In the 18Ėmonth period between February 2004 and August

2005, I was interviewed by more than 50 journalists about my discovery

of the first version of Shadows and Gena Rowlandsís response

to the find. Since most of the material appeared only in British or

European newspapers or on the internet (and was almost completely blackedĖout

by American journalists), I thought it would be useful to post an edited,

summary version of some of my answers to frequently asked questions

in one place.

Note that the text that follows does not represent the actual

text of any one interview, question, or answer. It is a compilation

and summary version of many similar questions asked by different interviewers

and many similar answers I gave. To avoid repetition and overlap, and

to provide the most complete picture possible, I have not only combined

questions and answers from different interviews, but, where necessary,

have rewritten and recast individual questions and answers to make the

most concise yet informative presentation of the most important information

in one place. I have also updated some of the information and corrected

the wording of my answers at many points to most accurately reflect

the current facts, the current state of affairs, and my current understanding

of events as of the date of this posting.

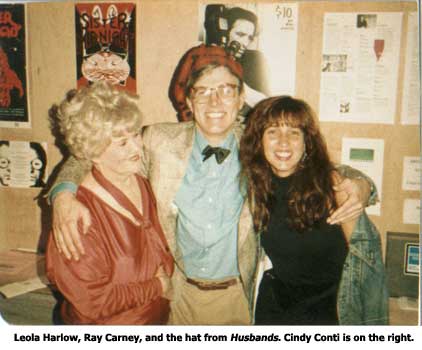

Ė Ray Carney

What

has been the response of Cassavetesí widow, Gena Rowlands, to your discovery?

What plans do you have to make the film available?

Within

days of the discovery, as soon as I had verified that the film was actually

the complete, finished, released copy of the first version of Shadows

and not just some alternate edit of the movie, I offered it to Criterion

for free for inclusion on their Cassavetes box set, but Gena Rowlands,

Cassavetes' widow, raised objections and it will not be included.

Within

days of the discovery, as soon as I had verified that the film was actually

the complete, finished, released copy of the first version of Shadows

and not just some alternate edit of the movie, I offered it to Criterion

for free for inclusion on their Cassavetes box set, but Gena Rowlands,

Cassavetes' widow, raised objections and it will not be included.

I was besieged by people who asked me about screening it at

festivals and special events. Several distributors also wanted to talk

to me about releasing it in theaters. I wanted to do what pleased Gena,

so I forwarded this information to her and told her that I wanted to

give her input into any decisions about the disposition of the film,

and of course also have her participate financially in any income it

generated. But she was absolutely opposed to having the film released

on video, shown at festivals, or screened in theaters. Ever. Under any

circumstances. By anyone. She was very clear and firm about that. Thatís

what she told the people who contacted her, and thatís what she told

me in a long phone call we had. I have copies of some of the letters

she wrote to film festival programmers and others and they say the same

thing she told me on the phone: that the version of the film I found

should never be shown, that it was never meant to be shown, that it

is not a first version of the film, and that, in fact, there is no

first version of Shadows. The faxes she sent people say exactly

those words: "There is no first version of Shadows."

The

film was unavailable for almost fifty years and believed lost forever.

You spent almost twenty years finding it. Wasnít she grateful?

That was what I thought she would be. But I was wrong.

What did you think she would say?

Well for starters, I thought sheíd thank me. Given whatís taken

place since, itís embarrassing to admit what I am going to tell you,

but Iíll be completely honest about what I thought would happen. Please

donít laugh. My fantasy was pretty fatuous. Over the years of my search, I used to imagine how happy it

would make her on the day I called her up to tell her about finding

the Shadows print Ė if I was lucky enough to succeed. I thought

she would be beside herself with joy at recovering a work by her husband

that everyone thought had been destroyed. I imagined that Iíd fly out

to her house to present the film to her and weíd have a sip of champagne

together and toast the print. Then weíd watch a video of it on her TV.

Iíd be so happy to give it her, and sheís be so glad I had found it.

Thatís not exactly the way it played out. I called her up to

tell her about it, and she was mad. Really upset. The conversation was

very tense. It was all she could do to control her anger on the telephone.

