Making

a Life

In this time of economic hardship,

what do you recommend for people just entering a career in filmmaking?

I’m

always uncomfortable with the notion of a “career” in anything. American

society is structured so that it opulently rewards certain roles (lawyers,

doctors, celebrity actors and athletes, wheeler-dealer businessmen,

con-man stockbrokers, big-talking producers) and ignores or financially

penalizes others (teachers, nurses, mothers, caregivers, ministers,

artists). That never changes, in good times or bad.

We focus too much on the financial side. That’s Hollywood thinking. If you are a real artist, you can make art with

no money. Red Grooms used house paint and plywood to make his art. Paul

Zaloom sets up a card table and moves toy soldiers around. Todd Haynes

used Barbie dolls. I know a guy, Freddie Curchack, who made finger-shadows

on a sheet as his art. An artist who complains about not having enough

money is not an artist, but a businessman.

The only reason to make a movie, paint a painting, or write

a poem is to try to understand something that matters to you that you

don’t understand. God knows, it’s only the reason I write my books.

If I were in it for the money, the fame, or the glory, I would have

thrown in the towel and declared bankruptcy a long time ago! [Laughs]

You do it for the challenge and fun of picking your way through a jungle

of unresolved ideas and feelings. The filmmakers I know who don’t have

the twenty thousand dollars it takes to make a movie are busy writing

short stories or putting on plays with their friends. The beauty of

that is that when they are able to get things together to make

a movie, they already have a head start on something to film. They have

tested it by tinkering with it and writing it out. They have workshopped

it and seen where it needs to be revised. I tell students who say they

can’t afford a digital camera and sound equipment to put on a play in

their living rooms or hide out in their basements and write a novel.

If they tell me they’re not interested in doing that, then I know they’re

not artists. They are more interested in having a career than a life.

But they have to make a living.

I know that, but

all I can deal with is the education side of it, and education is not

about making a living, but making a life. A deep, spiritually meaningful

life. It is a time for exploration and discovery. You’re right. Every

day after my students graduate, the world will be demanding its pound

of flesh from them. There will be pressures placed on them to compromise,

to put their values aside and do things the established way, the way

that makes money, the way that makes for worldly success. That’s why

a university is such a special place. It is their one opportunity to

do something for truth. Not for money. Not to get ahead. Not to curry

favor with someone. Not to please anyone but themselves. It is a special

time of life, a unique opportunity to go as far as they can, to dig

as deep as they dare into the meaning of life. It is a time to study

their hearts and souls and not worry about the ridiculous, wasteful,

stupid things the world wants them to care about. To go to school to

try to build a resumé, or to learn secrets about how to get rich or famous

is to waste this glorious opportunity to break free from that oppressive

system. The only right reason to go to school or to make art or to study

art is to begin to understand truths the world suppresses and denies,

and eventually to be able to share your understandings with others in

acts of love and giving.

Just this afternoon I just spoke at a Boston U. open house

"visiting day" for grad students who were visiting a number

of different schools and told them if some teacher or Dean stood up

in a meeting and told them that if they got a degree from their school

they could be rich or famous some day, they should run for the door.

I told them that the only reason to go to grad school was to have a

chance to explore themselves and our crazy, messed up culture so that

they might begin to understand themselves and it – and eventually be

able to communicate that understanding to others. To do anything else

is to waste your education, and ultimately to waste your life. It is

to sell your soul to the devil. Life is not about making money or getting

famous or being successful. In our brief time here we must try to understand

who we are and what really matters, and try to bring our feelings of

love and kindness and understanding to others to change the world for

the better in some way. That's what school is about – or what it should

be about. Starting out on – or continuing – that great adventure of

discovery and self-discovery.

Film

School

Sometimes it seems like we have a

very “everyone for themselves” attitude in the film industry in the

U.S.,

which leaves little room for cultivating a master-student relationship.

Also, to be unique and progressive as an artist often seems to imply

to trash, not build upon, the past. Do you agree with this observation,

and if you do, do you see any filmmakers out there trying to build upon

a sense of film tradition and history in their individual styles?

