|

In

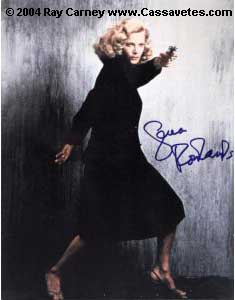

the end, Cassavetes said that he agreed to do the film largely as

a favor

to Rowlands, who relished the idea of playing a larger-than-life role.

The role deeply appealed to her. It tapped into a side of her that

captured

the way she sometimes thought of herself – the "sexy but tough

woman who doesn't really need a man" personality type that described

many

of the

actresses she had idolized over the years. Or one might say that Cassavetes

was having fun with her love for Marlene Dietrich (whom Gloria resembles

in many subtle ways). In

the end, Cassavetes said that he agreed to do the film largely as

a favor

to Rowlands, who relished the idea of playing a larger-than-life role.

The role deeply appealed to her. It tapped into a side of her that

captured

the way she sometimes thought of herself – the "sexy but tough

woman who doesn't really need a man" personality type that described

many

of the

actresses she had idolized over the years. Or one might say that Cassavetes

was having fun with her love for Marlene Dietrich (whom Gloria resembles

in many subtle ways).

Though she really wanted to

do it, she doesn't go about this very easily, you know. After the

picture

was written and the deal was made, she said, "Maybe you ought to get

someone else." [Laughs.] Which is always maddening. On every film that

we've

ever

made, she has enormous trepidations before she goes out and acts, but

it's not because she can't act, but because she doesn't know whether

she's

capable of speaking for a bunch of women who are childless, and she wants

to represent them truthfully. She doesn't want to represent them as

caricatures,

she wants to represent the people she's playing with some authenticity

as to what they are feeling, what they would feel in a certain circumstance

and in a way that not many actresses do. She's an artist. And her holdbacks

are her pain. I mean, she went through a tremendous amount of pain

thinking

she's not good enough to play these things. Once she starts going she

forgets "I'm not good enough" and the scenes hold her in check and

she

just keeps on going as long as she can.

Cassavetes

was always in awe of what Rowlands could do with a script – even a weak

one. Cassavetes

was always in awe of what Rowlands could do with a script – even a weak

one.

Gena is subtle, delicate.

She's a miracle. She's straight. She believes in what she believes

in. She's

capable of anything. It's only because of Gena's enormous capacity to

perform that we have a movie, because a lot of people would be a little

bit too thin to work on it. Gena is a very interesting woman and for

my money the best player that is around. She can just play. Give her

anything

and she'll always be creative. She doesn't try to make it different – she

just is – because

the way she thinks is different from the way most actors think. She

goes in and she says, "Who do I like on this picture?

What characters do I like, what characters am I so-so about?" I picked

up her script once and I saw all these notes, all about what reaction

she had to the various people both in the production and the story. It

was very personal to her, and I felt very guilty that I'd snooped. Then

I watched her work. She sets the initial premise and follows the script

very completely. Very rarely will she improvise, though she does in

her

head and in her personal thoughts. Everybody else is going boom! boom!

boom!, but Gena is very dedicated and pure. She doesn't care if it's

cinematic,

doesn't care where the camera is, doesn't care if she looks good – doesn't

care about anything except that you believe her. She caught the rhythm

of that woman living a life she'd never seen. When she's ready to kill,

I'm amazed at how coldly she does it.

Cassavetes'

father, to whom he was very close, died on 26 April 1979, during the final

weeks of preparations to shoot, which possibly contributed to the film's

autumnal feel and its striking emphasis on death. Three weeks were reserved

for rehearsals. Shooting began at the former Concourse Plaza Hotel on

161st Street in the South Bronx, which was the set for the seedy apartment

building at the beginning of the film. In the 1960s, it had become a home

for welfare families, but it had been abandoned for four years at the

point Cassavetes found it. An apartment house at 800 Riverside Drive (at

158th Street) served as the location for three of the nice apartments:

Gloria's sister's place; the final hotel room Phil waits in; and mob leader

Tony Tanzini's headquarters. Cassavetes loved the history both locations

wore on their walls and had to struggle to keep Rene D'Auriac and the

Columbia set-design crew from cleaning them up or retouching the graffiti

on the Concourse Plaza.

In the beginning, I had to

instruct them in bad taste, but now they're beginning to revel in it.

For the outdoor shots,

Cassavetes deliberately picked non-glamorized, non-touristy sections

of the city

to avoid the "Woody Allen movie" feeling. For the outdoor shots,

Cassavetes deliberately picked non-glamorized, non-touristy sections

of the city

to avoid the "Woody Allen movie" feeling.

