What

critics and reviewers have said about

Ray Carney's The Films of John Cassavetes

|

Click

here for best printing of text

| The Boston

Globe “A

Cinematic Maverick” |

|

Over the past ten years,

in a torrent of essays, articles, and interviews, Ray Carney has

established himself as one of America's most brilliant and merciless

critics of the American film establishment in all of its crass commercialism—from

the producers and directors who package “star vehicles” to maximize

profitability, to the distributors and exhibitors who see to it

that the same ten titles play at every multiplex from coast to coast,

to the television, radio, and print journalists who all too often

function as mindless extensions of the studio ad campaigns. His

sharpest barbs, however, have been reserved for the academic critics

and university film programs that give Hollywood the sheen of intellectual

legitimacy by bringing its celebrities into the classroom and its

movies into the curriculum.

Of course, we've heard

much the same thing in the past decade from neo-conservative image-phobes

like Allan Bloom, William Bennett, and Hilton Kramer, all of whom

apparently equate the rise of the movies with the fall of Western

civilization. But what makes Carney's critique completely different

from theirs is that Carney, a professor of American studies and

film at Boston University, does not despise movies. His complaint,

in fact, is not that film reviewers, critics, and college teachers

take movies too seriously, but that they don't take them seriously

enough. In Carney's view, if they really cared about the art of

film, they wouldn't waste their time being trash collectors in the

ghetto of pop culture genre studies.

Yet being a nay-sayer

is too easy. The hard thing is to show how do it right, to say what

you would put in place of what you are criticizing. That is why

it is a special event, every few years or so, when Carney publishes

a book that illustrates what film study and analysis can be at their

most visionary and inspiring. Carney is clearly a born teacher,

and here as in his four previous film books his vast learning (which

takes in a wide range of American art and philosophy) and his obvious

love for his subject seem almost enough to win figures like Bloom,

Bennett, and Kramer to the cause of film study.

Every page of The

Films of John Cassavetes is informed by the passion of a man

on a mission to change the way movies are thought and written about.

Carney has an extraordinarily exalted view of the function of cinematic

art. Film is, for him, neither escapist entertainment and recreation

(as many journalistic reviewers regard it) nor an intricate stylistic

game played off to one side of life (as most film professors treat

it), but a way of exploring the most important and complex aspects

of the human experience. What he writes about Cassavetes' work here

summarizes his approach to all of the films he cares most deeply

about: “[Cassavetes'] films explore new human emotions, new conceptions

of personality, new possibilities of human relationship. He explores

new ways of being in the world, not merely new formal 'moves.' His

films are not walled off in an artistic never-never land of stylistic

inbreeding and cross-referencing. Cassavetes gives us films that

tell us about life and aspire to help us to live it.”

While most film scholars

are haggling over the date when deep focus photography was invented

or how many shots are employed in the shower sequence of Psycho,

Carney roves over the entire history of American film—from Griffith

and Capra, to Welles and Hitchcock, to Kubrick, Altman, and Allen—and

addresses ultimate questions of meaning and value. One of the most

exciting aspects of this book is the impression it conveys that

absolutely everything is open to reappraisal and revaluation. In

a series of extended analyses, Carney takes up many of the canonical

figures in American film history and offers stunningly new and controversial

reinterpretations of their work. Orson Welles's Citizen Kane

is criticized for its “rhetorical tendentiousness” and stylistic

flamboyance, and judged to be an example of “kitsch modernism.”

Hitchcock is taken to task for the “shallow mystifications,” emotional

manipulativeness, and denial of physicality in his films. Even Robert

Altman, currently the darling of many contemporary critics, is knocked

for the superciliousness, snideness, cynicism, and negativity of

his work.

Cassavetes, the no-budget,

maverick independent, is the book's heart and soul. In his characteristically

iconoclastic way, Carney argues that Cassavetes was the greatest

genius of recent cinema, and unapologetically positions his films

(which include Shadows, Faces, Husbands, Minnie

and Moskowitz, A Woman Under the Influence, The Killing

of a Chinese Bookie, Opening Night, and Love Streams)

alongside the work of many of the most important nineteenth- and

twentieth-century American writers, artists, musicians, and philosophers.

Not the least innovative aspect of Carney's writing is the degree

to which it is radically interdisciplinary, and he sketches a series

of strikingly original (yet persuasive) connections between Cassavetes'

work and that of other American artists and thinkers: Ralph Waldo

Emerson and Henry James, John Singer Sargent and Willem De Kooning,

William James and John Dewey, Louis Armstrong and Charlie Parker,

George Balanchine and Paul Taylor. Since Cassavetes' achievement

is still virtually ignored by academic film scholars, Carney is

undoubtedly aware of the apparent outrageousness of the claims and

connections he is urging. But I'm sure that is one of the reasons

he wrote the book. His goal has always been to overturn academic

apple-carts, to rock institutional boats, to gore intellectual sacred

cows.

The Films of John

Cassavetes echoes with the cadences of Emerson, one of Carney's

most resonant intellectual sounding boards. As I turned the pages,

almost holding my breath at moments, startled by the depth, power,

and unexpectedness of the argument, emotionally suspended between

exhilaration and fear, I found myself remembering one of my own

favorite Emerson quotes: “Beware when the great God lets loose a

thinker on this planet. Then all things are at risk.”

|

| The

San Francisco Review of Books

|

| “Any reader

of [The Films of John Cassavetes] will be driven to reassess

any notion they have ever held about the cinema.... Carney invites

us to be as emotionally open as Cassavetes' figures and snap out of

the Hollywood-induced trance of critical detachment in order to clear

the space between heart and mind.” |

| Newport

This Week

|

| “[The Films

of John Cassavetes] digs deeper into the soul of works by the

late John Cassavetes than anyone ever has, and it offers a challenging,

interdisciplinary approach to analyzing film form and text.... [The

Films of John Cassavetes] will, no doubt, also please the inquisitive

movie buff who seeks a well-rounded analysis of a provocative body

of work that has left an indelible mark on the American film scene.” |

| Carole

Zucker in Film Quarterly

|

| “Shortly after the

death of John Cassavetes in 1989, I organized a panel in his honor

at an upcoming Society for Cinema Studies conference. To my chagrin,

the call for papers elicited only three responses—one from noted

Cassavetes scholar Ray Carney. The incident is emblematic of the way

Cassavetes has been elided from the film studies canon, for reasons

that have as much to do with the nature of Cassavetes' films as with

the present constitution and leanings of the film studies community....

