|

Dreyer

shows us that the world of objects, places, and events is not the real

world. The real world is inward. All there is is soul, soul, and more

soul. Dreyer

shows us that the world of objects, places, and events is not the real

world. The real world is inward. All there is is soul, soul, and more

soul.

* * *

Our inner storms of feeling

are the only important weather. The wars that matter are all within.

* * *

The problem that confronts

every artist is how to get the inside of life into the work, when all

that can be seen, all that can be shown, is the outside.

* * *

A poet or novelist can describe

a character's thoughts and feelings. But painting and photography are

limited to the realm of the visible. How do you photograph or paint the

soul? How do you transform surfaces into depths? How do you represent

the invisible in terms of the visible?

* * *

The eyes are a doorway. We

plunge head first into Anne's flickering flames and Joan's limpid pools–so

transparent, permeable, liquid, inviting.

* * *

Has anyone ever been more exposed

on film than Joan? Has anyone ever been more vulnerably displayed to the

rude gaze of strangers?

* * *

We have a superficial definition

of nakedness. You remove your clothes and bare your flesh. Joan, Anne,

Inger, or Gertrud show us more than skin. They peel back their bodies

and bare their souls.

* * *

No one could be more naked

than Joan. Her face is the most naked thing ever photographed.

* * *

We look at her, but more important,

she looks at us. We must prove ourselves worthy of returning her gaze.

We are the ones really on trial, not her.

* * *

Like a virgin lover, she tests

our worthiness to receive her. By throwing herself on our mercy, she makes

the greatest possible emotional demand. By asking nothing, she asks everything.

By making no appeal, she makes the supreme appeal.

* * *

She is not embarrassed by our

look; it is we who are embarrassed by hers. We feel ashamed because we

know we can never deserve this degree of trust. She is innocent; we are

the guilty ones.

* * *

As when a newborn baby looks

up at us, we wonder how can we ever live up to the infinity of this faith

in us? How can we ever reciprocate the absoluteness of the love she so

totally gives?

* * *

If we would see her as she

really is, we must look at her the same way she looks at us: Tenderly,

purely, chastely. In awe and wonder. In humility. With love.

* * *

The men around Joan don't know

how to look at her. The law of the universe is that you get what you are.

They see only what they are capable of seeing. They see only their own

polluted hearts.

* * *

In their gaze, her nakedness

is pornography. In their hearts, her exposure is obscenity. Her actions

are immorality.

* * *

But the answering law of the

universe is that true purity can't be polluted. Joan is immune to their

sneers, their leering depravity. Nothing about her will ever be made obscene

or dirty or guilty.

* * *

To the pure all things are

pure. To the eyes of the spirit, everything is spirit. Their looks only

puzzle her. She stands forever beyond them, free of them, unreachable

by them.

* * *

The voice is another way in:

Inger's terrible birth-gasps in Ordet, Arne and Marianne's agitated

pants in Two People, Anne's playful giggle and Herlofs Marte's

anguished cries in Day of Wrath, Gabriel's discouraged sighs in

Gertrud.

* * *

Truth is never spoken. Words

are always evasions. We don't say what is really on our minds. Real speech

is silent.

* * *

The sound of the breath speaks

truer than the words uttered. It's not what we say, but how. Words are

from the brain; the breath is the voice of the heart.

* * *

Gestures, glances, movements,

pauses speak better than words ever can. The body speaks more than the

mind can know.

* * *

At this level of purity and

intensity, there is no need for artistic heightening or rhetoric. Dreyer

pares away all of the extras because he knows that they only distract

us. Simple situations, simple costumes, simple gestures, the most ordinary

events say it all. The way old man Borgen walks and sits in Ordet

speak more eloquently than fancy lighting or dialogue ever could.

* * *

As Dreyer once said: The great

dramas are played quietly. We may be still as an ice mountain on the outside,

but raging like a blast furnace within.

* * *

It is not accidental that women,

mistresses of inner space, are at the center of these works, and men,

manipulators of outer realms, are on the outside, in the dark. It takes

a woman to teach them to look inward, so that they can see anything.

* * *

To reach the spiritual realm,

each art must push against its natural tendencies. Film, the art of motion,

must have its movements arrested. Painting, the art of stillness, must

find a way to capture the movements of the soul.

* * *

Our art is too propulsive,

too fast, too obsessed with getting somewhere. Most films, videos, and

paintings are devoted to quick knowledge. They encourage us to take the

world in with glances. You read meanings with a look. Dreyer goes in the

other direction. He slows down events and actions almost to the point

of cessation. He makes knowing gradual. Like Tarkovsky's, his time is

slow and deep.

* * *

He knows that the soul is shy.

It must be wooed. It shows itself only to the patient. It defies rapid

knowing. It asks us to live with it, if we would know it.

* * *

Shallow works of art, like

shallow people, yield up their meanings in a minute, but you must spend

time with the deep ones. The characters and events in these works must

be lived into. To know them, even a little, you must return to them over

and over, exploring their secrets, giving yourself to them in time.

* * *

No shortcuts are allowed. These

experiences accumulate meaning in time.

* * *

If you would plumb its spiritual

depths, you must suffer though every second of Joan's trial. You must

live through the ups and downs of Inger's hopes and dreams. You must live

with Gertrud for a long time before you can even begin to understand her.