Rob

Nilsson said something very interesting in a Res column. He said

that film schools should be abolished and all the young people should

go find some low-budget independent filmmaker whose works they loved,

apprentice themselves to him or her, and give their tuition money to

the filmmaker. Of course, the proposal was tongue in cheek. He knows

it will never happen, and that it sounds insane to most people. But

I would love to have young filmmakers take him seriously. It could change

the history of American film. I’ve given my students this advice, but

they always think I’m joking.

Rob

Nilsson said something very interesting in a Res column. He said

that film schools should be abolished and all the young people should

go find some low-budget independent filmmaker whose works they loved,

apprentice themselves to him or her, and give their tuition money to

the filmmaker. Of course, the proposal was tongue in cheek. He knows

it will never happen, and that it sounds insane to most people. But

I would love to have young filmmakers take him seriously. It could change

the history of American film. I’ve given my students this advice, but

they always think I’m joking.

Film school is a waste of time for most students. In fact,

it’s counterproductive in most cases because the wrong things are taught

– like explaining away your characters’ mysteries by providing unnecessary

background information, and how to keep the stupid plot moving along.

Why should every movie look like every other movie? Even children’s

books are more different from one another than Hollywood films are. Who says you have to have

establishing shots or over-the-shoulder shots? Who says a scene has

to be lighted or edited in a certain way? It really shows contempt for

the art. You’d never tell a musician he had to compose for particular

instruments and play in certain keys, or a painter what colors to use

or what size canvas to paint on. And what happens at the end of the

process? Another class of know-nothings is turned loose in the world

to compete with each other for a Hollywood distribution deal.

To tell the truth, most of the students I teach give up on

film after they leave school. They go into something else. It’s the

open secret of most film programs. The faculty tell the parents all

these tall tales about careers in film on visiting day before their

children enroll, but most of the film students stop doing film the day

they graduate. And the ones who go to LA and fight to get a job and

starve for a while end up pushing a dolly or stringing wires on some

big budget production that no one involved with gives a damn about.

Those are the lucky ones! For that you went to four years of film school?

To learn how to push a dolly or answer the phone for some producer?

Each of these students could have made their own feature their

own way if they had taken Nilsson’s advice and apprenticed themselves

to an indie filmmaker. Instead they go off to work in a factory every

morning, and become a tiny cog in an enormous studio machine. What a

waste of an education. What a waste of a life. They had it right in

the sixteenth century. The guild system was a much better way to learn

art.

The

University

Why do you think so many filmmakers

are drawn to teaching, besides the schedule flexibilities?

[Laughs]

Well, they have to pay the rent somehow, and the hourly rate is a few

cents better than McDonald’s! Lots of filmmakers become teachers so

they can use equipment for free or get students to help them with their

films. But I’d like to think there is a higher, nobler reason – the

dream of being part of a community of like-minded, soulful, spiritual

searchers. Universities are the last of the monasteries – the last shelter

from the capitalist way of measuring everything in terms of popularity

and profit. That makes them a wonderful place to be.

Of course I’m talking about an ideal university. There are

so few of them left. Most academic film programs – all of the best-known

ones, NYU, UCLA, USC, and the others – do not represent an alternative

to the business sickness of our culture, but are devoted to training

people to enter and compete within it. (Click here to read a concrete illustration of how students are taught "industry" perspectives and encouraged to compete to get into the system, rather than being given a critical perspective on it.) The students don’t ask questions

about the meaning of art and life. They major in vocational ed – no

different from studying auto mechanics or farming or being in beautician

school. Like I was saying, they’d rather give their students a job than

a life.

I get emails every week from students who have spent four years

majoring in film at UCLA or USC or NYU, and have never heard the name

of a single one of the art filmmakers I write or speak about mentioned

in their classes. The so-called independent films shown in their courses

are by mainstream directors like Steven Spielberg, Oliver Stone, and

John Sayles. Artistic expression is represented by someone like Hitchcock.

The students should be awarded degrees in advertising and promotion

when they graduate. That’s the only area the work of these filmmakers

represents. They’re not studying art but commerce.

The

reason I’m so familiar with these problems is that they are not taking

place in a galaxy far away from me. The Boston University film program is no different from

the UCLA one in this respect, maybe it’s worse. Just because I am in

it doesn’t mean that the program reflects my personal values. I have

to remind saucer-eyed students about this when they write me and say

they want to come to Boston University “to study with me.” Like I was Yoda!

