|

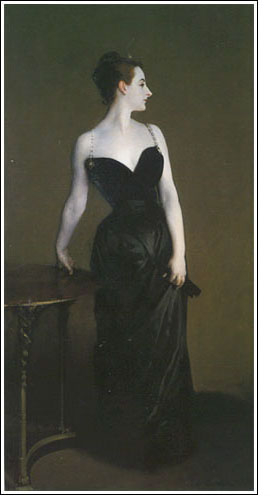

In Sargent, posing becomes

a means of self-composition. Madame X, his portrait of Madame Gautreau,

tells us with every aspect of her theatricality–the turn of her head,

the studied placement of her right hand on the "prop" of the

table next to her, the slight angling of her upper body, the daring décolletage

of her stunning "costume"–that she is creating a deliberately

calculated effect. One thinks of the famous colloquy between Isabel Archer

and Madame Merle, in chapter 19 of The Portrait of a Lady, about

the importance (or unimportance) of costume and props to the expression

of the self:

"When you've lived as

long as I you'll see that every human being has his shell and that you

must take the shell into account. By the shell I mean the whole envelope

of circumstances. There's no such thing as an isolated man or woman;

we're each made up of some cluster of appurtenances. What shall we call

our 'self? Where does it begin? Where does it end? It overflows into

everything that belongs to us–and then it flows back again. I know

a large part of myself is in the clothes I choose to wear. I've a great

respect for things! One's self–for other people–is one's expression

of one's self; and one's house, one's furniture, one's garments, the

books one reads, the company one keeps–these things are all expressive."

This was very metaphysical;

not more so, however than several observations Madame Merle had already

made. Isabel was fond of metaphysics, but was unable to accompany her

friend into this bold analysis of human personality. "I don't agree

with you. I think it is just the other way. I don't know whether I succeed

in expressing myself, but I know that nothing else expresses me. Nothing

that belongs to me is any measure of me; everything's on the contrary

a limit, a barrier, and a perfectly arbitrary one. Certainly the clothes

which, as you say, I choose to wear, don't express me; and heaven forbid

they should!"

"You dress very well,"

Madame Merle lightly interposed.

"Possibly; but I don't

care to be judged by that. My clothes may express the dressmaker, but

they don't express me. To begin with it's not my own choice that I wear

them; they're imposed upon me by society."

"Should you prefer to

go without them?" Madame Merle enquired in a tone which virtually

terminated the discussion.

There

is no question but that Madame Gautreau would side with Madame Merle in

this dispute, and probably be just as dismissive of Isabel's commitment

to the existence of a naked self outside of social definitions and beyond

forms of expression. To complete the artistic parallel, if Madame Merle

is a figure out of Sargent, Isabel is a figure out of Eakins, a

figure who reminds us how separate she is from any costume she happens

to wear at the moment and how costumes do not, cannot contain or express

her. Yet Sargent's Madame Gautreau and James's Madame Merle, in an alternative

way, also express a notion of the transcendental self. Insofar as they

stage their effects and self-expressions and are not merely identical

with them or unselfconsciously defined by them, we are aware of a self

beyond the costume, behind the gesture, underneath the role, a self not

completely represented by the part it plays. This is a crucial (and commonly

misunderstood) point, and it helps one to see why theatrical impulses

and transcendental aspirations are not opposed concepts (and why Madame

Merle and Isabel Archer are therefore not entirely opposed characters,

as one might naively conclude). They are rather alternative responses

on the part of the self to the same condition of having too much imagination

for expression in ordinary, received social roles and functions. While

Isabel Archer quests after a disencumbered state of freedom, Madame Merle

(like Eugenia of The Europeans and many of James's other heroines)

transforms herself into a flamboyant actress of her own life. It is in

this sense that Sargent and Eakins, though apparently so entirely opposed

in their art, actually reflect a common cultural background and a shared

set of assumptions about self-expression. As we shall see in the early

films, Barbara Stanwyck will be an actress who will stimulate Capra to

entertain both conceptions of the self. In some scenes and films she will

play a visionary questing for a release from worldly categories and definitions

similar to Isabel Archer. In others she will play a consummate actress

of her own life in a dazzling display of a mastery of alternative tones,

styles, and costumes. The two kinds of characters are really only the

same character imagined in two different forms of self-expression. There

is no question but that Madame Gautreau would side with Madame Merle in

this dispute, and probably be just as dismissive of Isabel's commitment

to the existence of a naked self outside of social definitions and beyond

forms of expression. To complete the artistic parallel, if Madame Merle

is a figure out of Sargent, Isabel is a figure out of Eakins, a

figure who reminds us how separate she is from any costume she happens

to wear at the moment and how costumes do not, cannot contain or express

her. Yet Sargent's Madame Gautreau and James's Madame Merle, in an alternative

way, also express a notion of the transcendental self. Insofar as they

stage their effects and self-expressions and are not merely identical

with them or unselfconsciously defined by them, we are aware of a self

beyond the costume, behind the gesture, underneath the role, a self not

completely represented by the part it plays. This is a crucial (and commonly

misunderstood) point, and it helps one to see why theatrical impulses

and transcendental aspirations are not opposed concepts (and why Madame

Merle and Isabel Archer are therefore not entirely opposed characters,

as one might naively conclude). They are rather alternative responses

on the part of the self to the same condition of having too much imagination

for expression in ordinary, received social roles and functions. While

Isabel Archer quests after a disencumbered state of freedom, Madame Merle

(like Eugenia of The Europeans and many of James's other heroines)

transforms herself into a flamboyant actress of her own life. It is in

this sense that Sargent and Eakins, though apparently so entirely opposed

in their art, actually reflect a common cultural background and a shared

set of assumptions about self-expression. As we shall see in the early

films, Barbara Stanwyck will be an actress who will stimulate Capra to

entertain both conceptions of the self. In some scenes and films she will

play a visionary questing for a release from worldly categories and definitions

similar to Isabel Archer. In others she will play a consummate actress

of her own life in a dazzling display of a mastery of alternative tones,

styles, and costumes. The two kinds of characters are really only the

same character imagined in two different forms of self-expression.