As an unrepentant auteurist, Carney asserts [in his book] that Cassavetes

“is not only one of the most important artists of the twentieth-century,

but that the originality of his work was what doomed it to critical

misunderstanding.” Carney views Cassavetes in adversarial relationship

to what he calls the “visionary/symbolic” film. By this he means

films which foster fixed, detached, intellectual ways of knowing....

The characters...have an essentially contemplative relationship and

existence....” |

| David

Sterritt in The Christian Science Monitor

|

| “Carney's

approach to Cassavetes is shaped by the depth and discipline of scholarly

analysis, and also by the out-and-out enthusiasm of a movie-lover

writing about some of his favorite pictures.” |

| The following

scholarly review of my Cambridge University Press critical study

of Cassavetes’ life and work indicates the academic marginalization

of his work that existed as recently as 1996. As far as the academy

was concerned, seven years after his death, Cassavetes was still

an almost unknown director: |

A book review by Wheeler

Winston Dixon, Professor of Film at the University of Nebraska,

Lincoln, published in The Journal of Film and Video,

vol. 48 (Spring/Summer 1996), pp. 88-94.

Carney, Ray. The

Films of John Cassavetes: Pragmatism, Modernism and the Movies (New

York and London: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

John Cassavetes’ work

as an actor in such films as The Dirty Dozen (1967), The

Fury (1978), and Rosemary’s Baby (1968)

is well known, along with his numerous appearances on television

series of the 1950s and ‘60s. What is less known is that

Cassavetes, from 1957 on, was far more interested in the work

he could accomplish as a director than as an actor.

It was as a director

that Cassavetes felt he accomplished his most important work;

as an actor, he would appear in almost anything that would

help him pay the bills to support his art, because the Hollywood

studios were unremittingly hostile to his directorial vision.

Ray Carney’s The Films of John Cassavetes: Pragmatism,

Modernism and the Movies is a long-overdue tribute to

this great artist, whose works have been generally neglected

by both the critics and the public. Meticulously researched

and superbly detailed and indexed, the book emerges as a deeply

personal and warmly engaging study of the filmmaker as an artist.

Before

his death in 1989, Cassavetes directed a series of memorable

films on shoestring budgets, starting with Shadows (shot in

1957 and released in 1958, then completely reshot and re-released

in 1989) and continuing on with Faces (shot in 1965; released

in 1968), Husbands (shot in 1969; released in 1970), Minnie

and

Moskowitz (1971), A Woman Under the Influence (shot in 1972;

released in 1974), The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (shot and

released in 1976, then recut and re-released in 1978 “in

a completely reedited” version [(Carney 314]), and Love

Streams (shot in 1983, released in 1984).

Carney argues that,

as a body of work, Cassavetes’ completely “independent” films

(as opposed to Too Late Blues, A Child is Waiting, and even Gloria [1980], to my mind the most interesting of his “studio

system” films) “participate in a previously unrecognized

form of pragmatic American modernism that, in its ebullient affirmation

of life, not only goes against the world-weariness and despair

of many twentieth-century works of art” but further, precisely

because of their unconventional structure and content, resist “the

assumptions and methods of most contemporary [film] criticism” (i)

which emphasizes formalist concerns over humanist ones.

The author cites the

directorial style of Welles, De Palma (who directed Cassavetes

in The Fury), Hitchcock, Capra, Coppola,

Griffith, and others as mechanisms of control and stylistic elegance,

as opposed to the “pseudocumentary” (77) approach

employed by Cassavetes, which used rough, hand-held camera work,

directly recorded sound, available or minimal lighting, and meditational

editing that lingered on the characters long after the tension

of a conventional “scene” was dissolved.

***

For this unconventional

approach, Cassavetes paid dearly. During the director’s

lifetime, his eight most personal films (Shadows, Faces, Husbands, Minnie

and Moskowitz, A Woman Under the Influence, Chinese

Bookie, Opening Night [shot in 1977, released

in 1978, then withdrawn and released in 1991], and Love

Streams) were ruthlessly marginalized by poor distribution

and phantom availability in 16mm or video formats. Even now, Husbands, Minnie

and Moskowitz, and Love Streams are unavailable

on videotape (28). None is available on laser disc.

This inadequate distribution

insured that the films would never reach the public at large;

confined to “art house” openings in major metropolitan

centers, Cassavetes’ films were never given the chance

to attain any kind of commercial success. But, then again,

given their problematic structure and subject matter, did Cassavetes

ever have a hope of reaching a general audience? As the director

himself observed, “All my life I’ve fought against

clarity – all those stupid definitive answers. . . .

I won’t call [my work] entertainment. It’s exploring.

It’s asking questions of people” (184). He realized

that certain

people would like a more conventional form [in cinema], much

like the gangster picture . . . they like it ‘canned.’ It’s

easy for them. They prefer that because they can catch onto

the meanings and keep ahead of the movie. But that’s

boring. I won’t make shorthand films. . . . I want to

shake [the audience] up and get them out of those quick, manufactured

truths (282).

