In

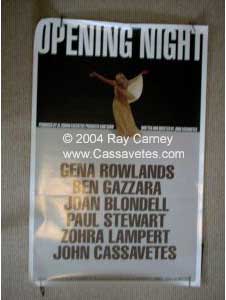

Opening night, Myrtle Gordon, a talented middle aged

stage actress, spirals into a crises of confidence in her ability

to act or relate to others when an adoring fan dies on the opening

night of her latest play. Her plight is complicated by her life

as an actor surrounded by other actors for whom the difference

between real emotion and performance is often blurred. 1978

(144 m. Color) Stars Gena Rowlands, John Cassavetes, and Ben

Gazzara In

Opening night, Myrtle Gordon, a talented middle aged

stage actress, spirals into a crises of confidence in her ability

to act or relate to others when an adoring fan dies on the opening

night of her latest play. Her plight is complicated by her life

as an actor surrounded by other actors for whom the difference

between real emotion and performance is often blurred. 1978

(144 m. Color) Stars Gena Rowlands, John Cassavetes, and Ben

Gazzara |

REVIEWS

Merci John et Gena pour

ce film magnifique - Tourney

Opening Night. Just a note that for anyone who wants important background

information about Opening Night and how it was made, I highly recommend

Ray Carney's Cassavetes on Cassavetes book, which is available on

Amazon.com at a great price. Carney has amazing behind-the-scenes

information about how Cassavetes created all of his no-budget wonders

completely outside the system.

Carney knew Cassavetes and had a series of conversations with him

before his death about his philosophy of life and art. Carney

also has a terrific web site with writing on Cassavetes and other

indie filmmakers. Great movie and great supporting info. Both

well worth owning. Buy the book and the DVD. You'll be consulting

both many many times in the future for wisdom about life and

art.

American

film portraits of the aging actress are not characterized by their

depth or generousity of spirit, from the high camp bitchines of All

About Eve to the creepy misogyny of Sunset Boulevard,she

has most often been perceived as both pitiable and dangerous, reflecting,

perhaps, societal attitudes about aging women in general. In Opening

Night, Cassavetes employs his ferocious sympathy in creating a

character who refuses to conform to the definitions of others in her

quest for the identity of, and her fight for the survival of, The

Second Woman, the title of the play she is starring in. Battling

he co-star (played with brilliant understatement by John Cassavetes)

the director,the writer, and most of all, the younger self, personified

by the ghost of a young fan who is killed. Myrtle refuses to play

her part as written because the play doesn't have "Hope". When the

writer, in one of Joan Blondell's last and best performances, tells

her that if she "says the lines with a certain amount of feeling"

the character will emerge, Myrtle rejects this facile solution in

favor of her continued struggle for personal authenticity. All of

Cassavetes characters are concerned with just this struggle, and like

his earlier films, Opening Night explores the insterstices

between the embattled self and others, the parallels between performance

and life, and the triumph of go-for-broke-craziness over formulaic

rationality. This is my favorite Cassavetes film, and also arguably

his most difficult. - Yuri Hospodar American

film portraits of the aging actress are not characterized by their

depth or generousity of spirit, from the high camp bitchines of All

About Eve to the creepy misogyny of Sunset Boulevard,she

has most often been perceived as both pitiable and dangerous, reflecting,

perhaps, societal attitudes about aging women in general. In Opening

Night, Cassavetes employs his ferocious sympathy in creating a

character who refuses to conform to the definitions of others in her

quest for the identity of, and her fight for the survival of, The

Second Woman, the title of the play she is starring in. Battling

he co-star (played with brilliant understatement by John Cassavetes)

the director,the writer, and most of all, the younger self, personified

by the ghost of a young fan who is killed. Myrtle refuses to play

her part as written because the play doesn't have "Hope". When the

writer, in one of Joan Blondell's last and best performances, tells

her that if she "says the lines with a certain amount of feeling"

the character will emerge, Myrtle rejects this facile solution in

favor of her continued struggle for personal authenticity. All of

Cassavetes characters are concerned with just this struggle, and like

his earlier films, Opening Night explores the insterstices

between the embattled self and others, the parallels between performance

and life, and the triumph of go-for-broke-craziness over formulaic

rationality. This is my favorite Cassavetes film, and also arguably

his most difficult. - Yuri Hospodar

Hello I’m a kid from Tenerife,

Canary Islands, Spain. I like Cassavetes films very much, buy i only

had seen three of them. Opening night is one of those films I watched

it on spanish TV same years ago. I remenber i like it very much but,

in some ocasions, the stranges cameras movemente confuse me. I think

is a film about self destruccion and i still don’t know how a drunk

woman can act so well without not faint. Anyway, Geena Rowlands is

wonderful on that film, and Cassavetes (he looked exactly as Bogart)

and Gazzara. I love Cassavetes and hope i can watch more of his movies.

Thanks for the opportunity and excuse me, for my english is not good.

Julio Herrera

Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain

As

a subtitler, this was probably the film that excited me most to work

on. Such an experience is not work - it’s a pleasure. As

a subtitler, this was probably the film that excited me most to work

on. Such an experience is not work - it’s a pleasure.

Bernardo - Portugal

Opening Night is

a beautiful, moving film. The acting, directing and writing is brilliant.

The experience of watching such a film takes my breath a way. The

way that Myrtle's imagination and self-doubts are blended into both

the play and the film is wonderful. Gena Rowlands is once again at

her best and the cast work wonderful together. I could never have

a favorite Cassavetes film beause each one is such a different and

unique experience in itself but this is definately one of my favorites.

