|

Michael Fried's new study takes

as its starting point a recognition of the inadequacy of two of the principal

ways art critics have approached nineteenth-century American painting

in the past: on the one hand, in terms of genres, and, on the other, under

the rubric of "realism." As Fried is aware, American art has

been inadvertently patronized (first by foreign critics, subsequently

by our own native commentators) by these approaches insofar as they are

what he calls strategies of "normalization." They are ways of

neutralizing the potential imaginative eccentricities or disturbances

of individual works.

The problem with genre study

as it is normally carried on is two-fold: In the first place, it almost

always implicitly cordons off a work in the never-never land of merely

artistic connections and statements and thus marginalizes it. In the second

place, and more importantly, in establishing a series of archetypal antecedents

and contexts for a particular piece, genre studies inevitably minimize

the imaginative intensity and individuality of the individual artist's

expression in the work (by incorporating the piece into a larger, pre-established

tradition of expression in which it is said to participate). In this sense,

genre study is a strategy of containment and control, a way of exorcising

potentially disturbing spirits.

For example, to take one of

the most ubiquitous categories in American criticism, to call a painting

(or a novel or a film, for that matter) a "romance," and then

to proceed to associate it with a particular tradition of "American

romantic" expression is, first, automatically to remove it to a certain

distance from life and expression as they exist outside of the work of

art; and, second, implicitly to discount any expressive eccentricities

or intensities that occur within it. The expressive wildnesses in Hawthorne,

Cole, and Capra can all be controlled with this strategy. Anything especially

eccentric, intense, or threatening about a particular work can be explained

away as being a function of the form. The expressive audacity or extremity

one encounters in it can be shifted away from the personal predicament

of the artist and attributed to the expressive demands of the genre.

Although they may seem to be

alternatives to genre ghetto-izing, conventionally "realistic"

narrative, biographical, or ideological accounts of a work's meaning are

equally repressive of the energies it may attempt to release. Fried argues

that the assumptions that define American realism as a critical doctrine

are, in effect, only variations on the genre patronization of a work.

"Reality" as critics describe it in American paintings, novels,

and films is, after all, only one more set of normalizing, stabilizing,

or distancing conventions by means of which–rather than allowing a work

to assault or wound us–we contain its expressive threat. The doctrine

of "American realism" (like that of "American romanticism")

is a way of hiding from ourselves the strangeness or intensity of the

work of our greatest artists. That is because–like genre categorization–realism

as a critical doctrine involves assimilating a work to pre-existing normative

notions of expression (which are sufficiently stable and dependable for

everyone to agree to call them "reality").

Fried is not attacking straw

men. The dominant line of nineteenth-century American art criticism as

practiced in our own century has been more or less entirely conducted

within this neutralizing conception of expression. One can read through

the major book-length treatments of Sargent's, Homer's, or Eakins' work

published in the twentieth century–from the pioneering work of Gordon

Hendricks and Lloyd Goodrich to that of John Wilmerding and Elizabeth

Johns more recently–and find almost no exceptions to this normative notion

of artistic expression. What is left out of these realist accounts–just

as it is left out of genre accounts–is, again, the imaginative conflicts

and the personal eccentricities and idiosyncrasies that went into the

work.

In the particular instance

of the work of Thomas Eakins, the painter Fried is in the present case

most interested in, Johns' concept of "American heroism" or

Wilmerding's or Hendricks' descriptions of the psychological origins and

social meanings of Eakins' work more or less reduce the paintings to being

expressions of historical conditions or biographical events in the artist's

life. Insofar as they appeal to stable, acceptable, normative notions

of reality independent of the works in question, they assume that, in

effect, we all know what the painter and the painting are about before

we even look at the work. The painting is an expression of the life and

times of the artist. It dissolves into the biographical and historical

conditions that are alleged to have generated it. There are no energies

that escape such a form of understanding, or dare to question it. Anything

that would radically threaten or violate normative assumptions about the

established order of things is left out of the account.