I tell them that they will also have to study with a lot of people who

disagree with me, who argue with me, who think I’m a pain in the neck.

Boston U. churns out worker bee drones for

the studio hive the same as other programs do.

|

And now, for another perspective – a reply, as it were, to the preceding by the other side:

The following is an interview with Boston University students and alumni about Hollywood film, stars, the entertainment biz and the Boston University Film Program

A transcript of a video presentation featuring big name Hollywood producers (all Boston University alumni) and current Boston University film students:

Lauren Shuler Donner (Hollywood producer):

The heart of the film business is LA, and I would advise coming out here.

Richard Gladstein (Hollywood producer):

The studios are all here  and the agents are all here. and the agents are all here.

David Dinerstein (Hollywood producer):

It’s a stop that one has to make along the way.

Jeff Kline (Hollywood producer):

No matter how much time you spend back East studying, it’s not the same as actually being here.

Ted Harbert (Hollywood producer):

This is where it happens. This is where you need to be.

(Click here to read a statement by Ray Carney about Hollywood being the center of the universe.)

Narrator:

There’s no doubt, Hollywood is the entertainment capital of the world, and Boston University in Los Angeles can give students a taste of working and living in Southern California.

Tallie Johnson (Boston U. student):

The BU internship program set us up at Park LaBrea Apartments, which is where I am now, and it’s right in the middle of Los Angeles, so it’s close to pretty much everything.

Niki Kazakos (Boston U. student):

We’re very close to all the studios, all the production companies, and all the agents.

* * *

Eric Tovell (Boston U. student):

The staff here really connects you with the entertainment companies. They get you in there and you’re really in the center of it all.

Niki Kazakos (Boston U. student):

All the networks.

Crawford Appleby (Boston U. student):

ABC.

Woman (Boston U. student):

CBS.

Katelyn Tivnan (Boston U. student):

NBC.

Man (Boston U. student):

Universal, E Entertainment.

Niki Kazakos (Boston U. student):

And you can work on shows like...

Katelyn Tivnan (Boston U. student):

Scrubs.

Man (Boston U. student):

Entertainment Tonight.

Woman (Boston U. student):

And Desperate Housewives!

Eric Tovell (Boston U. student):

They got production companies like Film Colony, DreamWorks, HBO Films.

Katelyn Tivnan (Boston U. student):

And advertising and PR firms.

* * *

Katelyn Tivnan (Boston U. student):

Believe me, there wouldn’t be an entertainment business without the interns!

Eric Tovell (Boston U. student):

And the best thing is that you meet everyone here.

Dana Cyboski (Boston U. student):

I see the executive producers, the show directors, the actors, the writers, the editors.

Melissa Szymansky (Boston U. student):

Today I went to a meeting and they said, “Whatever ideas you have, bounce them along to us. We’ll listen, we’ll use them.”

Dana Cyboski (Boston U. student):

And while you’re just interning, you’re not just an intern.

Eric Tovell (Boston U. student):

They know my name, they ask me questions, and I ask them questions all the time.

Woman (Boston U. student)

At night, we get to hear from these bigwigs who are making films and shows that you see or hear about before anybody else in the country.

Crawford Appleby (Boston U. student):

You have to remember, even though you’re out here and you’re working for these big production companies, you have to end up doing a lot of the routine stuff.

Dana Cyboski (Boston U. student):

Making copies, getting faxes, getting people coffee.

Katelyn Tivnan (Boston U. student):

But you also get to read the latest ideas and scripts that the company’s considering.

* * *

Niki Kazakos (Boston U. student):

You get to meet celebrities, go to advanced screenings. You wouldn’t believe the people that I get to see here every week.

Crawford Appleby (Boston U. student):

I met Diane Lane.

Eric Tovell (Boston U. student):

Jimmy Kimmel, Sarah Silverman.

Niki Kazakos (Boston U. student):

Eva Longoria.

Katelyn Tivnan (Boston U. student):

We sat next to Pam Anderson and a couple of her friends.

Crawford Appleby (Boston U. student):

I had to drive out to Quentin Tarantino’s house and drop off a script.

