|

Michael

Fitzhenry: As far as English-language critics

go, you’re pretty much the guy on Cassavetes. Michael

Fitzhenry: As far as English-language critics

go, you’re pretty much the guy on Cassavetes.

Ray Carney: By default! I wish my

name had been Pauline Kael or Vincent Canby. I could have made more of

a difference over the years. It shows how hopeless most American reviewers

are—I won’t dignify them by calling them critics. But I shouldn’t bash

journalists. Film professors are worse—even more behind the time, even

less open to new ideas!

MF: Have you ever thought that maybe

Cassavetes’ films aren’t really that hot?

RC: (laughter) That’s actually the

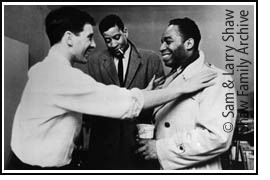

position I started from! I had a conversation a few years ago with Ben

Gazzara where he comically referred to newspaper reviewers as "slow

learners" when it came to Cassavetes’ work. We were doing a retrospective

and they were still panning the movies! Recycling their reviews from twenty

years earlier. Well, I’m ashamed to admit it, but I was a slow learner

myself. I fought a number of the films tooth and nail before I finally,

very gradually, came to terms with them.

I’ll never forget the first time I walked

into a Cassavetes movie. It was Faces, many years ago. I was a

college student who had never even heard of Cassavetes, simply looking

for something to see on a Saturday night. I remember it as clearly as

if it were yesterday—not because I enjoyed the film but because I couldn’t

stand it. It was too intense, too demanding, too disorienting—just too

much. I stormed out five minutes into the first reel. I’ll never forget the first time I walked

into a Cassavetes movie. It was Faces, many years ago. I was a

college student who had never even heard of Cassavetes, simply looking

for something to see on a Saturday night. I remember it as clearly as

if it were yesterday—not because I enjoyed the film but because I couldn’t

stand it. It was too intense, too demanding, too disorienting—just too

much. I stormed out five minutes into the first reel.

I went back to the same movie theater about

a week later to give the film one more try, only to walk out again after

about a half hour. Then a few days later, I did something inexplicable

even to myself: I went back yet a third time and finally managed to sit

through the whole film—by this point as completely confused about my own

state of confusion as I was about the film itself.

I didn’t have the faintest idea what it was

that simultaneously drove me away and kept drawing me back. When I’d walked

out of other movies, I sure hadn’t gone back to see them again! All I

knew was that movies weren’t supposed to be like this. Faces offended,

violated, upset me in a way no film had ever done before. It reached me

in a deeper place. Other movies, even at their most serious, their most

emotionally engrossing, were not threatening, not disorienting in this

way. What did this filmmaker think he was doing? Who did he think he was?

I still secretly thought it was all a fluke—something

about my personal life that made me overreact. (I was having serious girlfriend

problems.) It was only after I saw Minnie and Moskowitz and A

Woman Under the Influence—walking in on them more or less by accident

too—that it slowly began to dawn on me that maybe, just maybe this filmmaker

was doing something entirely different from other films I had seen.

All of my writing is really just an attempt

to understand my own confusion, I guess. I’m now convinced that the greatest

art always does something like that. It doesn’t give us what we want,

but what we need.

* * *

RC:

In both life and art, Cassavetes was interested in the moments when our

patterns are disrupted. He was interested in the moments when we’re left

a little exposed and vulnerable. Those moments when some of the little

routines that get us through life break down. That’s the subject of the

films. He was supersensitive to those little emotional routines we’re

trapped in and don’t know it. RC:

In both life and art, Cassavetes was interested in the moments when our

patterns are disrupted. He was interested in the moments when we’re left

a little exposed and vulnerable. Those moments when some of the little

routines that get us through life break down. That’s the subject of the

films. He was supersensitive to those little emotional routines we’re

trapped in and don’t know it.

For me personally, this side of him came

out in conversation in the way he could look at someone and instantly

"do" them. He was extraordinarily perceptive about people, all

those little things that make us us. I’d be eating lunch with him, someone

would come up to the table, and the second they were gone, or in the middle

of a story about them, he would momentarily switch into their voice and

gestures. He had a sixth sense for sniffing out people’s emotional and

intellectual habits, the patterns of thinking we are enslaved to and don’t

even recognize. If someone was there—a waitress or whatever—he would push

their buttons to try to see if he could get them out of them, or at least

make them see them. He would say or do almost anything!

He pushed my buttons too—said things to "get

to me" or tease me or test me. Saying things about my opinions about

his work, for example. I’d praise a movie and he’d put it down. ("Oh,

you like my entertainment picture," he said patronizingly,

when I told him how wonderful I thought Minnie and Moskowitz was.

"I think I’ll really be remembered only as an actor. That’s my best

work"—when I praised his directing.) But then if I criticized a scene,

he would defend it! When it didn’t make me laugh, it really got to me

at times. He loved to test people. The very fact that I still remember

all this stuff shows that he pushed buttons that have stayed pushed!

But it was not in life but in the films that

it was done most brilliantly. He wanted to trip up people’s routines,

mess with their minds—both viewers and characters. Look at Faces.