Opening Night is

one of the most profound films I have ever seen. Gena Rowlands' performance

is beautiful. Her struggle, her despair, her moments of "hope" set

against her pain and her doubt are umforgettable. Watching this movie

gives one the same feeling as reading a novel that somehow manages

to allow everything but the experience to drop away. It is a modern,

brilliant, moving and most of all authentic look at a beautiful and

talented, woman's need to "know." It should be required viewing for

every studio exec who is rushing to make the next Adam Sandler or

"teen romance" or mindless action movie. Perhaps just perhaps they

will be moved enough to remember just how amazing and life-changing

a brilliant movie can be.

Great movie, last scene

(the end of the play) simply devastating.

Playing with Performance:

Directorial and Performance Style in John Cassavetes’s Opening

Night

by Maria Viera

Two

elements are always in play when dealing with John Cassavetes’s

work: the impression of improvisation, although we know his films

are not improvised, and his “anti-filmic” technical elements, that

do not “construct” a performance on the screen, but allow for one

to take place before the camera. Cassevetes prefers that the filmic

tools used to construct a performance in a given scene, such as

camera angles, lighting, and camera movement, be used sparingly,

only when necessary, with the performance always given top priority.

It is not just a question of a long-take style that “records” a

performance--Cassavetes does edit, although he rejects conventions

such as the shot-reverse-shot regime--but that he views film technology

as something he tries to keep out of the way of the performance.

Thus, the distinguishable performance style in his films emerges

in the dynamic between his script, his shooting and editing style,

and his work with his actors.

Cassavetes

is considered to be one of the few, major independent American directors

able to work outside the Hollywood system. Although he directed several

films with traditional studio funding, the money he made as an actor

allowed him to make eight films that were solely under his control.1

His rejection of Hollywood and the “realism” it offered fits into

the more modernist trajectory of Italian neorealism--with which

he was familiar and with which he was impressed--and the European

art film.2 Cassavetes’s films were always much more

appreciated in Europe. Simultaneously, Cassavetes shares certain

modernist characteristics with the French New Wave directors--self-reflexivity,

for example. However, unlike Jean-Luc Godard’s ideologically motivated

intervention, Cassavetes took on the task of exposing Hollywood production processes in order to

get to the characters, their situations, and the kind of performance

style that personally interested him. Cassavetes wanted to make

art.

Throughout

his career, Cassavetes always emphasized that his films were not

made to be easily understood. As in the modernist tradition, he

created a body of work that requires an active spectator working

through innovative, complex, and original material. To use Bertolt

Brecht’s neologism, Cassavetes was not interested in “culinary”

drama. Cassavetes concurred with Robert Altman’s statement: “I

don’t know how to make a film for 14 -year-olds” (Gritten 73).

At

the same time, Cassavetes’s work, with its radical departure from

more pictorially oriented styles, comes out of a strong artistic

sensibility that aligns itself with naturalism. Although his characters

are quirky and often on the edge, if not “under the influence,”

they come from everyday life. They live in specific social environments

and their actions are a consequence of personal history and environmental

forces. As with other tendencies associated with naturalism, Cassavetes’s

characters, as performed by his actors, often cannot express or

even understand the situation in which they find themselves. Like

real people, they improvise as they go. 3

Often

shooting in his own house over a long period of time, Cassavetes

created a working environment of which Konstantin Stanislavsky would

have approved. Stanislavsky insisted that at the Moscow Art Theater, where he directed, the set and lighting

should be used for their effects on the actors rather than for impressing

audiences. Likewise, Cassavetes was not distracted by concerns

with how the film looked pictorially or with elaborate set or lighting

design. His focus, as that of the tradition of naturalism, was

the characters and how they might behave in the situations in which

he placed them.

At

first glance, Opening Night (1977), may seem a strange

choice to use to exemplify and illustrate Cassavetes’s naturalistic

tendencies and to use as an example of how he is part of a re-emerging

naturalism in mid-Twentieth Century cinema. The reason is that

there are two very “non-realistic” elements in Opening Night

that are major deviations from the usual Cassavetes’s style.

After

the prologue of the play in tryout in New Haven, the title sequence

shows the main character, Myrtle Gordon (or is the actress Gena

Rowlands?) from behind, in a flowing evening gown with large sleeves

of pleated nylon producing a wing-like effect, superimposed over

an applauding audience. It is a visual metaphor for Myrtle’s (and

by implication, all actors’) most basic desire: to be loved. The

second “non-realistic” element is the “vision” of Nancy (the ghost,

the other woman, the younger Myrtle) whom we actually see in shots

with Myrtle, although none of the other characters see her. A ghost

is not a standard element in naturalism. However, Cassavetes did

not intend the “ghost” to be taken as a possible apparition. He

said: “This is a figment of her [Myrtle’s] imagination, it’s not

a fantasy, it’s something that’s controllable by her” (Carney, Cassavetes

on Cassavetes 410).

In

other ways though, Opening Night is the film par excellence

to use to discuss Cassavetes’s naturalistic tendencies because it

is a film about theatricality, about acting, about “putting on a

performance,” both literally and figuratively. As Raymond Williams

explains: “In high naturalism the lives of the characters have soaked

into their environment... moreover, the environment has soaked into

the lives” (Innes 5). Opening Night is a film about a play

with players who are playing with their performances in life, as

well as on the stage.