As far as she was concerned not only should the film never be shown

but the discovery should never have been announced Ė publicly or on

my web site. In fact, she told me to remove all references to it from

my site. She talked to me like I was a misbehaving child, saying: "There is no first version of

Shadows. What you found was not meant to be seen. It should never

be screened." Take a minute to think about what that means. It's

a pretty scary thought. Never is a very long time. (To read more about

this, click

here.)

I guess the tipĖoff should have been that almost the exact

same thing happened a few years before when I found a lost print of

Faces. (To read more about this, click

here.) I notified Rowlands asking if I could have a video reference

copy made by the Library of Congress for my research. I got a fax in

return from Al Ruban, the business manager of the estate, who does Genaís

bidding, telling me not only that I was not allowed to have a video

of the film made, but that I was not to announce the find or publish

anything about it! I still have that fax in my file cabinet. It was

only after I found Shadows and talked to some people about the

find that it dawned on me that the same thing could happen with it.

That Rowlands might tell me to never announce it or to write about it

Ė which is what she did. That she might attempt to suppress the discovery,

as she had with the Faces find. (To read more about this, click

here.)

Sure enough, thatís what happened. Iíll never forget my telephone

call to Rowlands to tell her about the find. In fact, I remember my

exact words when she got on the line: ďGena, I have amazing news. I

found the first version of Shadows. Isnít that wonderful?Ē There

was this long pause after I said that. Then she told me how upset she

was with me. She told me I was mistaken. She chastised me. She objected

to everything I had done and what had just been posted on my web site

about the find.

Listen, Gena is an acknowledged master at turning on the charm

and graciousness even when she is upset with someone Ė sheís a great

actress after all Ė but her charm, her acting ability, sure failed her

that day! She was beside herself with irritation. ďThanksĒ was not one

of the words that passed her lips. She was extremely peeved.

This spring [2004] has been pretty rugged. In that phone call,

Rowlands insisted that I immediately send her the print. Then she faxed

Criterion threatening a law suit if they included the film on their

disks. Criterion gave me a copy of the fax. Then when I didnít Fedex

the print to her, she sicced a team of lawyers on me to confiscate it.

And then, to top it off, she had me fired from the Criterion Cassavetes

box set, had my voice-over commentary removed, and had my name removed

from the credits, even though my work remained on the disks. I was the

scholarly advisor for the project and put eight months of my life into

it. But she threatened Peter Becker with pulling the films and killing

the project if he didn't comply with her demands, so he did her bidding

and there's no record in the set of any of the work I did on the project.

After I did the work, she had them erase my name. (To read more about this, click

here.)

Her actions speak for themselves. They opened my eyes to what

she was capable of. They really shocked and surprised me. In public,

Gena is devoted to cultivating this impression of being a gentle, sweet,

perfect "lady." In private, she plays to win. She plays hardball.

Take no prisoners. She or her henchman Ruban have shown through their

actions that they are willing to attack my career, get me fired, badmouth

me in public, or do practically anything else they can to get back at me. (Click here to read more about the dirty tricks.) Through her lawyers, she is insisting that I turn the film print and video copies over to her, and is using lawyers to try to force me to comply.

What is the basis of her claim that you have to give it to her?

There

are no sound legal or moral grounds for seizing it, but if you have

enough money to pay them, I gather lawyers can do most anything. Her

legal claim is that the print is ďstolen propertyĒ and, as such, must

be returned to the rightful owner. Do you get it? Pretty clever, eh?

If she asserts that someone stole it from Cassavetes back in the 50s

or 60s, that makes me the possessor of stolen goods, and voids any claim

I have to any right to hold onto it Ė by having found it or bought it

or obtained it subsequently in any way. When something is stolen property,

subsequent transactions are voided. Itís an ingenious legal argument.

Caught me by surprise. I would have never have thought of it. It is

just the sort of clever argument a lawyer is paid to come up with. The

only problem is that itís a complete fabrication. Itís horse manure.

Thereís no basis for it. It never happened. Throughout Cassavetesí life,

he never once claimed the film had been stolen. Or filed a report of

it being stolen. Or told anyone that it had been stolen. There is not

a shred of evidence that it was ever stolen. And plenty of evidence

that it was not. The ďstolenĒ idea a complete fiction. But what Iíve

learned Ė and what things like the O.J. Simpson and Michael Jackson

trials show Ė is that if you get enough highĖpaid lawyers to argue something

and get the right judge to hear the case, the facts donít matter.