Niki Kazakos (Boston U. student):

I saw Lindsay Lohan get into her car accident (laughter).

* * *

Crawford Appleby (Boston U. student):

They really teach you a lot about the industry. They’re really more connected to the industry than anything we could take back in Boston.

Dana Cyboski (Boston U. student):

The teachers are all professionals who are working in the entertainment business.

Niki Kazakos (Boston U. student):

They tell you about the latest shows.

Eric Tovell (Boston U. student):

They show you how Hollywood really works.

Dana Cyboski (Boston U. student):

This experience has taught me a lot.

Eric Tovell (Boston U. student):

I figured out that I really want to be a TV executive.

Woman (Boston U. student):

A line producer.

Woman (Boston U. student):

Studio executive.

Niki Kazakos (Boston U. student):

Los Angeles is awesome!

(Alex Lipschultz, a student of Ray Carney's, sent in a comic piece from The Onion about the value of student internships. Ray Carney recommends reading it to get another perspective on the experience. Click here to read it.)

|

Fear

of Flying

My

painful, awkward, fun job – it really is a lot of fun! – is to force

my students to let go of their limited understandings of art. Classes

are great, exciting, crazy tugs-of-war. They try to stay on their feet

and I try to pull the rug out from under them. To show them works that

don’t yield to their ways of understanding, works of real art that do much more complex, slippery, challenging things. But

it’s an uphill battle. The force of the whole culture is arrayed against

it. The students generally don’t appreciate the works I show or begin

to understand how they function until we have put in a lot of time together.

It can take months. One of my courses runs 70 hours over fourteen weeks,

and that’s frequently not enough time to do what I want to do. I get

emails every week from students who have been out of school for a few

years who tell me that only then are they finally beginning to see what

I was trying to show them. What do they know? They come into school having been brainwashed

by the media into believing figures like Spielberg and Tarantino are

as good as film gets. They’ve never heard of Tarkovsky or Ozu or Bresson

or Kiarostami or Rappaport. They don’t know the great works of art. Of course everything that I am saying goes against the grain

of post-60s cultural assumptions that students should have the final

say about what they study. We live in a democracy where things are supposed

to be decided by popularity. That’s how we elect our leaders. What’s

popular is what’s stocked in stores and what gets reported in our newspapers.

But that’s not how a university should work. It’s a mistake to teach

films that the students want you to teach. It’s a mistake to put works

on the syllabus because they are popular or will get a large enrollment.

If you teach what the students have heard of and want to see, you might

as well open a movie theater in the mall. My job is to show the students

movies that they haven’t heard of, movies they don’t know they want to see, movies that do things in ways they’ve never

even imagined a work can do them.

The

music department knows this. The art department knows this. The English

department knows this. The physics and math departments know this. They

don’t consult students’ wishes when they create a syllabus. They aren’t

afraid to force students to do things they’d never do on their own.

But the film department is always, at least implicitly, playing to the

audience – organizing courses around films that have gotten the most

attention over the years, and giving the students a kind of vote on

what should be taught by evaluating courses in terms of their popularity

and enrollment.

At the point they show up on campus, very few students have

any conception of what art does. Half of them come into my classes treating

film as a form of sociology or cultural history. They look at a movie

to study the depiction of women or minority groups or gays or whatever,

and they evaluate it based on how politically correct or incorrect it

is. They take out their clipboards and work down the race/class/gender/ideology

checklist. The other half profess to care about artistic expression, but

their understanding is based on these bogus pop culture notions of art.

Many think art involves glamorous photography, lush sound effects, and

beautiful settings. Some think it is about creating powerful emotions.

If it makes you feel something, it must be great art. Others think works

of art are always “unrealistic” in some way – that art involves creating

visionary– or dream-states by using fancy lighting effects, weird music,

or jumpy editing. Others think art is about employing metaphors and

various kinds of color or shape symbolism. Others think art is about

telling stories in convoluted, non-chronological ways. Others think

it’s about sneaking in hidden meanings and surprise endings. I understand

where both groups are coming from. It’s what they’ve been taught. They’ve

learned this stuff from teachers and from viewing a lot of bad movies.