SCRIPTING

Ray Carney’s excavatory work in his book, Cassavetes

on Cassavetes,4 outlines the determinants at play

in the genesis of the Opening Night script: Cassavetes’s

continued interest in doing a “backstage drama” because of his admiration

for All About Eve and through discussions with Barbara Streisand

about possibly directing A Star is Born; his interest in

material from his and Rowlands’s lives especially in terms of what

their lives would have been like if they had never met (she, like

Myrtle, devoting her life to the theatre without marriage or family;

he, perhaps, the cynical, but charming user, Maurice); plus both

Cassavetes and Rowlands were now in their late forties and although

he had dealt with the theme of woman and aging in earlier films,

this theme had become more immediate. Cassavetes said the script

for Opening Night began with the idea of exploring “people’s

reactions when they start getting old; how to win when you’re not

as desirable as you were, when you don’t have as much confidence

in yourself, in your capacities” (Carney, Cassavetes on Cassavetes

409).

In

developing the script, Cassavetes followed a naturalistic stratagem--

the “scientific observation” of external physical existence--looking

at people in their environment. According to Carney, Cassavetes

did his “research” by speaking with Sam Shaw’s wife on the phone

almost every night for a year. He spent time with Rowlands, her

mother, and his mother absorbing their conversations. Cassavetes’s

working method was to become his characters as he wrote his script.

Carney reveals through an interview with Bo Harwood, that Cassavetes

became his characters while creating them. He would “come into

the office ‘as Myrtle’--trying out her lines for the script, doing

her tones, experimenting with gestures to see what they felt like”

(Carney, Cassavetes on Cassavetes 408). Cassavetes said:

“You can’t do this kind of exploration through film techniques.

You have to write and write and write. Without writing, I don’t

think that filmmakers could do as well because techniques--well,

you’ve seen all of them!” (Carney, Cassavetes on Cassavetes

408).

The

second driving force Cassavetes identified as part of the ideation

of Opening Night is “to show the life of an artist, of a

creator” (Carney, Cassavetes on Cassavetes 409). Cassavetes’s

characters are “theater people” in their specialized environment--a

theater company putting on a play. Cassavetes’s many years in the

theatrical environment provided endless material from which to create

his script. 5

Cassavetes

extends the idea of theatricality beyond those who work in the theater.

He explains a further theme of his film: “So, Opening Night

was about the sense of theatricality in all of us and how it can

take us over, how we can appear to be totally wrong on some little

point, and never know what little point we’re going to fight for”

(Carney, Cassavetes on Cassavetes 415).

The

script of Opening Night exhibits a defining aspect of naturalism--the

primacy of character, characters in a situation, characters in a

specific environment. The film is not plotted in the conventional

sense. It does not follow a three-act structure with mandatory

plot points. There is barely a climax in the Aristotelian sense.

Myrtle does arrive just in time to the opening night performance

with the rest of the company thinking they will have to cancel the

show. She is drunk and struggles to make her way through the scenes.

However, it is unclear why she got drunk in the first place. Cassavetes

explains: “In the end, she doesn’t even get anything. She only

gets what makes her happy” (Carney, Cassavetes on Cassavetes

413).

Cassavetes

purposely works against classical Hollywood narrative structure. He says: “Now, all my leanings are anti-plot

point. I hate plot point! I don’t like focusing on plot

because I think the audiences don’t consist of only thirteen-year-old

kids and also that each person you see in life has more to them

than would meet the eye” (Carney, Cassavetes on Cassavetes

419).

The

scenes in Opening Night can almost be seen as a series of

“improv exercises,” not in the sense that the actors are improvising

the dialogue, but in that Cassavetes, as screenwriter, works by

structuring the script into a series of “improv situations.” Improvisations

used, for example, in acting classes are structured by putting a

character into a specific situation or environment to explore how

that character will react.

For

example, two actors are assigned the parts of an older husband with

a younger wife. They are told:

A husband and

wife are having an intimate conversation (plus drinking) at 4:30 in the morning. He is a theater

director. She is his younger, totally dependent, stay-at-home wife.

The phone rings and it is his leading actress desperately in need

of reassurance. He must declare his love and admiration to her

while being sensitive to his wife’s presence. His wife tries to

playfully distract him from the conversation but she knows his livelihood,

as well as hers, depends on his ability to deal with the actress.

A

second example: two actors are assigned the part of parents grieving

the loss of their 17-year-old daughter; a third is an actress who

visits their home.

The actors are

instructed:

The actress arrives

at the home of a young girl who was hit by a car and killed. The

actress is not invited but wants to express her condolences. The

family knows that it was she the young girl was trying to see when

the car struck her. The parents reject the actress and want her

to leave.

These

are, of course, examples of “character in situation” from Opening

Night, but they could just as easily be improvisation exercises

in an acting class. The idea in the acting exercise would be to

see how that character would react in that given situation.

In

the scripting process, Cassavestes seems to have developed his characters

as he placed them in environments that would help explicate his

themes, themes which are based on “character in situation,” not

action. Cassavetes himself struggled with the complexity of the

human condition--in fact, he seems to have taken great pleasure

in exploring the struggle and finding a way to portray that daily

life and the concerns we all share. He seems to have worked from

the premise that the situations, problems, and issues with which

he struggled were of interest to all of us because of the humanity

we share.