If, under these other approaches,

anything that is a little strange or wild in a work is ignored or explained

away, Fried's goal might be said to be to restore the craziness or eccentricity

to the works he examines. In his own words, his attempt is to counter

"the blandly normalizing bias" of realism and genre study with

a heightened appreciation of what he calls, at different points, the "obsessions,"

the "calculated aggressions," the "monstrosity," or

the "disturbance" of the works he examines. There are many ways

this might be done. The particular tack Fried takes is to attempt to shift

our attention back from the genre to the imagination of the individual

artist, or to put it another way, to restore to the critical description

of the object a sense of the pressure of the idiosyncratic individual

imagination engaged in a vexed and ambivalent act of creation.

As I have already suggested,

there could be no more heroic and valuable task for a critic to perform,

especially within the realm of nineteenth-century American art criticism.

Such a revaluation of American artistic expression is overdue, and Fried

is not alone in his attempt to save the artists he loves from the cozy

and complacent misreadings of over-familiarity: among the younger generation

of critics, Bryan Jay Wolf, David Lubin, and Albert Boime are following

in Fried's footsteps in comparable efforts to save American art from the

blandified readings of previous American art criticism.

But the proof of the pudding

is in the eating, not in the noble intentions of the cook, and one moves

through Fried's essay with a rising appreciation of the failure of his

effort. The problem arises not with his general critical goal, which borders

on being heroic, but with his particular means of achieving it. As the

language I quoted above would suggest, Fried finds what he calls a thematics

of violence, aggression, and distortion in Eakins' work. But the principal

violence documented in his book, unfortunately, is the violence his own

language and procedures do to the works he examines.

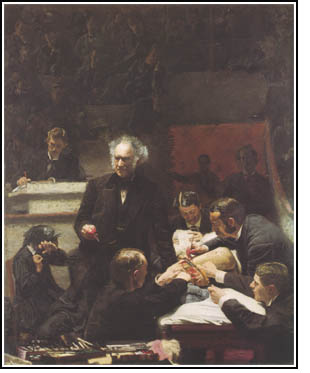

Consider the following discussion of the figure who has come to be accepted

as that of the mother of the patient on the operating table in Eakins'

The Gross Clinic. She sits off to one side of the central space

in obvious grief and pain, as her son is operated on. Here is Fried's

account of her:

The extremity of affect

expressed in her left hand's violent contortion is apprehended by

the viewer as a threat–at a minimum, an offense–to vision as such,

though simultaneously the viewer's attention is drawn, as if against

its will, to the thin gold wedding band on the fourth finger of that

hand. This is a further instance of the ambivalence or dividedness

I have already attributed to the viewer's relation to The Gross

Clinic. (The offense to vision is compounded by what almost seems

a hint of monstrosity in the region of the mother's forehead . . .

. I don't mean to suggest that the mother's features are imagined

by Eakins as literally monstrous, only that it is impossible for the

viewer to make sense of what is depicted of her profile and that this

is nearly as disturbing as the clawlike hand itself.)

This

passage can stand as a summary of many of the essential qualities of Fried's

writing. On the positive side, one wants to acknowledge how lively his

prose is. His criticism is linguistically thrilling in a way that one

would imagine would at least initially keep even the most bovine students

spell-bound at its energy and ingenuity (though it must be admitted that

the frissons and melodramatics ultimately becomes cloying and incoherent

to a reader taking it in larger than lecture-room doses in a book like

this). This

passage can stand as a summary of many of the essential qualities of Fried's

writing. On the positive side, one wants to acknowledge how lively his

prose is. His criticism is linguistically thrilling in a way that one

would imagine would at least initially keep even the most bovine students

spell-bound at its energy and ingenuity (though it must be admitted that

the frissons and melodramatics ultimately becomes cloying and incoherent

to a reader taking it in larger than lecture-room doses in a book like

this).

