This

page only contains excerpts from interviews Ray Carney has given.

In the two interviews excerpted below, Ray Carney discusses his

background and academic training. For more information about his

writing on independent film, including a new collection of interviews

with him in which he gives his views on criticism, film, and the

life of a writer, click

here.

Click

here for best printing of text

|

An

Interview with Ray Carney

by Cynthia Rockwell

for NewEnglandFilm.com

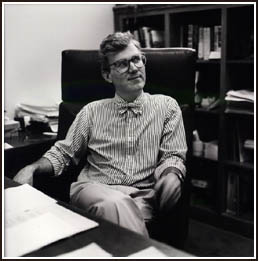

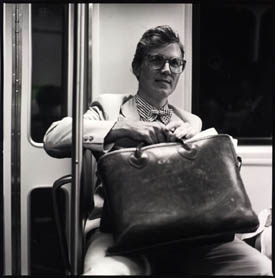

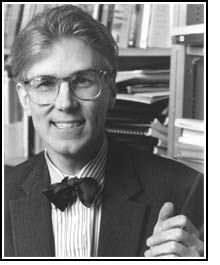

RAY CARNEY is well

known for his attacks on the Hollywood filmmaking establishment,

and the journalists,

critics, and film professors who,

in his view, support it—as he put it to me: “by conducting

sycophantic interviews with airhead movie stars, inviting celebrity directors

into the classroom, and generally functioning as unpaid publicists for

every studio blockbuster that comes along.” He is generally recognized

to be the world's expert on the life and work of the  “father of

the American independent movement,” actor-writer-director John

Cassavetes. He has just published three new books about the filmmaker:

Cassavetes on Cassavetes,

described as “Cassavetes’ spiritual

autobiography;” the British Film Institute Film Classics volume

on Cassavetes’ first film, Shadows, which reveals new

facts about the making of the movie; and a viewer’s guide to

the films titled John Cassavetes: The Adventure of Insecurity.

He is a Professor of Film and American Studies at Boston University,

Director of the Film Studies

program, and chair of graduate admissions. As a former student of his,

I wanted to begin our conversation with an exploration of his background

and training, and a few questions about how he got

into film and got interested in Cassavetes in particular. “father of

the American independent movement,” actor-writer-director John

Cassavetes. He has just published three new books about the filmmaker:

Cassavetes on Cassavetes,

described as “Cassavetes’ spiritual

autobiography;” the British Film Institute Film Classics volume

on Cassavetes’ first film, Shadows, which reveals new

facts about the making of the movie; and a viewer’s guide to

the films titled John Cassavetes: The Adventure of Insecurity.

He is a Professor of Film and American Studies at Boston University,

Director of the Film Studies

program, and chair of graduate admissions. As a former student of his,

I wanted to begin our conversation with an exploration of his background

and training, and a few questions about how he got

into film and got interested in Cassavetes in particular.

Cynthia Rockwell:

You've written several definitive books on John Cassavetes and his

work—can

you describe what it was that originally attracted you to his work?

Ray Carney: My taste in movies has always been a little weird. Probably

as a result of coming to them pretty late. As a kid and a teenager, I

lived far out in the country, and saw almost nothing. I went to a few

movies in college [at Harvard], but really only began to get interested

in film in my twenties, during my grad school years [at Rutgers]. But

not Hollywood movies! You need to know some background to understand

this. So bear with me, OK?.

Near the end of my college

years, I had this epiphany about art as the ultimate form of human

expression. All the time I was growing up, my

family had had no interest in art at all. None. My father was a businessman;

there was not one really good book or record in my house; and no awareness

that arts like ballet or opera even existed. I began college as a math

and physics major. I was a real science buff—pretty good at it

too. Had won prizes and awards and scholarships. A fellowship from the

National Science Foundation while I was in high school. The whole nine

yards. I knew what I wanted to do with my life. It was all mapped out

for me. But then magic happened. Due to an “artistic” Radcliffe

girlfriend who threw my life into intellectual and emotional turmoil,

I discovered painting, literature, drama, and the other arts. Meeting

her and suddenly having this world opened to me was like being hit by

a falling piano. I was mystified, bewildered, destroyed. It was a life-changing

experience. And that’s an understatement!

End of Mr. Math Whiz. I went

to grad school to take a Ph.D. in English literature, and by this point

was completely flipped out, totally obsessed

with art. Crazy. Uncontrollable. There’s no proselytizer like a

convert. I would invite friends to my house on Saturday nights and force

them to sight-read Shakespeare. I read the complete Faerie Queene out

loud to another girlfriend. It’s the longest poem in English—hundreds

of pages of tiny type and it took months. (She must have had the patience

of a saint to have put up with it.) I set myself these heroic goals.

I  attempted to read the complete works of all the biggies. Totally nuts!

I worked my way through Beethoven, Armstrong, Parker, Basie, Ellington,

and Goodman. I hacked a path through deepest, darkest, late Henry James.

I went to used record stores and got every LP Lenny Bruce had ever recorded.

I didn’t have much money, but even on a graduate student’s

budget, I managed to scrape together enough to go to the ballet every

week (sitting up in the fourth ring nosebleed seats at Lincoln Center

where the old ladies from the tour bus talk throughout the performance).

For a few years, I saw every Pinter or Chekhov play that came through

New York. Getting to a dance piece by Paul Taylor or George Balanchine

was more important than eating or paying the rent. attempted to read the complete works of all the biggies. Totally nuts!