Cassavetes’s

films are never reducible to one theme--to what Stanislavsky terms

the spine of the play--nor are his characters reducible to one character

spine, one goal or desire for each character that moves the action

forward. Instead, Opening Night works through a complex

problematic of related themes. For example, the film explores

the various ways to be loved. Myrtle is loved by the public. Myrtle

is loved (often falsely) by the theatrical company. The film also

deals with the nature of physical love with the question of how

can one be loved when one no longer possesses sexual appeal. How

can an older career woman without children and without a husband

be loved? Both Maurice and Marty tell her she “doesn’t turn them

on anymore.” This theme is picked up by Maurice, David, and Manny

who at various times throughout the film all mention that affairs

with young women don’t work anymore.

Directing

What

is unique to John Cassavetes’s directing style is his rejection

of standard Hollywood filmmaking techniques and procedures

in order to free his actors from the constraints which, he, as a

professional television and film actor, felt worked against the

type of performance style which interested him. The combination

of his shooting methods and his screenwriting lead to a performance

style that is not only consistent among his various actors, but

is the defining characteristic of a Cassavetes’s film.

Opening

Night was shot over a five-month period from November 1976,

to March 1977, and completely financed by Cassavetes himself. He

had to take time off in February for an acting job in a TV pilot

to make money to complete the film. He used three main locations:

the Lindy Opera House, the Pasadena Civic Auditorium, and the Green

Hotel. He believed in shooting on location for artistic reasons,

but he also could not afford to build sets in a studio for the films

he financed himself. The three main locations for Opening Night

were quite extravagant compared to locations used in his earlier

self-financed films. He did shoot the seance scene in Opening

Night in his own home, which he had used in earlier films such

as A Woman Under the Influence. Opening Night was

a much larger production with a larger budget (about $1.5 million)

than that of his previously self-financed films (Carney, Cassavetes

on Cassavetes 413-416). Perhaps reflecting the budget, it has

higher production values than his earlier films and more sophisticated

camera work in many scenes. Cassavetes does, however, continue

to use the hand-held camera in various scenes, such as the one

between Myrtle and Melva Drake, the psychic, in which Myrtle “kills”

her vision of the young girl.

The

working methods for directing actors Cassavetes developed over his

years of filmmaking were unorthodox compared to those of most mainstream

directors. He purposely kept his interpretation of the script

from the actors. He refused to dictate line readings. He felt

that if the actors were given a complete interpretation of the entire

narrative in advance it might “simplify” their performance (Carney,

Cassavetes on Cassavetes 424). Joan Blondell said that

Cassavetes did not tell her what her character’s reaction to the

final Maurice-Myrtle improvisation on the stage was to be. She

was left to work it out herself (Carney, Cassavetes on Cassavetes

424). The ambiguity at the end of Opening Night is so strong

that, as Carney points out, even Rowlands and Cassavetes did not

concur about whether the final play-within-a-play showed Myrtle’s

defeat or victory (Carney, Cassavetes on Cassavetes 424).

Cassavetes

shot a tremendous amount of footage to capture his unorthodox and

complex performances--such as those small subtle moments that sweep

for a split second over Rowlands’s face as she moves from subtext

to subtext. He shot much more coverage than those working with

him thought necessary. This would, of course, afford him the possibility

of re-scripting and re-working the film during post-production,

which he did extensively (Carney, Cassavetes on Cassavetes

421).

Cassavetes

thus aligns himself with other unconventional directors who use

directing methods designed to keep actors off-balance in order

to produce fresh, off-beat performances and avoid over-rehearsed

or “canned” scenes. Cassavetes used shooting methods that he,

among other directors such as Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich,

have found work to keep a performance edgy and unpredictable. He

did not approach directing by working to “perfect” line readings.

He sometimes kept the camera running between takes, shooting several

takes one after another, a procedure that puts pressure on the actor,

a sort of driving force which keeps him or her insecure and off-balance.

He introduced last-minute changes, either in dialogue or in action,

from that which was rehearsed. In a two-person dialogue scene,

he would give instructions or line changes to one of the actors

without telling the other (Carney, Cassavetes on Cassavetes

418-424, 436). All these methods helped him to capture a more

spontaneous, un-rehearsed quality in the performances which increased

the sense of naturalism found in his films.

Performance

Style

In

the script for Opening Night, Cassavetes has written highly

individualized characters who become completely realized people

through his directing. They will also be “modern characters” as

Strindberg defined them in his preface to Miss Julie (Jacobus

762-3). They will exhibit the “ambiguity of motive” that Strindberg

describes. It was Stanislavsky who discovered the methods for both

actor training and working on performance that provided the acting

style which fit these “modern characters.” Cassavetes shares the

premises of the Stanislavsky method: to play truthfully; to create

the life of a human soul; to live your part internally, and then

to give that experience an external embodiment. He shares many

of the objectives Stanislavsky lays out in An Actor Prepares:

“An actor must learn to recognize quality, to avoid the useless,

and to choose essentially right objectives.” These objectives should,

for example, “be real, live and human, not dead, conventional or

theatrical” (Innes 57). Stanislavsky’s methods were adapted to

various American schools of acting such as the Group Theater and

Lee Strasberg’s Actor’s Studio and eventually had a major impact

on film acting.

