive down and discover the truth as we do in films like

Citizen Kane or Casablanca. The situation Leigh imagines–here

and in all of his work–is far more complex. There is no escape

from slippery, shifting, multivalent surfaces. There is no realm

of unsullied, uninflected reality underneath. Everything is mixed.

We must live in the flux....

–Excerpted from Ray

Carney, The Films of Mike Leigh: Embracing the World (London

and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

|

|

|

Ray

Carney's The Films of Mike Leigh is quite simply the

best book of film criticism I have ever read.

Now I have to say

that I have never read any of Carney's other books (he has

also written books on Cassavetes, Frank Capra, and Carl Dreyer),

which, for all I know, might be even better. But as a friend

of mine put it, 'His writing blows everything else out there

away, even to the point of many times seeming like simply

in a class of his own...different in kind more than degree.'

And although I admit to not having read 'everything else out

there,' I feel the exact same way. Ray Carney's new book has

undeniably rocked my world.

Ray Carney's book

is to what usually passes for film criticism what Mike Leigh's

movies are to what, in Hollywood, usually passes for filmmaking:

a truly radical critique, a whole different animal, and a

solitary voice of sanity that has somehow miraculously managed

to make itself heard over the noise and hullabaloo of this

culture's present-day insanity.

|

|

–Caveh

Zahedi, creator of A Little Stiff and I Don't Hate

Las

Vegas Anymore,

in a review in Filmmaker Magazine

|

| To learn

how to obtain this book, click

here |

|