I worked my way through Beethoven, Armstrong, Parker, Basie, Ellington,

and Goodman. I hacked a path through deepest, darkest, late Henry James.

I went to used record stores and got every LP Lenny Bruce had ever recorded.

I didn’t have much money, but even on a graduate student’s

budget, I managed to scrape together enough to go to the ballet every

week (sitting up in the fourth ring nosebleed seats at Lincoln Center

where the old ladies from the tour bus talk throughout the performance).

For a few years, I saw every Pinter or Chekhov play that came through

New York. Getting to a dance piece by Paul Taylor or George Balanchine

was more important than eating or paying the rent.

Am I making it clear that

this was some kind of insanity? I’ve

always been obsessive about anything I am interested in. I realized years

ago that if I weren’t interested in art, I’d probably be

into drugs or some other compulsive behavior big time. Too bad it’s

not making money or cleaning my house—I could use a little of that

kind of obsessiveness! Even now, I will fly into a city and see five

or six dance performances in a row or spend three consecutive days in

a big museum—all day, from opening to closing! I always warn anyone

who is foolish enough to come with me what they are in for. I will wear

anyone out standing in front of paintings! My friends are so patient

with me they should be canonized. Some people’s idea of fun is

to get a four-day pass to Disneyworld, mine is to spend four days in

a row in the Met or the National Gallery. I ran into Paul Taylor at an

intermission in City Center a few weeks ago, and told him how I impulse

binge on his works for three or four days at a time, matinees and evenings,

back to back. It was a comical conversation. Here I was talking to one

of my all-time heroes, and he smiled at me, I think he was laughing at

me, and said: “How can you stand it?” Of course, I told him

I couldn’t stand life otherwise. These sorts of experiences are

the only things that get me through most of the rest of life.

But I got off track. Back

to my salad days. Because of my art obsession, when I finally began

going to a few movies in my graduate school years,

I wasn’t looking for stupid sentimental story-telling and movie-star

glamour—but for the same kinds of experiences the literary and

musical works I loved gave me—turbulence, confusion, wildness,

challenge, mystery, shock, magic.

Maybe it comes down to the

fact that I got into film in a different way from most of the people

I know. Almost without exception, all of

the reviewers and directors I now know became interested in film because

at some point or other in their teens or twenties they felt this powerful

identification with some character or movie – or maybe with several

characters or movies. They saw Citizen Kane and identified with the loneliness

of the title character. They saw The Graduate and identified with the

powerlessness of the Dustin Hoffman character. They saw Star Wars and

felt like they were Luke Skywalker or Han Solo battling the Evil Empire.

They saw Edward Scissorhands and felt the Johnny Depp character was them.

They saw The Matrix or Titanic and felt in some deep part of their soul

that they were living Neo’s or Kate Winslett’s life. They

saw Thelma and Louise or Erin Brockovich and imagined that they were

just like them. They could outsmart the stupid plodding men in the world.

You get the idea. That wasn’t the way I became interested in movies.

I’ve never approached a movie that way, and don’t now. identification with some character or movie – or maybe with several

characters or movies. They saw Citizen Kane and identified with the loneliness

of the title character. They saw The Graduate and identified with the

powerlessness of the Dustin Hoffman character. They saw Star Wars and

felt like they were Luke Skywalker or Han Solo battling the Evil Empire.

They saw Edward Scissorhands and felt the Johnny Depp character was them.

They saw The Matrix or Titanic and felt in some deep part of their soul

that they were living Neo’s or Kate Winslett’s life. They

saw Thelma and Louise or Erin Brockovich and imagined that they were

just like them. They could outsmart the stupid plodding men in the world.

You get the idea. That wasn’t the way I became interested in movies.

I’ve never approached a movie that way, and don’t now.

Cynthia Rockwell:

What’s

wrong with identifying with a character?

Ray Carney: It’s a child’s way of thinking. It’s playing

with action figures, Halloween dress-up, a dolly tea-party,

not what appreciating art is about.

Cynthia Rockwell: What do you mean?

Ray Carney: You know, you

dress up your Barbie and “become her.” You

hold a tea party with your little friends and play mommy and auntie.

You take out your toy soldiers or your Hulk Hogan figure and slay the

world. That’s not what experiencing art is about. We know this

about other arts, but film appreciation is so infantilized that we forget

it. You don’t experience Paul Taylor’s Esplanade or

Picasso’s

Night Fishing at Antibes or Bach’s Goldberg Variations to

plug yourself into them that way, to feel better about yourself, to fantasize

that you are strong and mature and powerful. Those works make demands

on you. They test your powers of awareness. They expand your consciousness

in unexpected directions. They are not Rorschach blotches that you project

your fantasies of powerlessness into and get power by expanding within.

They are not about flattering you by allowing you to feel sorry for yourself

or to pretend you are more important than you really are. Art is not

about that. It’s not about cheering yourself up with flattering,

self-aggrandizing fantasies. That’s for kids. That’s

dressing up and playing pretend. That’s playing with action figures.

That’s reading a children’s story when you're eight or nine.

That’s the Halloween parade at school. That’s wearing your

Superman underoos. That’s pop culture. That’s Hollywood.

Cynthia Rockwell:

If you weren’t

interested in those things, why were you drawn to the movies at all?