Stanislavsky

lays out his explanation of the super-objective (the “through line”

of action) explaining that “all the minor lines are headed toward

the same goal and fuse into one main current” ( 261). He then explains

what happens when the actor has not established his ultimate purpose

and illustrates what the line looks like if the smaller lines lead

in various directions. “If all the minor objectives in a part are

aimed in different directions it is, of course, impossible to form

a solid, unbroken line. Consequently the action is fragmentary,

uncoordinated, unrelated to any whole” (261). This seems an uncannily

accurate description of a Cassavetes actor playing a Cassavetes

character.

Cassavetes

gets his style of performance from his actors by creating double,

and sometimes triple, subtexts played out simultaneously. In theatrical

practice, the term subtext is used for what is not being said, what

lies under the dialogue. As Robert Benedetti explains: “when there

is an obstacle to direct action, the character may choose an indirect

action; we call these hidden intentions subtext” (152).

For example, there are many variations on a line reading depending

on which subtext the actor is working. One of the goals in rehearsal

is to find the subtext that best works for the scene. The character

may hide the subtext beneath the dialogue either for external or

internal reasons and the character may be either conscious or unconscious

of the subtext. The actor is not supposed to play the subtext,

i.e. the audience should not be aware of it, but, rather, be able

to deduce it (Benedetti 149). Stanislavsky says: “The whole stream

of individual, minor objectives, all the imaginative thoughts, feelings,

and actions of an actor, should converge to carry out the super-objective

of the plot” (256). Standard stage and screen acting practice is

for the actor to play one specific subtext at a time in order to

achieve the clarity of intention that Stanislavsky proposes.

Cassavetes

does not seek this clarity of intention either through his dialogue

or through the performances he elicits from his actors. The basic

actions and reactions of his characters come from multiple and often

divergent subtexts that play out simultaneously.

For

example, early on in Opening Night, Myrtle leaves the theater

and is mobbed by fans. A young woman in particular pursues her

and runs alongside the limousine as it takes the theater group to

a restaurant. The young woman is hit by another car. Myrtle is

upset and has the limo stop at her hotel. Maurice escorts her up

to her apartment as the others wait in the limo. She is rattled

and fixes herself a drink.

Myrtle: Don’t

be distant, Maurice. Come on and have a drink.

Maurice: I’m

hungry. There are people waiting downstairs in the car.

Myrtle: What’s

the matter with us? We lose sight of everything. There’s a girl

killed tonight. All we can think about is dinner.

Maurice: I gotta

go.

Myrtle walks

over to him and--in a way that suggests past intimacies and present

passion--kisses him. Maurice pulls back.

Maurice: (shaking

his head no) You’re not a woman to me anymore. You’re a professional.

You don’t care about anything. You don’t care about personal relationships,

love, sex, affection.

Myrtle: Okay.

Maurice: I have

a small part. It’s unsympathetic. The audience doesn’t like me.

I can’t afford to be in love with you.

Myrtle: Good

night.

Maurice: Yeah,

good night.

He leaves. Myrtle

pours herself a drink and with a cigarette jutting out of her mouth

walks with what is presumably her script into the bedroom. She

almost breaks into tears for a moment.

Myrtle’s character

spine for this scene is to get away from the others, to sort out

her feelings about the girl hit by the car, and to test her ability,

as presumably she has in the past, to seduce Maurice. Her double

subtext is to get Maurice to want her so as to ease the pain of

the death of the young girl and to test her sexual powers to see

if she can still seduce Maurice--two very complex subtexts to be

performed at the same time. When he doesn’t respond, she gives

up with a meek “okay,” but with a double subtext: I want to save

face and I just wanted to try, but she really does not care much

anyway. A superficial reading of the scene would be to see Myrtle

as an eccentric (or crazy) woman “under the influence” because her

behavior is so erratic and strange. If her intentions were diagrammed

as per Stanislavsky’s through line, the small lines making up the

super-objective would be leading in varying directions. It is not

simply the case of a character with internal contradictions or a

character who is undecided. Rowlands’s creation of Myrtle comes

out of the difficult, complex, and varying subtexts that she must

play at the same time. As with the character, Rowlands may not

be aware of them all, but the performance approved by Cassavetes

as director contains them.

All

of the main players in Opening Night have to deal with this

multiplicity of subtexts. The performances in the following two-person

scene reveal the highly complex subtextual work going on.6

This scene follows closely after the preceding scene between Myrtle

and Maurice and is, in a way, even more complex and enigmatic than

their scene.

Manny and Dorothy

are together in their hotel room. It’s 4:30 in the morning.

Manny: I need

your help...[unintelligible]... But I’m going to go crazy if you

don’t tell me what it’s like to be alone as a woman. What do you

do? Okay, that’s it. Will you make me another drink, please?

Dorothy: Sure.

Manny: I’m

going to get drunk.

Dorothy: Ah...

Manny: Eh,

if you want to get hostile, you go ahead. My goddamn life depends

on this play. And you should go to all the rehearsals. You should

watch everything. You should sit with Myrtle. Fill her in on yourself

and be part of it.

Dorothy: Do I

get paid for this?

Manny: If you

understudy, I’ll pay you.

The irony of

the word “understudy“ sinks in. Dorothy fools around as if she

is considering the offer. They laugh.

Manny: That’s

right. ‘Cause, I tell you, my life is getting boring. I’m getting

somber. My own tricks bore me.

Dorothy: Do you

want ice?

Manny: Yeah.

There’s no humor anymore and all the glamour’s dead. You notice

that? I can’t even stand how they come to rehearsal. They come

to rehearsal dressed in terrible clothes.