But the thrills and chills

of Fried's writing are also the problem with it. Every page, practically

every paragraph, is as overwrought in its diction as this one. This is

more than a stylistic quibble. Fried is committed in advance to a thematics

of violence and disfiguration in the works he discusses (and in his larger

argumentative project is committed to maintaining that painting and writing

in general enact a scene of violent and aggressive disfigurement that

repels and confounds vision) and his language throughout the book merely

plays out the consequences of the general conclusions at which he has

obviously already arrived by the time he approaches the specific works

in question. The result is a case study in argumentative tendentiousness

and the loading of terms.

In this linguistic hot-house,

everything is extraordinary and bizarre. Nothing is in the mid-range of

human experience. If a figure is turned or bent, it is "monstrous."

If a fist is tensed, it is "clawlike." If an aspect of a painting

is complexly visually presented, it is "a threat to vision,"

or it is what Fried, in a discussion of Will Schuster and Blackman

Going Shooting for Rail, calls "explosive" of vision:

The distancing called for

by "pictorial" seeing is further encouraged by the most

remarkable feature of Will Schuster, the incandescent red of

Schuster's long-sleeved shirt, which by virtue of its coloristic explosiveness

repels the viewer from the painting as with the force of a blast.

Insofar as it also explodes the unity that "pictorial" seeing

characteristically seeks to confirm, it recalls the peculiar, anarchic

intensity of the reds not only in The Gross Clinic but in the

early domestic interior scenes as well.

We have seen a comparable melodramatization

of the process of artistic understanding in literary criticism most notoriously

in what has come to be called reader-response analysis–though I

think that Fried's viewer-response theatrics even more usefully can be

traced

back before Stanley Fish to the art appreciative onanism of Pater, Fry,

or Bell. What all of these critics have in common is their tendency to

make the text the site for a series of self-dramatizing imaginative associations

and flights of fancy. It may make for a kind of high drama, but such

criticism

ultimately directs our attention more to the performance of the critic

than to that of the artist he explicates.

As Fried's pun involving explosiveness

in the shooting painting suggests, it is the critic who is doing all of

the associating and connecting in these passages, not Eakins or his works.

That is why such adjectival pressure has to be exerted by Fried. That

is why his argument becomes so rhetorical. Precisely because the work

is not authorizing his imaginative investment in it, he must make whatever

interest that will accrue. Fried does it all. The figure of the distraught

woman in The Gross Clinic is disfigured and made illegible only

by Fried's treatment of it–not by Eakins'. In Will Schuster the

gun is pointedly not firing, and the moment commemorated is emphatically

not one that refers to its explosiveness, only Fried's pun does. (The

painting is, in fact, about the patience, precision, and balance involved

in stalking game and aiming at it–about a state of concentration and

meditative poise–almost the opposite of the connotations evoked by Fried's

overly ingenious reading.)

While Fried ponders the "extremity

of affect" he encounters in Eakins, what he doesn't realize is that

the reader is more probably pondering the "extremity of affect"

he encounters in Fried's own descriptions. Why is this critic so overwrought?

Why is he so committed to a rhetoric of violence, distortion, and anarchy

even where it is obviously inappropriate–not only in Will Schuster,

but also in the domestic interior scenes which he alludes to at the end

of the previous quotation which are tonally closer to being meditative

than to being "anarchic" in any respect? (Even if his essay

was originally commissioned to appear in Representations, there

must be more to account for Fried's rhetoric than the current fashionableness

of such violences of language and reference in "advanced" intellectual

journals.)

I hope I don't seem merely

an ad hominem hit man. Fried's personal psychohistory is entirely

less important than the larger critical issues his work raises. In the

second half of his book Fried switches his commentary from the work of

Thomas Eakins to that of Stephen Crane. His approach to literature is,

if anything, even more tendentious and loaded than his approach to painting.

