Tillich's Theological Influence on Langdon Gilkey

(1919-2004)

|

|

|

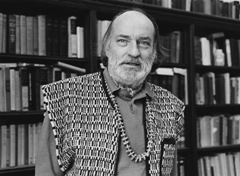

Langdon Gilkey (from

here) |

The theological influence of Paul

Tillich on the thought of American theologian Langdon

Gilkey is a fascinating and ambiguous one. Gilkey was an

influential Protestant theologian during the latter part

of the twentieth century, who spent most of his academic

career at The University of Chicago Divinity School.

Though a prolific academic

theologian, Gilkey is perhaps best remembered for his

autobiographical book Shantung Compound: The Story of

Men and Women Under Pressure (1968), which details

his internment at a Japanese POW camp during the second

World War. Shantung Compound not only recounts the

harrowing travails of life in an internment camp, it

also discloses the significant ideological shifts that

this experience precipitated for the young Gilkey.

Perhaps most importantly, the experience in Shantung all

but dissipated the humanistic optimism of his liberal

upbringing. For life “under pressure” in the internment

camp revealed his fellow prisoners (and himself) at the

nadir of their selfish, ignoble selves. Where Gilkey had

hoped to find some modicum of goodness and humanity he

found instead only a bleak, Hobbesian image of the human

condition. With regard to his theology, this experience

served to illuminate the power and truth of the

traditional Christian symbols of the Fall and original

sin. Gilkey’s experience in WWII left him perfectly

primed for the “crisis” theology of Neo-orthodoxy that

was in vogue at the time.

After the war, Gilkey went on to

pursue doctoral studies at Union Theological Seminary

and Columbia University, where he worked under Reinhold

Niebuhr and Paul Tillich. Though he worked more closely

with Niebuhr, Gilkey writes of his encounter with

Tillich: “at once I was puzzled, fascinated, and lured

by his very different way of viewing existence, namely,

ontologically rather than ethically as did Niebuhr. Soon

I felt I was beginning to understand him; for a time I

became his assistant and interpreter in his classes on

systematic theology—and a devoted listener in his

seminars on Augustine and Luther. I did not suspect

then—nor did I for a number of years—that a new

theological blood type, if I may put it that way, was

entering my arteries, one that would later become almost

dominant” (Gilkey, 1990: xi). Gilkey goes on to note, “I

did not become explicitly aware of how my own modes of

theological reflection were dependent on him until the

mid-sixties…” (Ibid: xii).

Gilkey’s dissertation on the

doctrine of creation served as the basis for his first

book, Maker of Heaven and Earth: The Christian

Doctrine of Creation in the Light of Modern Knowledge

(1959). As we shall see, this work exhibited a curious

amalgamation of theological and philosophical influences

ranging from Barth to Whitehead to Tillich. Setting

aside the philosophical influence of Whitehead, the

divergent theological currents at work in the book made

for an awkward, if not incoherent theological position.

However, in order to understand

Gilkey’s ambiguous theological stance in Maker of

Heaven and Earth, it is important to place this work

in proper historical context. For a brief time after the

First World War it was common for theologians as diverse

as Tillich and Barth to be lumped together under the

banner of “Neo-orthodoxy.” There were, of course, some

common elements amongst the theologians who (for a time)

bore this epithet, e.g. they often wrote in the

philosophical idiom of existentialism and shared—in

varying degrees of outrage—a general dissatisfaction

with the liberal theology of the later 19th century.

Nevertheless, over time it became vividly apparent that

these similarities were more surface-level than

substantial—indeed, Barth and Tillich could not be more

divergent in their approaches to theology.

Gilkey’s handling of the doctrine

of God in Maker of Heaven and Earth exhibits

perhaps the clearest instance of Tillich’s influence.

Throughout the text, Gilkey insists, in good Tillichian

fashion, that God is “Being-itself,” and therefore

cannot be understood as one entity alongside others. For

instance, Gilkey cites the first volume of Tillich’s

Systematic Theology, and repeats Tillich’s assertion

that “A conditioned God is no God” (Gilkey, 1959: 111).

However, only several pages later we find Gilkey

arguing, this time in a robustly Barthian vein, that the

Divine freedom is such that God is totally free to act

upon his creation in various ways to accomplish God’s

purposes. Consequently, God is not just Being-itself,

but also the God of Heilsgeschichte, or salvation

history. Gilkey writes, “the essence of the biblical

view of God is that He is not confined merely to that

ontological relation to the world which He has as

Creator. Rather He is ‘free’ to have other sorts of

relations to creatures, depending upon His

‘intention’…the biblical God is the God of history, who

acts within certain unique events of history and is thus

known through His ‘mighty deeds’” (113).

Throughout Maker of Heaven and

Earth, Gilkey seems to want to have it both ways

with respect to the Divine nature: God as both

Being-itself—and therefore eternal, impassible and

unconditioned—and the temporal, loving, personal God of

the Bible who supernaturally intervenes in certain

events in human history. Now, in Gilkey’s defense, the

attempt to form a synthesis between “the God of the

philosophers” and the “God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob”

is an ancient one, and he has a significant portion of

the tradition on his side in attempting to conjoin the

two divergent models of God. That said, for as long as

the tradition has attempted such a synthesis it has

always been plagued by the specter of philosophical

incoherence. As it happens, Tillich is one of a handful

of Christian theologians in the tradition to come out

and frankly name the incoherence, and then choose

cleanly between the two conflicting models of God (See

Tillich, 1951: part II). It follows from Tillich’s

ontological claim that God is Being-itself that the

personalist images of God in the biblical tradition must

be interpreted symbolically. Unlike many other

theologians, Tillich refused to proceed as if the

tension between Jerusalem and Athens could be dissolved

with a few fancy flourishes of dialectical language, or

by waving the term “paradox” at it like a magic wand.

