I do not care for movies

very much and I rarely see them; further, I am suspicious of criticism

as the literary genre which, more than any other, recruits epigones,

pedants without insight, and intellectuals without love. I am all the

more surprised, therefore, to find myself not only reading your film

critic before I read anyone else in your magazine but also consciously

looking forward all week to reading him again. In my opinion his column

is the most remarkable regular event in American journalism today.

–W. H. Auden

The year was 1944, the journal

The Nation, and the critic James Agee but Auden's letter to the

editor sums up much of the love-hate relationship felt by most readers

of film criticism ever since. It points up the paradox that riddles all

writing on film: there is no writing capable of being at one moment more

exasperatingly infantile, personal, and polemical, and at another, more

excitingly impassioned, probing, and free of the usual cant of academic

criticism. And probably as much because of the one propensity as the other,

film criticism has become the most successful cottage industry in the

marketplace of ideas. Not even the lit. crit. business has grown faster,

or prospered more in our inflated intellectual economy in the last ten

or fifteen years. And yet, for a variety of reasons, no regular criticism

has succeeded in remaining more damnably, more blessedly, more unpredictably,

amateur in practice.

Which is to say, film writing

has almost succeeded in resisting institutionalization. Perhaps its practitioners

have been just too independent and principled to affiliate themselves

with a particular editorial, commercial, or academic point of view. Or

perhaps they are just too quirky and naive. But if film writing is refreshingly

exempt from routine institutional controls on forms of discourse, it also

pays the price of all unsupported, unsanctioned relationships. Scrupulousness

honesty, and care are rare enough in any relationship between a writer

and his readers; cuteness, casualness, and breeziness always beckon as

easier ways to bring off an affair. If the short term and the immediate

impression are all that count in a review, they are temptations almost

impossible to resist.

If one wants proof of the ability

of film criticism to avoid institutionalization, one has only to look

at Time and Newsweek, the two most influential molders of

general film opinion today. For anyone familiar with the Byzantine editorial

attitudes and practices at either magazine, the pleasant surprise is that

individual film critics "exist" at all. The editorial bureaucracies

at both magazines labor to absorb the sounds of particular writers into

the monotone of their controlling corporate styles and tones. And they

are far from unsuccessful. One remembers that a Mr. James Agee was writing

a weekly column of film drivel for Time, in the best brisk and

punny Time-ese style, the same year Auden was praising his writing

in The Nation.

Many of the reviews and reviewers

at both Time and Newsweek are indistinguishable, of course.

They pretty much blur together in the low drone of the standard news magazine

brief review form. It is a structure pre-fabricated from a smattering

of plot summary, a few descriptive superlatives (it's indifferent whether

they praise or damn, just so they are superlatives), and a two or three

sentence exhortation to the reader to attend or abstain–all expressed

as chattily, flashily, and cleverly as possible.

But at Time Richard

Schickel and Richard Corliss succeed in making themselves heard above

that general hum–if only what they managed to articulate were more valuable.

Both men have produced some fine critical pieces before their tenures

at Time (so did Agee), yet there is little here to show it. Corliss's

favorite rhetorical tactic is what in my college days used to be called

the strategy of the "Overwhelming Equivocation." The goal is

to allow the writer to have all things all possible ways, at the least

possible discomfort to the potential reader. What would he get for this,

his summary paragraph on Woody Allen?

Some moviegoers will see

the film as life made into art.... Others will wonder if the movie

isn't an elaborate mechanism of self-abuse...."Stardust Memories"

has much to please the eye and ear.

Not bad, but anyone above a

freshman might be expected to equivocate more cleverly. This use of subjunctives

and indirect discourse is really quite primitive. Compare the following

yoking of disparate materials together. It might work in an essay on metaphysical

poetry:

In "Honeysuckle Rose"

the romantic charge is as strong as any pairing since Leslie Howard

and Ingrid Bergman–or at least since Kermit and Miss Piggy.

There's no point in multiplying

examples. I only include the above quote because every time I read it

I have to remind myself that it is not a parody of Corliss's ambidextrous

exaggerations; it is Corliss himself. The writing is impervious to parody.

To be vulnerable to mockery a writer must have at least a strain of conviction

in him. Corliss's tongue is always too far in his cheek to be guilty of

that.

Richard Schickel is a sadder

and more interesting case, if only because he seems less capable of Corliss's

self-protective cynicism. All Schickel can muster up in his reviews is

his own disappointment and weariness with his weekly task. Admittedly,

the four or five films a reviewer might see during a typical week are

not among the most astonishing achievements of the human spirit; but that

there are interesting moments in the most ordinary of films, and that

occasionally quite extraordinary films get released, are things that a

reader would never guess from Schickel's wan, discouraging prose. Corliss's

brazen evasiveness is finally less saddening than Schickel's fainthearted

praise. It is as if current films were all such con games for Schickel

that his only function can be to give the prize to the superior con man:

"Director Guy Hamilton has a gift for moving this sort of nonsense

right along." The most excited he can get about a particular film

is that one movie is "jolly," another "a mature exercise

in style," a third has a "pleasant Iyricism," and another

is "an amiable entertainment"; he works up as much passion as

if he were writing about a pet show.

Of course the value of making

one's praise indistinguishable from one's pan is that it absolves the

reviewer from the burdensome analysis of his own dissatisfactions. After

a few token objections to "Hopscotch," Schickel can finesse

the rest of the review with a piece of cinema-weary double-talk like the

following: "Still Matthau is Matthau . . . he does what a star must

do: he creates the illusion that this film is better than it is. He also

makes it look easy."

One is tempted to accuse him

as he accuses the director of "Scum": "This is just another

use of a genre that movie makers love because it is an easy one in which

to make vaguely anti-authoritarian gestures without straining very hard

for originality or for fine moral discriminations."

That is exactly what film reviewing

is for Schickel. His dissatisfaction with almost everything he reviews

is meant to assure us of his intelligence and discrimination; his superiority

to the films he discusses saves him the bother of having to demonstrate

either.

Maybe it is Time's high-toned

CINEMA rubric that afflicts Corliss with such fear of interpretation and

Schickel with such infinite resignation; but for whatever reason, Newsweek's

two regular MOVIE reviewers bring a happy liveliness to their work

almost entirely lacking in Time. Unfortunately, one of them, Jack

Kroll, compromises any capacity for discrimination by blending People

Magazine-style celebrity interviews with his regular film reviews.

The result is a conflict of interest: When a review of "Ordinary

People" metamorphoses halfway down the second column into an interview

with director Robert Redford, one doesn't need to read any further to

know that no hard analysis of the film will ensue. Kroll is one of the

three or four most frequently quoted reviewers in film advertising–always

a dubious distinction–and it should come as no real surprise that a writer

so gushy and quotable should see no difference between film reviewing

and Hollywood hagiography.

One begins to wonder if the

very form of the typical newsmagazine review dooms its authors to vapidity.

The reviewer's "instant analysis" can never express the least

doubt or puzzlement. It is forced to be ahistorical, to avoid all film

terminology, however basic; and it is entirely self-contained, preventing

any possibility of a series of individual reviews in which to conduct

a longer, more complex argument. It is compelled above all else to be

clever and perky. One begins to wonder if anyone could successfully pull

off this task when along comes David Ansen of Newsweek to prove that neither

the mediocrity of the average film nor the constraints of the weekly review

format are responsible for the failures of Schickel, Corliss, Kroll, and

company.

