|

The

most important illustration of Cyril and Shirley's receptivity to different

ways of being, feeling, and thinking is their openness to each other's

differences of opinion and point of view. It is central to Leigh's imagination

of Cyril and Shirley's relationship that they don't necessarily

agree or see things the same way. Their relationship is woven out of differences.

The differences may be comical (as when they give Wayne contradictory

directions on how to get to the cab stand–in a scene that is probably

indebted to the comical disagreement about which way is East and which

is West in Ozu's Late Spring), semicomical (as when they briefly

spar over whether they should go to Valerie's party), or deadly serious

(as in their feelings about having a child), but they are honored, respected,

and dealt with–not denied, suppressed, or erased. The

most important illustration of Cyril and Shirley's receptivity to different

ways of being, feeling, and thinking is their openness to each other's

differences of opinion and point of view. It is central to Leigh's imagination

of Cyril and Shirley's relationship that they don't necessarily

agree or see things the same way. Their relationship is woven out of differences.

The differences may be comical (as when they give Wayne contradictory

directions on how to get to the cab stand–in a scene that is probably

indebted to the comical disagreement about which way is East and which

is West in Ozu's Late Spring), semicomical (as when they briefly

spar over whether they should go to Valerie's party), or deadly serious

(as in their feelings about having a child), but they are honored, respected,

and dealt with–not denied, suppressed, or erased.

Notice the contrast Leigh

sets up with the other two couples. Valerie's forced chipperness

and patronizing knowingness is a denial of otherness, glossing over

and ignoring the gap that separates her from everyone around her.

In the case of Rupert and Laetitia, when Rupert has different opinions

than Laetitia (as in their brief discussion of the opera), they

vie for domination, with her ultimately winning the argument and

converting him to her point of view. A monotonic universe dictates

zero-sum games: When there are two views of anything, one must be

right and the other must be wrong. One person must win and the other

lose. They can't even tolerate, let alone make something of their

differences, which is why their disagreements lead to awkward silences

or the breaking off of relations altogether (as in the scene of

Valerie's breakdown).

Cyril and Shirley live

in a more multivalent world–a place where different ways of understanding

and points of view can coexist. When they disagree about directions

to the cab stand, whether they should attend Valerie's party, or

visit Mrs. Bender, they don't attempt to argue each other into submission,

but enter into the other's perspective, which is why their differences

ultimately lead to discovery. In the process of comparing their

differences (and not always joking ones) and staying open to each

others' points of view, Cyril and Shirley learn and grow.

That is ultimately what

the "died with his boots on" bedtime scene–one of the

greatest in all of Leigh's work–illustrates. Cyril and Shirley's

relationship is stunningly complex and mobile. (It would hardly

be an exaggeration to say that there are more emotional shifts and

tonal adjustments in the five-minute sequence than in many entire

movies.) Note not only how the two lovers turn the moment into a

dramatic skit but how rapidly and supplely they respond to each

other's lead–sometimes following the other, at other times taking

things in a whole new direction. Tonally and emotionally, the sequence

is one of the most nimbly inventive interactions in all of Leigh's

work.

To mark how far we have

come imaginatively since Bleak Moments, one only has to compare

the litheness of Cyril's and Shirley's play with the angularity

of Pat's and Hilda's or the clumsiness of Sylvia's and Norman's.

Or, in terms of the relationship of lovers, note how much quicker

and more supple the changes in this sequence are from Ann and Naseem's

improvisation in Hard Labour (employing the concept not to

describe the trivial improvisations of actors making up their lines,

but the profound improvisations of characters adjusting their relationship).

The scenes in the earlier works are recognizably from the same hand

that created the interaction between Cyril and Shirley, but in this

film it is a hand (and eye and ear) far more delicate, quick, and

aware. As often happens in a dramatic career, Leigh's characters

grow in their sensitivity as he grows in his ability to depict it.

His possibilities of expression create their possibilities of awareness,

which in this case are breathtaking in their range and movement.

(The stage play, Ecstasy, seems to me to be the turning point

in this regard.)

Shirley begins by wittily

casting Cyril and herself as characters in a Western. ("'E

died with his boots on!") Cyril picks up on her reference and

mock-chastises himself for getting so drunk. ("He was too pissed

to take them off.") Shirley sidesteps the self-criticism to

assume a nurturing stance ("Do you want me to 'elp yer?").

Cyril responds with gratitude ("Oh, yeah."). Responding

to Cyril's concession and taking a beat to mark a playfully dramatic

shift of tone, Shirley turns jokingly extortive. ("What'll

you gimme first?") Cyril plays desperate. ("Anything.")

Given the degree of Cyril's abjectness, Shirley decides to push

her advantage with a humorously threatening warning. ("Anything

I might 'old you to that.") In response, Cyril plays at being

so needy that he will agree to anything. First, he downright grovels.

("You name it!") Then expresses exaggerated gratitude.

("This is bloody good of you.") Given his earnestness

and abjectness, Shirley, having triumphed, now relents from her

threat and playfully transforms herself from mate in one sense to

mate in another. ("Don't mention it, old chap.")

