Tillich's Theological Influence on Dietrich Bonhoeffer

(1906-1945)

|

|

|

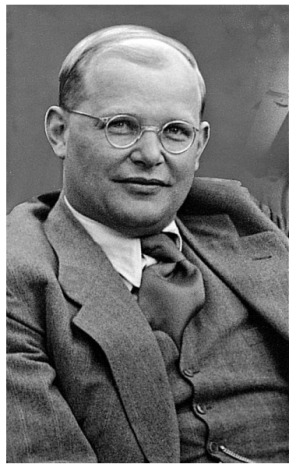

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (from

here) |

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was a theologian, administrator,

professor and pastor. Many individuals such as Barth and

Buber influenced his theology and professional life but

many do not realize that Tillich also played a

significant role in his life and thought.

Professionally as both a professor and pastor,

Tillich was influential in securing for Bonhoeffer a

ministry to refugees and a teaching position at Union

Theological Seminary in New York City. Henry Smith

Leiper and Tillich has been appointed to a committee to

find an individual to work with refugees fleeing from

Nazi persecution and newly arriving in New York city.

Tillich “stated his conviction that he [Bonhoeffer] was

exactly the right person for this delicate and difficult

task” (Works, Vol. 15: 173-174). On May 31, 1939

in a letter from Samuel McCrea Cavert, Leiper conveyed

that suggestion, urging that Dietrich Bonhoeffer be

moved to New York City to undertake the urgent work with

refugees. Reinhold Niebuhr then further suggested that,

while working with refugees, Bonhoeffer might also

lecture at Union Seminary.

Early within the development of Bonhoeffer’s thought,

he was reading and consulting the works of Paul Tillich.

Tillich’s influence upon Bonhoeffer was in the areas of

theology of revelation, and church and culture.

Bonhoeffer initially understood revelation as

dialectical in a way that was influenced by the thought

of Tillich (Vol. 2: 8). Later, in Act and Being,

Bonhoeffer argued against Tillich’s understanding of

revelation as Tillich presented it in The

Religious Situation. Bonhoeffer argued that

revelation marks a clear distinction between

philosophical and theological anthropology. Bonhoeffer

believed that revelation informs a theological

anthropology that understands human existence as

determined by guilt and grace. Philosophical

anthropology, by contrast, cannot adopt this viewpoint

on human existence but must understand existence as an

unconditional threat or the need of humanity to

understand itself (Vol. 2: 77, note 89).

In 1939, as a part of the last five pages of

American Diary, Bonhoeffer included notes that

became the foundation of his “Essay about Protestantism

in the United States of America.” Bonhoeffer wrote this

essay after his return to Germany in August of 1939.

Bonhoeffer there described a turn in American theology

over the previous ten years as a return to revelation

and away from secularism in its many forms, including

modernity, humanitarianism, and naturalism. He located

this shift from the “social gospel” to Dogmatics

especially at Union Theological Seminary and in the

writings of German theologians who were deeply

influential in America, among whom he numbered Tillich

(Vol. 5: 459).

Bonhoeffer appreciated Tillich’s early work on the

relation of religion and culture (Vol. 11: 226). In a

letter to Eberhard Bethge on June 8, 1944, Bonhoeffer

addressed the rise of modernity over the previous

century and the correlative loss of God in society, in

the academy, and in the sciences. Subsequently he

commented that only in existential questions does God

continue to be relevant because the existential

philosophers try to demonstrate the continuing need for

God in the life of the world in the aftermath of the

modernity and secularism—a relevance that liberal

theology fails to express. In commenting on Tillich’s

work in light of then current cultural crisis of the

loss of God in Christ within the world, Bonhoeffer

argued that Tillich interprets the development of the

world through the form of religion. Social leaders felt

misunderstood by Tillich and rejected his analysis. This

failure of understanding, according to Bonhoeffer, is

rooted in flaws within Tillich’s analysis, including

especially that Tillich interpreted the world against

itself and believed he understood the world better than

it understood itself (Vol. 8. Pg. 428).

In Sanctorum Communio, Bonhoeffer’s

dissertation completed in 1927, he argued against

Tillich’s understanding of the holiness of the masses.

While discussing the community of the church addressed

through word and sacrament, Bonhoeffer argued for the

community of faith made up of individuals. In

contemplating the Protestant community as an instance of

the masses, Bonhoeffer referenced Tillich’s perception

that the ‘spirit’ has withdrawn from the masses, but

that a direct relation between the masses and the

‘spirit’ is still possible. Tillich understood the

holiness of the formless mass as receiving form through

“the revelation of the forming absolute” (Vol. 1, pg.

239). Bonhoeffer responded that Tillich’s understanding

of the “holiness of the masses” has “nothing to do with

Christian Theology.” The holiness of God’s

church-community is bound to God’s word in Christ, that

word is only ever personally appropriated, and never a

decision of the masses. Bonhoeffer agreed with Tillich

that the church-community must be engaged with and it

must respond when the masses are seeking community. Yet

the relevant criteria for judgment derive from the

church-community's judgment of the masses, not the

masses' judgment of the church-community (Vol. 1, pgs.

239-240).

Later in Sanctorum Communio, Bonhoeffer picked

this theme up again. He points out that this revelation

of God in the word of Christ is not known in the masses.

God’s concrete historical will is known by the masses

but only as God’s word of judgment toward the masses.

Salvation is only within the church (Vol 1, pgs.

273-274). In his lectures on the History of

Twentieth-Century Systematic Theology, Bonhoeffer

agreed with Tillich that humanity is a new form of life

in nature, expressing community and enabling the

rediscovery of the transcendent in the past act of God

in Christ. God is manifest in Christ within history and

this becomes the basis for the new life of the

individual and community—a thoroughly Tillichian theme

from the Systematic Theology, especially volume 3

(Vol. 11, pg. 228).

In conclusion, while much disagreement exists between

the theology of Bonhoeffer and Tillich, Bonhoeffer’s

recognition of the dialectic aspect of the nature of

revelation is partly the result of Tillich’s influence.

Bonhoeffer recognized the significant influence of

Tillich in the then current theological and cultural

shift from secularism to the rediscovery of revelation.

The emphasis of Bonhoeffer on revelation in his own

theology is a result of Tillich’s thought that enacted

change within the discipline. Finally, while they

disagreed over much concerning a theology of church and

culture, they agreed that the community of the church

needs to provide community for all individuals.

In response to the suspension of Tillich from his

teaching position at Berlin University, several students

were collecting signatures urging officials of the

Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs to

reconsider. Subsequently those officials asked for a

letter from the Berlin faculty concerning the

theological significance of Tillich. Bonhoeffer wrote to

Erich Seeberg on April 21st, 1933 to inquire about his

initiating a process of support for Tillich. Bonhoeffer

wrote, “Even just my own personal gratitude for what I

have learned from Tillich on many occasions gives me the

courage to turn to you, and ask if you might initiate

such a process among the faculty” (Vol. 12, pg. 104). In

his own words, Bonhoeffer recognized the profound impact

that Paul Tillich has had on his life and thought.

Bibliography

Barnett, Victoria J.; Barbara Wojhoski (eds).

Dietrich Bonhoeffer Works. 16 vols. Minneapolis:

Fortress Press, 1986-present.

The information on this page is copyright ©1994 onwards, Wesley

Wildman (basic information here), unless otherwise

noted. If you want to use text or ideas that you find here, please be careful to acknowledge this site as

your source, and remember also to credit the original author of what you use,

where that is applicable. If you have corrections or want to make comments,

please contact me at the feedback address for permission.

|