Ray Carney: I was attracted

to complex, demanding, subtle emotional experiences that moved me into

new ways of feeling and thinking. I didn’t

find that in Hollywood’s cartoon-characterizations and emotional

button-pushing and still don’t. Those weren’t the kind

of movies I started going to or the kind of movies I go to now. But I

found it in a few foreign filmmakers: Bresson, Tarkovsky, Fellini, Ozu,

Rossellini, DeSica, Dreyer, Renoir, and some others. I became as consumed

with their work as I was with Picasso’s or Parker’s. By sheer

chance, I also stumbled into a few of what are now called “independent

films”—though the term didn’t exist in those days—works

by Paul Morrissey, Barbara Loden, Bruce Conner, Mark Rappaport, Robert

Kramer, John Korty. Cassavetes was in that group: Faces, Husbands, A

Woman Under the Influence. The American films were entirely different

from the foreign ones, but just as consciousness-altering and exciting.

The rest, as they say, is

history. As I look back on it, I realize that my timing couldn’t

have been better. It was the early to mid-seventies, the greatest era

in all of American film. I was incredibly lucky. The

stars must have been aligned.

Cynthia Rockwell: Great story about meeting the girl.

Ray Carney: Yes, but, let

me unsay everything I have told you. To tell the story this way is

misleading. It makes it all sound much more organized

and systematic than it really was. Meeting Aida, that was her name, was

more a butterfly in Brazil experience. She was the butterfly and there

was a hurricane a few years later, but I don’t know exactly how

the two are linked. That’s where the story makes it too neat. By

the time the changes were taking place in my life, she and I had broken

up. And I didn’t know the storm clouds were storm clouds at the

time. A lot of the art stuff was just a crazy new interest of mine along

with a lot of other new interests. The things that happen to you in your

twenties. My point is that my life was more random, more open-ended,

than I am making it sound—less a path than a jungle of criss-crossing

interests. But when you tell it, it becomes orderly. It’s a lesson

for artists to learn from. Stories clean things up too much. They make

them neat where they should be messy. My story is a lie because it seems

too orderly. That’s why we have to get the mess back into our art

and acknowledge it in our lives.

Cynthia Rockwell: Were there any teachers that inspired you?

Ray Carney: I’ve always felt incredibly lucky in the teachers

I’ve had—way back to middle school. Maybe it’s why

I became a teacher. My favorite bible parable is the sower of seeds one—you

know where some seed falls by the wayside, some falls on rocks, and some

falls on fallow ground. That’s what is always going on. Teachers

plant seeds, but the soil has to be ready to receive them, and sometimes

it takes a long, long while for them to grow. There are things my teachers

said to me years ago that I am just now understanding. And sometimes

some sort of magical meeting of minds happens because you are ready for

it, that wouldn’t have happened with the same two people a year

before or a year later. It’s like love. I’ve had famous teachers—one

grand old man named Reuben Brower who taught literature in a small seminar

at  Harvard. He was legendary, a kind of Benjamin Jowett of Harvard—refined,

distinguished, classically educated. People fought to get into the course.

But most of what he said didn’t take with me. I learned a little

from him, but not very much. I was just a dumb freshman from a public

high school and wasn’t ready for what he offered. The opposite

happened in grad school. I had a teacher, Richard Poirier, who most of

the other students didn’t get along with, but for me, everything

he said was gold. Everything. If he talked about the weather I thought

it was profound. If he had taught farming, I would have taken notes. Harvard. He was legendary, a kind of Benjamin Jowett of Harvard—refined,

distinguished, classically educated. People fought to get into the course.

But most of what he said didn’t take with me. I learned a little

from him, but not very much. I was just a dumb freshman from a public

high school and wasn’t ready for what he offered. The opposite

happened in grad school. I had a teacher, Richard Poirier, who most of

the other students didn’t get along with, but for me, everything

he said was gold. Everything. If he talked about the weather I thought

it was profound. If he had taught farming, I would have taken notes.

Teaching and learning are

very mysterious processes. They aren’t

always about what they seem to be about. Sometimes trivial things matter

much more than the ones that are supposed to be important. When I had

Brower, the class I remember most vividly was one where he got off the

subject for about ten minutes and started talking about an opera—I

think it was Don Giovanni—he had listened to the night before at

home. His words made an incredible impression on me—not only since

I had never heard an opera before, in fact I hardly knew what one was—but

because they opened to view of a world where that was what you did at

home at night. I wanted to live that life—one where you read Shakespeare

or Henry James instead of watching television in the evening. The miracle

is that now I do lead that life. But in its early stages a lot of learning

is childish, monkey-like imitation. I was no Brower, but I saved up my

money and bought a copy of Don Giovanni and listened to it in my dorm

room, and pretended I was him.

The only other class with

him I remember, we were reading a scene in The Tempest where the sailors

are telling jokes. Brower asked the class

what we thought of the jokes. Since it was Shakespeare, we figured we

knew the right answer so we came up with all of these observations about

how brilliantly witty and profound they were. Then he dropped the bomb,

and told us they were stupid and not funny—that Shakespeare was

that smart—that when he had dumb characters, he gave them dumb jokes! It rocked my world—which is undoubtedly why I still remember

it so many years later. I suddenly realized that art wasn’t necessarily

about idealization and perfection and beauty but about truth—however

rough or unpalatable or stupid. Art didn’t have to be up on Olympus.