Once the power struggle

is over and they are in a comfortable place, Shirley morphs into

a mommy singing a children's ditty. Cyril is her little boy. ("Unzip

a banana.") Mum then gives way to mock-critical outsider clucking

over Cyril's infantilism. ("His mum never showed 'im 'ow to

undo 'is laces.") As if to assert his masculinity in response,

Cyril switches his tone to generic tough guy. ("Give it a good

tug.") But Shirley rejects a partnership with Jimmy Cagney

and chooses to turn the interaction in a tender direction. ("Oh,

I was going to ease it off.") But, as if not wanting to get

too far imaginatively from Cyril, her next line comically reestablishes

solidarity with his "macho man" stance by inflecting the event in

a playfully sexual direction. ("I'll tell you what. If I can't

ease it off, I'll give it a good tug.") The tug itself is played

for comedy, as Shirley takes a pratfall backward and she and Cyril

share a good laugh. The comedy then gives way to the playful sexuality

of Shirley's next question. ("Did you come?"), before

she then morphs back into mum again, playing a game of "This

little piggy went to market" on Cyril's toes.

That's less than half

of the scene, which continues on beyond this point, but it should

be sufficient to indicate not only the emotional fluidity of the

interaction, but the differences in the two characters' "voices."

The interest is the concordia discours. (Shirley is flirtatious,

romantic, and warm; Cyril full of sexual swagger and bravado. She

is maternal, giving, and vulnerable; he is cool and laid-back. While

sex is linked with nurturing and motherhood for her; it connotes

lust and eroticism for him. While she thinks of future consequences

like children; he focuses on immediate pleasures.) The differences

are not treated as something to be resolved or ignored or glossed

over but as a play of countercharged energies that allow the characters

to make something larger than either could alone, to make something

valuable for both them and to us.

The reason we know that

Leigh is not asking us to take sides for or against Cyril and Shirley's

different ways of expressing themselves (or, thank goodness, editorializing

about a "failure of communication") is that their voices

work so beautifully together, playing off each other so stimulatingly,

creating something greater than either could ever achieve alone.

Cyril and Shirley function

like dancers who demonstrate that a great pas de deux is made not

by mirroring the other's movements, but out of sexual and emotional

differences. The ideal partnering is one that trusts the other enough

to allow each to move somewhat independently of (and, if need be,

at odds with) the other. The greatest drama doesn't come out of

merging, compromising, or blending individual points of view, but

from honoring and bringing the differences into contact with each

other.

To shift the metaphor

to the art that Rupert and Laetitia show themselves incapable of

appreciating, the effect is like an operatic duet in which two singers

perform separate but intertwining melodies–vocally merging, separating,

and merging again. They remain in sensitive relation to each other,

even as they assert their differences from one another. The interaction

is what makes the duet so great.

How different are Rupert

and Laetitia's disharmonies in their bedroom scene! Their voices

have a formulaic weariness, as if they were not even listening but

only going through the motions of pretending to converse. (The nagging,

insistent tedium of some of Laetitia's final remarks summarizes

the tonal effect: "No, darling, how many times? Is my neck

looking a little saggy? Do you see any lines? Darling! I thank God

every day I've been blessed with such beautiful skin: you really

are a very lucky boy. You take me for granted.") Rupert and

Laetitia's voices, identities, moods, and positions are the opposite

of responsive. They are frozen in place, fact trivially expressed

by Laetitia's physical position and her reference to the coldness

of Rupert's hands, but profoundly captured by the iciness of her

tones and the fixity of the her and Rupert's imaginative positions.

The issue of what to

make of your emotional and intellectual differences runs through

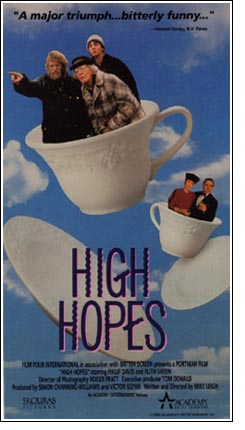

scene after scene in High Hopes, starting with the very beginning

of the film when Cyril brings Wayne upstairs to see if Shirley can

help him with directions. Cyril and Shirley's slightly different

responses to the same basic situation create a delicately comic

interaction. Shirley is kinder and more caring (she invites Wayne

in, asks him to sit down, offers him tea); Cyril is more factual

and intellectual (he hits the street-index book). She is more personal

and hospitable (attempting to put Wayne at ease by humorously introducing

him to her cacti); Cyril is more cynical, self-referential, and

abstractly ideological (making a series of sardonic political and

economic allusions). Which response is right? Which point of view

is the best? There is no right or wrong. (This is not an American

movie.) The point is not to have to choose between Shirley's

ways of responding and Cyril's but to understand that the play of

differences is what makes for interest in both art and life....

–Excerpted from Ray

Carney, The Films of Mike Leigh: Embracing the World (London

and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

|

|

Ray

Carney's The Films of Mike Leigh is quite simply the

best book of film criticism I have ever read.