Dorothy: Manny,

I’m dying. I’m dying. I know I’m dying because I’m getting tired.

It’s always the same. You talk. I sleep. If I’d known what a

boring man you were when I married you, I wouldn’t have gone through

all those emotional crises.

She means it,

but she doesn’t mean it, but she really does mean it.

He pours her

a drink. They awkwardly try to embrace. Just as they get it right,

the phone rings. He leaves to answer it.

If

given this text to direct one could come up with plausible intentions

for the actors. Manny wants to get drunk, wants to share his pain

with his wife, or wants to communicate with her. Dorothy wants

to get along with her husband or wants to connect to ease her loneliness.

The point is there are very workable intentions in the text for

these two characters and these intentions or similar ones may have

been used in the development of this part of the scene by Zohra

Lambert and Ben Gazzara.

One

can, of course, never know what process Cassavetes used to develop

the performances in this scene, but the result is totally unexpected

from what the text indicates. The result appears to violate all

conventional wisdom on performance. The actors do not give the

characters a clear intention. We don’t know what they want. They

seem needy, but we don’t know what they need. There is not a clear

goal that moves the action forward. One cannot deduce the subtext

of these two characters. Much of the multiplicity or ambiguity

of motivation is carried in their gesture and physicality.

Whatever

the subtext is the actors are playing, which we cannot tell from

the scene, it does not seem to match the text. By playing what

appear to be multiple subtexts at all times, although we do not

know exactly what these subtexts are, we get two highly original,

deeply complex performances which show two human beings in some

kind of state of pain, boredom, and passivity who are unable to

communicate. She means it, but she doesn’t mean it, but she really

does mean it, but she doesn’t care anyway. This is all conveyed

in the strangely graceful way Lambert’s body goes “in all directions

at once.” Some of the complexity in performance style or Strindberg’s

“ambiguity of motive” one finds in a Cassavetes’s film may come

from his choice to have the actors play a subtext or, more likely,

several subtexts that do not correspond in the expected way to his

written text. What is clear is that this is exactly the style of

performance Cassavetes was trying to achieve because he thought

it closer to how people “really” act.

The scene continues.

Manny picks up the phone in the bedroom.

Manny: Hello.

Oh, Myrtle. No, Sweetheart, I’m still up. I’m sorry you’re not

feeling well. You have a fever? What? What girl? The young girl

got killed in front of the theater tonight. Alright, Sweetheart.

Dorothy: It’s

4:30 in the morning.

Manny: Yes, I

know it’s lonely. I hate out of town, too. Of course, I love you.

Hold it, will you please. It’s nothing. It’s just my wife. Right.

Of course, I’ll leave the phone on. Yeah. She doesn’t mind at

all.

Dorothy: Tell

her you’ll talk to her in the morning.

Manny: I don’t

sleep anyway.

Dorothy: You’ll

see her in the morning.

Manny: (to

Myrtle) Right.

Dorothy: Right.

Manny: Right. There’s no one I love more than you this moment.

You know I love you. (to Dorothy) What? (to Myrtle) Yes, Sweetheart.

Okay. Well, what’s wrong with being slapped. (to Dorothy who distracts

him) Cut it out. (to Myrtle) Just a second. (to Dorothy) Cut

it out, will you please? There is nothing humiliating about it.

You’re on the stage for crissake. He’s not slapping you for real.

Myrtle. Ah, Myrtle. Myrtle. It has nothing to do with being a

woman. Now, you’re not a woman, anyway. No, no, you’re a beautiful

woman. I was kidding. And you see, you have no sense of humor.

I told you that. I don’t want to argue with it, darling. We’ll

rehearse it. Well, how... If we don’t rehearse it, we won’t get

it. But it’s not humiliating. It’s a tradition. Actresses get

slapped. It’s a tradition. You want to be a star. You want to

be unsympathetic? It’s mandatory you get hit. That’s it. Now

go to sleep.

He hangs up the

phone.

Manny: A young

girl got killed by the theater tonight.

We cut to the

rehearsal scene where Myrtle gets slapped.

During Manny’s

phone conversation, Dorothy dances into the room daintily holding

her robe out as if it were a ball gown. She bourees to him

as he sits at the top of the bed. She jumps on the bed and pretends

to swim on her back. She goes into a pretend boxing match, catches

one of her blows on her chin and falls back rolling off the bed

onto the floor. She leaves the room.

In

this part of the scene, Manny has three goals: (1) he wants to soothe

and comfort Myrtle so she’ll behave at the rehearsal the next day;

(2) he wants to assure his wife that he loves her; and (3) he wants

to test his ability to control Myrtle. Along with these three subtexts,

which he plays simultaneously, he is also testing his sexual powers

and past attraction to Myrtle with whom he presumably has had an

affair. He wants to really assure her so she’ll continue in the

role but at the same time that he reassures her of his “undying

devotion,” he is playing with her and even making fun of himself

to himself. In addition to all this, Ben Gazzara’s performance

adds to the main theme of boredom and ennui. This theme is carried

by the dialogue but also we see it in his posture, his unvoiced

sighs, and his face. Manny has done it all before.