There

are no sound legal or moral grounds for seizing it, but if you have

enough money to pay them, I gather lawyers can do most anything. Her

legal claim is that the print is ďstolen propertyĒ and, as such, must

be returned to the rightful owner. Do you get it? Pretty clever, eh?

If she asserts that someone stole it from Cassavetes back in the 50s

or 60s, that makes me the possessor of stolen goods, and voids any claim

I have to any right to hold onto it Ė by having found it or bought it

or obtained it subsequently in any way. When something is stolen property,

subsequent transactions are voided. Itís an ingenious legal argument.

Caught me by surprise. I would have never have thought of it. It is

just the sort of clever argument a lawyer is paid to come up with. The

only problem is that itís a complete fabrication. Itís horse manure.

Thereís no basis for it. It never happened. Throughout Cassavetesí life,

he never once claimed the film had been stolen. Or filed a report of

it being stolen. Or told anyone that it had been stolen. There is not

a shred of evidence that it was ever stolen. And plenty of evidence

that it was not. The ďstolenĒ idea a complete fiction. But what Iíve

learned Ė and what things like the O.J. Simpson and Michael Jackson

trials show Ė is that if you get enough highĖpaid lawyers to argue something

and get the right judge to hear the case, the facts donít matter.

And itís

not necessarily about winning the case anyway. Itís about wearing me

down with the legal bills to the point that I give up and turn the print

over to avoid spending more money to protect it. My lawyers tell me

thatís the way a lot of intellectual property cases play out. Itís a

deliberate strategy. Take ten years and wear someone down.

It costs

an arm and a leg for me to defend myself, even from a fabrication like

this. Donít overlook the fact that Rowlands is a movie star and Iím

just a regular guy. Sheís a multiĖmillionaire actress and Iím a working

stiff on a salary with bills and a mortgage. She has lawyers on retainer.

I have to go out and find someone to represent me at a thousand dollars

an hour.

We know

how that situation plays out. If you have Johnny Cochran or F. Lee Bailey

on your side, you can do anything. And even if she doesnít win the case,

she can force me into bankruptcy just defending myself. Welcome to the

American judicial system. It costs me thousands of dollars just to pay

someone to reply to her lawyerís letters. My lawyers tell me it will cost tens of thousands more if and when the case goes to court. (Click here to read another discussion of this issue.)

Why

donít you just turn the film over to her? If you say youíre not in it

to make any money off it, why are you holding onto the print?

If

I were motivated by money, thatís exactly what I would do. Holding onto

the film, trying to protect it, is the expensive thing for me to do.

If I turned it over to her tomorrow, Iíd save myself not only money, but all of the time and inconvenience of dealing with

this issue.

If

I were motivated by money, thatís exactly what I would do. Holding onto

the film, trying to protect it, is the expensive thing for me to do.

If I turned it over to her tomorrow, Iíd save myself not only money, but all of the time and inconvenience of dealing with

this issue.

But Iím not in it for the money. Iím in it to

preserve her husbandís first film so it can be seen by future generations.

To protect it. To make sure it is not destroyed. The key point you donít

want to forget for a second is that she told me, in her own words, directly, and she repeated

it more than once, that she never wants the film to be screened.

I asked her directly why she wanted me to send it to her. She said her

goal was to keep it from being seen. ďIt should never be screened.Ē

Thatís pretty close to being an exact quote of her words. When I asked

her what she was going to do with it if I sent to her Ė whether she

was going to destroy it Ė there was this long pause, and then she said

(and these are her words as precisely as I can recall them): ďI donít

know. I havenít decided what I am going to do with it. But it was never

meant to be seen.Ē

Her statement floored me. Remember this was in the same conversation

where sheís playing Rumplestiltskin and stamping her foot, insisting

that I have to send the print to her immediately. Yet, in this same

conversation, immediately before and after that, she is telling me that

if I do send her the print, no one would ever see it again. No one.

Ever. How in the world could she imagine that that was the way to persuade

me? How could I possibly, in good conscience, send it to her? It would

be immoral of me.