***

This

responsive, humanly chaotic visual style is directly at odds

with conventional cinematic framing, giving the viewer

of Cassavetes’ films “unbalanced relationships,

mercurial movements, unformulated experiences slopping over

the edges of the frame, bubbling over the intellectual containers,

breaking the forms that deliver them to us” (91). Resolutely

noncommercial and anti-narrativistic in the best sense, Faces is nothing so much as a working out of Cassavetes’ view

of human fallibility as a visual as well as a situation/social

dilemma. the characters in Faces are grandiose and theatrical,

yet they are one with the audience, so ordinary and unexceptional

that we embrace them out of a common bond of shared experience.

***

In [Minnie and

Moskowitz], as in his other works, Cassavetes asks his

audience continually to revise their interpretation of both

the events and the characters they are watching on the screen

and, above all, never to become complacent viewers of the

human experience. According to Carney, this unwillingness

to rely upon cinematic convention sealed

Cassavetes’ commercial doom . . . the supreme challenge

of his work is directed at the viewer. [His audiences must]

keep tearing up each of the understandings that emerge in

the course of the film in order to remain fresh. Like the

characters, we must open ourselves to a state of not-knowing

(138).

Carney argues that

this open-endedness,

this lack of solid ground, is a fact of existence of the human

experience. Yet nearly a century of cinematic practice has

trained us to accept only the knowable, to follow a certain

trajectory, to have faith in certain patterns of narration,

to believe that events will move to a certain, predictable

closure. This reliance on the moment, this willingness to embrace

the inexpressible, to allow for the constant shifts in tone

that make up, as Cassavetes puts it, the “life . . .

[of] men and women” (139), also alienates a good number

of professional critics in their responses to his work. If

a situation can’t be trusted, then who’s to say

that any resolution of a scene is more reliable than any other?

That’s just

Carney's point here – there is no solid ground,

there is no ultimate authority. Life continually moves

away from its mooring, seeks new paths, refuses to do what

we expect (and/or desire) of it. Only in the movies can we

escape to a predictable narrative “logic.” Nor

does Cassavetes’ visual style call attention to itself

in an attempt to concretize and stabilize the narratives he

allows to unfold. As the author states:

According to Carney,

most avant-garde

films don’t arouse the degree of resistance from a viewer

or a critic that Cassavetes’ work does because they implicitly

marginalize their own insights. They stylistically contain

the dangers dramatized; they do not release them into life.

Their assaults are formal, their fragmentations are stylistic,

their disorientations are intellectual. Cassavetes moves avant-garde

imaginative disruptions off of the screen and into the world

(134).

Carney demonstrates

that for Cassavetes, it is not the practice of distanciational

cinematic technical devices that is the hallmark of his work – it

is his embrace of the erupting and unexpected narrative shifts

of existence, told in a self-effacing, nonpyrotechnical style,

that holds the viewer.

***

Carney compares The

Killing of a Chinese Bookie with Citizen Kane,

but points out a critical difference between the two films

and the aesthetic premises of the two directors:

Unlike Orson Welles’s Citizen

Kane, The Killing of a Chinese Bookie criticizes

PR forms of human relationship without collapsing into

PR forms of presentation. . . . It shows the fatuousness

of Cosmo’s quest for contentless stylishness, charm,

and elegance without itself playing the same game in its

visual and acoustic effects. . . . Welles’s work

is organized around a contradiction. He was guilty of the

very thing he indicts in his protagonist. He was in love

with stylistic razzle-dazzle. He was captive to rhetorical

flourish and grandiosity. [Cassavetes] in contrast gives

us an art devoid of gorgeousness and forms of acting that

reject melodramatic enlargements. . . . He creates an art

that repudiates stylistic virtuosity and special effects.” (230-31).

The result is a film

that is dark, murky, and altogether harrowing, a view of life

as a series of lies, manipulation, frauds, and tawdry spectacles.

At 135 minutes in its first version (1976), and even at a reduced

108 minutes in Cassavetes’ 1978 recut, the world of Chinese

Bookie is one of unrelenting nightmare, the embrace of

tinsel and flash as the emptiness that lies behind the creation

of packaged performance, Cosmo’s world is unendurable,

except that by documenting it, Cassavetes has forced us to

witness that which is simultaneously fascinating and appalling – the

death of humanism created for mass consumption.

***

As Carney demonstrates,

Cassavetes showed us the multivalent possibilities of existence

as we are forced to live them on a daily basis, without resorting

to tricky camera moves or self-conscious editing, without following

predictable narrative scenarios, instinctively eschewing the

easy way out. Cassavetes’ work exists beyond the boundaries

imposed by conventional narrative cinema – it even exists

beyond the supposed freedom of the avant-garde.

At its best, Cassavetes’ cinema

is raw, unvarnished, and deeply positive. If we can just see

things pragmatically (as the title of Ray Carney’s book

suggests), then perhaps we can live without delusion. Cassavetes’ deeply

undervalued films are the personal testament of a director

who paid for his art with his body (as an actor) and who

compromised his artistic integrity. He emerges in The Films of John

Cassavetes: Pragmatism, Modernism and the Movies as one

of the most important and essential American directors the

cinema has given us; certainly the films he directed constitute

a cultural legacy of which any creative artist would justifiably

be proud.

© Wheeler Winston

Dixon and The Journal of Film and Video. Copyright

1996. All rights reserved by the copyright holders.

|

* * *

What

young filmmakers and students have said about Ray Carney's The Films

of John Cassavetes

| “This

book changed my life. It wasn't a pretty experience, either. I argued

with it. I dismissed it. I fought it tooth and nail. But in the end,

reading this book and seeing the films it discusses represented the

single most important educational, emotional, and artistic experience

I've ever had. I tell you, the thing is a mental a-bomb. I broke down.

It literally caused me a crisis of the faith regarding everything

that I thought I knew or held dear about filmmaking, and maybe even

the world. I lost friends. Not only does this book chronicle in deep,

loving detail the films, working methods, and world-view of one of

the most important (yet underappreciated) filmmakers in American cinematic

history, it is a manifesto, articulating and illustrating an entirely

original and brain re-wiring theory of flimmaking, present in the

films of John Cassavetes; a theory at odds with 99% of the films EVER

MADE. Everything you though you knew is suspect in the glaring light

of Ray Carney's prose. Forget Citizen Kane. Forget Casablanca.