During

this scene, Zohra Lambert, as Dorothy, plays various objectives:

(1) to get Manny’s attention, (2) to show she has a place in the

world (she matters), and (3) to do this without really demanding

his attention since his livelihood (and hers) depends on his ability

to handle Myrtle. She also contributes to the larger theme of the

film, boredom, as well as a theme specific to her character as someone

who stands outside the emotional machinations of life. She lives

on the perimeter. When Lambert dances, pantomimes, and horses around

falling off the bed, she is not only revealing Dorothy’s character

as a meek, non-participant--as an observer outside the main action

of her husband’s life--but she also reveals her need to hold Manny’s

attention as he soothes the extravagant Myrtle. She cares, but

she really doesn’t care. Her ambiguity of motive is carried only

through her physicality, not by the dialogue.

In

a later scene, when Myrtle storms out of the theater with Sarah

chasing her, Dorothy stands in the background, against the wall,

out of the situation, unobserved, unnoticed, withdrawn from the

sturm und drang of Myrtle’s emotional roller-coaster

ride. Dorothy has the traits of the non-participant, a recurring

minor character found in many Cassavetes’s films. She is one of

several characters throughout his films who insulate themselves

from “the perils of emotional exploration.” 7

Many

of Cassavetes’s characters are also inarticulate, only able to express

themselves in fits and starts. Cassavetes finds way and opportunities

for these characters, such as Dorothy, to be revealed through physicality

because the very nature of their character makes words less appropriate.

However, just as the dialogue of the characters has various subtexts

at work under it, so does the movement and gesture. The physicality

of his actors can be as expressive, and complex, as what they say.

For example, when Myrtle sits at the table at the seance her body

movement and gesture, especially the way she smokes her cigarette

in defiance, tell us that she will not participate. She is cornered,

trapped, and ready “to jump out of her skin.” Cassavetes strategy

of using multiple subtexts simultaneously works with and without

words.

Playing with

Performance

At

the end of the film, Myrtle arrives at the theater falling-down

drunk and proceeds to work her way through the opening-night performance.

Gradually sobering up, she gains control of herself by the final

scene of the play. As Maurice passes by her backstage to make his

entrance, she says “I’ll bury him” and when she goes on stage,

she forces the scene into an improvisation he must pick up on.

Rowlands and Cassavetes thus perform two actors in a play performing

an improv in a “theatrical” acting style--rather hammy and playing

to the audience. We are very aware of the skill Rowlands and Cassavetes

have to move from a naturalistic performance style to a theatrical

one. In addition, the improv reiterates one of the major themes

of the film and answers one of the major dramatic questions (a Cassavetes

work is never limited to one major dramatic question)--what gives

meaning to life? The answer is: all there is, is love, or said

another way, love may be all there is. In addition, the scene

sets itself up against the notion that the lines are not all that

important (we see the various reactions Sarah, David, and Manny

have to the improv as they sit in the audience). The scene implies

that the best (and perhaps the only) way to get through life is

to improvise as we make the best of what we can.

The

last scene in the film is shot in a documentary-style with people

coming backstage for the opening night reception. Here the “real”

and “filmic real” break down entirely. We see Seymour Cassel and

Peter Falk, long time associates of Cassavetes. The last line of

the film is Manny introducing Peter Bogdanovich, as himself, to

Dorothy: “Do you know Peter Bogdanovich?” She brushes past him

to approach Myrtle.

Cassavetes

is again playing here as he has throughout the film. As Carney

points out, Cassavetes set himself up against the working methods

of Lee Strasberg’s Actors Studio calling their process “organized

introversion” (Cassavetes on Cassavetes 52) Like Brecht,

who at the end of his career moved away from his didactic “epic”

theater to a freer, more playful approach, Cassavetes believed acting

should be fun and playful, not the serious, laborious work he attributed

to the Actors Studio. As Carney says, “In Strasberg’s vision,

the theater was a church; in Cassavetes’ it was a playground” (Cassavetes

on Cassavetes 53).

Conclusion

Modernist

tendencies bear on the whole of Cassavetes’s enterprise. His films,

though highly idiosyncratic, nevertheless present characters that

belong to the modernist tradition. He creates centered, individualized,

and unique characters who struggle with basic human problems and

emotions. The performance style he develops with his actors is

a reaction to and a departure from performance styles that belong

to classic Hollywood “realist” films. By breaking with

the conventions of “realistic” movie dialogue, he compels his actors

to create a performance style that works against the conventions

of cinematic “realistic” performances.8

His

directorial choices in terms of the technical aspects of his films

are marked by a self-consciousness and by a simplicity and functionalism

designed to disrupt the “realist” conventions of Hollywood films. It was not only that he could

not afford the Hollywood methods of filmmaking (and he couldn’t),

but that he saw the studio process as an obstacle to the kind of

performances in which he was interested. He describes the Hollywood set from the point of view of the

actor and then adds: “And a different kind of acting is born of

that, and that is a professionalism, a professional, theatrical

kind of acting, which all actors have done” (Carney, Cassavetes

on Cassavetes 44). He wanted to find another way of making

films and to do that he had to eliminate the “pictorially perfected”

shot and the “auditorally perfected” soundtrack and the shooting

techniques used to create them.9 However, the self-reflexive

aspects of his filmmaking techniques arise from issues of functionality,

not a political agenda.