As an example, consider his comments on the following passage from The

Red Badge of Courage in which Henry Fleming encounters the body of

a fallen soldier and notes, in Crane's characteristically chilly and ironic

way, the touching pathos of death and of our own bodies:

Once the line encountered

the body of a dead soldier. He lay upon his back staring at the sky.

He was dressed in an awkward suit of yellowish brown. The youth could

see that the soles of his shoes had been worn to the thinness of writing

paper, and from a great rent in one the dead foot projected piteously.

And it was as if fate had betrayed the soldier. In death it exposed

to his enemies that poverty which in life he had perhaps concealed

from his friends.

The ranks opened covertly

to avoid the corpse. The invulnerable dead man forced a way for himself.

The youth looked keenly at the ashen face. The wind raised the tawny

beard. It moved as if a hand were stroking it. He vaguely desired

to walk around and around the body and stare; the impulse of the living

to try to read in dead eyes the answer to the Question.

Fried discusses this passage

in conjunction with two other similar passages from Crane's short stories

and uses it to launch an argument that parallels the one he makes about

Eakins involving the work of art as a site for a drama enacted between

writing and the artist's revulsion from writing. His observations about

it follow:

. . . in the production

of these paradigmatic texts by Crane an implicit contrast between

the respective "spaces" of reality and of literary representation–of

writing (and in a sense, as we shall see, of writing/drawing)–required

that a human character, ordinarily upright and so to speak forward-looking,

be rendered horizontal and upward-facing so as to match the horizontality

and upward-facingness of the blank page on which the action of inscription

was taking place. Understood in these terms, Crane's upturned faces

are at once synecdoches for the bodies of these characters and singularly

concentrated metaphors for the sheets of writing paper that the author

had before him, as is spelled out, by means of a displacement from

one end of the body to the other, by the surprising description of

the worn-down souls of the dead soldier's shoes in the passage from

The Red Badge. (The displacement is retroactively signaled

by the allusion to reading in the last sentence of the second paragraph.)

Thus for example the size

and proportions of a human face and that of an ordinary piece of writing

paper are roughly comparable. An original coloristic disfiguration

. . . by death making [the dead soldier's face] ashen . . . may be

taken as evoking the special blankness of the as yet unwritten page.

. . . [Additionally, the] further disfiguration [of the features of

the face], by the wind that is said to have raised the soldier's tawny

beard (in this context the verb betrays more aggressive connotations

than at first declare themselves) . . . defines the enterprise of

writing–of inscribing and thereby in effect covering the blank page

with text–as an "unnatural" process that undoes but also

complements an equally or already "unnatural" state of affairs.

(It goes without saying that the text in question is invariably organized

in lines of writing, a noun that occurs, both in plural and singular

form, with surprising frequency in Crane's prose, as for example in

the [first] sentence).

It is, undeniably, a virtuoso

critical performance. Fried's tendentiousness carries everything before

it. One admires his ability to marshal his troops so ingeniously and to

remain completely undaunted by conflicting artistic or worldly facts.

In the first place, since he is committed by his argument in advance to

describing the text as a site for writing, it becomes unimportant that

a sheet of paper is not actually comparable in size to a face. (For those

who haven't explored such arcana, I would point out that in my rough reckoning

today in front of a mirror, a face measures approximately only one-half

the size of a sheet of standard typewriter paper, and I would further

add that one of the few facts that we know conclusively about Stephen

Crane's writing is that he used paper that was larger than standard typewriter

size, paper that was approximately legal-sized, making the equation of

the size of the face and that of the paper he used even less apt than

it would otherwise be.)

It becomes further unimportant

that in this passage the face is not metaphorized in terms of the qualities

on would normally associate with a piece of paper (that is to say, it

is not said to be "blank," or even "white," but rather

is called "ashen"), or that the soldier's face and the reference

to paper are not even mentioned in the passage in connection with each

other. Since he is determined in advance to link the blankness of faces

and pieces of paper, Fried can invoke a "displacement" and bravely

move the paper metaphor from "one end of the body to the other."

