Tillich's Theological Influence on Thomas Merton

(1915-1968)

|

|

|

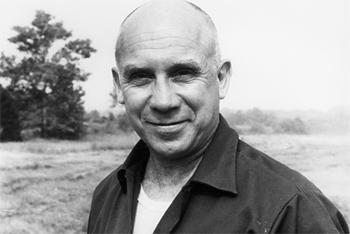

Photo of Thomas Merton by

Robert Lax (from

here) |

The formative theology of

Protestant theologian, Paul Tillich, has shaped

theological thinkers throughout the 20th and 21st

centuries. Tillich’s theology pushed the boundaries of

existential thought and encouraged other theologians to

do the same in their own theologies. However, unlike

many major theologians, who inspire others to adopt

their theology in carbon-copy fashion, Tillich’s

systematic theology inspired theologians to take pieces

of his thought and springboard from it into their own

theologies. At times, this makes it quite difficult to

trace Tillich’s influence on other theologians within

their theological writings. Nevertheless, one theologian

who was clearly influenced by Tillich to form his own

theological understandings was Trappist monk, Thomas

Merton. Tillich’s thought can be traced through several

of Merton’s books, especially in the form of

similarities in God-language and existential questions,

and Merton’s approach to faith and symbols.

Thomas Merton, born in France in

1915, was a contemporary of Paul Tillich. In 1938,

Merton converted to Catholicism and in 1941 he joined

the Trappist abbey, Our Lady of Gethsemane near

Bardstown, Kentucky. At Gethsemane, Merton spent his

time in solitude and became a prolific writer and

theologian for the Catholic Church. During Merton’s

twenty-seven years at Gethsemane, his writing took many

different forms, including letters, poetry, biographies,

novels, and journals, with many of his pieces being

published posthumously. Just as diverse as the mediums

through which he developed his theology was his subject

matter, which covered topics such as social ethics,

mysticism, interreligious dialogue, Zen, contemplation,

and mediation. As Merton’s theology matured, he began to

become involved in Buddhist-Christian interreligious

dialogue. In 1968, just three years after Tillich’s

death, Merton died in Bangkok, Thailand, where he had

spoken at an interfaith conference between Catholic and

non-Christian monks and nuns (Merton.org).

Unlike Tillich, Merton’s

theological thought is not organized systematically, but

his theological leanings are very present in his

writings on all subjects, some of which are clearly

influenced by Tillich. Merton even cites Tillich’s

influence directly several times around his conceptions

of faith and symbols. Furthermore, there is

correspondence between the two thinkers. In a letter

written by Merton on September 4, 1958 in response to

Tillich sending a signed copy of his book, Love Power

and Justice, Merton expands on several Tillichian

notions. In particular, Merton analyzes Tillich’s notion

of “ultimate concern,” humanity’s concern for the ground

of being. While initially expressing his worry that it

cannot include faith, Merton eventually embraces

Tillich’s notion of faith, writing, “… looking at it

from the angle of ‘the power of being,’ your idea of

faith becomes for me very noble, as well as attractive,

when you point out that the power of faith is measured

by its capacity to assume and rise above ‘existential

doubt’” (The Hidden Ground of Love, 577). Faith,

as the courage to face doubt, becomes a major theme for

Merton.

In a chapter on “Creative Silence”

in the book Love and Living, published after

Merton’s death, Merton uses Tillich’s notion of faith as

a means to rise above doubt. Merton writes on positive

and negative silence, saying of positive silence that it

“can be presence, awareness, unification,

self-discovery,” while negative silence “can be a

regression and an escape, a loss of self.” Creative

silence, another term for positive silence, “demands a

certain kind of faith.” Merton compares this “faith”

with “what Paul Tillich called the ‘courage to be.’”

Merton understands the dark, abyssal side of coming

“face to face with ourselves in the lonely ground of our

own being….” Merton continues on to describe what

Tillich would call “existential doubt.” It is clear here

that Merton found hope in Tillich’s notions of faith as

a “courage to be” in the face of extreme doubt and used

it throughout his writings on faith (39).