And donít forget, given the vehemence of her feelings, itís

not at all beyond the realm of possibility that she might even destroy

it, just to get it out of her hair and stop people from asking about

it. Iím not just imagining that part. There is a guy named Al Ruban

who manages Cassavetesí estate who told me right out that that was what

he intended to do if I ever found the print. First, he said that there

was no such print and that I was a fool to be looking for it. Then he

said, with a bit of a smirk on his face, that if I found it, heíd destroy

it. So you see I am not being paranoid. He said the same thing to someone I know, an important, highly-placed

film professional, so that when I told this other person about the find, the first thing the

other guy said to me is: ďIím worried about what Al might do if he gets

his hands on it.Ē Direct quote. (To view three brief video clips from the first version of Shadows, click here.)

Ruban has told people that you are the problem. That your refusal

to turn the film over to them is the only reason it canít be seen.

I know. Early on, Peter Becker called me up and told

me that that was what Ruban said to him, and Iíve heard reports from

others about him saying it to other people subsequently. Itís given

me an insight into how diabolical the Cassavetes operation that Rowlands

runs can be. Simultaneous with the attempt to seize the print and the

letters they sent to me, to Criterion, and to film festival directors

threatening law suits if they show the movie or make it available in

any way, Ruban launched a smear campaign trying to blame it all on me.

Ruban has been deputed by Gena to call up people and tell them that

Iím the heavy: ďIf only Ray Carney would turn over the print and the

videos to us, everything would be fine. Itís that bad Ray Carney who

refuses to send us the material. How selfish of him." -- That's not a direct

quote, but that's the gist of his remarks as they have been relayed

to me. Pretty clever, eh? I become the reason why the film

is not being shown! Then I get emails from people asking why I am refusing to "give Rowlands her film back" or

why I "haven't made the film available for screening"Ėas

if I wanted to keep the film to myself, when my goal is to share it

with the world, and Rowlands is the one who wants to prevent it from

being seen.

What are you doing in response?

Well, Iím not turning it over to her potentially to destroy,

obviously. That would be irresponsible in the extreme. Just because

she is Cassavetes' widow gives her no moral right to destroy or suppress

his first film. And also keep in mind that she is directly contravening

her own husband's wishes on this matter. When interviewers asked him

about it when he was alive Cassavetes said that he didn't want it suppressed.

He himself showed it in his own lifetime, he rented it out for screenings

in theaters, and he expressed the desire that the first version of the

film be allowed to be shown and seen. (To read more about this, click

here.)

In my phone call with her, and in subsequent letters, I proposed

all sorts of compromise positions Ė having her pick the places it would

be shown, having her attend the screenings herself if she wanted to,

abiding by her wishes in all sorts of ways. But I got absolutely nowhere.

She was unyielding. She refused to even discuss any of this with me.

Her only reply was to tell her lawyer to send out threatening letters

and to have Ruban start telling people that I was the problem for not

having sent her the print as soon as I found it.

Her lawyer has written everyone who has even expressed passing

interest in showing the film or releasing it, threatening them with

a law suit if they go near it. They did it to Criterion and lots of

festivals, theaters, and distributors. I have copies of some of the letters that were sent since the programmers sent them to me.

I was at an event where Al Ruban said that you refused to let Rowlands see the film. Is that true?

It's another one of Ruban's slanders and attempts to undermine me. It's completely false. I have offered to show the print I found to Gena many times. I proposed flying out to her house and screening it for her in our first telephone conversation and in many subsequent letters to her -- to bring it to her and screen it on video, of course, since the print is too fragile and unique to be schlepped around for that purpose. Or, if she didn't want to screen it at her house, I proposed meeting her anywhere else she would name and showing it to her in a hotel, in an office, in a movie theater -- practically anywhere. We could do it in a screening room at Boston University where I teach. I'm not reluctant -- in fact, I'd love to do that! I have copies of my letters to her, where I practically get down on my knees and beg her to let me do that. Maybe I should post them on the site. I bend over backwards trying to be accommodating. I place no conditions at all on the screening date, time, or circumstances.