It could include clumsiness, awkwardness, and bad jokes. Things that

were in my life. Of course it took me a long time to get from the sailors

to Cassavetes’ salesmen in Faces or the off-balance balance of

Suzanne Farrell in Agon, but you might say that everything I’ve

written about the poetry of imperfection comes out of that class with

Brower.

I’ve also had non-academic teachers who were incredibly important

to me—one man named Philip Kapleau and another named Walter Nowick.

I spent a few years on a commune and after that in a couple Zen Buddhist

monasteries and they were the teachers. They would give brief talks to

the whole group—sometimes fifty other people would be sitting there,

but it was as if they were speaking to me alone with every word. As if

they could see into my heart and say the thing I needed to hear at that

moment. That’s what real teaching is. What it means is that I was

ready for what they were saying. I’m a believer that a teacher

comes along when you are ready. And I believe the converse too: that

if you are ready, everything is a teaching. Of course, everything is a teaching, day and night, in class and out of it. Our problems, our

hurt feelings, our pains, our confusions are all lessons—if we

have ears to hear. It’s so easy to close our hearts.

Cynthia Rockwell: You know so much about various arts from jazz to dance,

and include them so much in your Boston University courses, that I wonder

how you learned this material. Did you take courses in different arts?

Ray Carney: No. I have to

confess I learned everything in a totally slipshod, haphazard way.

Over the years, I’ve sat in on a few lectures

in various subjects here and there, of course, but I haven’t officially

enrolled in any formal courses since the ones I took to get my Ph.D.

I really think you can teach yourself anything—from auto mechanics

and computer repair to theoretical physics—if you are motivated.

When someone says they can’t learn something, it’s almost

always because they don’t really want to learn it. It’s not

important enough to their lives at that moment. All learning is emotional.

When your emotions are involved, when your life depends on something—imaginatively

or physically—you can master almost any situation. Ray Carney: No. I have to

confess I learned everything in a totally slipshod, haphazard way.

Over the years, I’ve sat in on a few lectures

in various subjects here and there, of course, but I haven’t officially

enrolled in any formal courses since the ones I took to get my Ph.D.

I really think you can teach yourself anything—from auto mechanics

and computer repair to theoretical physics—if you are motivated.

When someone says they can’t learn something, it’s almost

always because they don’t really want to learn it. It’s not

important enough to their lives at that moment. All learning is emotional.

When your emotions are involved, when your life depends on something—imaginatively

or physically—you can master almost any situation.

But you get to a point in

your life when courses seem too slow and teachers don’t seem daring and original enough to stimulate you. So you

read books. I’m a crazy reader. I love reading. The thrill never

goes away. What an astonishing invention writing is, a book is! I still

can’t get over it. Reading your way through a subject can be a

very active and exciting process when you’re highly motivated—you

don’t read passively like you do when you’re a student. When

your life is at stake to master something before you go—and whose

life isn’t at stake in that way?—you test your wits against

each author, seeing where one disagrees with another, and where you can

out-think them, pitting one against the other, trying to answer fundamental

questions.

I love to read! I’ve been on a Henry James jag for about five

or six years now. Re-read all of his novels and short stories.

It’s my third or fourth or fifth time through them at this point,

but I can’t get enough of them. I’m also a compulsive note-taker—scribbling

notes in the margins of my books or in a series of tablets and notebooks.

One of my TAs saw one of my James books and told me I was the John Madden

of marginalia! That’s a good comparison. You can understand a lot

of things that seem very mysterious by drawing circles and arrows around

parts of them. I have file cabinets full of notes that will never see

the light of day. I think I’m into working on something like tablet

number twenty-two in my current James binge.

Lately I’ve also been on a pretty big microbiology kick too. I

bought some Biology textbooks that were remaindered because they went

into new editions and picked up ten or twenty other books and started

teaching myself organic chemistry and cell biology. It’s better

than a three-dimensional chess game. Cell structure and energy

conversion are pretty interesting stuff. Really amazing actually. You

can have the Alps and the Matterhorn, right now protein folding, and

amino acid creation, and the DNA major grove are my sublime.

I read a lot of books about

art, but I stay away from most criticism. I think the real teachers,

the only ones that I trust, are the artists.

That’s what I thought when I was into math and physics also. There

was nothing that could top reading the stuff the discoverers wrote: Euclid,

Euler, Newton, Gauss, Michelson, Einstein, Planck. If you really want

to know what it feels like to be Michelangelo, read his letters on painting

and sculpture. If you really want to know what it was like to be Beethoven,

read accounts of things he said by people who talked with him. But the

most important lessons are not from an artist’s writing but from

looking at his or her work and getting it to teach you what you need

to know.

The ultimate “texts” to learn art from are the works themselves.

I learned about Shakespeare’s life not from a biography, but the

plays. You can feel the high-spirited sassiness of his youth in Midsummer

Night’s Dream, his middle-aged discouragement and disillusionment

in Hamlet  and Lear, and his final acceptance of what can and what can’t

be in the late romances. Watching Paul Taylor’s Esplanade and George

Balanchine’s Jewels taught me more about expressive abstraction

and narrative structure than any art course ever did. Wordsworth’s

Prelude and Henry James’s Ambassadors taught me the function of

style. Louis Armstrong and Billy Holiday taught me about tone and timbre.