Compare Kroll's (eminently

quotable) substitutions of adjectives for thought with Ansen's measured

syntax, carefully engaged in questioning, testing, and qualifying received

categories:

"Willie and Phil"

is a film largely devoid of ideas (unlike "Jules and Jim");

like his characters, Mazursky puts more stock in feelings. Here the

satirist of "Bob&Carol&Ted&Alice" has given

way to the celebrant.

But he hasn't lost his sense

of humor or his uncanny ability to take the most familiar ethnic stereotype

and give it a twist that makes it fresh. "Willie and Phil" is

crammed with wonderful details ....

But it is on the shoulders

of Ontkean, Sharkey and Kidder that the film stands or falls. Of the

three, Ontkean is the most conventionally likable, the most glamorous–yet

his Willie, the narcissist, is the one whose vagaries try our patience

the most. Kidder, with that slight feral curl to her lip, and Sharkey,

a furiously aggressive actor, don't conform to traditional romantic

expectations. Still, Sharkey's prickly energy becomes comically endearing,

and Kidder's performance sneaks up on you, burrowing deeper as it

goes.

Though the final few sentences

show that Ansen hasn't yet succeeded in freeing himself from certain annoying

metaphoric mannerisms that give more evidence of cinematic fancy than

imagination, until the continuously qualified progress of this analysis

testifies to a care, tact, and respect for the object of his commentary

But Ansen isn't good reading

on only so-called serious films. Even when he is writing about Blake Edwards's

"10," a film that invites dismissive noises from the Cinema-as-Art

crowd, Ansen can use his review to comment on the surprising earnestness

of its comic plot, and even dare to argue its superiority to higher-class

soap operas like "Loving Couples." And when reviewing the disastrous

uncut version of Cimino's "Heaven's Gate," about which most

other reviewers are merely abusive, Ansen attempts to understand some

of the reasons behind Cimino's failure, and to locate telltale signs of

his present weakness in his previous successes. In short, in this world

of once a week, five hundred words or less flash and trash, Ansen with

his prose of connections, discriminations, and measurements, is single-handedly

re-inventing the possibilities of the form.

To turn from the ability to

influence the box office of a film already in general distribution to

the ability to affect whether a film will get a general distribution,

it is no exaggeration to call the New York Times's film pages the

most powerful and decisive critical voice in the country. Not only is

the Times the first place many small budget studio films get reviewed,

but it is almost the only organ of criticism that can give any review

at all to most of the museum and cinema society festivals (featuring independent

or foreign productions) that take place in New York. All this makes Vincent

Canby, the chief priest of this critical Delphi, a man to be reckoned

with. As first-string critic at the Times for the past decade Canby

has the same quasi-official status in the world of film as his colleague

James Reston has in affairs of state–not merely reporting and evaluating,

but helping to create and shape events. It might be flattering to Canby

if the analogy continued beyond the resemblance, but the James Reston

of film criticism is afflicted with a moral amorphousness and intellectual

incoherence that could never pass muster in the op-ed column of his colleague.

In the brief installments of

his daily film reviews and Sunday "Film View" columns, Canby's

writing seems so innocuous and cryptic that it is hard to form any distinct

impression of it at all. At first, among the hysteria and tendentiousness

of so much other writing on film, Canby passes for the one sane, sociable

soul. But it is only after sitting down to breakfast with him over a year

or two that a disturbing pattern begins to emerge in this fog of mild

agreeability. One is first struck by how much less there is to his reviews

than meets the eye, then by the true deviousness of his rhetorical strategies,

and finally, by how masterfully coy, smug, and irresponsible this most

privileged of critics can be.

It isn't only that half of

his film comments are of the "it tingles the spine" and "tears

the screen to bits" variety (I wish I were making these phrases up,

but both come from the same review of "Nashville"), but Canby's

problem is larger than a merely fashionable critical impressionism. He

is the master of a Big Think critical prose that conveniently evaporates

exactly at the points where it is about to commit itself to something.

Follow, if you can, the course of this sentence from a review of "Amarcord":

"'Amarcord' has close associations with Mr. Fellini's last two films,

'The Clowns' and 'Roma,' both memoirs of a sort...." One is prepared

for an exploration of Fellini's fascinating senses of biographical and

cinematic time; one is perhaps prepared for an even more ambitious series

of speculations about the relation of personal, cultural, and even geological

memory in Fellini's films; but the one thing one is not prepared for is

Canby's convenient conclusion to his sentence: ". . . but the likeness

turns out to be superficial on closer inspection." It is a "closer

inspection" that never takes place. This is not a sentence that belongs

to a film review, it is something one says over drinks at a party, as

a form of one-upmanship and chit-chat. The speaker wants credit for asserting

something which he is not only incapable of defending, but, when challenged,

claims the prerogative to unsay. In review after review Canby writes and

then unwrites himself like this, getting full credit for all possible

perceptions and every mutually exclusive attitude.

Sometimes Canby's unwriting

of himself can be quite clever, as when he praises "The Godfather"

as "a superb Hollywood movie," which, in case we don't get the

force of these two quite different adjectives, is explained in the last

sentence of the review, when he calls the film "one of the most brutal

and moving [signs of waffling already creeping in] chronicles of American

life ever designed [and watch what happens here] within the limits of

popular entertainment."

Canby has boasted that copy

editors keep their hands off his stuff, and so thoroughly does he appear

to have everyone around him buffaloed, that one wonders if anyone at all

reads his copy before it is printed in "the newspaper of record."

Certainly a competent editor couldn't have thought anything was actually

being said in impressionistic mumbo jumbo like the following on Lina Wertmuller:

I don't want particularly

to defend "Seven Beauties" here. Though it's a film I admire

tremendously, I do not think that one of its faults is not that it

has a message, but that it has too many. They aren't messages,

really, they are associations that are made with the Wertmuller

material, and sometimes they are quite contradictory. They are disorienting

. . . though I'm not sure that says as much about the movie as about

me, about my wishes, needs, desires to look beyond the immediate image,

and most of the time when you do look there's nothing to see.

Who is being "contradictory"

and "disorienting" here? This is a writer so complacently awash

in the sea of his own exquisite sensibility, and so obviously fond of

his ruminations, that it doesn't matter to him what he says or fails to

say. The reversals and qualifications in David Ansen's writing are an

attempt at sorting and measuring, at finding adequate verbal forms for

a largely non-verbal experience; but Canby's syntactic conundrums simply

communicate his love of riddles, his private delight at the dizzying intellectual

heights to which paradox, ambiguity, and imprecision can transport him.

One of his most serviceable

sorts of paradoxes is that dreary old "form" versus "content'

antithesis. So many films and performances are praised not for "what

the film (or performance) does, but for how it does it," that when

Canby reverses the formulation in an evaluation of Robert De Niro's acting

in "Taxi Driver"–"a performance that is effective as much

for what Mr. De Niro does, as for how he does it" one hardly pauses

to ask might it be a misprint or a slip of the pen. How could it possibly

matter? Once one has graduated from Method Acting 101, what's the difference

between what an actor does, and how he does it?

It would be easier to overlook

these incoherencies and lapses of logic if Canby the neo-Platonist hadn't

projected his own intellectual untidiness into an aesthetic ideal. He

translates his own penchant for disjointed, incoherent critical impressionism

into a general aesthetic theory that, not unexpectedly, exalts disjointed,

incoherent cinematic impressionism, and calls the whole thing "The

New Movie." Although "The New Movie" is mentioned, or alluded

to, in dozens of reviews it's not surprising that "The New Movie"

is described, defined, or analyzed no more carefully than anything else

in his columns. The following passage, from a piece five or so years ago,

is to my knowledge his most extended attempt at articulation. In this

hodgepodge of over-simplifications, half-truths, and gnomic nonsense (all

apparently meant to be insulated from criticism by the jokiness of Canby's

tone), are all the inconsistencies, incoherencies, and hollow rhetorical

flourishes that run through the analyses of individual films:

Today's movies–not all

of today's movies, just a tiny but important minority of today's movies–are

hard on people who were brought up knowing that movies were supposed

to be fun because they were a lesser form of literature that could

be understood even if one didn't know how to read.