These experiences do not open themselves to strangers. You must prove

yourself ready to receive them.

* * *

And even then, after we have

watched and prayed with them, after hours have gone by, how far away from

us these figures still remain. The distance never disappears.

* * *

Has any artist made us more

aware of the interstellar distances that separate even lovers? Or what

an effort it takes to bridge the gaps between us even for a second?

* * *

The spirit is shrouded in solitude.

Cosmic vacuums of inner space sheathe our souls. The nucleus of the atom

is not more isolated than Gertrud, Joan, or Anne.

* * *

The close-ups draw us in, but

also hold us outside. We can't quite penetrate the veil. We can't reach

through the mask.

* * *

We can't see in these depths.

We swim in darkness blacker than the bottom of the ocean. The deeper we

dive, the deeper the mystery.

* * *

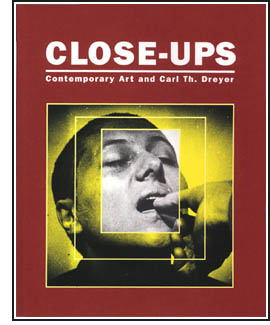

Dreyer's close-ups bring us

close, closer, closest. He couldn't get too close. He would have taken

the camera inside if it were possible.

* * *

In The Passion of Joan of

Arc space is compressed by the closeness of the shots. The third dimension

disappears. But what is lost as physical background is gained as emotional

foreground. The more the space behind Joan is flattened, the more the

space in front of her leaps out–but not as space but spirit.

* * *

When we get this close, faces

no longer look like faces. Fragmented, broken, cut into pieces, seen from

odd angles, bodies become abstract lines, shapes, forms. But, as in cubism,

the less recognizable the form is, the more spiritual it becomes. The

bits of skin become translucent. The soul shines though the seams and

cracks.

* * *

The abstraction on screen moves

us to an answering state of abstraction in our viewing. Where shape cannot

be read as shape, it is felt as spirit.

* * *

The flesh is burned away. It

peels, breaks, and cracks as the soul leaps free of it. Baptism by fire

is the birth of the spirit. Pain, loss, and relinquishment are the paths

to knowledge.

* * *

Only when we give ourselves

away, can we discover what we really are. Only when we let go of all of

our proud accomplishments, do we make ourselves infinite. Only when we

die to the world are we born to the spirit.

* * *

We want comfort and rest, but

Dreyer shows us that the soul is forever in flux and transformation. Objects,

places, people stand still, but the spirit endlessly heaves and surges.

The breath moves in and out. The spirit coruscates and flickers. The heart

expands and contracts. Though we want calm, these pulsebeats are the essence

of life. To stop moving and changing would be to die.

* * *

The products of the mind freeze,

but the heart melts them. The soul eternally flows.

* * *

While spirit flowed from every

pore of the world in the beginning, in our time it is forced to cower

in dark corners. We shove it off into out of the way places: into the

church, into cults, into death and funerals, into frenzies of horror and

fear. Dreyer restores it to its place at the center of everyday life.

The soul is in the farmhouse, the drawing room, the bedroom.

* * *

His spirituality is not otherworldly,

not separate from ordinary life, but mixed into the everyday. Johannes

thinks spirituality is to be with God in heaven; Inger and Maren know

better. It is in milking the cows, scrubbing the floor, and doing the

washing.

* * *

The blendings of the natural

and supernatural in Dreyer's work are not to convince us of the existence

of a special realm of the supernatural, but to show us that there is no

difference between the two realms. What exorcism dealt with in the middle

ages, and witchcraft expressed in the seventeenth century, the soul is

to every time and place.

* * *

Soul threatens all established

values because it obeys no worldly master and yields to no material bribes.

All saints are heretics. All lovers are dangerous.

* * *

Society is the mortal enemy

of soul, which it can neither control nor understand. It hates and fears

spirit because spirit reveals the irrelevance of all of the things it

values and esteems.

* * *

It is a fiction of our fallen

time that the body and the soul are different. Dreyer shows us that it

is only in a non-spiritual world that the spirit is separated from the

flesh. As the final kiss in Ordet shows, true love is soul and

saliva mixed to the point that they cannot be told apart.

* * *

Only when we despair do we

feel there is a difference between spiritual and physical love. In our

exalted moments, we realize that sex and spirituality are the same.

* * *

Many of these truths are hidden

and unspoken and must remain so. They cannot be given; they must be found

out by each individual for himself. We must earn them. Otherwise they

are merely words. But as experiences, they are always within us, near

at hand, instantly available to anyone in need.

* * *

God made the soul invisible

for a reason. It is preserved from being handled by the unworthy. It is

veiled in mystery to protect it. And to protect the unready from it. The

truth would blind them.

* * *

In the end, Dreyer's work reminds

us that although the world denies spirit, art can revive our faith in

it. When we lose our spiritual way, art can map the path back. It wakes

our souls from slumber. It exists to speak a language beyond any worldly

one–the language of the soul.

This page only

contains excerpts and selected passages from Ray Carney's writing on Dreyer.

To obtain the

entire essay from which this discussion is excerpted as well as a book

devoted to Dreyer's films, click

here.

|