The great film teachers in my life were named Bresson and Tarkovsky and

Cassavetes—and dozens of others of course. and Lear, and his final acceptance of what can and what can’t

be in the late romances. Watching Paul Taylor’s Esplanade and George

Balanchine’s Jewels taught me more about expressive abstraction

and narrative structure than any art course ever did. Wordsworth’s

Prelude and Henry James’s Ambassadors taught me the function of

style. Louis Armstrong and Billy Holiday taught me about tone and timbre.

The great film teachers in my life were named Bresson and Tarkovsky and

Cassavetes—and dozens of others of course.

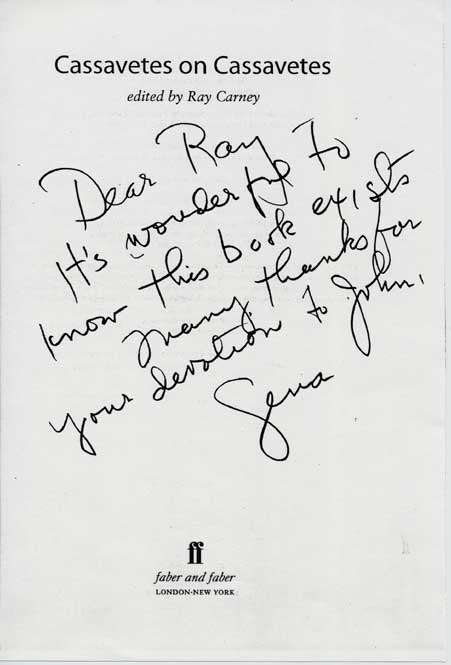

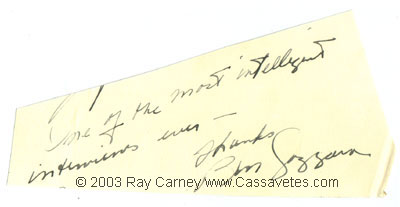

Cynthia Rockwell: Your newest book, Cassavetes

on Cassavetes, has an

interesting structure. It is a posthumous autobiography of sorts, drawn

from years of archived interviews with the filmmaker, but interwoven

with Cassavetes' own words is a considerable amount of your own description

and critique of the man's work and methods. Was the book always conceived

as a biography or did the concept evolve over years of research?

Ray Carney: If you don’t toss and turn in your sleep and change

your mind a trillion times while you’re working on a project like

this, you aren’t alive. If you don’t rejoice on some days

at your own brilliance and despair on others about your stupidity, you’re

not allowing yourself to learn anything. Everything changes every day.

I thought I knew all there

was to know about Cassavetes when I began. After he died I spent eleven

years talking to people who worked with

him. And reading and re-reading things he had said. Reading transcripts

and listening to tapes no one had ever heard before. Every time I talked

to another person, I saw new things. Everything I thought I knew turned

out to be wrong. My understanding of the films changed totally. I realized

that they were much more personal than I had imagined. A lot of the events

in them were veiled portraits of things in his life or emotional events

connected with his marriage to Gena Rowlands—though Cassavetes

threw viewers off the scent by casting Rowlands as himself! I kept rewriting

the headnotes up until the night before the book went to the printer.

I’m still rewriting them—scribbling things in my own copy

of the book—as I realize new things. I have hundreds of pages of

new ideas. Amazing stuff. No one will ever see that material, but writing

through my confusions is the only way I can come to grips with them.

I feel incredibly lucky to

have picked a filmmaker who was complex enough to bear this kind of

scrutiny without becoming boring or conventional.

There are very few questions worth devoting years of your life to. Most

of them are religious and have to do with life and death. But where art

comes from and how it works its magic is on the same level. How did Rembrandt

get so much of what it is to be human into his portraits? Where did Bach’s

music come from? Where is Shakespeare in his plays? The Cassavetes

on Cassavetes book is my attempt to grapple with these sorts of questions.

How is a great work of art made? What does it cost emotionally? What

confusions does it embody? The headnotes are my stabs at answers. It

really is the mystery of life itself—what makes it so magical,

rich, and strange. What luck to be able to write about that.

Cynthia Rockwell: In Cassavetes

on Cassavetes, the filmmaker mentions

several directors he admires, including Frank Capra and Carl Dreyer,

both of whom you've also written books about. Did Cassavetes inspire

you to study these filmmakers or does this simply reflect a connection

between their work and your own personal artistic interests?

Ray Carney: I guess great

minds think alike. But seriously, I just write about things that I

love and don’t understand. It’s no different

from obsessing about a person you are in love with. You can’t stop

wondering. What makes them tick? What makes them so amazing one minute

or so annoying the next? Writing is just a way of thinking and feeling

more clearly than day-dreaming.

Capra may seem like the odd

man out in all this talk about “art,” but

I find his work complex and tragic. When I went to the library to try

to read something about it, all I could find was this ridiculous, reductive

pop culture analysis—all that stupid stuff about how he believed

in the American dream and the common man, as if he were the cinematic

equivalent of Norman Rockwell. That had nothing to do with my experience

of his films. Norman Rockwell doesn’t make me cry. So I realized

I’d have to write my own book if I wanted to figure out why they

affected me so deeply. You know the saying—if you want to go to

a party, give a party? Well, I wanted to read a book about melodramatic

expression, so I wrote one.