In pre-television days

one went to the movies as a kind of reward, as a means to relax, having

finished real, serious work, including all sorts of difficult, often

boring, required reading. Movies were to be perceived in predictable

ways. One could be sure that when one entered a dark, popcorn-scented

movie house there was little chance of being hit with Pascal's "Pensees."

What ideas movies had were spelled out in pictures, which guaranteed

they would never be very complex. Movies had beginnings, middles and

endings, and unhappy endings were just as upbeat as the happy ones.

Heroes never died in vain. In movies, life had shape.

Today's movies are different.

They are not necessarily better, but they are decidedly different

and that difference is alienating a lot of moviegoers who want movies

to keep their old place. There is nothing worse than an uppity movie....

The New Movie is not new, of course. It's been around for years, regularly

since the early 1960's....

New Movies can't be read

like books or road maps. The New Movie talks back to our prejudices

without our knowing it.

As soon as one tries to apply

such a formulation to "old fashioned" directors like Murnau,

Dreyer, Von Sternberg, Renoir, and DeSica, the fatuousness of the whole

game becomes apparent. "The New Movie" is simply whatever Canby

needs it to be at the moment, a stick of incense he can burn whenever

his favorite reductive formulations– this movie is "about,"

"says," or "tells us"–predictably fail him for the

umpteenth time.

It's not really surprising

that vagueness and incoherence should become such virtues for a writer

for whom the virtues of films are so vague and incoherent. Consider the

raised dots that punctuate the above quotation, and about half the pieces

Canby writes. They are but an admission of Canby's unwillingness (or inability)

to sustain a coherent, continued analysis for even the length of his column.

Perhaps he thinks his reviews are imitating the fragmented "New Movie"

he is forever heralding and never defining. But it is more likely that

Canby simply cares so little about a sustained analysis that he sees nothing

peculiar in fragmenting even something as fragmentary as one of his reviews.

But the point is, of course, Canby's aesthetics notwithstanding, that

the "what" of a critic's performance is never separable from

the "how."

I want to pass more briefly

over three critics for smaller publications: John Simon at The National

Review, Robert Hatch at The Nation, and David Denby at New

York Magazine.

Simon is the Polonius of film

criticism, apparently able to sit through the dazzling human complexity

that the experience of even an average film provides, and emerge absolutely

untouched and unscathed, still clutching the morality play meanings with

which he entered. It is no accident that Shakespeare made his most proficient

moralist also his coldest, most literal-minded character. Like Polonius,

Simon's most amazing skill is his ability to avoid an imaginative or emotional

experience even when it is thrust upon him, and like Shakespeare's supreme

literalist, he is actually not bad (and is certainly quite comfortable)

when dealing with matters of fact, and can write an occasionally interesting

dissection of a documentary or an historical drama. But put him up against

an imaginative experience that requires some surrender of his own categories,

some vulnerability to human complexities that defy moralization, and all

he can do is find fault with some illogic or inconsistency in the plot,

some inaccuracy in the costumes, sets, or script. If human relationships

and meanings were generated out of facts and events as simply and straightforwardly

as Simon would have them, there would be no Hamlets and Shakespeares,

no films, and none of the mysteries and confusions in our lives that keep

us sitting through them.

If Simon can't let go of his

judgments and beliefs about the "real world" long enough to

be affected by the imaginative world of a film, Robert Hatch puts up no

resistance at all. Every film sweeps him away and dissolves him in a sea

of impressions and associations. Of the opening of "Kagemusha,"

he writes:

Looking at the three [men]

seated there, I thought, "porcelain" and as the movie progressed

I fancied myself in a museum collection of Japanese ceramics, in the

hundreds, sprung from their cases and swirling around me in a tumultuous

masque.

Simon refuses to allow a film's

style to bring into existence a reality at odds with his sternly pragmatic

one, Hatch apparently never even asks that a film have anything at all

to do with his experience of life. As the metaphors in this quotation

suggest, films carry us gloriously away from the messes of life, into

a land of reverie, dreams, and Art with a capital A. And the inevitable

result is the paralysis of any capacity for judgment or discrimination

in the critic. How can one judge a daydream? Film becomes essentially

escapist, and consequently frivolous. It is an art of "as if,"

and Hatch's tone becomes equally "as if," until his reviews

read like exercises in the subjunctive. Facts, certainties, and realities

disappear in a swirl of possibilities and suppositions: "It is said

to be...." "I doubt that it...." "It is possible that...."

Hatch is forced into the ultimate tonal absurdity when, faced with a film

he really wants to dislike ("Dressed to Kill," in this case)

he is only able to "deplore its jolly attitude toward mad killers."

Even Simon's wooden headshakings and homilies seem preferable to this

moral Epicureanism.

After being forced to choose

between sermons and flights of fancy, it is positively exhilarating to

come upon David Denby who is able to turn his considerable analytical

powers on the immense complexities of the experience of watching a film.

Denby joined New York not long ago with the departure of Molly

Haskell. Like David Ansen at Newsweek (another Boston-trained critic)

he realizes that the last thing a reader needs or wants is one more regurgitation

of the characters, plot, and themes of the latest Altman, Coppola, or

Allen.

Denby's chief shortcoming

is that he at times seems a little too eager to be sufficiently light,

bright,

and gay, and a bit too fond of Kaelian metaphoric pyrotechnics even when

they are at the expense of the film he is describing. But these things

acknowledged, there is no critic now writing who is better at discussing

all of a film–its plot, characters, politics, aesthetics, editing,

photography, and sound track–not as a historical or moral document

as Simon might have it, nor as a platform for free associations and frissons ý la

Hatch, but as a fiction, a man-made thing, a humanly arranged event.

On "Coal Miner's Daughter," Kubrick's "The Shining,"

Redford's "Ordinary People," Allen's "Stardust Memories,"

and others, Denby is exemplary. While Hatch and Simon are busy making

facile connections between some superficial event in a film and a particular

social fact or psychological association, Denby describes and evaluates

the deep structures that make a film's meanings possible, interesting,

or compelling. While Simon and Hatch are assuming the simplest imaginable

correspondences between the "intentions" of directors, performers,

and technicians, and their finished products, Denby is redefining the

nature of intentionality in an art as complex as film. He is tracing

out the connections between the deeper structures of significance and

the

contributions of particular workers, locating their "intentions"

not behind, anterior to, or outside of the film, but as they are built

into the cinematic arrangements of every work. There is no more impressive

example of the proper function of criticism.

I've saved the three most senior,

crotchety, and controversial critics for last. Pauline Kael, Andrew Sarris,

and Stanley Kauffman are arguably the three most influential critics writing

on film today because they are the writers other writers read. Of the

three, Kael of The New Yorker is indisputably both the best known

and the most controversial. In Kael's writing, objects are taken to pieces,

and personalities are dispersed not by virtue of some stylistic trick

or sloppiness, but as part of a radical redefinition of cinematic syntax

and meaning. Kael is a critic in the tradition of the Susan Sontag who

wrote in "Against Interpretation":

It may be that Cocteau

in "The Blood of a Poet" and in "Orpheus" wanted

the elaborate readings which have been given these films, in terms

of Freudian symbolism and social critique. But the merit of these

works certainly lies elsewhere than in their "meanings."