Now I have to say

that I have never read any of Carney's other books (he has

also written books on Cassavetes, Frank Capra, and Carl Dreyer),

which, for all I know, might be even better. But as a friend

of mine put it, 'His writing blows everything else out there

away, even to the point of many times seeming like simply

in a class of his own...different in kind more than degree.'

And although I admit to not having read 'everything else out

there,' I feel the exact same way. Ray Carney's new book has

undeniably rocked my world.

Ray Carney's book

is to what usually passes for film criticism what Mike Leigh's

movies are to what, in Hollywood, usually passes for filmmaking:

a truly radical critique, a whole different animal, and a

solitary voice of sanity that has somehow miraculously managed

to make itself heard over the noise and hullabaloo of this

culture's present-day insanity. |

|

–Caveh

Zahedi, creator of A Little Stiff and I Don't Hate

Las

Vegas Anymore,

in a review in Filmmaker Magazine |

| |

|

| |

Mike Leigh’s work is difficult to pin down. Echoing what Ray Carney says of Leigh’s more blinkered characters, examining these films becomes a lot murkier when you bring too many ideas and film-critical categories to bear. Although not without its strengths and serendipities, Garry Watson’s book suffers from intellectual larding while, like one of Leigh’s more far-sighted characters, Carney and Quart’s gets in amongst the rough-and-tumble....

The Carney and Quart book was the first critical study of Leigh’s work and every subsequent book on Leigh must negotiate its rigor and insight. I have yet to read a book that better approximates my experience of watching Leigh’s films.My one regret is that, apart from the important BBC plays Nuts in May and Abigail’s Party (1977), I have yet to see many of the early works wherein Carney locates the wellspring of Leigh’s improvisatory power and vision.

Animating this study is a distinction between two types

of Leigh characters that resonates culturally, politically and

spiritually across his work. For Carney, there are those like

Rupert and Laetitia Boothe-Braine in High Hopes (1988),

Nicola in Life Is Sweet (1990), and Sebastian in Naked (1993)

who, mired in a mental image of themselves, pigeon-hole

others in prejudices, effectively foreclosing on generous and

responsive solidarity. Then there are those like Cyril and

Shirley in High Hopes, Wendy in Life Is Sweet, and Louise in Naked who have all the foibles, strengths, and self-doubts of

their humanity, and are open to the flows of human interaction.

Alison Steadman’s giggly and affectionate Wendy still

epitomizes the principle of social cohesion in Leigh. It is perhaps

unsurprising that Steadman and Leigh were married,

while the positive response to the density of experience recalls

the thick descriptive methodology through which a Leigh

film is arrived at. Evoking the Dickensian and Lawrentian

views of human sensibility (as Watson points out), Leigh feels

that the individual mindset has consequences for the wider

culture, and by this light the generous impulse in Wendy and

other Leigh characters has been eroded by consumerism and

social mobility in postwar Britain. Not as overtly political as

Ken Loach, Leigh has nevertheless chronicled the domestic

consequences of the decline of the social consensus imagined

by writers from Dickens to George Orwell.

One of the most unexpected aspects of Carney and Quart’s book is the way it puts mainstream American cinema in perspective by comparing it with Leigh’s cinema.With his focus on characters as mannered and tic-ridden “outsides” (as opposed to Hollywood’s granting us access to Forrest Gump’s inner kindness despite the goofy exterior), Leigh charts that elusive quality, the “ordinary” moment—the everyday drama of interaction they never show in Hollywood because it occurs between the heroics.

In doing so, Carney shows, Leigh pulls apart the Enlightenment model of agency and volition on which most American movies depend. Recalling classes he has taught—he is Director of Film Studies at Boston University—Carney describes how Americans are often perplexed by a cinema in which nothing seems to happen. But Leigh’s drama of transformation is rooted in the layered rehearsal of interpersonal dynamics observed with the patience of a European Ozu. Whilst British Leigh commentators have been preoccupied with the writer-director’s purchase on the sociological landscape, Carney convinces us that Leigh and Ozu share a feeling for the interplay of performance and mise-en-scène which moves beyond David Bordwell’s pioneering Ozu dichotomy between modernism and tradition. Leigh’s conception of experience (unlike that of Hollywood) is durational rather than deadlined, heterogeneous rather than hurried. Carney’s examination of space and time in Leigh reveals, as Bordwell has done elsewhere, that the mainstream model of experience conceals as much as it reveals.... |

| |

–Richard Armstrong, a review of Gary Watson, The Cinema of Mike Leigh and Ray Carney and Leonard Quart, The Films of Mike Leigh: Embracing the World, published in Film Quarterly, Dec 2005, Vol. 59, No. 2, pp. 62-63 |

| |

|

| |

No other study sheds such a revealing light on Leigh's background, his influences, his emotional groundings, and, of course, his unique cinematic sensibility....[Carney's The Films of Mike Leigh is a] powerful and multifaceted analysis which welcomes, like Leigh's work, the vibrant eye and the uncalcified consciousness.

|

| |

-- Andrew Hamlin, in a review of Ray Carney's The Films of Mike Leigh: Embracing the World, published in MovieMaker Magazine. |

| To learn

how to obtain this book, click

here |

|