Cynthia Rockwell: While it's clear from the Cassavetes

on Cassavetes and Shadows books that you greatly admire Cassavetes and his work, you

also make a point to describe how Cassavetes could be a pretty awful

man at times. Do you include this information simply to give a fair assessment

of the man's life, or do you think it relates to his work in some way? Cynthia Rockwell: While it's clear from the Cassavetes

on Cassavetes and Shadows books that you greatly admire Cassavetes and his work, you

also make a point to describe how Cassavetes could be a pretty awful

man at times. Do you include this information simply to give a fair assessment

of the man's life, or do you think it relates to his work in some way?

Ray Carney: Stanislavski’s My

Life in Art meant a lot to me as

a college student because it went behind the scenes to show what it really

took to make art. Not the Mickey Rooney “let’s-put-on-a-play” version

of creation, but the real doubts, fears, and pains that go into doing

anything difficult and brave. I didn’t want to simplify things

in the Shadows or the Cassavetes on Cassavetes books. There are a lot

of different people, different moods and feelings, in every one of us.

A lot of contradictions. We can be good and bad, generous and selfish,

perceptive in lots of ways and cluelessness in others. My portrait of

Cassavetes is cubistic. It’s fragmented and unresolved. That’s

the only way it could be true. It’s up to the reader to decide

how to feel about Cassavetes in the end.

Cynthia Rockwell:

In addition to being a respected critic and author, you are a professor

of film

studies at Boston University with a teaching

style that many of your students describe as ”inspirational.” Can

you draw any connections between your own teaching philosophy and Cassavetes'

philosophy of filmmaking? Or your approach to film criticism?

Ray Carney: I don’t know anything about the “inspiring” stuff.

I’m just a very emotional person. In fact, a basket case—pretty

close to the edge a lot of the time—though I usually manage to

keep it pretty well-concealed. All my teaching is just my own attempt

to understand these amazing things we call works of art. It’s an

extended conversation with students in which I often think I learn more

from their comments than they do from mine. All I do is point out things:

Did you hear that tone in her voice? Did you see how he hesitated in

his response? Did you notice the way the next shot wasn’t what

we expected? Do you see how that scene changes our understanding? I’m

just like one of those architectural tour guides who point out things

to look up at. It’s up to the student to make something out of

those millions of little observations.

Cynthia Rockwell: Do you think there's an advantage to studying or working

in film in New England, outside the hubs of New York and Los Angeles? Cynthia Rockwell: Do you think there's an advantage to studying or working

in film in New England, outside the hubs of New York and Los Angeles?

Ray Carney: Art can be made

anywhere. Some of the greatest contemporary films are being made in

Iran. New York has lots of artists to talk to

and lots of art to see, and that’s in favor of it. But it’s

a fashion-conscious city, addicted to money, power, and business values,

and impossibly expensive to live in for a starving artist. That’s

all against it. Why anyone would live in Los Angeles, I’ll never

understand. There’s nothing there. You might as well choose to

live on the moon. But I guess you could make art there too. It would

just be harder, since the air is so thin and life is so unreal—which

is probably why art hasn’t happened to the city yet. Lester Horton

is the exception that proves the rule. Boston is not bad, though it’s

also very expensive, and the fashionable parts of the city are way too

tame, too yuppified and conservative for my taste. Too Harvardized. What

an over-rated university! Boston has too many intellectuals and stockbrokers—if

there’s a difference anymore. Neighborhoods like Dorchester and

Roxbury and Chelsea are better places to live in that respect. You escape

from the cultural craziness just a little.

I’m interested in films that are in touch with the lives of people

who are not intellectuals or artists. Works with roots in a community

of caring people. Works anchored in local neighborhoods and ways of being.

All the things Hollywood avoids and hates with a passion. They know it’s

always easier to present grandiose David Lynch metaphors than it is truthfully

to show how a particular mother and son really interact on a specific

day.

Cynthia Rockwell: Can you list any contemporary filmmakers whose work

you admire?

Ray Carney: Tom Noonan, Abbas

Kiarostami, and Mark Rappaport are three favorites, though Noonan has

only been able to release two movies [What

Happened Was... and The Wife] in ten years. He filmed a third three or

four years ago, but doesn’t have enough money to finish it. And

even if he does, no distributor has shown a jot of interest in picking

it up. Then there’s Charles Burnett, Su Friedrich, and Jay Rosenblatt.

Killer of Sheep, To Sleep with Anger, Sink or Swim, Rules

of the Road,

Period Piece, and Human Remains are all amazing movies. Rob Nilsson and

Gordon Eriksen are also good filmmakers with roots in local communities.

I don’t read newspapers or newsmagazines or watch broadcast TV,

since I am not interested in wasting my time keeping up with the so-called “news,” but

these artists give me the emotional news I need to stay alive. They are

writing the real history of the present—beyond anything that will

ever appear in the New York Times. As Ezra Pound put it so long ago,

they write the news that stays new—forever.