Indeed it is precisely to the extent that . . . Cocteau's films do

suggest these meanings that they are defective, false, contrived,

lacking in conviction.

From interviews, it appears

that Resnais and Robbe-Grillet consciously designed "Last Year

at Marienbad" to accommodate a multiplicity of equally plausible

interpretations. But the temptation to interpret "Marienbad"

should be resisted. What matters in "Marienbad" is the pure,

untranslatable, sensuous immediacy of its images....

Again, Ingmar Bergman may

have meant the tank rumbling down the empty street in "The Silence"

as a phallic symbol. But if he did it was a foolish thought.... Those

who reach for a Freudian interpretation of the tank are only expressing

their lack of response to what is there on the screen.

No one has made more of a career

of "responding to what is there on the screen" than Kael. Her

criticism is a fulfillment of Sontag's effort to bypass the normal structures

of interpretation by which we assimilate a work of art to our everyday

systems of explanation, and rob it of its peculiar felt force. When Emerson

wrote: "An imaginative book renders us much more service at first,

by stimulating us through its tropes, than afterward when we arrive at

the precise sense of the author," he was sketching the possibilities

of such a criticism. Kael, writing on the frayed edges of a great tradition

extending from Emerson to Stevens, is a kind of common man's advocate

for the uninterpretable experience of the sublime in art. Her effort is

precisely to locate in films the moments of energy, surprise, shock, or

tension more rudimentary and essential than any of the systems of history

and culture by which we normally understand them.

Kael subscribes to a snap,

crackle, and pop brand of criticism. A film is atomized into a succession

of instants and local excitements–the experience becomes a sequence of

primordial psychic zaps, pows, and whams. The point in to immerse yourself

in the sensory flow prior to thought, for the critic to become a conduit

of "uninterpreted," pre-cognitive experience. That is why Kael

takes characters" apart, anatomizing them into a collection of gestures,

glances, postures or even pieces of costuming anterior to psychology,

personality, and social relations. Let the opening paragraph of her review

of "Honeysuckle Rose" stand for all; the metaphors are almost

a literal exercise in anatomy:

In "Honeysuckle Rose"

Dyan Cannon is a curvy cartoon–a sex kitten become a full blown tigress.

Her hair is a great tawney mop, so teased and tangled that a comb

would have to declare war to get through it; her blouse is filled

to capacity, and her jeans are about to split. She has never looked

better.

To the extent that a performance

is constituted out of just such a collection of appearances, stances,

and looks, there is no more breathless describer of its mysterious energies.

Kael's astonishment at "Richard Pryor–Live in Concert" ("When

we watch this film, we can't account for Pryor's gift, and everything

he does seems to be for the first time") is typical of her delight

and wonder at the power of any performance–any such assembly of gestures,

postures, and stances by director, actor, or technician–to move her.

She is sometimes called an

"impressionistic" critic, but there is no writing further from

Hatch's chronicle of the adventures of a soul among the masterpieces.

The "impressions" Kael directs our attention toward are events

and details, however minute and fleeting, that are actually up there on

the screen, not Hatch's flight of free associations away from it. There

is no sharper eye for detail, and no eye quicker to test the details of

each particular performance against all previous film performances. What

Kael's highbrow critics miss when they call her allusions or metaphors

unscholarly or sloppy is that there is more relevant film history and

scholarship in three or four of her flashy references than in a dozen

film journal footnotes.

All of which goes to show why

in her chosen arena there is probably no critic now writing who can better

describe those moments in a film when there is more going on than can

be reduced to the systems of explanation on which most other critics rely

to get them safely through a film and a review. While other reviewers

are busy tidying up the experience of a film into neat metaphorical, psychological,

or sociological patterns–a prelude, invariably, to an argument in favor

of, or against, the streamlined experience which they've concocted–Kael's

prose echo-chamber of comparisons, allusions, and metaphors is engaged

instead in opening up new, free-floating possibilities of response and

reaction. A film becomes a succession of energetic dispersions, eccentricities,

and excitements that conventional thematic and metaphoric glosses only

gloss over.

Yet having acknowledged her

achievement, one still must admit the extraordinary blind spots in her

vision of film. If she exposes us to the unregimented, even irresponsible

energies of personal performances, it is at the expense of leaving out

an awful lot else. In fact, what seems left out of her meticulous anatomy

of gestures, glances, and looks, her aesthetic of frissions, shocks,

and visions, is simply all the rest of life. Kael's attention to the isolated

movements, shots, or postures that define a performance necessarily isolates

it from the social, political, and personal contexts that surround and

sustain it. Meaning drops away. Emotion (at least any emotion more complex

than an orgasmic thrill or chill) disappears–which is why Kael is ultimately

our greatest connoisseur of junk, trash, and flash–of junky movies, trashy

experiences, and the flashy effects in them. Everything that distinguishes

life from a roller coaster ride or a junk-food pig out disappears.

In the conclusion of "Against

Interpretation" Sontag called for an "erotics of art."

In Kael, her wish has been granted. Her criticism is an illustration of

what such a critical program might amount to. But the question is whether

any "erotics" is a sufficient conceptual framework for our experience

in or out of a movie theater. Surely, we also need a social psychology

of art, a politics of art, and a natural history of art. One reviewer

of Kael's most recent collection of essays aptly described her analyses

of the films she most admires as "all peaks and no valleys."

No one is her equal in pointing out "peaks" of interest and

excitement in our experience of a film, but isn't our emotional and intellectual

experience impoverished when we turn it into a series of peaks? Shouldn't

criticism (like film) provide a geography and geology of the rest of life

as well? In fact, don't the peaks matter only after we have established

the contexts that make them possible, traced their locations in relation

to the valleys and plains of the rest of experience sketched out the infrequency

of vision in relation to the rest of our lives and all our assertively

un-visionary moments? Kael is frequently praised as a great stylist, but

doesn't a great writing style have something to do with being deeply insightful

about the subject you are dealing with? For those who say this, it's as

if their appreciation of Kael's style is as detached from the actual meaning

(or lack of meaning) of her words, as her own appreciation of cinematic

style is detached from the meaning (or lack of meaning) of the films she

writes about. For it's an undeniable fact that, for more than thirty years,

with her taste for trash and flash, Kael has been wrong, wrong, wrong

about what films matter and what don't. In the end, it's not too much

to say that she ultimately reveals the fraudulence of Sontag's critical

stance. On the evidence of Kael's work, criticism without interpretation

reveals itself to be clinically brain-dead.

It would be hard to think of

a critical temperament more opposite to Pauline Kael's than Stanley Kauffman's.

While Kael trades on her capacities of conspicuous response, her enthusiasms

and excitements, Kauffman does the opposite. He seems at times almost

afraid to like a film. A poll of theatre owners a few years ago voted

him the second hardest critic in America to please–second only to John

Simon. Where Kael can be enthusiastic to the point of rhapsody and often

receptive past the point of silliness, Kauffmann is crusty, stodgy sternly

unimpressible, and doggedly negative about most films. Yet it is precisely

Kauffman's common-sensical stolidness that makes him most valuable as

a critic. He is absolutely unintimidated by trends, word of mouth, or

the cinematic preciousness, stylishness, and cleverness that carry the

day in so many other reviews.