Forget Vertigo. They're like fingerpaintings next to a Picasso.

Neither lightweight nor academically verbose for its own sake, Carney's

tone is as friendly as if he were chatting with you over a beer, yet

what he says is nothing short of revolutionary. It was simple: I was

blown away. Finding precedent for Cassavetes' work in the long-standing

American Romantic tradition of Walt Whitman, Emerson, William James,

John Dewey and others, Carney's book gives film its proper due as

the greatest 20th century artform. An artform, it suggests, still

in its infancy. What Cassavetes' films did to me was simple and profound

— they showed me a new way to experience the world. A new attitude.

A new awareness. Carney did the same thing, articulating those ways,

and celebrating them with the reader. I read a lot of film books,

but this is the beat-up, dog-eared one I go back to time and time

again. No plain-Jane film text is as insightful or inspirational.

Read it and you will never be the same again. I wasn't.” |

|

—Matthew

Langdon (Mlw8330@aol.com)

|

| "I'd like to corroborate

Matthew Langdon's review (above this one). I had the advantage of

having Ray Carney as a professor at Boston University. By some stroke

of genius (probably by administrative accident), all entering film

students were required to take a survey course from him on film art

before taking anything else. Carney started with warhorses like Hitchcock's

"Psycho" and made the roomful of us (vocally) do exercises

during the screening that exposed the highly polished but rather ridiculously

superficial artifice of the "classic film". We all thought

he was crazy. Here was this man -- that one friend described as a

combination of Andy Warhol and Orville Reddenbacher -- unsubtly undermining

a number of the most globally revered films! He then paraded a host

of highly experimental films (many from the library of Congress that

practically noone outside of a Carney class has ever or will ever

see) before us that were appallingly difficult and often downright

confrontational. It's pretty safe to say that practically none of

us really "got it" until long after that semester, possibly

years. At some point I did. Carney loves film just like we all do,

however he had recognized something that we (and, most likely, you,

too) had not, that film can be so much more than anything we had imagined

(or yet been exposed to). That's largely what he wanted to show us

in this class. Film is still a nascent art, highly immature in scope

and depth. So far, Cassavetes -- one of the EASIER filmmakers Carney

introduced us to -- is one of the handful of film artists that has

done something deeply new with the form since its inception. If you

develop an interest in Cassavetes, you will find this book essential,

and you will return to it after every screening." |

|

—Martin

Doudoroff

|

| “I have

been involved in cinema for nearly 15 years. In that time I have not

placed much value in the books that have proclaimed to have such a

strong knowledge on film theory and criticism. But there is one book

that stands out for me. This book not only delves into the mind of

one of America's most brilliant filmmaker's in the last 30 years,

but also offers invaluable insight into the birth of the true independent

cinema. Raymond Carney is considered the foremost authority on Cassavetes,

and this work clearly shows his prowess in this area. Carney delves

deep into the language and imagery of this great filmmaker, showing

how his characters were constantly at the center—and not the emphasis

on great camera set-ups, or brilliant lighting. Carney gives us the

critical analysis that is so vitally needed. A great relief from the

candy-coated Pauline Kaels, Vincent Canbys, and Roger Eberts who tend

to get all the press in this area. I would highly recommend this book

to anyone who is serious about independent filmmaking.” |

|

—Christopher

Brown (cbrown@designmedia.com)

|

| “A vital

and inescapable work of film criticism. One of the best books I've

ever read about anything. A deeply resonant investigation into the

life's work of American Cinema's greatest explorer. The book faces

every major convention in film studies and with the deft precision

of its argument turns each of them on its head; it challenges the

reader to discover for themselves what film is ultimately capable

of as an examination of our lives. Heretical, unorthodox, and superbly

written. Carney is the strongest and the most imaginative film critic

in the English language.” |

|

—Christopher

Chase (chasecj@yahoo.com)

|

| “The

Films of John Cassavetes: Pragmatism, Modernism and the Movies by

Ray Carney has fundamentally changed my relationship to art. The

book

begins with the most eloquent and precise shredding of current Hollywood

filmmaking and then proceeds to give incredible insights into Cassavetes'

filmmaking methods. Each sentence paves new inroads to understanding

Cassavetes as one of the great artists of the twentieth century.

I

have learned more about acting, editing, and writing from Carney's

brilliant analysis of Cassavetes' most important films than from

any

other book (filmmaking books included). This book is absolutely essential

to anyone who is struggling with expressing our inner turmoil—as

with all watershed works it teaches you about life much more than

just the apparent topic of Cassavetes' films.” |

|

—Lucas

Sabean (lsabean@bu.edu)

|

| “Carney

offers an utterly convincing critical analysis of the great artist's

work. The author compares Cassavetes to Ralph Waldo Emerson and John

Dewey in consciousness-shifting ways useful to anyone interested in

media, culture, philosophy, and art. Now, Carney, the leading Cassavetes

expert, MUST (I hope) offer the definitive biography of this great

artist: clearly one of the most original, courageous, and mature American

filmmakers. See Cassavetes' work on video (A Woman Under the Influence

and Love Streams are absolutely wonderful; shockingly good),

and then read this book. I heartily endorse it and sincerely hope

for that definitive biography. Viva Cassavetes (and Carney)!”

|

|

—scott693@hotmail.com

from Los Angeles, June 9, 1999

|

* * *

And,

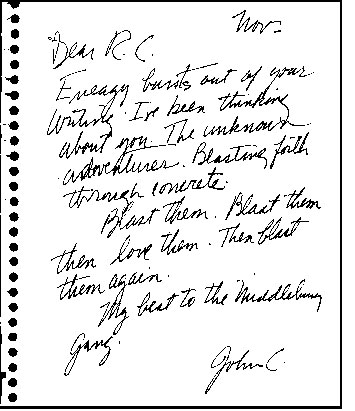

for a role-reversal, John Cassavetes on Ray Carney

(in a letter to him)

| “Energy bursts

out of your writing. I've been thinking about you. The unknown adventurer.