It’s about Super Salesmen—guys who can sell anybody anything at anytime,

but what John was interested in was the moment their sales pitches are

no longer sufficient, the times a raw emotion comes out. Look at The

Killing of a Chinese Bookie. Cosmo Vitelli thinks he’s figured out

life and that it all comes down to a carnation and a tuxedo jacket, and

if you just look classy or charming or stylish everything is going to

go smooth. Then suddenly he gets tangled up with the Mob and finds out

what reality is. But it was not in life but in the films that

it was done most brilliantly. He wanted to trip up people’s routines,

mess with their minds—both viewers and characters. Look at Faces.

It’s about Super Salesmen—guys who can sell anybody anything at anytime,

but what John was interested in was the moment their sales pitches are

no longer sufficient, the times a raw emotion comes out. Look at The

Killing of a Chinese Bookie. Cosmo Vitelli thinks he’s figured out

life and that it all comes down to a carnation and a tuxedo jacket, and

if you just look classy or charming or stylish everything is going to

go smooth. Then suddenly he gets tangled up with the Mob and finds out

what reality is.

MF: So do you think that was a prime

goal for Cassavetes? To investigate those sort of ideas about performance

or self?

RC: Let me make something clear. Cassavetes

would hate this way of talking about his movies! He’s scream at us. He’d

throw something. Or laugh with that wonderful cackle. It’s too abstract

and intellectual. There was a deep strain in him that not only didn’t

understand but was antipathetic to the idea of being an intellectual or

a critic. He’d say to me, why do you want to write about these films anyway?

He thought I was wasting my time. His interest in experience was as it

was lived, and he tries to get those raw moments into the movies. People

who intellectualize, people who rise above the mess by making a theory

about it, are people he didn’t understand and didn’t trust. They are the

ones he puts in his movies. He just never got around to intellectuals

and critics. Probably didn’t think they were important enough! Boy, would

the French be shocked by that! (laughs)

MF: At no point would he intellectualize

what he was trying to accomplish? Like how’d he feel about, for example,

Cosmo slipping out of the role he’d been performing so comfortably? MF: At no point would he intellectualize

what he was trying to accomplish? Like how’d he feel about, for example,

Cosmo slipping out of the role he’d been performing so comfortably?

RC: John was a profoundly instinctual

artist. He didn’t understand people or experiences abstractly, but practically.

He had what Hemingway called an unfailing bullshit detector when he saw

something. He could tell if someone was faking it. He could tell if they

were coasting on a routine. He could tell if they had some fancy-schmancy

theory about what they were doing that was just for their own vanity.

His art came from his gut reactions about life.

You ask about Cosmo. Ben Gazzara told me

that when he was playing the role, he was having great difficulty understanding

it. As an actor, he was uncomfortable and bewildered. One night he said

to John, "I just don’t understand who this guy is." And John

took him aside, and they huddled together in the back seat of a car. And

John started crying. Now I don’t know if the crying was an act or if it

was sincere, but I don’t really care. John started crying, and looked

at Ben and said, "Ben, do you know who those gangsters are? They’re

all those people who keep you and me from our dreams. All the Suits, all

the people who stop the artist from doing what he wants to do. That’s

what you are as Cosmo. You’re somebody that just wants to be left alone

to do what you want to do. And there’s all the bullshit that comes in,

all these Suits that come in and start messing up your life. Why does

it have to be like that?"

Does that make clear what it is to be an

instinctual artist? John didn’t make the movie based on some idea about

life. It wasn’t born out of some theory. Bookie wasn’t abstract

to him. It was personal! You couldn’t get further from movies like Pulp

Fiction and L.A. Confidential. Bookie wasn’t created

to play with the genre. It wasn’t written and edited to spring

a series of surprises on the viewer, or open narrative trap doors under

him. It wasn’t about playing games with expectations, tricks with how

to tell a story. It wasn’t about goofing on formulas and styles. It was

real. It mattered. It was John’s life. It was about the Suits, the producers,

the fancy contract guys who come in and say "sign here" and

get in the way.

John didn’t go into a film with a theory

about "systems of expression" or "meanings in motion"

or "pragmatic understandings"—all that stuff I translate him

into. He didn’t understand or care for theory and criticism. He didn’t

think that abstractly. But he was so in touch with his own feelings and

experiences that he almost stumbled into insights about the ways we fall

into emotional traps, the ways we imprison ourselves in our own conceptions

of ourselves. His works are intellectually profound and theoretically

revolutionary in the extreme, but their insights came from life, not from

theory—from feeling not from thinking. That’s of course the best place

to get them. The truest place.

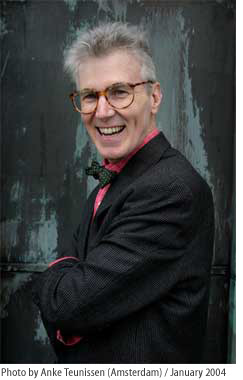

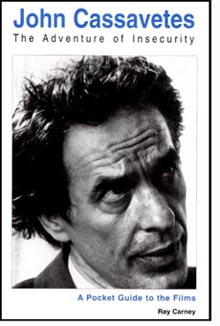

This

page only contains excerpts from an interview with Ray Carney, the author

of John Cassavetes: The Adventure of Insecurity. To learn how to

obtain the book, please click

here.

|