|

This world is one of such pervasive

systems of control and interpretation that there is simply no way for

John to break free into an assertion of mere individuality in the final

movement of the film, no matter what he intends or does. Personal intention

counts for little or nothing in this world (perhaps as little as it counts

for in a modern bureaucracy). The machine inscribes individuals within

its own alternative "intentional" structure, independent of

their will or wishes. It gives their acts meanings and values beyond their

personal knowledge or control. How radically and profoundly at odds this

is with the traditional Hollywood film, grounded in its sentimental post-Romantic

exaltation of the autonomous ego, needs no comment.

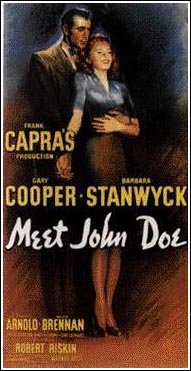

Capra's

most powerful image of the pervasiveness of the systems of control

and

understanding around John is contained in the scene in which John attempts

to tell the truth, to speak personally and as a mere individual to

the

John Doe Convention (though the utter impossibility and meaninglessness

of merely personal and individual speech in this situation–in

a convention, on a stage, in front of a crowd of thousands of people–is

the point of the scene). Having just had Norton's effort to use the

John Doe movement

for his own political purposes revealed to him (and the passivity of

his role in the discovery is relevant–he does not seek out

the truth but simply has it disclosed to him by Connell), he leaves

Norton's mansion

and rushes to the field where thousands of his followers have assembled.

His intention is to talk to them man-to-man, to tell them the truth candidly

and personally, but Capra's narrative, photography, and editing tell

us

how radically displaced the individual presence or personal voice is

in this institutional universe. One cannot talk to a convention man-to-man;

one cannot talk to thousands of people personally and intimately. Capra's

layered visual field reminds us one final time of all of the layers of

technological and bureaucratic packaging that contain and control discourse

in this world, from the radio announcers looking down on the stage from

their sound booths above the crowd to the public-address system that

strips

the intimacy from the tones of one's voice. (The irony of this taking

place in the first baseball field we have seen John actually present

in

the film needs no underlining; but a baseball player, especially, should

realize that self-expression on the diamond is possible only in terms

of obedience to impersonal rules and regulations.) Capra's layered sound

track and contrapuntal editing demonstrate that the technologies of knowledge

and understanding are as completely in place in the field as they were

during his speech in the radio studio earlier. The technology that allows

Doe's voice potentially to reach thousands of individuals by the same

virtue necessarily robs him of a personal presence. Every technology

is

precisely as repressive as it is expressive. Capra's

most powerful image of the pervasiveness of the systems of control

and

understanding around John is contained in the scene in which John attempts

to tell the truth, to speak personally and as a mere individual to

the

John Doe Convention (though the utter impossibility and meaninglessness

of merely personal and individual speech in this situation–in

a convention, on a stage, in front of a crowd of thousands of people–is

the point of the scene). Having just had Norton's effort to use the

John Doe movement

for his own political purposes revealed to him (and the passivity of

his role in the discovery is relevant–he does not seek out

the truth but simply has it disclosed to him by Connell), he leaves

Norton's mansion

and rushes to the field where thousands of his followers have assembled.

His intention is to talk to them man-to-man, to tell them the truth candidly

and personally, but Capra's narrative, photography, and editing tell

us

how radically displaced the individual presence or personal voice is

in this institutional universe. One cannot talk to a convention man-to-man;

one cannot talk to thousands of people personally and intimately. Capra's

layered visual field reminds us one final time of all of the layers of

technological and bureaucratic packaging that contain and control discourse

in this world, from the radio announcers looking down on the stage from

their sound booths above the crowd to the public-address system that

strips

the intimacy from the tones of one's voice. (The irony of this taking

place in the first baseball field we have seen John actually present

in

the film needs no underlining; but a baseball player, especially, should

realize that self-expression on the diamond is possible only in terms

of obedience to impersonal rules and regulations.) Capra's layered sound

track and contrapuntal editing demonstrate that the technologies of knowledge

and understanding are as completely in place in the field as they were

during his speech in the radio studio earlier. The technology that allows

Doe's voice potentially to reach thousands of individuals by the same

virtue necessarily robs him of a personal presence. Every technology

is

precisely as repressive as it is expressive.

Doe makes his way through the

crowd in the stadium to the stage, only minutes ahead of Norton's men,

who are determined to stop him. Many of the shots of the convention are

deliberately not direct shots of John or of the crowd but are shots

of others–for example, radio announcers–looking at and describing John

or the crowd to us and to their listeners. That is one of the things it

means to say that experience is always repressively mediated in this world.