In this same book by Merton, we see

another example of Tillich’s influence on Merton. The

chapter “Symbolism: Communication or Communion” is

heavily influenced by Tillich’s notions of symbols. For

both Merton and Tillich, “The symbol is not an object

for its own sake: it is a reminder that we are summoned

to a deeper spiritual awareness, far beyond the level of

subject and object …. [T]he symbol is an object which

leads beyond the realm of division where subject and

object stand over against one another” (72-73). Merton

uses this definition of symbol, provided by Tillich, to

discuss symbols as communion as opposed to

communication. Merton writes, “…the symbol goes beyond

communication to communion. Communication takes place

between subject and object, but communion is beyond the

division: it is a sharing in basic unity” (73).

Merton continues in this chapter to

expand on the importance of symbols. For Merton,

Tillich’s notions of symbols play a role in sacrament

and our centeredness in God. Merton writes, a symbol

“…is an embodiment of that truth, a ‘sacrament,’ by

which one participates in the religious presence of the

saving and illuminating One” (74). For Merton, as well

as Tillich, symbols point to a unity between the Divine

and humanity that is present and represented in all of

creation. “[A symbol] proclaims that, in one way or

another, according to the diversity of religions, the

believer can and does even now return to Him from Whom

he first came” (74-75).

Merton also writes on the dangers

of broken symbols. He agrees with Tillich, writing,

“When the symbol degenerates into a mere means of

communication and ceases to be a sign of communion, it

becomes an idol, insofar as it seems to point to an

object with which it brings the subject into effective,

quasi-magical, psychological, or parapsychological

communication” (76). Merton takes this opportunity to

point to idols of his day, such as nationalism and

military superiority. This reflects Tillich’s concerns

in their shared post-World War II world (76).

|

|

|

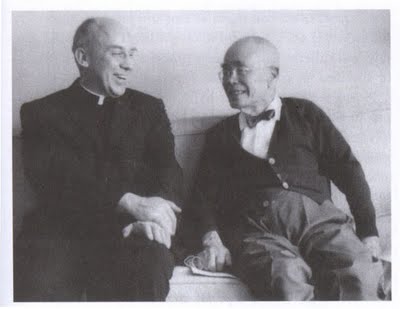

Merton and D. T. Suzuki (from

here) |

Had Merton not died at such a young

age, he may have applied Tillichian thought to

interreligious dialogue with Buddhism to a fuller

extent. As it was, both Merton and Tillich had

dialogical relationships with Dr. D. T. Suzuki, a

Buddhist philosopher and psychoanalyst in Japan. In

Zen and the Birds of Appetite, Merton refers to

Tillich a number of times while discussing the

philosophy of Dr. Suzuki, pointing to St. Augustine as

the central thinker that brings these three (Suzuki,

Tillich, Merton) together (64). Tillich visited with Dr.

Suzuki during his visit to Japan in 1960 (Ashbrook, 41).

Paul Tillich influenced many

theologians in various ways that led them to take an

idea discovered in Tillich’s systematic writings and

expand and adapt it to their own theological thinking.

Thomas Merton did just that in his theological writings

on faith and symbols. Merton was inspired by Tillich’s

concepts of faith and “the courage to be” in the face of

existential doubt, something that was close to both of

their lives. He also was able to adopt Tillich’s ideas

around symbols and applied them sacramentally to

Catholic theology. It seems a shame that these two men

were not closer colleagues given their shared interest

in interreligious dialogue. Considering they both were

close with Dr. Suzuki and his theological dialogues in

Japan, one would think they would have worked closer in

closing the ecumenical-gaps between Catholics and

Protestants, as well as on dialogue between Christians

and representatives of other world religions.

Bibliography

Ashbrook, James B. “Paul Tillich

Converses with Psychotherapists.” Journal of Religion

and Health. Vol. 11, no. 1 (1972): 40-72.

Merton, Thomas. Love and Living.

Edited by Naomi Burton Stone and Brother Patrick Hart.

New York: A Harvest/HBJ Book, 1985.

Merton, Thomas. The Hidden

Ground of Love. Edited by William H. Shannon. New

York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1985. 575-577.

Merton, Thomas. Zen and the

Birds of Appetite. New York: New Directions. 1968.

“Thomas Merton’s Life and Work.”

www.Merton.org.

The information on this page is copyright ©1994 onwards, Wesley

Wildman (basic information here), unless otherwise

noted. If you want to use text or ideas that you find here, please be careful to acknowledge this site as

your source, and remember also to credit the original author of what you use,

where that is applicable. If you have corrections or want to make comments,

please contact me at the feedback address for permission.

|