One's only objection is that in doing it, Fried attributes the movement

to Crane, not to himself. That is what I meant by saying that Fried does

it all. He freely and loosely moves around in the text, and then, by means

of a kind of critical sleight of hand, attributes his movements to the

text itself.

Finally, consider Fried's treatment

of the relationship of the wind and the dead soldier's beard. Crane writes:

"The wind raised the tawny beard. It moved as if a hand were stroking

it." But committed to a rhetoric of disfiguration and violence, Fried

turns this into an observation about "[the] further disfiguration

[of the features of the face] by the wind that is said to have raised

the soldier's tawny beard (in this context the verb betrays more aggressive

connotations than at first declare themselves)." Fried says "in

this context," but one wants to ask in what context? The controlling

context Fried alludes to, the context that shapes his understanding, is

not the context defined by The Red Badge of Courage itself, but

the coercive context of his own argument about the work. The wind's stroking

of the beard betrays aggressive and disfiguring connotations, because

Fried's argument requires them, independently of the passage itself. The

language of the passage itself is, in fact, not "aggressive"

or "violent," but really quite tender and solicitous. In this

case as elsewhere, Fried reveals himself to be as tone-deaf to language

as the worst of the new critics before him. With his sternly cognitive

attention to semantics, he doesn't hear what Robert Frost called the sound

of sense, or he could certainly never treat this passage in such an emphatically

disfiguring way.

Briefly put, the logical fallacy

which allows Fried's interpretive violence to be perpetrated on the texts

he examines involves a three-step process: first he hypostatizes a quality

or aspect of a work or passage (for example, the "threat to vision"

represented by the "disfigured" figure of the mother in The

Gross Clinic); then he hypostatizes another quality or aspect of another

work or passage (the "anarchic" and "incandescent . . .

coloristic explosiveness" of the reds in Will Schuster); and

then he relates the two qualities he has described at a more abstract

level of analysis (in this example, so that Eakins' work is said systematically

to embody a thematics of "violent" and "disfiguring"

repelling of vision). The sleight of hand in all of this is that Fried

is almost always comparing his own terms and observations with each other,

not comparing or relating actual aspects of the works in question. Thus,

as he reiterates on nearly every page of his argument, his observations

at one point repeatedly recall his observations at another. The problem

is that the expressive details of one text very seldom recall the details

of another. In the terms of the above example, the color of Will Schuster's

shirt or the alleged explosiveness of the subject matter in the one painting

does not relate to the pain and grief of the mother in the other painting.

Only the terms describing the two things relate. The argument swallows

its own tail.

After such strictures, I again

want to emphasize how profoundly I sympathize with Fried's critical goals,

if not with his practices. American art criticism must be saved from the

repressiveness of realism and the narrowness of genre criticism or the

texts which are the subjects of its attention will be doomed to trivialization.

Fried is right in arguing that these texts are imaginatively more unstable

and interesting than they have been given credit for being in the past.

The general uneasiness created by his criticism is not that it ferrets

out imaginative disturbances in texts that have none, but that the disturbances

it finds trivialize the texts in their own way as badly as the old realist

criticism did in its way.

Put briefly, the expressive

effects Fried describes in the works he examines are alternately either

too esoteric and technical or too eccentric and extreme to be convincing.

On the one hand, as his concentration on the thematics of writing and

drawing suggests, the meanings he traces are frequently so involved with

the merely technical or formal details of the production of a text that

we are back in the old dreariness of works of art being sterilely about

themselves or their own processes of being created. On the other hand,

the thematics of violence and disfigurement that he attributes to these

texts is so excessive and melodramatic that it makes them apparently speak

only to the most extreme or deranged states of feeling and awareness in

us. In either case the text is made irrelevant to the experience of ordinary

life as it is lived by non-artists (and by artists when they are not actually

creating their works). Or, to put another way, in being melodramatically

trumped up with such crude violences of expression and grand intensities

of conflict, Eakins' and Crane's texts are not enriched, but coarsened

and made, in fact, less interesting, less complex, less nuanced, less

intricately and subtly troubled than they actually are. Though Fried would

probably hate my saying it, the problem is that he makes these texts too

simple.