The reason I'd love to show her the film is that I am convinced --or at least was convinced when I first began asking her to let me show it to her and thought she was still open-minded on this subject -- that it would show her that she is laboring under a series of mistaken assumptions. It would show here that the film I found is not in a rough state. It would show her that it does not contain anything embarrassing to her husband's reputation or anything that she would not want to be screened. It would show her that the first version of Shadows is a beautiful, independent, completely finished work of art different from the second version. She doesn't seem to understand any of that right now. As I suggested, Ruban has apparently "poisoned" her on this subject, and misinformed her. So I'd love to have her see the first version and correct her view of it. But the problem is that she refuses. She simply refuses. She wasn't interested when we spoke on the phone, and she has not responded to any of my subsequent written requests to show it to her. It's apparently one of those "don't confuse me with the facts" situations. She would rather hold onto her fantasy than actually see the film I found. Her lawyers' attempts to confiscate what I found have been her only response. And of course they haven't seen the film either! But it's not my fault. I'd love to show it to her. But Al just goes on making up things to try to turn people against me.

The Rotterdam Film Festival has an official notice on their web site saying that the screenings you conducted were unauthorized or illegal.

Yes, that's another manifestation of Rowlands's and Ruban's thuggery. They made Rotterdam post those statements attacking me and the screenings, threatening them, just like they threatened me, with legal action if they didn't post them. But the claim that I needed permission to show the film is completely bogus. Without merit. Rowlands and Ruban simply made it up. They sent the text attacking me to the Festival and told them that they insisted that it be posted on their site. The festival gave me the message that Rowlands sent them, with the text that she demanded they post, so I have all that in my files. Rotterdam, as almost any film festival would, agreed to post what Rowlands wanted just to get her off their back. Her thuggish tactics, her readiness to attack me in public (all the while keeping her own name off the attack and pretending that the statement was the idea of the Film Festival and was written by them) tell you a lot about her. Her private behavior is a little different from the public image she so carefully cultivates.

Donít

forget it is her husbandís work, after all. She technically owns it.

Thatís just not correct. If you know anything about movies,

you know that the ownership of the physical print is entirely different

from the issue of who made the movie. John Ford doesnít own his movies.

Frank Capra doesnít own his movies. Robert Altman doesnít own his movies.

Rowlands doesnít own the first version of Shadows, just because

her husband was involved in its creation.

Actually,

if you want to get into technicalities, the case is even more favorable

to me than it would be on one of Cassavetesí other films like A Woman

Under the Influence or The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. Cassavetes

wrote those movies himself. And the actors in those movies worked under contracts that assigned the ownership of those films to Cassavetes. The

first version of Shadows was a totally different situation. It

was not written by John. It was improvised by the actors who were apportioned

ownership ďsharesĒ in it. I have a few of the contracts. In my Cassavetes

on Cassavetes and Shadows books, I write about how Cassavetes

reneged on some of these promises and some of the actors and crew members

tried to sue him in the early 1960s, but he escaped by moving to California.

But the contracts are valid. He did not own the movie. The actors and

crew members did. (To learn more about this situation, scroll to the top of this page and read the material in blue.)

Actually,

if you want to get into technicalities, the case is even more favorable

to me than it would be on one of Cassavetesí other films like A Woman

Under the Influence or The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. Cassavetes

wrote those movies himself. And the actors in those movies worked under contracts that assigned the ownership of those films to Cassavetes. The

first version of Shadows was a totally different situation. It

was not written by John. It was improvised by the actors who were apportioned

ownership ďsharesĒ in it. I have a few of the contracts. In my Cassavetes

on Cassavetes and Shadows books, I write about how Cassavetes

reneged on some of these promises and some of the actors and crew members

tried to sue him in the early 1960s, but he escaped by moving to California.

But the contracts are valid. He did not own the movie. The actors and

crew members did. (To learn more about this situation, scroll to the top of this page and read the material in blue.)

On top of that, further invalidating Rowlands's claim

to own it, the first version of Shadows

was never copyrighted with the Library of Congress, never deposited

with them, never claimed for copyright by Cassavetes, and does not physically

bear a copyright mark or a claim of copyright anywhere on the print

or the packaging. And on top of all of that, it was shown publicly,

in commercial screenings for paid admission in movie theaters a number

of times before it was lost on the subway, which means that it is now

in the public domain, like many other films that were never copyrighted

or never had their copyrights renewed.

Now all of that is what I call a lawyerís argument; but it

happens to be totally and completely on my side of the issue. It means

that Gena and Cassavetesí estate not only does not own the print but

doesnít even own the rights to screen it. I do.