I love New York! I grew up

there, and it seemed to me that all the pictures that are made about

New

York never concentrate on neighbor hoods. And New York to me is comprised

of a series of neighborhoods. But I didn't want people to just say,

"'OK.

Now we're here. Now we're on 57th Street. Now we're on 58th Street."

It was very important not to make the scenery be the center of attention,

because, I don't know, I just feel there should be some more respect

given to life than to the making of a film.

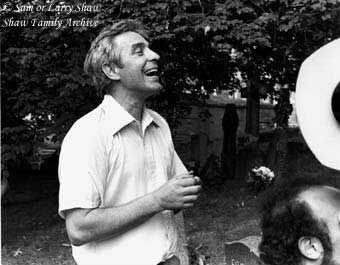

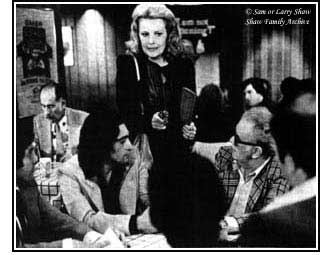

Producer Sam Shaw helped

to select the locations. Since he had been friends with Romare Bearden

and written a book about his work, he suggested using his watercolors

for the title cards. (Shaw had a lot of input into the artwork used in

all of Cassavetes' films and a couple of years before had provided the

photographs that were used in Marty and Virginia's apartment in Opening

Night.)

As part of his effort to

break away from Hollywood clichés, Cassavetes and Shaw rounded

up actual gangsters and various street-people for the scene in Tony Tanzini's

apartment. Cassavetes solicited their opinion about whether this was the

way things would really happen. The man Gloria shoots on her way to the

elevator, for example, was an actual professional hit man, with fifteen

years' experience, who got into an argument with Cassavetes about how

the scene would have really taken place if he were running things.

The aspect of the film that

came in for the most criticism from reviewers was Juan Adames' performance.

They came in apparently expecting him to be cute and cuddly in the Little

Miss Marker mode. When he wasn't, they judged that Cassavetes had

failed. What they overlooked was that Cassavetes deliberately worked hard

to avoid sentimentality (of which the Sidney Lumet/Sharon Stone remake

is guilty).

The kid is neither sympathetic

nor non-sympathetic. He's just a kid. He reminds me of me, constantly

in shock, reacting to this unfathomable environment. He was always full

of excitement and wonderment as to what he was doing, trying to comprehend

this fathomless story of a family being wiped out. The kid is neither sympathetic

nor non-sympathetic. He's just a kid. He reminds me of me, constantly

in shock, reacting to this unfathomable environment. He was always full

of excitement and wonderment as to what he was doing, trying to comprehend

this fathomless story of a family being wiped out.

To

add to the toughness of the performance, Gena Rowlands didn't come out

of character between takes and was as cool to Adames when they weren't

filming as when they were. She felt that if she treated him any differently

on the set than her character was in the movie, it would only confuse

the boy and potentially spoil their scenes. Cassavetes endorsed her decision

(and in fact wanted her to be even tougher and harder on him than she

chose to be). An aspect of the film that Cassavetes may not have even

been conscious of was that Phil, the midget macho man, was an emotional,

if not a literal, self-portrait of the artist, and Rowlands' treatment

of the pint-sized Puerto Rican tough-guy was a comical rendition of her

real-life relationship with her swaggering husband.

She and the kid found an amazing

restraint. Most people today say, "Tell me you like me, tell me you

love

me." People need that reassurance, that confirmation of things that should

be self-evident. But these characters go on the basis that there are

certain

emotions and rules that go beyond words and assurances. They just know.

I like that part of the movie. The kid is Puerto Rican. The woman

is a

blonde of a type who might not ordinarily think a Hispanic was the highest

member of society. Even when they're thrown together, they don't pretend

to care about each other because it's fashionable. So at the end, when

they do care about each other, it's because of their personal trust

and

regard. And that's a beautiful thing to see. She and the kid found an amazing

restraint. Most people today say, "Tell me you like me, tell me you

love

me." People need that reassurance, that confirmation of things that should

be self-evident. But these characters go on the basis that there are

certain

emotions and rules that go beyond words and assurances. They just know.

I like that part of the movie. The kid is Puerto Rican. The woman

is a

blonde of a type who might not ordinarily think a Hispanic was the highest

member of society. Even when they're thrown together, they don't pretend

to care about each other because it's fashionable. So at the end, when

they do care about each other, it's because of their personal trust

and

regard. And that's a beautiful thing to see.