It seems odd then that Gilkey, who

studied under Tillich and cites the first and second

volumes of the Systematic Theology in his

Maker of Heaven and Earth, nevertheless carries on

as if casually yoking the God of the bible with a

Being-itself model of God were not a fraught

philosophical move; especially given that Tillich’s

entire system hinges upon an unusually clear distinction

between these two models of God. Over time, however,

Gilkey came to recognize the considerable conceptual

problems with his position in Maker of Heaven and

Earth.

In his wide-ranging book The

Word As True Myth: Interpreting Modern Theology,

eminent historical theologian Gary Dorrien dedicates two

chapters to the unfolding of Gilkey’s thought amidst the

tempestuous theological tides of the 1950’s and 60’s. In

explicating the historical and theological milieu in

which Gilkey was trained, Dorrien illuminates the

connection between Gilkey’s muddled theological position

in Maker of Heaven and Earth and the broad

theological trends of the pre and post-war era, which

were replete with conceptual incongruities and

equivocations. Dorrien recounts Gilkey’s gradual

awakening to the theological gravity of these

theological and philosophical issues, especially the

notion of God’s action in human history. For

Neo-orthodoxy and its close cousin, the Biblical

Theology movement, the “mighty acts of God” recorded in

the bible served as the historical basis for

Christianity. However, Gilkey began to recognize a

serious problem with this view, viz., that it

“emphasized the historical character of biblical

religion, but it also threw history overboard whenever

it dealt with biblical events that were historically

questionable. Much of its ‘historical’ grounding was

theological, not historical in the scientific sense” (Dorrien,

1997: 143). It turned out that Neo-orthodoxy and the

Biblical Theology movement were torn between a

pre-modern orthodoxy and the exigencies of modern

historical consciousness—and, when pressed, they

ultimately opted for a fideistic account of salvation

history. Gilkey thus came to realize that Neo-orthodoxy

was not as modern as he had originally thought, and that

continuing down this theological path would entail a

sacrificium intellectus that he could not abide.

According to Dorrien, Gilkey eventually arrived at the

rather embarrassing conclusion that, “theology was

obliged to return to Schleiermacher’s starting point”

(Ibid: 153).

Perhaps a greater irony—beyond that

of wandering through the wilderness of Neo-orthodoxy

expecting to find the Promised Land, only to find

oneself circling back to the fleshpots of

Schleiermacher—was that Gilkey’s newfound liberalism was

so unconsciously indebted to Tillich that he was utterly

blinded to the extent of this influence. What Gilkey

perceived to be an innovative approach to theological

reasoning was in fact thoroughly derivative of Tillich.

Gilkey’s next major book, Naming the Whirlwind: The

Renewal of God-Language (1969), was certainly a

creative application of Tillichian thought to a new

intellectual situation (viz., the “Death of God

Theology” movement). However, its main thesis was

essentially a rehashing of Tillich’s previous insights

about the ultimate dimension of human life, and the

inevitability of aligning oneself with an ultimate

concern. In his book Gilkey on Tillich (1990),

Gilkey relates a telling conversation with Tillich in

1964, in which he shared a recent paper that would serve

as the basis for Naming the Whirlwind. After

reading the paper Tillich, rather deflated, replied,

“But Langdon, I said all this years ago.” Clearly

embarrassed, Gilkey responded somewhat sheepishly, “I

know Paulus…but in this new situation I have just

discovered what it means, and I have, therefore, only

now found myself saying it after you, but now in my own

way” (Gilkey, 1990: xiv).

Tillich never tired of calling

attention to the ambiguous nature of human life under

the conditions of existence. It is fitting then that his

own theological influence on his pupil Langdon Gilkey

was as powerful and pervasive as it was ambiguous.

Bibliography

Dorrien, Gary. The Word as True

Myth: Interpreting Modern Theology. Louisville:

Westminster John Knox Press, 1997.

Gilkey, Langdon Brown.

Catholicism Confronts Modernity: A Protestant View.

New York: Seabury Press, 1975.

_____. Creationism on Trial:

Evolution and God at Little Rock. Virginia: The

University of Virginia Press, 1998.

_____. Gilkey on Tillich.

New York: Crossroad, 1990.

_____. Maker of Heaven and

Earth: The Christian Doctrine of Creation in the Light

of Modern Knowledge. Garden City NY: Anchor

Books/Doubleday, 1959.

_____. Naming the Whirlwind: The

Renewal of God-Language. Indianapolis and New York:

The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1969.

_____. Nature, Reality, and the

Sacred. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1993.

_____. On Niebuhr: A Theological

Study. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press,

2001.

_____. Reaping the Whirlwind: A

Christian Interpretation of History. New York:

Seabury Press, 1976.

_____. Shantung Compound: The

Story of Men and Women under Pressure. New York:

Harper & Row Publishers, 1966.

Tillich, Paul. Systematic

Theology. 3 vols. Chicago: University of Chicago

Press, 1951.

The information on this page is copyright ©1994 onwards, Wesley

Wildman (basic information here), unless otherwise

noted. If you want to use text or ideas that you find here, please be careful to acknowledge this site as

your source, and remember also to credit the original author of what you use,

where that is applicable. If you have corrections or want to make comments,

please contact me at the feedback address for permission.

|