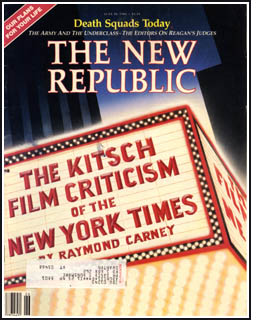

Kauffman (who reviews for The

New Republic, a journal of political opinion) represents a critical

sensibility so different from the artistic connoisseurship of Kael at

The New Yorker, that one is again forced to consider the issue

of institutional controls on individual discourse, controls that are only

more obvious in magazines like Time and Newsweek. If one

can imagine a moralist like Kauffmann–or Simon–writing for The

New Yorker, it is almost impossible to imagine The New Republic sanctioning

and encouraging Kael's cascade of impressions. So it is doubly instructive

to compare Kauffman's writing with that of another New Yorker critic,

Penelope Gilliatt, who until recently alternated reviewing duties with

Kael. Gilliat's writing is in many respects indistinguishable from Kael's,

and neither could be less like Kauffman's. Though the Three Mile Island

fiasco made "The China Syndrome" seem more important than it

would otherwise have been, both Gilliatt and Kauffmann wrote reviews of

it before it became a current events newsreel, and the differences are

revealing. For the first half of her piece, Gilliatt traces a pattern

of "hecticness" in the film, with an entertaining series of

apercus about particular scenes or moments within it:

Hecticness may be one of

the great banes of the Western world. Repose is rarely to be found....

Hecticness is one of the themes of James Bridges' "The China

Syndrome." The woman star, Jane Fonda, is Kimberly Wells, with

red-dyed hair that streams down her back, and looking ravaged by her

life as a "soft" TV commentator.... The film is rightly

cluttered with TV jargon and rush. No one has any time to pay heed

. . . we see to what trivial pressures her enacted ease is subjected.

Technicians and TV administrators are yelling commands about haste

at her all the time. Jane Fonda's performance is also about the non-stop

breeziness forced on our public commentators.

It is well to remember that

this is an aggressively political, even polemical film, because Gilliatt's

repetitions and variations on the theme of "hecticness," the

"non-stop breeziness" of her own analysis (like Kael's in so

many of her reviews), succeed in turning it into a sort of still life.

By extracting each of the events and scenes she notices from its political,

social, and dramatic background, she freezes them into a static pattern

of internal tensions. Each moment becomes somehow implicit in, or a repetition

of, another moment, and are all made to co-exist in the breathless present

of her review. But it is impossible even for this art-for-art's-sake writer

entirely to aestheticize "China Syndrome"–politics, society,

and the world outside the movie theatre are let in at the very end of

the review. But note the very special way they are brought into existence:

The head of the nuclear

power plant is a true bull-necked capitalist, only counting the billions

of dollars that would go down the drain if his plant were idle. Danger

be damned he thinks. "The China Syndrome" is a fine film

concerned with the harm being done to America by money-grubbing interests

that fail to look very far.

Is it accidental that it is

only another tableau-vivant? Who is this power-plant executive

anyway? A bit character actor in a Hollywood genre film. That "money-grubbing,

bull-necked capitalist" muttering "Danger be damned," while

"billions go down the drain," never lived in our world, not

for a minute. He's straight out of Metropolis or Modern Times.

We are back in a "scene" from a film, watching a "performance"

after all.

What makes Kauffmann interesting

is that even though his sensitivities overlap with Gilliatt's and Kael's

in some respects, he ultimately reacts against the aestheticism they (and

he) are susceptible to. The first two sentences of his review are revealing

and characteristic of his whole critical endeavor:

A smashing thriller–the

most exciting thriller I've seen since "Z." Grave questions

come along after it, but not until the excitement calms down, which

takes a while.

That second sentence, with

its retreat from the breathless enthrallment of the first, is a characteristic

gesture for this cautious, conservative, and self-scrutinizing critic.

But before Kauffmann takes

up his second thoughts, he gives full value to his initial excitement.

Jazz up his next few paragraphs with a few more metaphors and you might

be reading Kael on DePalma:

What's particularly good

about the picture's rhythm is that it doesn't follow the usual pattern

of suspense films: a fast start followed by a lull (you know, an opening

murder, then long passages of fill in), with alternating splotches

of action and drags of recovery until the final whoop-up. "Syndrome"

starts tight and keeps tight even before the material is particularly

tense. (The innate pressures of television broadcasting help it here.)

So as the material itself gets more hair-raising, the editing doesn't

seem to be accelerating. The whole picture is like a speeding train

on which events get more gripping as it speeds along.

The point Kauffmann is making

about the pace and rhythm of the film is, in fact, quite similar to what

Gilliatt called its "hecticness." But with the next sentence

Kauffmann turns his glance in a direction Gilliatt, Kael, Hatch, or another

critic of aesthetic thrills and pleasures never would:

But. After it's all over

and the pulse begins to subside–which takes time–the

worry comes.... The question here is villainy, not error....

If the film had only

underscored the constant possibility of human error in nuclear plants,

it would have done a service. But "Syndrome" also casts

its power executives as heavies in a James Bond flick.... Shortsightedness,

stupidity, and error are frightening enough possibilities in such

powerful men. But to show nuclear executives as so money mad

that

they knowingly risk explosion to make money, that they hire thugs

to help them–all this would take some proving in order

to clear the picture of the charge of irresponsibility.

The issue here is not whether

power company executives are really "bull-necked capitalists,"

or "short-sighted, stupid, and fallible." The issue is whether

one stays within the boundaries of the frame, and accepts the conventions

of a film at their own estimation, or holds oneself somewhere outside

the frame with Kauffmann, and requires that the film enter into dialogue

with recognizable and significant social, psychological, and political

forms outside itself. Kauffmann indeed beings by giving full value to

the melodramatic ingenuity and sensuous immediacy of the film before him.

This is the point to which Simon never gets, and the point at which Hatch,

Kael, and Gilliatt stop. But Kauffmann goes on–to test and measure the

experience in which he has been immersed; to express his reservations

about the way all melodrama simplifies, distorts, and falsifies; to express

doubts about how a particular film can presume to exonerate itself from

the fiction-mongering it pretends to be exposing in others. In his final

sentence he sums up his disturbing doubleness of vision: "Its very

effectiveness in sheer filmic terms makes it all the more worrisome."

The interest of all of his best criticism is Kauffman's unstable oscillation

between the "sheer filmic" forms and terms within a movie, and

his allegiance to the forms and terms of experience outside film.

Few critics more repeatedly

(and at times exasperatingly) resist the "filmic" in films in

order to raise literal questions about meaning, plot, and character. "Gorgeousness,"

"prettiness," "cleverness," and "artiness,"

far from being terms of appreciation in Kauffman's vocabulary, are his

ultimate condemnations. To say a film (a DePalma, or a Hitchcock) is a

stylistic tour de force is, for Kauffmann, to damn it once and for all

to the first circle of irresponsibility. If Kauffmann is often insufficiently

"cinematic" in his criticism, repeatedly moving outside the

frame of a scene to raise social or psychological questions, it is only

because he realizes that the forms of cinematic experience matter only

insofar as they communicate with the forms of extra-cinematic experience.

In a branch of criticism where stylistic brilliance or technical virtuosity

are so often celebrated as ends in themselves, he anxiously emphasizes

the responsibilities of style, and the irresponsibility of the merely

stylish. As his comments on "China Syndrome" suggest, Kauffmann

(like Denby) realizes that every style (however "brilliant,"

"clever," or "exciting") is at the same time a trap,

a limitation, a necessary betrayal or lie about experience especially

the eminently portable, disposable, and deployable styles of so many fashionable

cinematic tours de force.