The alternation of close-up shots with shots from the radio booth and

the use of a layered sound track remind us that these contents are always

contained. Both the visual and the acoustic effects are presented as layer

after layer of packaging and merchandising. We are reminded of how the

human figure and voice exist here only insofar as they are transmittable

by a technology of information processing. In this study of visual and

acoustic "perspectives" (in both the cinematic and the Nietzschean

sense), events acquire significance only insofar as they are put in perspective''

by these technologies.

John is only a step ahead of

Norton's henchmen, and every second counts, but even once he has pushed

his way through the crowd and arrived on stage he cannot speak. He has

to wait for the ovation greeting him to die down. Then a patriotic anthem

has to be sung. Then a minister rises to offer the benediction and a silent

prayer for "all of the John Does in the world."

Crowds of people, a national

anthem, a prayer: The film metaphorically equates the hordes of ordinary

citizens, the state, and the church as cooperating, interlocking forms

of repression. All three are surrogates for and extensions of the moral,

intellectual, and social repressiveness that Norton and his storm troopers

represent. They keep John from speaking just as effectively as Norton

does. Just as he is finally about to speak, Norton and his men arrive

and move into action. They are at least as adept at the technologies of

control as are society, the church, and the state. Newspapers denouncing

him as an impostor have been printed up in advance, just in case of this

eventuality. Cries are sent up by stooges in the audience to shout John

down, and the instant he begins to speak and to accuse Norton from the

stage, in the final coup de grace, the wires to the amplifiers are cut.

This last event is one of the

most powerful in all of Capra's work. Capra's close–up on the wire cutting

makes it almost as tangible and painful as if we were watching

John's vocal cords being cut before our eyes. Deeds and Smith were at

least in control of their own voices. Whether or not anyone listened,

they could at least hoarsely, hesitantly, passionately talk–to remind

us that individual speakers were at least hypothetically still at the

center of institutions, to restore an eccentric personal voice and tone

to a system of discourse otherwise mechanically normalized and denuded

of personality. That is what has changed in this film. This is a world

in which even the individual human voice becomes inaudible except insofar

as it can find a way to patch itself into the licensed networks

of knowledge, to plug itself into the power system. With that almost surgically

painful severing of John's vocal cords, the film might just as well have

ended. The self is too small and weak to escape the systems (both cinematic

and institutional) that create and regulate expression in this film.

In effect, the self as a free

and autonomous agent does not exist. The technology has done it in,

erased or replaced it, as it will again, perhaps even more finally

and definitively, in Capra's last important film, State of the Union.

That is why every possible ending to Doe represents a form

of suicide for John. Whether he literally kills himself by jumping from

the top of a building or only symbolically erases himself by becoming

part of Norton's network of faceless, personality-less puppets, or by

becoming the symbolic head of the John Doe movement, the individual, eccentric,

quirky, personal self has been written out of life and the film. Even

suicide is superfluous or redundant insofar as "John Doe" has

never lived, and "Long John" Willoughby has already committed

suicide by an act of self–erasure long before.

The argument has been made

that in Doe Capra is parodying the mythopoetic structures of his

earlier work, playing with the filmic, as well as the social technologies

of creating instant heroes. To talk about play or parody presumes a degree

of detachment, control, and ironic bemusement that the film and Capra's

account of the worried, anxious making of it nowhere communicates. Rather

than being characterized by playful detachment, Doe is Capra's

most disturbed work and the one most torn by conflicts of feeling. It

is his most troubled and out-of-control work, and there is no reason to

doubt his own account of his confusion about and dissatisfaction with

the final film and with each of the five endings he made for it. It is

possible, however, to feel that this confusion was a creative one. Capra

brings all of the basic assumptions of the immediately preceding films

into question. His form inadvertently overwhelms his characters' powers.

The master of the depiction of individual imaginative energy and creative

social performance, for the first time in his career, recognizes and is

able to depict a system of social, institutional, and psychological controls

that is fully as powerful as his individual performers and able to frustrate,

absorb, or rechannel into its own repressive systems of relationship all

of their free energies. Doe is a crisis film in which everything

Capra had previously taken for granted is worried and puzzled, even the

technologies of his own filmmaking, since, as I have already argued, the

most pervasive of the systems "John Doe" is inscribed within,

even more than the John Doe Club network and the political and journalistic

systems, is the cinematic matrix of knowledge and interpretation that

Capra's layered sound tracks, deep-focus photography, contextual editing,

and complex narrative create around him. Out of that crisis of confidence

in his own organizations of experience, as well as that new acknowledgment

of the potential power and pervasiveness of the world's systems and arrangements,

comes Capra's greatest film, It's a Wonderful Life....

This page only

contains excerpts and selected passages from Ray Carney's American

Vision: The Films of Frank Capra. To obtain the book from which this

discussion is excerpted, click

here.

|