Blasting forth through concrete. Blast them. Then love them. Then

blast them again.... ” |

* * *

John

Cassavetes: Autoportraits

| On Ray Carney's

Autoportraits (Cahiers du Cinema) |

| “A beautiful coffee-table

sized book of b&w and color photographs of the Cassavetes' friends

and family. Also an introduction by Ray Carney. Photos by Sam and

Larry Shaw, and beautiful they are too. An expensive but essential

book. Literally do anything to own this book.....” (quoted from:

The Unofficial John Cassavetes Page ) |

* * *

Ray Carney, The Films of

John Cassavetes: Pragmatism, Modernism, and the Movies

(New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 48 illustrations,

paperback, 322 pages. This

book is available directly from the author for $20.

The Films of John Cassavetes tells the inside story of the making

of six of Cassavetes' most important works: Shadows, Faces,

Minnie and Moskowitz, A Woman under the Influence, The

Killing of a Chinese Bookie, and Love Streams.

With the help of almost fifty

previously unpublished photographs from the private collections of Sam

Shaw and Larry Shaw, and excerpts from interviews with the filmmaker and

many of his closest friends, the reader is taken behind the scenes to

watch the maverick independent at work: writing his scripts, rehearsing

his actors, blocking their movements, shooting his scenes, and editing

them. Through words and pictures, Cassavetes is shown to have been a deeply

thoughtful and self-aware artist and a profound commentator.

This iconoclastic, interdisciplinary

study challenges many accepted notions in film history and aesthetics.

Ray Carney argues that Cassavetes' films participate in a previously unrecognized

form of pragmatic American modernism that, in its ebullient affirmation

of life, not only goes against the world-weariness and despair of many

twentieth-century works of art, but also places his works at odds with

the assumptions and methods of most contemporary film criticism. Ray Carney argues that Cassavetes' films participate in a previously unrecognized

form of pragmatic American modernism that, in its ebullient affirmation

of life, not only goes against the world-weariness and despair of many

twentieth-century works of art, but also places his works at odds with

the assumptions and methods of most contemporary film criticism.

Cassavetes' films are provocatively

linked to the philosophical writing of Ralph Waldo Emerson, William James,

and John Dewy, both as an illustration of the artistic consequences of

a pragmatic aesthetic and as an example of the challenges and rewards

of a life lived pragmatically. Cassavetes' work is shown to reveal stimulating

new ways of knowing, feeling, and being in the world.

This book is available through

Amazon,

Barnes

and Noble, your local bookseller, or, for a limited time, directly

from the author for $20 (in discounted, specially autographed editions).

See below for information how

to order this book directly from the author by money order, check, or

credit card.

Clicking on the above links

will open a new window in your browser. You may return to this page by

closing that window or by clicking on the window for this page again.

* * *

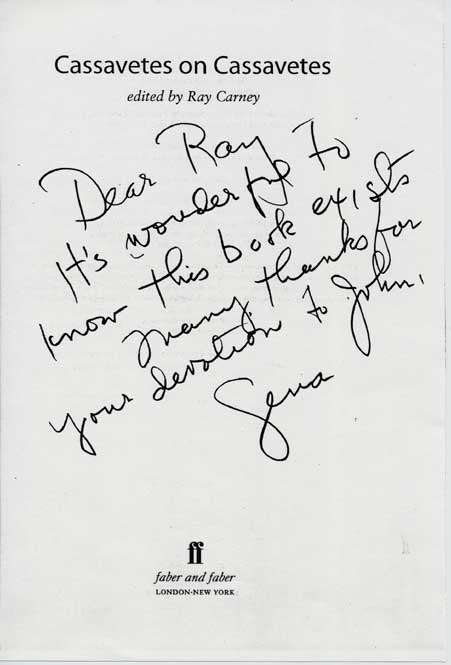

Ray

Carney, Cassavetes on Cassavetes (Faber and Faber in London,

and Farrar, Straus and Giroux in New York), copiously illustrated, paperback,

approximately 550 pages. Available directly from the author for $25.

Cassavetes

on Cassavetes is the autobiography John Cassavetes never lived to

write. It tells an extraordinary saga—thirty years of film history,

chronicling the rise of the American independent movement—as it

was lived by one of its pioneers and one of the most important artists

in the history of the medium. The struggles, the triumphs, the crazy

dreams and frustrations are all here, told in Cassavetes' own words.

Cassavetes on Cassavetes tells the day-by-day story of the making

of some of the greatest and most original works of American film. —from

the “Introduction: John Cassavetes in His Own Words” Cassavetes

on Cassavetes is the autobiography John Cassavetes never lived to

write. It tells an extraordinary saga—thirty years of film history,

chronicling the rise of the American independent movement—as it

was lived by one of its pioneers and one of the most important artists

in the history of the medium. The struggles, the triumphs, the crazy

dreams and frustrations are all here, told in Cassavetes' own words.

Cassavetes on Cassavetes tells the day-by-day story of the making

of some of the greatest and most original works of American film. —from

the “Introduction: John Cassavetes in His Own Words”

Click here to access a detailed description of the book and a summary

of the topics covered in it.

* * *

Cassavetes

on Cassavetes is available in the United States through Amazon

and Barnes

and Noble, and in England through Amazon

(UK), Faber

and Faber (UK). It is also available at your local bookseller, or,

for a limited time, directly from the author (in discounted, specially

autographed editions) for $25 via this web site. See

below for information how to order this book directly from this web

site by money order, check, or credit card (using PayPal).