Kauffman's greatest strength

is precisely his precarious balance between responsiveness to the sheer

cinematic forms on the screen and the forms of psychology and society

outside the theatre. His most severe limitation is that too often the

balance seems to tip toward the latter. At times he seems almost willfully

to resist the very energies of the medium to which he is supposedly devoted.

A deeper paradox of Kauffman's standards is that a too demanding criterion

of cinematic responsibility and "realism" can, oddly enough,

become another more subtle form of cinematic aestheticism. Realism is

after all only another style; and the quest for the well-made screen-play

and the well-acted role, like the Pre-Raphaelites' artistic quest for

innocence, can itself become an insidious kind of artsiness. Sometimes,

as Kauffmann is busily analyzing the minutest details of the lighting,

blocking, and acting of a particular scene, all supposedly in the interests

of arguing for or against its fidelity to life, it is possible to ask

whether well-made characters, plots, and dramas haven't become ends in

themselves, whether Kauffmann, the self-proclaimed enemy of cinematic

rhetoric and manipulation, isn't at these moments only the slave of the

form of rhetorical manipulation we call realism. If aestheticism is the

narrowing of one's range of response and appreciation, then certainly

Kauffman's repudiation of so many kinds of cinematic stylization and artfulness

becomes at times its own form of aestheticism.

Having said this, it must be

admitted that he brilliantly uses his realistic bias, his interest in

society and politics in films, to describe the social and political forces

that really produce the films we see. While other critics are spot-lighting

a particular star or director as if films really were made the way fan

magazines describe them, Kauffmann keeps reminding us of the much less

romantic realities of modern film production. Few critics are better at

tracing and teasing out the practical compromises that go into the final

product, the necessary conflicts and different contributions of the actors,

writers, directors, and technicians who make a film possible.

Kauffmann at times forces films

to shoulder inordinate burdens of responsibility and significance, but

there is no critic correspondingly harder on himself and his own writing.

He is a meticulously, even depressingly, careful writer at the furthest

remove from Kael's gush of excitement and exhortation, a critic laboring

under the burden of his own self-appointed responsibilities. To follow

his weekly pieces in The New Republic is to watch Kauffmann continuously

watching himself, measuring his passions, correcting, extending, reassessing,

weighing his own judgments as severely as he weighs the films he watches.

If he is overly impatient with

the frivolous, too testy about the slightest manifestation of artiness,

a little too anxious in his search for masterpieces, it is only because

he takes movies too seriously ever to allow them to become only occasions

of energy, entertainment, or escapism. For all his crusty, occasional

tartness of manner, his literal-mindedness about plots and characterizations,

his parochialism of response, there are very few critics with such an

exalted sense of the potential importance of film. While Kael and all

too many other critics read like people who live in order to go to the

movies, Kauffmann never allows up to forget that he goes to the movies

in order to live.

Whatever their other differences,

Kael and Kauffmann share an urgency (some would say a stridency) about

films to which it would be hard to imagine a greater contrast than the

chatty, playfully punning geniality of Andrew Sarris at the Village

Voice. If Kael is the enraptured chronicler of the visionary "eye"

temporarily liberated from the limitations of time, society, and personality,

Sarris is the humane celebrator of the sovereignty and power of the

thoroughly

personal "I." Sarris himself recently defined the difference

between his sensibility and Kael's by contrasting a scene he liked in

the cinematic soap opera, "Ordinary People," with Brian DePalma's

exercise in camp horror in "Dressed to Kill," which Kael had

praised extravagantly: "There is more genuine horror in [Mary

Tyler Moore's dropping her son's French toast down the garbage disposal,]

than

in all the bloodletting of 'Dressed to Kill.'"

His differences with Kael go

back a long way. They both made their reputations in the early 1960s by

a polemical spat over Sarris' application of the French politique des

auteurs to Hollywood studio films. There are significant practical

and theoretical problems with Sarris' position, and Kael masterfully pointed

some of them out to him in their debate, but their differences over auteurism

are really beside the point. What Kael (and most of Sarris's other critics)

failed to realize was that Sarris wasn't even remotely interested in auteurism

as a coherent and defensible intellectual position. Though, as a fairly

ambitious and inexperienced young reviewer, Sarris may have chosen to

wrap himself in the protective mantle of an esoteric, transatlantic intellectual

movement, the sheer ineptness of most of his replies to Kael's objections

showed his utter ignorance of, and indifference to, most of the theoretical

underpinnings of French auteurism. And his classic application of auteurism

to Hollywood movies in his first book, The American Cinema, devotes

hardly a page to the theory and philosophy behind the whole project. Auteurism

didn't come to Sarris from France, or as a result of meditations on the

aesthetics of film, it happened (as he explained in his introduction to

The American Cinema) as he walked up the aisle of a movie theatre:

" 'That was a good movie,' the critic observes. 'Who directed it?'

When the same answer is given again and again, a pattern of performance

emerges." Auteurism was Sarris's way to legitimize his love for a

group of studio directors–from Welles, Hitchcock, and Lubitsch, on down

to men like Preston Sturges, Don Siegel, and Douglas Sirk who were regarded

by other critics as studio hacks. What Sarris liked was nothing more complicated

than their abilities to make their personalities felt in a film. The "pattern

of performance" Sarris traces in the careers of 200 directors in

The American Cinema is simply Sarris's unsophisticated celebration

of the recognizability of the styles, the signatures, and the temperaments

of these directors.

Nothing fascinated Sarris more

then, or motivates more of his writing now, than this faith in the little

man making his way against alien styles. Alfred Hitchcock's icy wit, John

Ford's gruff sentimentality, Jimmy Stewart's "stone faced morbidity"

are all evidences of the power of personality to survive, even in the

slightest and most quirky manifestations, against the great artistic levelers

of our time–the homogenizing and impersonalizing pressures of the genre

film, the commercial market, and the studio production system.

It's not surprising, then,

that Sarris should be weakest on those films which most interested Kauffmann–films

that attempt to be more (or less) than personal documents, films that

aspire to significance, generality, and impersonality. In The American

Cinema Sarris even invented a special category (called "Strained

Seriousness") within which to gather (and dismiss) films that made

such attempts. Likewise, Kael and Sarris also are at odds over the issue,

Sarris being almost indifferent to the sort of cool transcendence of personality

in a performance that mesmerizes Kael. So fascinated is she by just the

sort of meticulous calculation and mastery of gesture that leaves personality

behind that she can actually criticize Bette Midler for "losing her

cool" at the end of a show and getting "personal." While

hardly anything leaves Sarris more bored and irritated than a stylistic

tour de force, a cinematic event that exempts itself from the continuous

adjustments and by-play of a thoroughly personal relationship, whether

of characters to each other, of actors to a script, or of a director toward

his actors. In fact no word has more harrowing connotations for Sarris

than Kael's favorite adjective of praise: for Sarris, Eisenstein is "cool,"

and Murnau fortunately is not; DePalma is "cool," and Cassavetes

fortunately is not; Kael is "cool" and he deliberately is not.

It's probably not coincidental

that Sarris's own position at the Village Voice has significant

parallels with that of the studio directors in whom he is most interested.

In a characteristically anecdotal review of "Hopscotch," he

compared his journalistic situation with that of the film's central character,

a man who asserts the power of his personality against the bureaucracy

of the CIA:

Kendig is a middle-aged

man demoted in his profession because he is too much of an individualist

to fit into an impersonal system. I can think of few middle-aged men

in America who can't identify with [him]. In my own case I started

working here at the Voice as a helper in a Mom-and-Pop shop, and I

am now a cog in a conglomerate.