But

it is her husbandís work. If she doesnít own it technically or in terms

of the copyright, doesnít she at least have a moral right to possess

it? Are your motives as pure as you say? Arenít you going to make money

from the print?

Don't

forget that Rowlands has declared her intention to suppress it and possibly

destroy it. And Ruban has declared his intention to destroy it. These

are not paranoid fantasies on my part; they are facts. Are you saying

that Ė strictly for sentimental reasons, because she is the widow of

the filmmaker Ė I should turn the first version of Shadows over

to her or Ruban to be shredded or burned or locked away somewhere that

no one can ever see it again? Possibly to be destroyed, even if not

here and now, to be destroyed in fifty or a hundred years by someone

else Ė her children or whoever ends up with the estate? Are you saying

I should do that? Are you saying my motives are impure because I am

trying to preserve a major work of art? Whatís impure about that? Iím

acting out of the highest principles. Thereís nothing in this for me

but saving a work of art.

Let me make an analogy. Suppose I find an attic full of unknown

Picasso paintings somewhere in Paris. That is the equivalent to the

Shadows find in my mind. OK. So then I call up Picassoís widow

or daughter or some other surviving relative and, without even saying

thanks for the discovery, she immediately does two things: First, tells

me the paintings were never meant to be seen and that I should immediately

turn them over to her so that she can decide if they should be destroyed.

And then, when I donít send her the paintings, she turns her lawyers

loose on me to try to seize them, to try to force me to turn them over.

Now I can do either of two things in response:

Now, if I were in it strictly for the money, I would do the

first thing. Itís a noĖbrainer. Iíd turn over the paintings, get a big

bundle of money as payment for them, and to hell with preserving Picassoís

legacy. Let the widow destroy the paintings. Let her suppress them.

Let her paint mustaches on them. Who cares? I got my payment, whatís

not to like?

Now, if I do the second thing, thereís really nothing in it

for me. Itís costing me tens of thousands of dollars to try to defend

myself from the law suit. And I may be dead by the time the paintings

can finally be exhibited. So thereís no fame and glory in it for me

personally. But, in my opinion, I have done something of inestimable

value. I have saved the paintings for the next hundred thousand years.

I have made sure they wonít be destroyed by the relative.

Now I understand that most people canít follow the logic of

the second course of action because it goes against everything they

have been taught. Itís not about making money, but losing money. Most

people, even most film professors, would take the money from the widow

and wash their hands of the whole thing. No one can believe I am doing

this for the sake of the work of art. They assume some nefarious motive.

But I am a professor of art. I love art. I have devoted my life to celebrating

certain artists and works of art. I am in this strictly to protect this

film. Not to make money off it. And I am in this for eternity. Not for

a quick buck. Not to get famous or rich. I donít expect to be alive

when Gena finally drops her objections to John's first

film, which is what this print is, being shown. But the print will survive me. Thatís all I care about.

Iíve thought a lot about what I am doing, and if I do

say so myself, I think Iím one of the few people in the world who would

choose to do what I am doing. Because there is nothing in it for me

but expense and inconvenience. All of the financial arguments are against

doing it. I incur tens of thousands of dollars in legal expenses.

And I get nothing out of it. So why am I doing it? Thatís simple. Iím

doing it for John. For his memory. To preserve one of his films for

posterity, from an unfortunately misguided person who clearly doesnít

understand the filmís value and importance.

This is not about making money. Finding Shadows and searching for other Cassavetes' materials --from lost scripts to lost edits of other films -- has cost me something like fifty thousand dollars over the past decade or two. (I haven't bothered to tally it up since the money was spent over so many years, and it's too depressing to tally it up it anyway.) And this isn't the only time I have made decisions that lose money rather than make it. My writing is another way I spend money I never get back. I have devoted a good part of my life to writing about Cassavetes and other indie artists, to promoting and celebrating obscure non-Hollywood work. It should be obvious that I don't do it for the money. I'd be writing about something else if I wanted to make a profit on it. I lose twenty or thirty thousand dollars - or more than that - every time I write a book. I spend years of my

life flying around the U.S. going to film archives to do research, visiting

filmmakers to interview them, going to film festivals to view things. I run up enormous hotel and airplane bills. I pay exorbitant fees to

archives and libraries to get xerox copies of unpublished manuscripts

made so I can study them. I spend thousands of dollars having copies

of unavailable, unreleased films or interviews transferred to video

or audio so I can listen to them or look at them and write about them.