Fried's criticism lives in

exciting extremes; he gives us stirring contrasts; but what if the truth

of most of our lives–and the lives of these artists too–is that they

are, however sadly, lived in the middle of delicate muddles of feeling

and shaded conflicts of allegiance? But, of course, the exploration of

that middle-kingdom where vision and work, ideals and realities, imagination

and society are not simply opposed, but rather mixed-up and half blended

together then might then become the expressive subject of these works.

Almost nothing Fried describes in these works connects up with or impinges

on the middling, ambiguous, ambivalent conditions of our ordinary experience.

As a result, what one loses

sight of in Fried's analysis is precisely the complex human meanings he

seems so fervently to want to bring back into the works he examines. If

Johns' talking about the "American heroism" represented by The

Gross Clinic insufficiently recognizes the unstable play of imaginative

energies and the conflicts of feeling present in the painting, Fried's

microscopic focus on the importance of the color red, the concealment

of one surgeon's figure, and the figural distortions of the patient's

body makes the disturbances he claims to see in the work seem merely formal

and therefore irrelevant to the practicalities of our daily lives. In

his tendentious discussions of the technical aspects of Eakins' or Crane's

work–like his lengthy attention to the legibility of both artists' handwriting–Fried

neglects the less dramatic, but more engaging realistic narrative interests

that make their texts matter so much to us. In short, if all that Eakins'

and Crane's work tells us is what Fried says they do, just as if all they

tell us is what Johns and Goodrich say they do, they truly doesn't deserve

to have such attention lavished on them.

The task set for American art

criticism in the future will be to find a way to be responsive to the

practical, frequently prosaic, always realistic, human situations and

concerns with which these works obviously engage themselves, without being

repressive of the destabilizing imaginative and emotional energies also

present in the same works. What one searches for is, in effect, a third

position as an alternative to the two I have described–one not captive

to the psychological and social normativeness and narrative neutralizations

of realism, on the one hand, and yet, on the other, one not willfully

reading into the work hermetic formal references or eccentric violences

of expression. Ideally, what one desires is that the critical explanation

should do what Eakins' or Crane's work itself daringly and complexly does–be

connected with the world of ordinary men and affairs and the middling

condition of our lives, even as it simultaneously offers radical imaginative

critiques of all merely ordinary, normative, social understandings of

experience. That is the double agenda that American art–simultaneously

narratively realistic and committed to social forms of expression, yet

imaginatively transcendental and essentially critical of social arrangements

and relationships–has always precariously maintained. It is the double

agenda which has, I suspect, been the source of so much critical confusion

about it.

Excerpted from Ray Carney,

"Crane and Eakins," Partisan Review, Volume LV, Number

3, Summer 1988, 464-473.

To read more about critical

fashions, see the essay "Sargent and Criticism" in this section,

"Capra and Criticism" in the Frank Capra section, and

"Skepticism and Faith," "Irony and Truth-telling,"

"Looking without Seeing," "Art as a Way of Knowing,"

and other pieces in the Academic Animadversions section.

The preceding

material is a brief excerpt from Ray Carney's writing about American painting.

To obtain the complete text of this piece or to read more discussions

of American art, thought, and culture by Prof. Carney, please consult

any of the three following books: American Vision (Cambridge University

Press); Morris Dickstein, ed. The Revival of Pragmatism: New Essays

on Social Thought, Law, and Culture (Duke University Press); and Townsend

Ludington, ed. A Modern Mosaic: Art and Modernism in the United States

(University of North Carolina Press). Information about how to obtain

these books is available by clicking

here.

|