Movies by Hitchcock, Welles, Spielberg, Lucas, Lynch, Stone, DePalma,

Tarantino, and the Coen brothers. And I don’t want to seem to be picking on students. A lot of

people have the same limited views of art. Artistic appreciation is

a very rare thing in our culture because exposure to art is a very rare

thing in our culture. Look at the books people read, the music they

listen to, the movies they enjoy! I travel a lot and almost always ask

the person sitting next to me what they are reading or what kind of

music they like. Maybe one in a hundred people has any interest in or

familiarity with art. Maybe it’s fewer than that. It doesn’t matter

how many years they have attended school, what they majored in, or what

degrees they hold.

What about the

grad students? They must be more sophisticated.

Oh,

the grad students are worse than the undergrads in this respect.

They have a lot of time and effort – a lot of ego – invested in their

admiration of Mulholland

Drive and Vertigo and Blue Velvet and Pulp Fiction, and fight me tooth

and nail when I try to show them the limitations of those sorts of works.

What I am doing threatens their whole world view. It makes me understand

the Marine Corps commitment to getting them when they are 18. [Laughs]

An 18-year-old is a lot easier to teach – to inspire or scare into thinking

in new ways. People in their mid-twenties or thirties don’t want to

have to think new ideas. They dig in their heels when you try to move

them in a new direction. Do you know the quote by Guillaume Appolinaire? “‘Come to the

edge,’ he said. ‘We are afraid,’ they said. ‘Come to the edge,’ he said;

and slowly, reluctantly, they came. He pushed them. And they flew.”

It’s hard to overcome the fear of falling. I mean the fear of flying.  You

also have to take into account who goes into grad school to study film.

There are some exceptions, thank God, but in general a student who decides

to get a graduate degree in film is someone who took a lot of film courses

as an undergrad and did well at them. They are people who chose to take

courses dealing with The Godfather, Blade Runner, and Psycho rather than the paintings of Rembrandt, the music of Bach,

the poetry of Emily Dickinson, or the prose of Henry James. What does

that tell you? It tells me a lot, and it’s borne out by my experience

when they come into my courses. Most of them are not readers,

not deep thinkers, not interested in serious art, and

generally not independent intellects in any sense – or they wouldn’t

have done so well in those undergraduate film courses writing papers

about 2001 and Citizen Kane. They spent their college

careers watching junky movies and writing junky papers in praise of

them. It sounds like a horrible thing for a film professor to say, but

having been a film major is generally not a very high recommendation

for the state of their emotional development and intellectual potential.

You can’t be a very sophisticated person and take Kill Bill, Schindler’s List, or Boogie Nights seriously or want to

devote your life to viewing works like these. That’s why I often try

to admit people who have majored in things other than film as undergraduates. I should say, tried. Those days are past. I recently tendered

my resignation as director of the program. I’ll step down this summer. (To read about some of the changes in the Film Study program and admissions processes that prompted Ray Carney's resignation, click here.)

You

also have to take into account who goes into grad school to study film.

There are some exceptions, thank God, but in general a student who decides

to get a graduate degree in film is someone who took a lot of film courses

as an undergrad and did well at them. They are people who chose to take

courses dealing with The Godfather, Blade Runner, and Psycho rather than the paintings of Rembrandt, the music of Bach,

the poetry of Emily Dickinson, or the prose of Henry James. What does

that tell you? It tells me a lot, and it’s borne out by my experience

when they come into my courses. Most of them are not readers,

not deep thinkers, not interested in serious art, and

generally not independent intellects in any sense – or they wouldn’t

have done so well in those undergraduate film courses writing papers

about 2001 and Citizen Kane. They spent their college

careers watching junky movies and writing junky papers in praise of

them. It sounds like a horrible thing for a film professor to say, but

having been a film major is generally not a very high recommendation

for the state of their emotional development and intellectual potential.

You can’t be a very sophisticated person and take Kill Bill, Schindler’s List, or Boogie Nights seriously or want to

devote your life to viewing works like these. That’s why I often try

to admit people who have majored in things other than film as undergraduates. I should say, tried. Those days are past. I recently tendered

my resignation as director of the program. I’ll step down this summer. (To read about some of the changes in the Film Study program and admissions processes that prompted Ray Carney's resignation, click here.)