But, of course, what an anecdotal

excursion like this proves, is that the one thing Sarris will never allow

himself to become is "a cog in a conglomerate." In an important

sense, Sarris, asserting the power of his individual voice in the Village

Voice, has always been fighting the same struggle as the filmmakers

he most admires, a struggle to assert the strength of his self against

all the person-leveling tendencies of an institution. In the final reckoning,

Sarris's promotion of auteurism, and his personalized approach to film

criticism are one–one song of praise and faith in the potency and importance

of the human personality.

Sarris's strengths are inseparable

from his weaknesses. His charming and chatty style, his anecdotally autobiographical

approach, and above all his thoroughly humane view of films, define both

the special sensitivities of his criticism and its ultimate shortcomings.

His writing, even about the films he most admires, is maddeningly weak

on close, detailed studies of particular scenes and events. Just when

one needs a careful description or discrimination, Sarris will ground

his review in the vague adjectives: a scene or a character is "warm,"

"sincere," "Iyrical," or "convincing." These

are words an under-graduate film major has already learned to avoid, and

one is reminded at a moment like this that Sarris for better or worse

is an autodidact who began with no formal education in film criticism.

But these adjectives also tell us something more important. They remind

us of a vital difference between Sarris and both Kael and Kauffmann–of

how unwilling Sarris is to dissect a film beyond ordinary units of felt

human emotion, and of how for him watching a film does all come down simply

to "sincere," "warm," or "Iyrical" moments

of human relationship.

Sarris's style and approach

to films is the warmest and most humane of the three critics I am discussing

here. But precisely in proportion to the affability, sincerity, and generosity

it possesses (and it possesses them abundantly), it raises the question

of whether personality and temperament (especially in an art as technologically,

bureaucratically, and commercially top-heavy as contemporary filmmaking)

can possibly be as sovereign and effective as Sarris wants and needs them

to be. The relations of film forms and film roles, of traditions and individual

talents, of genres and instances, seem altogether more mysterious, less

direct, and more difficult to trace than Sarris's cult of personality

and vocabulary of emotions can account for. One doesn't have to be a semiotician

to see that criticism needs to move beyond the romantic myth of the isolated

artist and the fallacy of the search for personal origins for works of

art. There are moments even in the most personal films–moments of wildness

or eccentricity as well as moments of conservatism or repression–that

can never be traced back to any personal relationship, and that transcend

any of the personal meanings and interpretations we may want to attach

to them. But that is only to say, for some things we must read Kael and

Kauffmann.

The point of course is not

to try to choose between Kael, Kauffmann, and Sarris. Each offers a radically

different focus on film and reminds us of the immensely different energies

that generate any work of art, and of the incompatibly different contexts

within which any work establishes itself. But it is especially appropriate

to end with Sarris if only because he reminds us of the fundamentally

unsystematic, untheoretical amateurism of each of these three major critics

and of the very best of their colleagues–David Ansen at Newsweek,

David Thomson at Film Comment, and David Denby at New

York Magazine. They regard film as a form of human communication, and their

own task more than anything else as simply to communicate some of the

richness of their film experiences to their readers. American film criticism

since James Agee is amateur criticism, and Kael, Kauffmann, and Sarris

are all amateurs in the best sense of the word. They are lovers of film,

passionate about their experiences owned, operated, and trained by no

school or movement, following the great tradition of amateur film criticism

bequeathed to them in this country by Otis Ferguson, James Agee, Robert

Warshow, and Manny Farber.

As Auden recognized, the role

of the popular film critic is almost unique in our culture. There is no

criticism of any other art now being written with a larger, more devoted,

more passionate readership. Writing on music and painting hasn't had this

kind of audience since the scandals of the early twentieth century. Literary

criticism lost its ties to a general community of writers and readers–the

sort of nonspecialized audience that follows Canby, Kael, or Kauffmann

on a regular basis–long before New Criticism came along with its technical

jargon and air of scientific explanation. The proliferation of specialized

journals and fields of study in our universities has only guaranteed that

most professional academic criticism has more and more become the private

property of the particular professions. These film critics inhabit a special

and quite privileged moment in history.

But this general community

of film critics and movie lovers is already dissolving, and the era of

these genuinely amateur critics is drawing to a close. As these journalist-critics

would be the first to admit, they are almost certainly the end of their

line. They are the last generation to feel the luxury of its absolute

amateurism, to be free completely to follow its interests and passions,

to be free to invent or discover its own methods, vocabularies, and styles

of writing about film. The professional film schools are already educating

and graduating their replacements. Critical methods courses and text books

are being organized. New journals are beginning to publish "scholarly,"

sanctioned film criticism in the best footnoted, PMLA tradition.

The prospect of what will be done by the next generation of film critics

writing as professionals with standardized methods for established institutions,

is daunting. It's an especially good moment, therefore, to be grateful

for what has been done by this generation, untrained, unspecialized, unsystematic,

and unencumbered with professional jargon or affiliations, writing in

the dark about the mystery and excitement of their experiences....

–Excerpted from "Writing

in the Dark: Film Criticism Today," The Chicago Review, Volume

34, Number 1 (Summer 1983), pages 89-116.

* * *

The Hazards of

Humanism

The corrupting influence of Vincent Canby and The New York Times

on American Criticism and Culture

You have to fight

sophistication. –John Cassavetes

One

of the dozen or so most powerful and influential men in the world of film

has never produced, written, directed, or acted in a movie. He doesn't

even live on the West Coast. Vincent Canby, the 61-year-old first-string

film critic for the New York Times for the past 16 years, lives

on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, and has no official connection with

the glitzy world of the studios. But he has the ability to make or break

the fortunes of scores of films every year. One

of the dozen or so most powerful and influential men in the world of film

has never produced, written, directed, or acted in a movie. He doesn't

even live on the West Coast. Vincent Canby, the 61-year-old first-string

film critic for the New York Times for the past 16 years, lives

on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, and has no official connection with

the glitzy world of the studios. But he has the ability to make or break

the fortunes of scores of films every year.

Confronted with such a description

of his critical clout, Canby vehemently denies it. First, he argues that

certain films are almost guaranteed to find bookings and make money no

matter what is said about them; the association of a particular star or

director with a project (say, Barbra Streisand, Clint Eastwood, or Steven

Spielberg) or the presence of certain trendy themes, combined with the

commitment of a major studio to a saturation advertising campaign, can

make a specific movie practically critic-proof. Still, these guaranteed

blockbusters are few and far between (as investors learn to their sorrow).

Indeed, as the exceptions, they only prove the rule of Canby's power in

the vast majority of other instances.

Second, Canby insists that

his power is not really personal at all. As he told one interviewer: "It

is only the power of the Times, because the Times

critic doesn't really exist outside of the Times." It's true

that Canby's influence is not something he achieved on his own; the infamous

Bowsley Crowther, Canby's predecessor, who wrote regularly for "the

newspaper of record" and reigned in undisputed glory from 1940 to

1968, had the same power as Canby does today. But it is a distinction

without a difference. However accrued, and however personally unearned,

Canby's power is power nevertheless–and it is as great as the power of

some of the biggest stars and producers in the business.