The main interest of the

film, for Cassavetes, was the character of Gloria.

It was about a woman who beyond

her control stood up for a kid whom she wanted nothing to do with.

Gena's

character was of a very simple person that loved her life and having

to give it up for a Puerto Rican kid in New York City; it's like if

I meet

somebody and they say, "Hey man, can you help me? I'm in a lot of trouble,

and I'm going to be killed." It's one thing to be killed. But it's

another

thing to give up everything that you own in life, all your friends, your

whole way of life. So I think this woman gives up her whole way of

life,

and she does it in such a fashion that you believe her, and that's basically

the picture. If that works, then I think the picture works.

Gloria celebrates the

coming together of a woman who neither likes nor understands children

and a boy who believes he's man enough to stand on his own. There's

a

lot of pain connected with raising children in today's world. It's

considered a big holdback for a woman. So a lot of women have developed

a distrust

of children. I wanted to tell women that they don't have to like children

– but there's still something deep in them that relates to children,

and

this separates them from men in a good way. This inner understanding

of kids is something very deep and instinctive. In a way, it's the

other

side of insanity. But we had to be careful how we evoked this in the

movie. We avoided anything like a traditional

mother-son relationship. Gloria doesn't know why she's doing any of

these things. She's lost by it, and

that's the way I feel. I'm lost by life. I don't know anything about

life. If I make a movie, I don't even understand why I'm making the

movie. I

just know that there's something there. Later on, we all get to know

what it's about through the opinions of others. Gloria celebrates the

coming together of a woman who neither likes nor understands children

and a boy who believes he's man enough to stand on his own. There's

a

lot of pain connected with raising children in today's world. It's

considered a big holdback for a woman. So a lot of women have developed

a distrust

of children. I wanted to tell women that they don't have to like children

– but there's still something deep in them that relates to children,

and

this separates them from men in a good way. This inner understanding

of kids is something very deep and instinctive. In a way, it's the

other

side of insanity. But we had to be careful how we evoked this in the

movie. We avoided anything like a traditional

mother-son relationship. Gloria doesn't know why she's doing any of

these things. She's lost by it, and

that's the way I feel. I'm lost by life. I don't know anything about

life. If I make a movie, I don't even understand why I'm making the

movie. I

just know that there's something there. Later on, we all get to know

what it's about through the opinions of others.

***

Cassavetes' responses to

common critical objections to the film:

–On why Buck Henry didn't

pack and leave earlier.

You never can leave early. You always think now I'm gonna run out

and get out of town, but if you have a wife, you understand that she has

to get ready, and if you have a child or two kids, then you realize that

they have to get ready. And if you have two kids and a grandmother, there's

an awful lot of packing to be done. So you can say let's go a million

times to your wife and family, and they're still going to be late.

–On why the gangsters weren't

better organized: –On why the gangsters weren't

better organized:

I consider gangsters to be the same as regular people, the only difference

is that they're willing to kill somebody. I don't consider gangsters anything

more than that except they have a deeper limit of what the tolerance of

the human spirit will allow. And I don't think they're smarter than anybody

else. I don't think they're smarter than I am.

–On why Gloria wasn't searched

before she met the boss.

I

think that's protocol. I think it's OK to blow away small mob figures,

guys that are trying to kill you, or trying to kill somebody involved

with you. But when you walk into the head Mafia guy's house, and they're

like ten people in the room – and this woman had been the head

man's mistress – I don't think there's any doubt that she wouldn't

be searched,

because no

one in the world would ever expect her to try to walk out of that place.

It's such a come-down in position to search somebody. Can you imagine

the Secretary of State of the United States going to Russia to see the

top Commissar and being searched? You wouldn't be searched. Even with

them, there's some kind of politeness.

–On why the gangsters didn't

just shoot Gloria when she came in. –On why the gangsters didn't

just shoot Gloria when she came in.

It's not a bunch of guys that the minute a woman gives herself up,

that they take her off and put her in cement and throw her in a river.

[It's] difficult for the head guy, who has bought her jewels, as he says,

and he's gone to bed with her, and who's lived with her, to just pull

the trigger. It's never easy. I think that it's only in movies that it's

easy. The hell with it. And I like to deal with people who have a little

bit more feeling than just the stereotype – [unlike other movies

where it's] the kiss of death and then it's over with.

The end sequence, when the

Phil is praying beside the tombstone and Gloria gets out of the limo,

was originally in black-and-white.

I would say that fifty per cent of the people like it in black-and-white

and fifty per cent of the people like the color. And a lot of people

don't

like the ending no matter what happens! In honesty, I think the

ending is not as good as it could be. [I just did it that way] because

I really didn't want the kid to suffer. What kind of picture would it

be if at the end the kid went to pieces? I just didn't want to kill off

the person who had protected that boy.