* * *

Ray Carney,

John Cassavetes: The Adventure of Insecurity

(Boston: Company C Publishing, 1999), 25 illustrations, paperback, 68

pages. This book is available directly from the author

for $15.

|

- New essays on all

of the major films, including Shadows, Faces,

Husbands, Minnie and Moskowitz, A Woman Under

the Influence, The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, Opening

Night, and Love Streams

- New, previously

unknown information about Cassavetes' life and working methods

- A new, previously

unpublished interview with Ray Carney about Cassavetes the person

- Statements about

life and art by Cassavetes

- Handsomely illustrated

with more than two dozen behind-the-scenes photographs

Click

here to access a detailed description of the book. |

This book is

available through Amazon,

Barnes

and Noble, your local bookseller, or, for a limited time, directly

from the author for $15 (in discounted, specially autographed

editions). See below

for information how to order this book directly from the author by money

order, check, or credit card. This book is

available through Amazon,

Barnes

and Noble, your local bookseller, or, for a limited time, directly

from the author for $15 (in discounted, specially autographed

editions). See below

for information how to order this book directly from the author by money

order, check, or credit card.

Clicking on

the above links will open a new window in your browser. You may return

to this page by closing that window or by clicking on the window for

this page again.

* * *

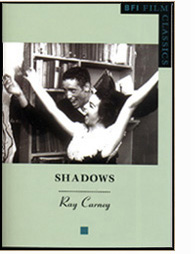

Ray Carney,

Shadows (BFI Film Classics, ISBN: 0-85170-835-8), 88

pages. Available in the United States in August 2001. This book

is available directly from the author via this web site for $20.

“Ray

Carney is a tireless researcher who probably knows more about the

shooting of Shadows than any other living being, including

Cassavetes when he was alive, since Carney, after all, has the added

input of ten or more of the film’s participants who remember

their own unique versions of the reality we all shared.”—Maurice

McEndree, producer and editor of Shadows

“Bravo!

Cassavetes is fortunate to have such a diligent champion. I am absolutely

dumbfounded by the depth of your research into this film.... Your

appendix...is a definitive piece of scholarly detective work.... The

Robert Aurthur revelation is another bombshell and only leaves me

wanting to know more.... The book movingly captures the excitement

and dynamic Cassavetes discovered in filmmaking; and the perseverance

and struggle of getting it up there on the screen.”—Tom

Charity, Film Editor, Time Out magazine

John Cassavetes’ Shadows is

generally regarded as the start of the independent feature movement

in America. Made for $40,000 with a nonprofessional cast and crew

and borrowed equipment, the film caused a sensation on its London

release in 1960.

The film traces the lives

of three siblings in an African-American family: Hugh, a struggling

jazz singer, attempting to obtain a job and hold onto his dignity;

Ben, a Beat drifter who goes from one fight and girlfriend to another;

and Lelia, who has a brief love affair with a white boy who turns

on her when he discovers her race. In a delicate, semi-comic drama

of self-discovery, the main characters are forced to explore who

they are and what really matters in their lives.

Shadows ends with the

title card "The film you have just seen was an improvisation," and

for decades was hailed as a masterpiece of spontaneity, but shortly

before Cassavetes’ death, he confessed to Ray Carney something

he had never before revealed – that much of the film was scripted.

He told him that it was shot twice and that the scenes in the second

version were written by him and Robert Alan Aurthur, a professional

Hollywood screenwriter. For Carney, it was Cassavetes‘ Rosebud.

He spent ten years tracking down the surviving members of the cast and

crew, and piecing together the true story of the making of the film.

Carney takes the reader behind

the scenes to follow every step in the making of the movie – chronicling

the hopes and dreams, the struggles and frustrations,

and the ultimate triumph of the collaboration that resulted in one of

the seminal masterworks of American independent filmmaking.

Highlights of

the presentation are more than 30 illustrations (including the only

existing photographs of the dramatic workshop Cassavetes ran in the

late fifties and of the stage on which much of Shadows was shot,

and a still showing a scene from the "lost" first version of the film);

and statements by many of the film's actors and crew members detailing

previously unknown events during its creation.

One of the most interesting and original aspects of the book is a nine-page Appendix that "reconstructs" much of the lost first version of the film for the

first time. The Appendix points out more than 100 previously unrecognized

differences between the 1957 and 1959 shoots, all of which are identified

in detail both by the scene and the time at which they occur in the

current print of the movie (so that they may be easily located on videotape

or DVD by anyone viewing the film).

By comparing

the two versions, the Appendix allows the reader to eavesdrop on Cassavetes'

process of revision and watch his mind at work as he re-thought, re-shot,

re-edited his movie. None of this information, which Carney spent more

than five years compiling, has ever appeared in print before (and, as

the presentation reveals, the few studies that have attempted to deal

with this issue prior to this are proved to have been completely mistaken

in their assumptions). The comparison of the versions and the treatment

of Cassavetes' revisionary process is definitive and final, for all

time.

This book is available through University

of California Press at Berkeley, Amazon, Barnes

and Noble, and in England through Amazon (UK)

and The

British Film Institute. For a limited time, the Shadows book

is also available directly from the author (in discounted, specially

autographed editions) via this web site. See

information below on how to order this book directly from the author

by money order, check, or credit card (PayPal).

Clicking on the above links

will open a new window in your browser. You may return to this page

by closing that window or by clicking on the window for this page

again.

For reviews and critical

responses to Ray Carney's book on the making of Shadows, please click

here.

Ray Carney, American

Dreaming: The Films of John Cassavetes and the American Experience (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985). $20.