*

* *

Ray

Carney Interviewed by

Features

Editor Mary Alice Blackwell

Printed in The Daily Progress newspaper

in Charlottesville, Virginia

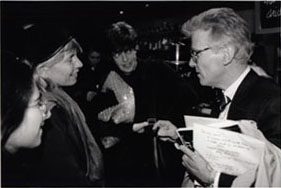

RAY CARNEY will be introducing films and

conducting an on-stage question and answer session with Gena Rowlands

following a screening of Gloria at this years Virginia Film Festival. He is

generally recognized to be the world's expert on the life and work of

the so-called father of the American independent movement, actor-writer-director

John Cassavetes. He has just published three new books about the filmmaker:

Cassavetes on Cassavetes, described as a profound spiritual autobiography

of the filmmaker; the British Film Institute Film Classics volume on

Cassavetes first film, Shadows, which re-constructs the lost

first version of the film from conversations with the director before

he died; and a viewers guide to the films titled: John Cassavetes:

The Adventure of Insecurity. Prof. Carney will be signing and selling

copies following several of the Festival events, and all three books are

available at the University Bookstore.

He is a Professor of Film and American Studies

at Boston University, Chairman of the Film Studies program, and Director

of graduate admissions. More information about his work is available at

the web site devoted to independent film and art he maintains at: http://www.Cassavetes.com.

How

did you get involved with the Virginia Film Festival this year? How

did you get involved with the Virginia Film Festival this year?

Every

Film Festival has a personality. Some are week-long cocktail parties;

some extended ski vacations; some high-finance, business, and deal-making.

I am invited to help out with events at dozens of Festivals a year, but

to tell you the truth, I'm not a serious enough drinker, skier, or schmoozer

to be interested in attending most of them. The Virginia Festival is a

time for relaxed thought, deep reflection, and intelligent conversation

about the art of film. The association with the University of Virginia

makes a real difference. The audiences take movies seriously, and the

themes Richard Herskowitz [the director] organizes each Festival around—this

years its Masquerades—provide an intellectual focus for serious

thought and discussion. Of course, that doesnt mean the Festival isn't

entertaining. Ideas can be a lot of fun!

Did you have an input into the selection

of films?

I

made a few recommendations about which Cassavetes films might work well

with the theme and made a few suggestions on where to get them. Cassavetes

work plays once in a while on cable television, but it is still hard to

catch on the big screen, the way movies were meant to be seen. Fortunately,

Richard Herskowitz is very resourceful at locating prints, one of which,

I believe, is being flown in from Vancouver, Canada specially for the

event.

Weren't you in Charlottesville before?

I

was here a few years ago to introduce some screenings and participate

in a panel discussion with Roger Ebert and Mark Edmundson on Irony.

The topic seems prescient given recent reflections in the light of the

events of Sept. 11th on the frivolousness and irresponsibility of Hollywood

and American culture in general. The perpetual wink, nod, and smirk of

Tarantino and the Coen brothers seems even more out of touch, even more

adolescent and immature in the world we were ushered into on that day.

A little background on you. You are

such a well respected scholar on film, what got you started in this line

of work? It seems you would make a fine screenwriter.

I

don't know about the screenwriting observation. I find writing in my own

voice is hard enough. I don't think I could manage to do it in five or

ten other voices.

It's

a bit of a mystery how anyone ends up doing anything, isn't it? You walk

a zig-zag path, shaped by happy accidents, and end up some place you never

could have anticipated. I began college as a math major, shifted to physics,

then went to philosophy and psychology. I then took a Ph.D. in English

literature and wrote my dissertation on William Wordsworth. My first full-time

academic job was teaching literature in an English Department.

I

really wasnt that interested in movies. I have to blame Cassavetes for

getting me into film criticism and analysis! After I had stumbled into

a few of his films more or less by accident, I went to the library to

find something to read about them. He had been making films for almost

twenty years at that point, but there was almost nothing in print

about him—beyond brief reviews—not a single decent book or essay.

So I decided to write something myself. I used to joke him that I wished

my name were Pauline Kael or Vincent Canby, because it would have done

him a lot more good than having me write about him! I was just an unknown,

unimportant graduate student at the point I began my first book. I've

written lots of others since then—about other things beyond Cassavetes.

But I didn't abandon my other loves. Right now I'm working on one book

about Henry James and another about American painting.

On Cassavetes: What made you choose

Cassavetes? Was it the man, his movies, or his pioneer methods? What was

it that sparked such an interest that your were willing to spend so many

years on research. (I think it was a great choice. But I always wonder

why writers pick their subjects when there are so many to choose from.)

It

may sound strange to say it, but I write out of my bewilderments, my confusions,

my doubts. To try to figure something out. To see what makes it tick,

and to try to find out what I think about it. If I understand something,

it's the last thing I would want to sit down and spend years of my life

working on. It would be boring to write about.

I

walked out of the first Cassavetes movie I ever saw. It was Faces,

and I was only a college student at the time. The movie was just too much—too

confusing, too strange, too weird emotionally. It didn't play by the rules

of the film game. I couldn't figure out the characters. They wouldn't

stand still for me to understand them. They kept changing. I couldn't

put handles on their situations or my own emotions. Scene after scene

kept surprising me. And my own responses kept bewildering me. In short,

the movie threw me for a loop. It was the darnedest experience.

A

few years later, I saw a couple more Cassavetes movies, though I didn't

realize they were by the same filmmaker until later: Minnie and Moskowitz

and A Woman Under the Influence. A Woman Under the Influence

affected me incredibly deeply. Near the end of the film, in a scene that

has been cut from current prints, where the children run down the stairs

the third time, I remember thinking: I don't know whether I like this

movie or hate it, and I don't know whether to laugh or cry or what at

this scene, but this is the most amazing experience I've ever had in a

movie theater. The movie was intellectually flabbergasting and emotionally

unclassifiable. It was a tragedy in many respects, but, paradoxically,

it made me feel grateful to be alive, to be able to see and feel all the

things that were in it. After the screening was over, I couldn't talk.