The distinctive power of the

Times reviewer results from a virtually unique confluence of geographical,

demographic, and bureaucratic factors peculiar to the relationship of

the Times and the film distribution system in this country. New

York City–not Washington, Boston, or Los Angeles–is the initial port

of entry for virtually every important, unconventional, or independently

financed American or foreign film. How such a film performs in the first

few days or weeks of its initial run in New York commonly determines not

only the size of the advertising budget that will be committed to it and

the number of bookings it will subsequently receive, but in many cases

whether it will ever receive any general distribution at all. If a film

that wasn't produced as a guaranteed blockbuster (that is to say, a film

that stands a chance of being interesting or innovative) fails to pack

them in during its initial run in New York, there is a real likelihood

that it will simply be pulled from distribution and written off as a tax

loss by its backers. Thus, the New York reviewer, who writes about films

released in and around the city and is read by residents of the city and

its immediately outlying areas, has an inordinate influence within the

film distribution system itself.

By this logic a reviewer at

the New York Post or Daily News would have clout equal to

Canby's, but the special distribution and readership of the Times make

it uniquely powerful when it comes to determining the destiny of certain

kinds of films. Its circulation is relatively small, as things are reckoned

in this era of mega-reader and -viewership (approximately one million

in the daily edition and a million and a half in the Sunday–though one

should multiply the Sunday circulation by at least two for the probable

readership for any given issue). But, as the ad agencies say, it is not

the numbers that count, but the demographics. The Times has a near-monopoly

on the attention of a certain kind of upscale reader. From Princeton to

New Haven, yuppie couples, middle-aged professionals and businessmen,

and tweedy Ivy League alums of all stripes define the typical Canby reader.

And this is exactly the audience–one with the financial wherewithal,

the leisure time, and the artistic curiosity and presumed independence

of aesthetic judgment–that determines the fate of the non-blockbuster

or innovative film. It is this audience that Canby either delivers or

doesn't.

Indeed, it might be argued

that three recent changes have made Canby's power even greater than Crowther's,

or any previous Times critic's. First, there has been the decline

of the studios as committed promoters of their own work; even B-pictures

were once part of a larger package of films assured of being given some

minimal level of promotion and support no matter how they fared in their

initial weeks. Second, the cable television market has expanded (which

encourages producers of small-budget or independent films to maximize

their short-term gains and minimize their projected long-term losses by

pulling a film from theatrical distribution and dumping it on the cable

market if it gets into critical or commercial trouble). Finally, the psychology

of the individual ticket purchaser has changed; where film-goers in the

1940s and 1950s simply went out "to see a picture" (often any

picture) on Saturday nights, the critically informed, college-educated

viewer in this era of higher ticket prices and less accessible theaters

increasingly looks to specific critics for advice on whether or not to

go to a particular film. All of which is why it is no exaggeration to

say that the fate of the non-blockbuster, non-critic-proof movie–the

small, independent, innovative, unusual film–hangs in the balance every

time Canby chooses to write about it, or not to.

I don't mean to slight the

reviewing of his junior colleagues who also write on film for the Times.

But it is undeniable that Canby is officially their supervisor (under

the general editorship of Walter Goodman), and that he sets the tone and

style for much of their work. Nor is it my intention to make the job of

a regular film reviewer sound easier than it is. The effect of sitting

through hundreds of absolutely dreadful films a year must be one of the

most mind-numbing and spirit-killing imaginable. The percentages are relentlessly

against the critic with high standards: 19 out of 20 films are guaranteed

to be an almost complete waste of time. Thus the temptation to become

cynical about the whole process, to lower one's standards in order to

salvage a bit of self-respect by finding redeeming qualities in whatever

piece of drivel one is forced to watch, is almost overwhelming. But it

is precisely the rarity of a work of true intelligence and beauty that

makes it all the more important that a critic not become cynically relativistic.

He must, instead, hold fast to his values in order to be able to distinguish

the rare good film when it does come along.

That is what Canby has failed

to do. He sold out his critical standards long ago in order to avoid the

hard words and stern judgments that otherwise would be required of him

over and over again. Instead, nothing is taken very seriously or objected

to very strenuously. The result is a critical abrogation of values. Canby

represents the clubman as critic.

Canby's critical beliefs and

practices are inseparable from the general tone he takes in his reviewing.

It is almost invariably light and disarmingly facetious. The effect, at

first, is one of extreme geniality; nothing seems to ruffle or upset Canby.

But what seems pleasantly facetious when applied to the latest installment

of Rocky or Star Wars eventually becomes annoying when applied

to almost everything. Of course, most Hollywood film is indeed junk food

for the senses, and deserves no better or more serious treatment. Still,

Canby doesn't quite take any of the serious films he views seriously

enough to become passionate or earnest about them.

Everything is a bit of a goof,

an occasion for urbanity, an experience of irony. It seems no accident

that the films he most likes tend to be blandly genial in the way his

writing usually is. To call a film "funny," lightly "entertaining,"

or above all, "not to take itself too seriously" is, for Canby,

one of the supreme forms of praise. To treat a work of art in a cute,

tongue-in-cheek way is a rhetorically expedient method for any critic

who would spare himself the effort of difficult critical discriminations,

and the potential dangers of a personal commitment to a serious judgment.

Canby's techniques of intellectual hedging or equivocation are many. He

is, first, a master of the lightly ironic use of the negative understatement

to suggest more than he is ever willing to commit himself to in a positive

way. This is what in classical rhetoric is called the use of "litotes"–saying

what something is not rather than what it is. At least as long ago as

Mark Antony's funeral oration for Julius Caesar, rhetoricians have known

that ironic negatives are always politically safer and argumentatively

easier than a clear commitment to anything positive. Canby's favorite

and most maddening way of deploying negative understatements is in pairs,

in a strategy of the excluded middle. Consider this: "Though it's

far from being an exercise in avant-garde techniques, Smithereens

is not especially conventional." Or this: "[The writer and the

director of Alligator] do not transform the formula film into some

higher art form, but neither do they rip it off." Or this, about

one of the James Bond films: "For Your Eyes Only is not the

best of the series by a long shot, but it's far from the worst."

You get the idea. Canby gets full credit for critical judiciousness, and

for a sense of historical or generic context, even as he archly and ironically

avoids the bother of having to stake his judgment on anything particular

at all. On occasion the pairing can even be between two positives, as

when we are told that Ed Pincus's Diaries "inevitably reveals

a lot more and a lot less than meets the eye," and the film itself

disappears completely.

But for Canby these are relatively

blatant equivocations. He is usually much more adept at fence-sitting.

One of his subtler techniques involves modifying a potentially positive

statement with a potentially negative one, with no indication of the discrepancy

between the terms. One might call it praising with faint damns, as when

he describes The Godfather as "a superb Hollywood movie,"

or characterizes Raiders of the Lost Ark in the following terms:

If Hollywood

insists on making films designed to gross hundreds of millions of dollars

by appealing to the largest possible audiences, it could not do much

better than this imaginative, breathless, very funny homage to the glorious

days of B-pictures.

It is crucial to take in the

double-edged quality of these modifiers, which, in case we don't get the

point, is explained in the final sentence of The Godfather review,

when Canby sums up the film as "one of the most brutal and moving

[signs of shilly-shallying already creep in with this doublet] chronicles

of American life ever designed [and watch this final twist] within the

limits of popular entertainment." Canby wants credit for asserting

something that he is not only unable or unwilling to defend, but that,

when challenged, he reserves the right to unsay.

His use of deliberately wacky

metaphors is another way in which he coyly and self-protectively distances

himself from his own comments, as when in his review of Syberberg's Our

Hitler he compares the director to a character in Animal House:

Like the dopey student in

National Lampoon's Animal House, who, as he smokes marijuana

for the first time, is suddenly aware of the universes contained within

the atoms of his own little finger, Mr. Syberberg is not one who quickly