I pay photo permissions fees out of my own pocket in most cases. Publishers

won't pay for those sorts of things and my university won't pay for

it. In financial terms, it's almost all a loss. Gallons of red ink.

My books never return that kind of profit. I donít make a tenth of it

back. But so what? Iím not doing it for the money. Iím doing it for

the same reasons I am doing this. For art. For posterity. Not

for money. (Click

here and here

to read more about the costs involved in serious, scholarly publishing.)

Why not deposit

the print in an archive so that Rowlands cannot destroy it?

I

actually tried to do that, way back when I discovered the film. I contacted

Martin Scorseseís Film Foundation and the head of the UCLA Film and

Television Archive about preserving, copying, and depositing the print.

Itís too much to go into now, but both places basically turned me down.

They were scared to get involved because they didnít want to alienate

Rowlands! Itís funny, isnít it? Neither place was really interested

in doing the right thing or could see it as a moral issue or an important

preservation cause. All they cared about was ďmaking Gena madĒ (thatís

how one of them put it) or losing her support for a future project or

donation. UCLA is counting on Gena giving them money and other things.

They ďdonít want to jeopardize their relationship with her.Ē I think

those were their exact words to me. Itís pretty pathetic, but thatís

how the world works Ė the film world and the rest of the world I gather.

The financial tail wags the artistic dog. They didnít want to touch

the print without Genaís blessing.

I

actually tried to do that, way back when I discovered the film. I contacted

Martin Scorseseís Film Foundation and the head of the UCLA Film and

Television Archive about preserving, copying, and depositing the print.

Itís too much to go into now, but both places basically turned me down.

They were scared to get involved because they didnít want to alienate

Rowlands! Itís funny, isnít it? Neither place was really interested

in doing the right thing or could see it as a moral issue or an important

preservation cause. All they cared about was ďmaking Gena madĒ (thatís

how one of them put it) or losing her support for a future project or

donation. UCLA is counting on Gena giving them money and other things.

They ďdonít want to jeopardize their relationship with her.Ē I think

those were their exact words to me. Itís pretty pathetic, but thatís

how the world works Ė the film world and the rest of the world I gather.

The financial tail wags the artistic dog. They didnít want to touch

the print without Genaís blessing.

Of course once I learned that about Scorsese and UCLA and the

Film Foundation, I realized that giving the print to them would not

be a way of keeping Gena from getting it and destroying it. Given the

way they suckĖup to her, handing it over to UCLA would be equivalent

to turning it over to Ruban.

You were incredibly

lucky to find the print. Are you this lucky in everything?

Luck had nothing to do with

it. Nothing happens by fate or luck or destiny. Nothing is meant to

be. All the odds were against finding the print. Read the Robert Frost

poem, "Mowing," about the dream of "easy gold at hand

of fay or elf" if you want to know what I think about luck.

On the other hand, work can

accomplish anything. Doing, not wishing. Acting, not being. We make

everything what it is. Doing anything valuable takes time and effort

and struggle. People forget the struggle part. The path of greatest

resistance is the only way to get anywhere valuable. If you're doing

something valuable, it's always a struggle against infinite resistance

- against fearful people and bad ideas and stupid rules. Our culture

is pervaded by forces that resist excellence: forces of stupidity, commercialism,

screwed-up values, sycophancy, fear, the desire to please someone else,

the ways things have been done in the past. That's the reality of the

world. And anyone who attempts to do anything creative has to fight

it. I deal with it everyday on my job.

Of course the culture doesn't

want you to know that. Movie stars, the media, and presidents of corporations

all try to make you think that the system recognizes and promotes excellence

and virtue, when it fact it does everything in its power to promote

mediocrity and sameness and going-along with what is. That's what you

have to fight. Even one person can change the world if they work at

it. I'm not claiming I'm doing that of course, but it's worth noting.

The operant word is work.