I wanted to be alone. I walked away from the theater, down a side street,

went up on a deserted hill where there was a darkened church, quiet and

all alone, and whooped—though I didn't understand why. I just knew

I had lived through something amazing, and had to do something to get

it out.

The

next day was when I made my fateful visit to the library, to discover

how little was written about Cassavetes, and how bad the little bit that

existed was. I had to write the book to work through my confusion.

Also,

how did you meet Cassavetes? Also,

how did you meet Cassavetes?

Though

time seems compressed when you describe something, it took me a year or

two more to get started on it, and I didn't actually finish the book for

a few more years after that. Before I could write anything, I had to search

out his movies and try to see as many of them as possible. That took a

long time—about four or five years in all. It was before the video

revolution and I was teaching at a small college in Middlebury, Vermont,

which was not exactly a Mecca for obscure independent films, so once I

had resolved to write something, I had to travel to Boston and New York

to try to catch screenings when I could. Id do anything to see his movies.

I was a lowly paid beginning faculty member and spent most of my money

traveling. Just crazy, I guess. I remember going to New York and Boston

(at my own expense!) more than once to catch a single Saturday or Sunday

afternoon museum screening and then going home. It wasnt always a happy

experience, I flew to L.A. one time because Cassavetes was directing a

play he had written, and it was only going to be there for about a month.

But when I arrived I couldn't get a ticket for the day or two I was able

to be there, and didn't have enough money to stay any longer. Young and

dumb.

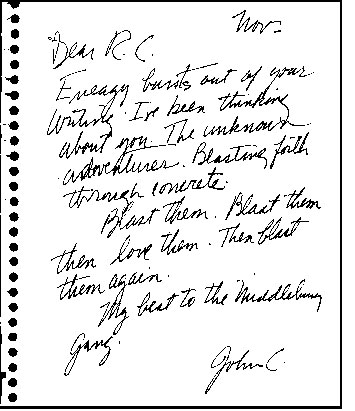

I only got

to know him in the final decade of his life. Our first real contact began

sometime in 1980 I think it was when I sent him the American Dreaming

manuscript. It was the first book in any language about his work. When

he received a four-inch-thick stack of typewriter paper in the mail, I

think he realized that I wasn't just another gushing fan who says how

much they love his work . He offered some corrections to my manuscript,

which I then rewrote, and started a correspondence with me via letter and

phone call. I visited him on the West Coast later on. Going into his house

was like entering a ghost town - all those memories of scenes from Faces

and Minnie and Moskowitz and Opening Night and Love

Streams. The bar where Richard tells Maria he wants a divorce, the

room where Chettie dances with the ladies, the breakfast nook where Jim

greets his wife and children, the dining room with the crystal chandelier

where Myrtle goes for the seance, the kitchen in Robert Harmon's house.

Everything was a set from one of his movies.

But it is indicative of how

reluctant America was to recognize his work during his lifetime that it

took three or four years to get my book published. He really just didn't

exist as a director at that point. The film professors who were the readers

for the kinds of presses I sent the manuscript to didn't take him seriously.

Most of them still don't. The first four or five presses I submitted the

book to told me that Cassavetes wasn't a "real" director, but

just an actor who clowned around with his friends on screen. The movies

were regarded as total, disorganized messes. Why would I want to write

about them or take them seriously at all? It was a first-hand illustration

of Clement Greenberg's adage that "all profoundly original art looks

ugly at first."

Here

it is eleven years after Cassavetes death, and he is finally being taken

seriously, at last. In some ways, it was better before he was accepted.

There was a purity to the group of true believers. Once something becomes

fashionable, it subtly changes the experience. The private, frightened,

shaking ecstasy becomes an accepted religion. What is it Emerson says?

The religion becomes a church—a set of rules and ceremonies and codified

beliefs that drain the life from the original experience. I'm in favor

of keeping the mystery alive. Art is nothing if not mysterious.

Anyway,

he and I had a fascinating series of conversations about film in that

final decade—in person, on the telephone, and in letters. Those interactions

and tons of other material are the basis for my Cassavetes on Cassavetesand Shadows books, which reveal things he told me about his

life and work that he never told anyone else. I call them his Rosebud

conversations. Really amazing stuff, where he told me secrets about

how he made the films. I've thought about why he said some of these things

to me and I think I finally understand. He was sick, knew he didn't have

long to live, and wanted to straighten out the record on some things.

Also I was a very safe person to talk to, since I lived on the east coast

far from where he was, and also because he knew I wasnt a journalist

and wasnt going to rush into print with anything he said. It was strictly

for posterity. Thats why I held onto these things for so many years.

They sat in my file cabinet and I was so sad that he wasnt around that

I didn't even want to look at them for a long time. But I won't say any

more. Youll have to read the books to find out what he said about his

work—or go to my web site (www.Cassavetes.com), which has excerpts

from my writing.

This

page only contains excerpts from interviews Ray Carney has given. In the

two interviews excerpted, Ray Carney discusses his background and academic

training. For more information about his writing on independent film,

including a collection of interviews with him in which he gives his views

on criticism, film, and the life of a writer, click

here.

|