|

This page

only contains excerpts from Ray Carney's writing about Frank Capra. To

read more, consult his book American Vision by clicking

here.

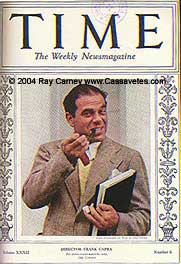

A Memorial Piece

The Two Capras – and My Capra

Click

here for best printing of text

Frank Capra's death in 1991

marked the end of an era. The last major director who began in the golden

age of the silents was gone. Capra lived the entire history of Hollywood,

in his thirty-six features directing many of its greatest stars—including

Clark Gable, Barbara Stanwyck, Jimmy Stewart, Gary Cooper, Spencer Tracy,

Katharine Hepburn, Bette Davis, and Peter Falk—and producing some

of its most memorable movies, from It Happened One Night, Mr.

Deeds Goes to Town, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, to Meet

John Doe, It's a Wonderful Life, and Pocketful of Miracles.

At the peak of his career, in the decade and a half from the early 1930s

to the late 1940s, he was without question America's best known and most

beloved filmmaker.

In the months and years since

his death, numerous eulogistic tributes and references to his work have

appeared on radio and television and in newspapers and magazines. They

have displayed a remarkable degree of consensus about his films. Yet I

must say that, to my mind, almost every single one of them has completely

missed the point of his life and work. Their Capra is a cinematic Norman

Rockwell—sentimental and nougatty, defending family values, celebrating

small-town life, and championing (as the commentators never tire of repeating)

"the common man"—whoever in the world that might be. In the months and years since

his death, numerous eulogistic tributes and references to his work have

appeared on radio and television and in newspapers and magazines. They

have displayed a remarkable degree of consensus about his films. Yet I

must say that, to my mind, almost every single one of them has completely

missed the point of his life and work. Their Capra is a cinematic Norman

Rockwell—sentimental and nougatty, defending family values, celebrating

small-town life, and championing (as the commentators never tire of repeating)

"the common man"—whoever in the world that might be.

Their Capra was someone out

of a mythical American golden age, a man who never existed in a past that

never was, someone quaint and antiquated and infinitely distant from the

present moment, like Santa Claus someone adults love but know that only

children or Walt Disney really believe in. Still worse, some of the appreciations

of Capra's work sketched a man only Jerry Falwell or a Fellow of the Hoover

Institute could endorse—a Capra of the Pledge of Allegiance, a man

who looked out across America and congratulated himself that, at least

in These United States, God was in his heaven and all was right with the

world. (If you don't like it, you can leave.) Their version of "The

Frank Capra Story" clearly would cast a B-movie actor named Ronald

Reagan in the title role.

I wondered if we had seen the

same films. Their Capra is emphatically not the Capra I knew and loved.

Their Capra is not the Capra I spent five years writing a book about.

The Capra whose work meant—and still means—so much to me was

a completely different man from theirs. Rather than being the populist

champion of the guy on the street, the Capra I knew from Mr. Deeds

Goes to Town, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, and Meet John

Doe showed how sheep-like the masses are and how dangerous democracy

itself is—how mobs can be manipulated into believing practically

anything a demagogue or a newspaper wants them to. While the Capra of

the eulogists hearkened back to a Father Knows Best America of

smugness, safety, and complacency, the Capra I knew dramatized social

disruption and personal insecurity. Almost all of his films began by uprooting

the main characters, yanking them out of small towns and family support

systems, and plunking them down in big cities and institutions where they

had to fight to hold on to their sense of who they were and what they

believed. The worlds in which the lead figures made their way were not

cozy and warm, but power—saturated, predatory, and life-threatening.

When Longfellow Deeds dares to act or think independently, without clearing

his words with a team of corporate lawyers before he says or does something,

the American legal system is mobilized against him and he is put on trial

to defend his own sanity. When Jefferson Smith attempts to beat the American

political system without first playing the old "go along and get

along" game, the bureaucratic machinery of the entire United States

Senate shifts into gear to silence him. An all too familiar negative ad

campaign whips up an instant public movement to impeach him. As a newspaper

publisher named Jim Taylor brags, and as Mr. Smith Goes to Washington

itself resoundingly affirms: public opinion easily can be "Taylor-made"

to suit any political purpose. Sound familiar? That's our America, not

some Golden Age Camelot.

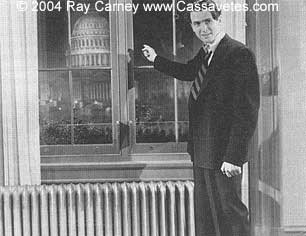

For a reality check, I'd remind

a contemporary viewer that the subversiveness of Capra's work was not

lost on the real-world subjects of his movies. Following an advance screening

of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington in Washington D.C., legislation

was introduced in the Senate whose ultimate goal was to block the release

of the film and to persuade Columbia to destroy the negative. For a reality check, I'd remind

a contemporary viewer that the subversiveness of Capra's work was not

lost on the real-world subjects of his movies. Following an advance screening

of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington in Washington D.C., legislation

was introduced in the Senate whose ultimate goal was to block the release

of the film and to persuade Columbia to destroy the negative.

Rather than celebrating the

power of the common man in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Capra

treats rugged individualism as a myth only fools or children still believe

in, a fairy tale concocted to give the masses the illusion of democracy.