Cassavetes always regarded

Gloria as a pot-boiler. Since it was his most "conventional,"

"Hollywood" movie, it was ironically appropriate

that American reviewers (including The New York Times' Vincent

Canby, who had panned Cassavetes' previous films), pronounced it his "finest work,"

but even with the reviewers' support, Gloria did only mediocre

business at the box office. Cassavetes, Rowlands, and Adames could not

come anywhere near the drawing power of Zeffirelli, Dunaway, and Schroder.

It

was television fare as a screenplay, but handled by the actors to make

to better. It's an adult fairy tale. And I never pretended it was anything

else but fiction. I always thought I understood [it]. And I was bored

because I knew the answer to that picture the minute we began. And that's

why I could never be wildly enthusiastic about the picture – because

it's so simple. Whereas Husbands is not simple, whereas A Woman

Under the Influence is not simple, Opening Night is not simple.

You have to think about those pictures. The next picture we make will

be a

deep personal statement. I don't know if anyone will finance it. Fortunately,

[now] I have some money.... It

was television fare as a screenplay, but handled by the actors to make

to better. It's an adult fairy tale. And I never pretended it was anything

else but fiction. I always thought I understood [it]. And I was bored

because I knew the answer to that picture the minute we began. And that's

why I could never be wildly enthusiastic about the picture – because

it's so simple. Whereas Husbands is not simple, whereas A Woman

Under the Influence is not simple, Opening Night is not simple.

You have to think about those pictures. The next picture we make will

be a

deep personal statement. I don't know if anyone will finance it. Fortunately,

[now] I have some money....

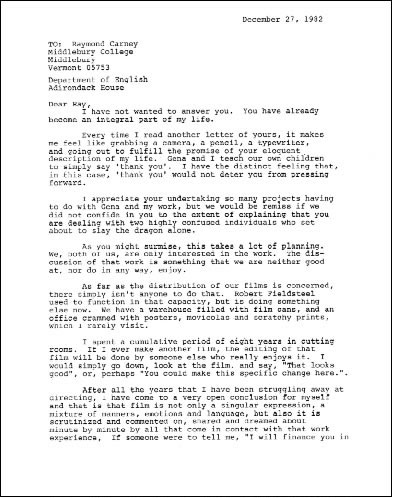

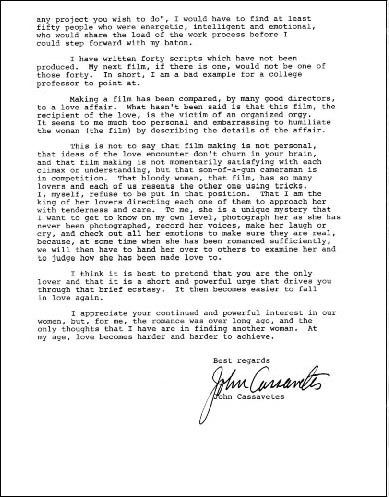

This

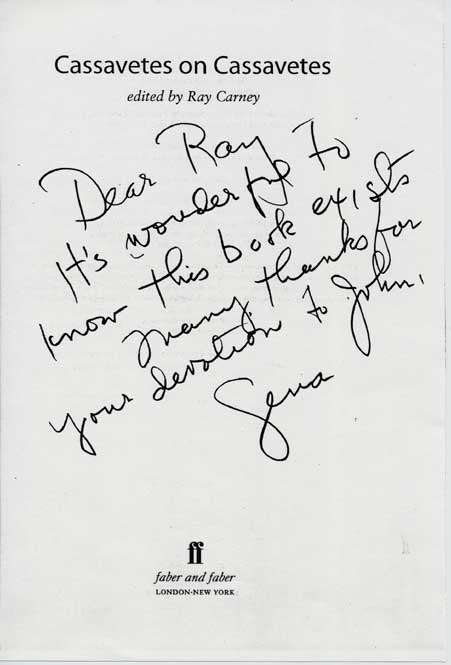

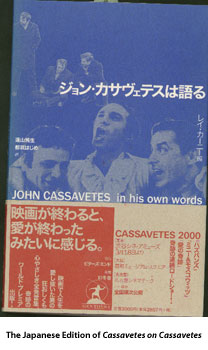

page only contains excerpts and selected passages from Ray Carney's writing

about John Cassavetes. To obtain the complete text as well as the complete

texts of many pieces about Cassavetes that are not included on the web

site, click

here.

|