Christopher

Innes argues that naturalism, as a historical style in theater,

introduced “a quintessentially modern approach, and defined the

qualities of modern drama” (1). Since the terms “naturalism”

and “realism” are particularly ambiguous, he suggests that both

terms need to be understood as applying to the historical movement

as a whole (6).10 However, Innes locates a “subtle distinction”

that he believes adds to a “greater critical precision.” He argues

that, “it would be logical to use ‘Naturalism’ to refer to the theoretical

basis shared by all the dramatists who formed the movement, and

their approach to representing the world. ‘Realism’ could then

apply to the intended effect, and the stage techniques associated

with it” (6). His distinction allows both terms to be used for

the same play, “with each term describing a different aspect of

the work” (6). Applying this distinction to film, we see that John

Cassavetes’s films are “realistic” in terms of their intended effect,

but they do no follow the techniques and conventions that comprise

classical “Hollywood realism.” Cassavetes shares the

“theoretical basis” of theatrical naturalism because his defining

characteristic is “character in situation.” He is not interested

in the emotions of a character, but how a character acts and reacts

to a given situation.

Burt Lane, who formed an actors’ workshop with

Cassavetes in the late 1950s, differentiates their approach from

that of the Actors Studio: “In focusing on core emotions, it [the

Method] removed the masks of the characters and deprived them of

personalities. In real life, we rarely act directly from our emotions.

Feeling is simply the first link in a chain. It is followed by

an adjustment of the individual to the situation and to the other

people involved in it, and this in turn leads to the projection

of an attitude which initiates the involvement with other persons”

(Carney, Cassavetes on Cassavetes 53).11 What

is uniquely original about the performance style in a Cassavetes

film and what makes watching a Cassavetes film a consistently demanding,

but exhilarating, experience is the sense that we are in the presence

of an artist who is completely non-compromising.

Works Cited

Benedetti, Robert.

The Actor at Work. 8th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2001.

Berliner, Todd.

“Hollywood Movie Dialogue and the ‘Real Realism’ of John Cassavetes.” Film Quarterly 52:3 (Spring 1999): 2-16.

Carney, Ray.

American Dreaming: The Films of John Cassavetes and the

American Experience. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

___. Cassavetes

on Cassavetes. London: Farber and Faber, 2001.

___. The Films

of John Cassavetes: Pragmatism, Modernism, and the Movies.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

___. Shadows.

London: British film Institute, 2001.

Gritten, David.

“Names Upstairs and Down.” Los

Angeles

Times,

4 Nov. 2001: Calendar, 73.

Innes, Christopher.

A Sourcebook on Naturalist Theater. London: Routledge, 2000.

Jacobus, Lee

A. The Bedford

Introduction to Drama. 4th ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2001.

Ludington, Townsend,

ed. A Modern Mosaic: Art and Modernism

in the United

States.

Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Stanislavsky,

Konstantin. An Actor Prepares. Trans. Elizabeth Hapgood.

Theater Arts Books, 1936.

Williams, Raymond.

Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. London: Fontana, 1976.

___. English

Drama, Forms and Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977.

Cast List:

Character Player

Myrtle Gordon

actor Gena Rowlands

Maurice Adams

actor John Cassavetes

Manny Victor

director Ben Gazzara

Dorothy Victor

his wife Zohra Lampert

Sarah Goode

playwright Joan Blondell

David Samuels

producer Paul Stewart

Nancy Stein

fan Laura Johnson

Notes

1. I use the

term “Cassavetes films,” as a group, to refer only to the eight

films over which he had complete control.

2. Ray

Carney presents an extensive discussion of the connection of

Cassavetes with the Modernist movement and Italian neorealism in

A Modern Mosaic: Art and Modernism in the United States,

edited by Townsend Ludington (Chapel Hill: University of North

Carolina Press, 2000).

3. This is a

major theme in Ray Carney’s extensive work on Cassavetes and

appears in various places such as Carney’s American Dreaming:

The Films of John Cassavetes and the American Experience (Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1985).

4. In Cassavetes

on Cassavetes (London: Farber and Faber, 2001),

Ray Carney reiternates numerous examples of

material in Opening Night that comes directly from Cassavetes’s

and Rowlands’s professional experiences.

5. Ray

Carney spent 11 years compiling all possible material from

interviews with Cassavetes. He then edited, structured, and wrote

invaluable explanations making sense of this extensive amount of

material which culminated in Cassavetes on Cassavetes, a

book Carney calls the autobiography Cassavetes would have written.

Carney once and for all clears up innumerable questions and ambiguities

about Cassavetes which Cassavetes himself had propagated. The book

provides deeply rich insights into Cassavetes as a person and as

an artist. For more information see Carney’s web site which can

be accessed through www.Cassavetes.com.

6. Quotations

from Opening Night are my transcriptions.

7. Ray Carney, The Films of John Cassavetes:

Pragmatism, Modernism, and the Movies (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1994), 240. Carney cites examples of this recurring

character type in other Cassavetes films within his discussion of

Love Streams.

8. See Todd Berliner’s

“Hollywood Movie Dialogue and the ‘Real Realism’ of John Cassavetes”

(Film Quarterly 52:3 (Spring 1999): 2-16) for an interesting analysis

of Cassavetes’s dialogue.

9. It would have

been interesting to see John Cassavetes’s reaction to Mike Leigh’s

work as well as the films of Dogma 95. One also wonders what he

might have done with the now-available digital video systems.

10. Raymond Williams,

among many others, has tackled the ambiguity between naturalism

and realism. See Williams, Keywords: A Vocabulary of

Culture and Society (London: Fontana, 1976) and English Drama,

Forms and Development (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

1977).

11. Ray

Carney provides a longer discussion of Cassavetes’s relation

to the Method in his book Shadows (London: British film Institute, 2001).

GO BACK BIBLIOGRAPHY

|