That's why I have no patience

with TV shows that treat life as a joke. Or with Hollywood movies that

pluck our sentimental heartstrings. They pacify us. They keep us in

our seats. They want us to entertain ourselves to death - as Neil Postman

put it. They want to keep us laughing - or crying - while our culture

sails over the edge of the abyss. That's the problem I have with everyone

from Spike Jonz to the Coen Brothers. They hide the mess we are making

of our lives with goofball jokes and stunts. That's not what life really

is about. Life is about making something humanly valuable out of the

mess we live in. I'm sick and tired of entertainment. I'm fed up with

escapism, which is what most of our lives are already about, outside

the movies. Give me a movie that takes me out of my everyday state of

emotional denial and escapism, a movie that makes me want to run out

of the theater before it's over and do something about the world. Give

me a movie that makes me want to change my life. Give me a movie that

makes me think I'm wasting my life. Those kinds of films are worth seeing.

The rest is junk. And our culture is up to its eyes and ears in it already.

Sorry for the sermon! I know I got off-topic, but you got me started!

What contemporary filmmakers do you think are influenced by Cassavetes?

I get a stream of emails asking me that question. Often from

programmers at film festivals or special events. But itís a bogus concept

invented by bad reviewers and idiot professors. Itís a fraudulent notion.

It applies to pop culture, where everything is imitating everything

else. It doesnít apply to art.

Any

artist worth his or her salt is unique, sui generis, distinctive,

one of a kind. Of course, at the same time, every great artist is influenced

by everything else around him or her, even as the artist may attempt

to shake off and deny the influences. Harold Bloom talks about that.

The greatest danger is starting to imitate yourself. Itís a sign of

artistic death. Look

at the careers of Robert DeNiro, Nicholas Cage, and Meryl Streep. Or Oliver Stone. Itís paintĖbyĖnumbers. You find a formula

that works and stick to it. Thatís not art; thatís massĖproduction.

Art is never just going through the motions; itís always new. It always

involves taking chances. Itís always about daring to fail.

Any

artist worth his or her salt is unique, sui generis, distinctive,

one of a kind. Of course, at the same time, every great artist is influenced

by everything else around him or her, even as the artist may attempt

to shake off and deny the influences. Harold Bloom talks about that.

The greatest danger is starting to imitate yourself. Itís a sign of

artistic death. Look

at the careers of Robert DeNiro, Nicholas Cage, and Meryl Streep. Or Oliver Stone. Itís paintĖbyĖnumbers. You find a formula

that works and stick to it. Thatís not art; thatís massĖproduction.

Art is never just going through the motions; itís always new. It always

involves taking chances. Itís always about daring to fail.

Picasso had the right idea: "I am influenced by no one.

Especially not myself." Success can make you do that. Money can

bribe you into it. Growing old can do it to you. Maybe it was good that

Cassavetes never was really commercially successful and didnít have

a chance to get really old. His films are as different from one another

as they are from everyone elseís work.

To be an imitator Ė even an imitator of Cassavetes, even if

you are Cassavetes Ė is to turn yourself into a hack. To try to make

a Cassavetean film is to prove that you are no Cassavetes. He didnít

imitate anyone. Even himself. As someone once said, influence is influenza

Ė a sickness. Look at my reply to Terrence Malick on the web site. Read

Emersonís ďThe American Scholar.Ē He talks about this. Look at the final

quote I put in the Cassavetes on Cassavetes book. I put it there

for a reason.

Let me put it in a different way. What recent filmmakers are fulfilling

Cassavetes' vision? His work is more celebrated that it has ever been

before. That is certainly a good thing.

Itís a terrible idea for anyone to fulfill Cassavetes'

vision. They should fulfill their own vision Ė their own feelings about

life. Thatís the old influence fallacy one more time. Itís a sickness.

As to Cassavetesí work being celebrated: Thatís meaningless. People

are sheep. They used to hate his work when it was fashionable to hate

it. Now they love it when it is fashionable to love it. But nothing

has really changed. Itís all lip service. While the media are chasing

the latest cinematic firetruck Ė spilling ink over the latest piece

of junk created by Oliver Stone and Mel Gibson Ė there are currentĖgeneration

Cassavetes-level filmmakers in New York and San Francisco making movies

they can't get into theaters that never get into the newspapers. That

hasnít changed and never will change. The next Cassavetes will be as

neglected as the last one. Thatís the history of art. Norman Rockwell

always outdraws Barbara Loden and John Korty.