The film tells us that political leaders are not born but made—"Taylor-made"—created

by saturation ad campaigns, PR blitzes, journalistic shabbiness, and political

expediency. Politicians are processed, packaged, advertised, and sold

to the public no differently from any other piece of merchandise. Sound

familiar? That's our present-day culture of celebrity. The newspapers

are no different now than they were then.

The ironically titled Meet

John Doe goes even further than Mr. Smith Goes to Washington

did. It turns the American dream that anybody can become president into

a nightmare vision of a national, fascistic political movement organized

around an inspirational leader who doesn't even exist: "John Doe"

is a fiction created by a public relations campaign and played by a hired

performer. Capra demonstrates how imperiled our identities are, how easily

we can lose ourselves in systems that make us over in their image, even

as, like the character who plays "Doe," we may not even realize

that we are giving ourselves away.

The commentators treat Capra's

films as if they were paeans to the common man's power to speak common

sense, but those aren't the movies I saw. In the eulogists' descriptions

of them, Robert Conway, Longfellow Deeds, Jefferson Smith, and George

Bailey are pacified. Their imaginative extremity is tamed. Their films

are robbed of their melodramatic intensity and power. Look at the movies

again if you have forgotten. These characters are desperate, wild-eyed

American dreamers. Their films are full of charged glances, stuttering

silences, and operatic urgencies of expression. My Capra is a poet of

suffering and tragedy, whose protagonists fall back on lurid, melodramatic

gasps and silences, like nothing we encounter in a Rockwell painting or

a Disney movie.

Capra's 1946 masterwork, It's

a Wonderful Life, is often cited as conclusive evidence of his Saturday

Evening Post vision of life, when in fact the reason it can still

bring tears to a viewer's eyes is the toughness of the vision of experience.

Rather than treating life as one long Thanksgiving dinner of togetherness

and contentment, Capra focuses on the cracks in the facade of the happy-face

American way of life that Norman Rockwell, Gary Bauer, and the publications

of the Heritage Foundation conveniently paper over. Rather than cheerleading

for "traditional values," Capra exposes the repressions of small-town

American capitalism, and the spiritual emptiness of the Protestant work

ethic. He shows us the emotional and imaginative bankruptcy of Chamber

of Commerce systems of value and the hollowness of the American culture

of acquisitiveness.

Forced by economic necessity

and family responsibility to keep the people who depend upon him happy,

George Bailey's life in Bedford Falls is one frustration after another.

He has to sell-out the dreams of his youth and the ideals of his adulthood

in order to maintain a positive cash flow. He has to mortgage his desires

to pay for his responsibilities. It's not an endorsement but a critique

of our Infomercial culture. Forced by economic necessity

and family responsibility to keep the people who depend upon him happy,

George Bailey's life in Bedford Falls is one frustration after another.

He has to sell-out the dreams of his youth and the ideals of his adulthood

in order to maintain a positive cash flow. He has to mortgage his desires

to pay for his responsibilities. It's not an endorsement but a critique

of our Infomercial culture.

In contrast to the Bill Buckley/Malcolm

Forbes/George Bush fairy tale of capitalism triumphant, Capra shows us

how difficult, dangerous, frightening, and exciting the real American

experience is. He dramatizes the difficulty of translating dreams and

desires into practical, lived realities, and how much—sometimes it

seems not less than everything—is always lost in the translation.

Buckley and Forbes are Norman Rockwells by comparison.

Capra suspends George Bailey

between irreconcilable alternatives. He captures the contradictions of

the social system around him by organizing George's drama around a series

of mutually exclusive alternatives which almost tear George apart (and

eventually force him to the point of suicide)—with family values,

small town responsibilities, and the renunciation of personal pleasure

on one side; and the gratification of the life of the imagination and

the senses on the other. Far from being a safe-haven for development (in

both the personal and real-estate senses), Bedford Falls is as predatory,

prying, and power-saturated as the big cities in the earlier films. In

a series of contrasts—between the eroticism of Violet Bix and the

domesticity of Mary Hatch, between the dangerous excitement of Pottersville

and the safe boredom of Bedford Falls, between the free expression of

the individual's imaginative impulses and their sublimation into family

and social responsibilities—Capra captures the contradictions of

our own lives. His film honors both our passions and our commitments;

both our lust for Violet and our need for Mary; both our wild-eyed quest

to escape the confines of our social responsibilities, and the fears and

loneliness that lie on the other side of social embeddedness. That was

the Capra I wrote about in my book. But is it any wonder that every other

serious American film critic has ignored this more complex Capra? It's

much easier to treat him as a huckster of the American dream?

And then there are the endings.

It's almost as if what Capra actually presented on screen is so disturbing

that we need to soften it in remembering it. Like the audiences who saw

the films the first time round, we need the obligatory happy endings that

Capra tacked on as their final scenes to help us to forget the disturbing

experiences that preceded them.

The Capra I want to remember

captures the contradictions, complexities, strains, struggles, and emotional

and imaginative displacements of our own present-day culture. He is not

a sentimental relic of a simpler time and place-Bauer, Buckley, and Forbes,

and Bush are that-but a profound historian of the present. In that sense,

he is still with us, still helping us to understand our lives.

This page

only contains excerpts from Ray Carney's writing about Frank Capra. To

read more, consult his book American Vision by clicking

here.

|