[From the original dust

jacket description:] John Cassavetes is known to millions of filmgoers

as an actor who has appeared in Rosemary’s Baby, The

Dirty Dozen, Whose Life Is It, Anyway?, Tempest,

and many other Hollywood movies. But what is less known is that Cassavetes

acts in these films chiefly in order to finance his own unique independent

productions. Over the past 25 years, working almost entirely outside

the Hollywood establishment, Cassavetes has written, directed, and

produced ten extraordinary films. They range from romantic comedies

like Shadows and Minnie and Moskowitz to powerful,

poignant domestic dramas like Faces and A Woman Under

the Influence to unclassifiable emotional extravaganzas like Husbands, The  Killing

of a Chinese Bookie, and Gloria. Killing

of a Chinese Bookie, and Gloria.

This is the first book-length

study ever devoted to this controversial and iconoclastic filmmaker.

It is the argument of American Dreaming that Cassavetes

has single-handedly produced the most stunningly original and important

body of work in contemporary film. Raymond Carney examines Cassavetes’ life

and work in detail, traces his break with Hollywood, and analyzes

the cultural and bureaucratic forces that drove him to embark on

his maverick career. Cassavetes work is considered in the context

of other twentieth-century forms of traditional and avant-garde

expression and is provocatively contrasted with the better-known

work of other American and European filmmakers.

The portrait of John Cassavetes

that emerges in these pages is of an inspiringly idealistic American

dreamer attempting to beat the system and keep alive his dream of

personal freedom and individual expression – just as the characters

in the films excitingly try to keep alive their middle-class

dreams of love, freedom, and self-expression in the hostile emotional and familial environments in which they function. His films

are chronicles of the yearnings, desires, and frustrations of the

American dream. He is America’s truest historian of the inevitable conflict between the ideals and the realities of the American experience.

"By

far the most thorough, ambitious, and far-reaching criticism of Cassavetes'

work has been accomplished by Raymond Carney, currently Professor of

Film and American Studies at Boston University. Carney wrote the first

book-length study of  Cassavetes, who languished in critical obscurity

until the publication of Carney's American Dreaming in 1985....

In Carney's view, to settle the accounts of our lives, to decide once

and for all, is, for Cassavetes, to tumble headlong into the abyss

of nonentity upon which we incessantly verge. Carney argues that Cassavetes

has re-invented the craft of filmmaking in ways that drastically alter

our casual habits of film viewing. To adapt William James' terminology

(which Carney is indebted to) Cassavetes' works are concerned less

with the events and finished episodes that make up the 'substantive' parts

of our experience and more with the moments of insecurity, the 'transitive' slippages

during which our habitual strategies for understanding and stabilizing

our relationships with ourselves and others cease to function in any

useful way.... Carney's work with Cassavetes, placed within the context

of his later book, American Vision, on Frank Capra, can be viewed as

an attempt not only to further the understanding of American film,

but to forge a new synthesis of understanding in American Studies,

making his critical works valuable not only to film scholars, but to

students of American culture generally." — Lucio

Benedetto, PostScript Magazine Cassavetes, who languished in critical obscurity

until the publication of Carney's American Dreaming in 1985....

In Carney's view, to settle the accounts of our lives, to decide once

and for all, is, for Cassavetes, to tumble headlong into the abyss

of nonentity upon which we incessantly verge. Carney argues that Cassavetes

has re-invented the craft of filmmaking in ways that drastically alter

our casual habits of film viewing. To adapt William James' terminology

(which Carney is indebted to) Cassavetes' works are concerned less

with the events and finished episodes that make up the 'substantive' parts

of our experience and more with the moments of insecurity, the 'transitive' slippages

during which our habitual strategies for understanding and stabilizing

our relationships with ourselves and others cease to function in any

useful way.... Carney's work with Cassavetes, placed within the context

of his later book, American Vision, on Frank Capra, can be viewed as

an attempt not only to further the understanding of American film,

but to forge a new synthesis of understanding in American Studies,

making his critical works valuable not only to film scholars, but to

students of American culture generally." — Lucio

Benedetto, PostScript Magazine

American

Dreaming: The Films of John Cassavetes and the American Experience (Berkeley,

California: University of California Press, 1985), the first

book ever written about Cassavetes' life and work, in any language.

It has long been out of print but is now newly available through

this web site for $20 in a Xerox of the original edition. You

may order with a credit card through PayPal or through the mail

with a money order. See below.

***

In addition,

two packets of Ray Carney's uncollected essays on John Cassavetes

(material

not included in any of the above books) is also specially available

through this web site. The packet contains the texts of many of

his

notes and essays about the filmmaker. Available for $15.00.

Collected

Essays on the Life and Work of John Cassavetes (a packet of essays

by Ray Carney previously published in magazines, newspapers, and periodicals

and now unavailable). Approximately 130 pages.

A

loose-leaf bound packet of Ray Carney's writings on John Cassavetes

is specially available only through this web site. The packet has

the complete texts of program notes and essays about Cassavetes that

were published by Ray Carney in a variety of film journals and general

interest periodicals between 1989 and the present. It contains more than fifteen separate

pieces – including the keynote essay commissioned

by the Sundance Film Festival for their retrospective of Cassavetes'

work at the time of his death as well as the memorial piece on Cassavetes

awarded a prize by The Kenyon Review as "one of the best essays

of the year by a younger author."

This packet

also contains the text Ray Carney contributed to the "Special

John Cassavetes Issue" of PostScript edited by Ray

Carney, including "A Polemical Introduction: The Road Not Taken," "Seven

Program Notes from the American Tour of the Complete Films: Faces, Minnie

and Moskowitz, Woman Under the Influence, The Killing

of a Chinese Bookie, and Love Streams."

The Collected Essays

on the Life and Work of John Cassavetes is not for sale in

any store, and available exclusively on this web site for $15.00

under the same credit payment terms or at the same mailing address

as the other offers.

***

"Special

Issue: John Cassavetes." PostScript: Essays in Film and

the Humanities Vol. 11 Number 2 (Winter 1992). Guest editor:

Ray Carney $10.

Handsomely illustrated.

113 double-column pages (50,000 words).