***material

omitted that is available in the "Necessary Experiences" packet***

A fun question: If you could make

one film required curriculum for American film students, what would

it be and why? Why is this film innovative or unique?

If

I were limited to teaching one two- or three-hour film class for all

eternity, one shot to change the history of American film, I wouldn’t

show any movies! I’d have the students listen to Bach’s D-minor Double Violin Concerto or his Goldberg Variations and

ask them to try to get that into their work. Or discuss some

Eudora Welty or Alice Munro short stories. Or read some Stanley Elkin.

Or some of D.H. Lawrence’s criticism. He is the greatest critic of any

art in the last hundred years, but I defy you to find a single film

theory class that reads him. They’d rather read Jonathan Culler or David

Bordwell! Or I’d have them look at Degas. Those are things I already

do in my classes and I’m convinced that many of the students learn more

from doing them than they do from looking at any movie. If you absolutely required me to screen something, I’d use

my three hours to show short films. They are better than most features,

and would at least demonstrate that a movie doesn’t necessarily have

to tell a stupid “story,” be “entertaining,” or any of that other rot Hollywood would make us believe. What would you show? Fran

Rizzo’s Sullivan’s Last Call; Bruce Conner’s Permian Strata, Valse Triste, Take the 5:10 to Dreamland, and A Movie;

Jay Rosenblatt’s Human Remains, Pregnant Moment, I Used to

be a Filmmaker, and Restricted; Su Friedrich’s Sink or

Swim and Rules of the Road; Shirley Clarke’s Portrait

of Jason; Mike Leigh’s Afternoon, Sense of History,

and The Short and Curlies; Charlie Weiner’s Rumba. And

ten minutes from Tom Noonan’s What Happened Was, Caveh Zahedi’s A Little Stiff, Mark Rappaport’s Local Color or Scenic

Route, and Elaine May’s Mikey and Nicky. That should be

about three or four hours of stuff. If there was a little more time,

I’d add selected chunks from Bresson’s Lancelot of the Lake or Femme Douce, Renoir’s Rules of the Game, Tarkovsky’s Sacrifice or Stalker, Barbara Loden’s Wanda, John Korty’s Crazy

Quilt, Ozu’s Late Spring, or the last ten minutes of his Flavor of Green Tea over Rice.The

least the students would learn is that a film doesn’t have to look like

a Hollywood movie. That, no matter how much Entertainment

Tonight and the New York Times try to persuade us otherwise, Hollywood is a tiny and ultimately unimportant

rivulet flowing away from the great sea of art. The smart ones would

learn something about artistic structure and how the greatest movies

use something other than action to keep us caring and in the moment

– that the worst way to make a movie is to organize it around a gripping,

suspenseful plot. Plot, actions, and narrative events are the biggest

lies we can tell about what life is really about. As Tom Noonan said

to my students, just the way you say hello to a friend or shake someone’s

hand is enough to build a scene around. Life is a string of those kinds

of moments. Why are we always looking for something else to happen?

Why do we feel our lives are not already interesting enough to make

art out of?

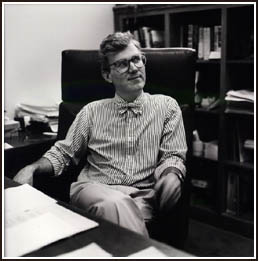

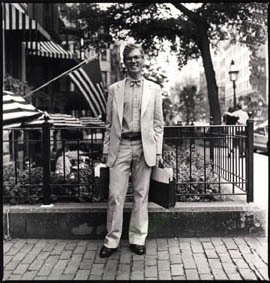

This

page contains a short section from an interview Ray Carney gave to filmmaker

Shelley Friedman. In the selection above, Ray Carney discusses the limitations

of Hollywood filmmaking and the fallacy of thinking of art in financial

terms. The complete interview covers many other topics. For more information

about Ray Carney's writing on independent film, including information

about obtaining three different interview packets in which he gives

his views on film, criticism, teaching, the life of a writer, and the

path of the artist, click

here.

To

read an interview with Ray Carney about film production programs, "Why

Film Schools Should be Abolished and Replaced with Majors in Auto Mechanics," click

here.

To read Andrei Tarkovsky's thoughts about Film School, click here.