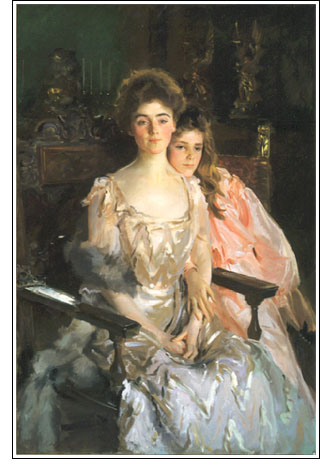

If we did not already know

this, one of Sargent's great double portraits would have helped us to

see it. I have in mind Mrs. Fiske Warren and Her Daughter Rachel. In

the figures of the portrait Sargent embodies the two alternatives for

the self I am describing. The daughter is Isabel Archer–all vague, undeveloped,

uncostumed dreaming; the mother is Madame Merle–poised, proper, posed,

social presence of mind. We can read the two tightly intertwined and enjambed

figures (and the two heads in particular) in several different ways: as

the private self and the public manner; as figures of the past and the

future; of innocent possibility and experienced realization; but however

we gloss them, it is clear that in the unfocused, indirect gaze into the

distance of the daughter Sargent is giving us a view of a state of reverie

or imagination that necessarily will be, he suggests, sooner or later

expressed socially in the fixed, direct look into our eyes of the mother.

The figures are really one figure viewed twice, he tells us.

Of

course, the painting also raises the implicit question of whether there

is more of a loss or of a gain in this process of the mother's socialization

of the daughter's incoherent reverie or vision but then, James's novels

and Capra's films repeatedly ask the same question. In all three artists'

work, a character's alluring theatricality (in the case of the first Sargent

painting) or social polish and poise (in the case of the second) represent

the working off of unplaceable imaginative energies in stylistic flair.

Yet, at the same time, they are also evidence of the anxiety, fragility,

and vulnerability of the achieved self. Sargent's sitters are never relaxed

or at ease. There is a tension, a willfulness to their creations of themselves

which Sargent brings out in his figures that entirely distinguishes his

portraits from those one finds in the English country-house portrait tradition

(with which his work is often unfortunately lumped). In that tradition,

stable identities can be taken for granted, can be reclined into amid

the silks, the setters, and the grand, green pastoral settings. That lack

of ease in James's, Sargent's, and Capra's work results in the sense of

anxiety and vulnerability that one feels in their most ambitious figures,

even as it is also the source of their creativity and the stimulus

to the dangerously daring performances these figures launch themselves

on, which are absent from the English tradition. Of

course, the painting also raises the implicit question of whether there

is more of a loss or of a gain in this process of the mother's socialization

of the daughter's incoherent reverie or vision but then, James's novels

and Capra's films repeatedly ask the same question. In all three artists'

work, a character's alluring theatricality (in the case of the first Sargent

painting) or social polish and poise (in the case of the second) represent

the working off of unplaceable imaginative energies in stylistic flair.

Yet, at the same time, they are also evidence of the anxiety, fragility,

and vulnerability of the achieved self. Sargent's sitters are never relaxed

or at ease. There is a tension, a willfulness to their creations of themselves

which Sargent brings out in his figures that entirely distinguishes his

portraits from those one finds in the English country-house portrait tradition

(with which his work is often unfortunately lumped). In that tradition,

stable identities can be taken for granted, can be reclined into amid

the silks, the setters, and the grand, green pastoral settings. That lack

of ease in James's, Sargent's, and Capra's work results in the sense of

anxiety and vulnerability that one feels in their most ambitious figures,

even as it is also the source of their creativity and the stimulus

to the dangerously daring performances these figures launch themselves

on, which are absent from the English tradition.

In a similar vein, Capra's

films explore the dangers and difficulties as well as the stimulations

and incentives available to these precariously poised American selves.

They ask the questions that are central to understanding our culture.

How is the bootstrap project of creating a self and a place for the self

in the world to be accomplished? Do social forms of performance express

our imaginative possibilities or frustrate them? What is the destiny of

the weak and vulnerable self that breaks free from institutional supports

and imagines itself an exception to all preordained social forms? Can

it ever find expression for its imagination in the real world of space

and time, within the repressive structures of social organization and

language, or is it doomed to perpetual imaginative homelessness? James,

Sargent, Homer, Hopper, and Capra are all asking related questions....

The preceding

material is a brief excerpt from Ray Carney's writing about American painting.

To obtain the complete text of this piece or to read more discussions

of American art, thought, and culture by Prof. Carney, please consult

any of the three following books: American Vision (Cambridge University

Press); Morris Dickstein, ed. The Revival of Pragmatism: New Essays

on Social Thought, Law, and Culture (Duke University Press); and Townsend

Ludington, ed. A Modern Mosaic: Art and Modernism in the United States

(University of North Carolina Press). Information about how to obtain

these books is available by clicking

here.

|