A memorial tribute to the

life and work of John Cassavetes. Essays by Ray Carney, George Kouvaros,

Janice Zwierzynski, and Carole Zucker. Interviews with Al Ruban and

Seymour Cassel by Maria Viera. A history of the critical appreciation

of Cassavetes' work and a bibliography of writing in English by Lucio

Benedetto. The issue is illustrated with more than 40 behind-the-scenes

photos of Cassavetes and his actors and contains many personal statements

by him about his life and work.

This issue includes eight

essays by Ray Carney about Cassavetes' life and work: "A Polemical

Introduction: The Road Not Taken," and "Seven Program Notes

from the American Tour of the Complete Films, about Faces, Minnie

and Moskowitz, Woman Under the Influence, The Killing

of a Chinese Bookie, and Love Streams." But note

that Ray Carney's contributions to the special Cassavetes issue of PostScript magazine

are also available as part of the packet, The Collected Essays

on the Life and Work of John Cassavetes, which contains many

other pieces by Prof. Carney as well. The Collected Essays packet is listed separately above at a price of $15. But if you would like

a Xerox copy of the entire PostScript magazine issue (which

includes the other additional material by the other authors listed

above), the PostScript issue is available separately for

$10. You may order it with a credit card through PayPal or through

the mail with a money order. See the instructions below.

***

A

packet comparing the two versions of Shadows is available: A

Detective Story – Going Inside the Heart and Mind of the Artist:

A Study of Cassavetes' Revisionary Process in the Two Versions

of Shadows. Available direct from the author through this site

for $15.

This packet contains the

following material (most of which was not included in the BFI Shadows book):

- An introductory essay

about the two versions of the film

- A table noting the minute-by-minute,

shot-by-shot differences in the two prints. (In the British Film

Institute book on Shadows, this table appears in a highly

abridged, edited version, at less than half the length and detail

presented here.)

- A conjectural reconstruction

of theshot sequence in the 1957 print

- A shot list for the 1959

re-shoot of the film

- The credits exactly as

presented in the film (including typographical and orthographical

vagaries indicating Cassavetes' view of the importance of various

contributors)

- An expanded and corrected credit listing that includes previous uncredited actors and appearances (e.g. Cassavetes in a dancing sequence; Gena Rowlands in a chorus girl sequence; and Danny Simon and Gene Shepherd in the nightclub sequence)

- Notes about the running

times of both versions and information about dates and places of

early screenings

- A bibliography of suggested

additional reading (including a note about serious mistakes in

previous treatments of the film by other authors)

Very little

of this material was included in the BFI book on Shadows due

to limitations on space. This 85-page (25,000 word) packet is not

for sale in any store and is available exclusively through this site

for $15.

***

The five books, two packets,

and issue of PostScript magazine may be obtained

directly from the author, by

using the Pay Pal Credit Card button below, or by sending a check or

money order to the address below. However you order the book or books,

please provide the following information:

- Your name and address

- The title of the book

you are ordering

- Whether you would like

an inscription or autograph on the inside front cover

Checks or money

orders may be mailed to:

Ray Carney

Special Book Offer

College of Communication

640 Commonwealth Avenue

Boston University

Boston, MA 02215

|

|

Credit

Card

|

| NEW! |

| Now

you can buy Ray Carney's works online using Visa or MasterCard.

|

|

Note:

If you pay by credit card using the PayPal button, please note in

the item description or comments section of the order form the exact

title of the item or items you are ordering (be specific, since

many items have similar titles), as well as any preferences you

may have about an autograph or inscription and the name or nickname

you would like to have on the inscription.

If you are confused by the PayPal form, or unsure where to enter

this information, you may simply make your credit card payment that

way, and separately email me (at the address below) any and all

information about what item you are ordering, and what inscription

or name you would like me to write on it, or any other details about

your purchase. I will respond promptly.

The PayPal form has a place for you to indicate the number of items

you want (if you want more than one of any item), as well as your

mailing address.

If you place your order and send your payment by mail, please include

a sheet of paper with the same information on it. I am glad to do

custom inscriptions to friends or relatives, as long as you provide

all necessary information, either on the PayPal form, in a separate

email to me, or by regular mail. (Though I cannot take credit card

information by mail; PayPal is the only way I can do that.)

If you want to order other items from other pages, and are using

the PayPal button, you may combine several items in one order and

have your total payment reflect the total amount, or you may order

other items separately when you visit other pages. Since there is

no added shipping or handling charge (shipping in the US is free),

you will not be penalized for ordering individual items separately

in separate orders. It will cost exactly the same either way.

These instructions apply to American shipments only. Individuals

from outside the United States should email me and inquire about

pricing and shipping costs for international shipments.

Clicking on PayPal opens

a separate window in your browser so that this window and the information

in it will always be available for you to consult before, during,

and after clicking on the PayPal button. After you have completed

your PayPal purchase and your order has been placed, you will automatically

be returned to this page. If, on the other hand, you go to the PayPal

page and decide not to complete your order, you may simply close

the PayPal window at any point and this page should still be visible

in a window underneath it.

If you have questions,

comments, or problems, or if you would like to send me additional

information about your order, please feel free to email me at:

raycarney@usa.net.

(Note: Due to the extremely high volume of my email correspondence,

thousands of emails a week, and the diabolical ingenuity of Spammers,

be sure to use a distinctive subject heading in anything you send

me. Do NOT make your subject line read "hi" or "thanks"

or "for your information" or anything else that might

appear to be Spam or your message will never reach me. Use the

name of a filmmaker or the name of a familiar film or something

equally distinctive as your subject line. That is the only way

I will know that your message was not automatically generated

by a Spam robot.)

Problems? Unable to

access the PayPal site? If you are having difficulty, it is generally

because you are using an outdated or insecure browser. Click

here for help and information about how to check your browser's

security level or update it if necessary.

|

|