Ray Carney wrote the following program note for the theatrical adaptation of Wim Wenders's Wings of Desire created by Toneelgroep Amsterdam, which played in Amsterdam, Belgium, and the Netherlands in October and November 2006, and was presented at Harvard University's Loeb Drama Center by the American Repertory Theater from November 25 through December 17, 2006.

Falling into the World:

Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire

Ray Carney

“I have always found that angels have the vanity to speak of themselves as the only wise; this they do with a confident insolence sprouting from systematic reasoning.”

— William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

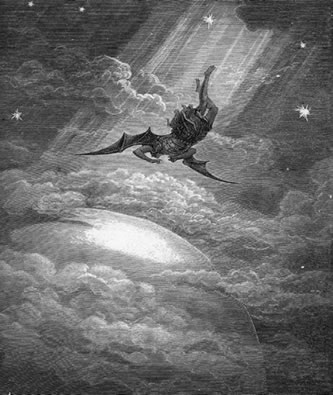

From Jacob to George Bailey, men have wrestled with angels and angels have wrestled with men. The twist Wim Wenders gives the story in Wings of Desire is to have angels wrestle with themselves. The last artist to do that was John Milton and the angel was named Satan.

From Jacob to George Bailey, men have wrestled with angels and angels have wrestled with men. The twist Wim Wenders gives the story in Wings of Desire is to have angels wrestle with themselves. The last artist to do that was John Milton and the angel was named Satan.

Wenders’ angels are neither guardian nor avenging. They are witnesses – ideal observers who move from time to time, place to place, and person to person, eavesdropping on the most secret thoughts, most private moments in peoples’ lives – and deaths.

The controlling metaphor of the film is that the earthly characters inhabit a world of endless, ubiquitous walls. It is not accidental that Wenders sets his film in Berlin at the height of the Cold War. At the point the movie was made, the city was politically, ideologically, and linguistically sliced up like a jig–saw puzzle and the wall that separated East from West was an omnipresent fact. As if those national and geopolitical divisions aren’t bad enough, Wenders further separates and segregates his characters within a series of boxes within boxes: the rooms, businesses, factories, institutions, and glass and metal cocoons – or coffins – they call their cars.

But the most important walls that alienate and estrange individuals in Wings of Desire are imaginative and emotional – the personal barriers and boundaries that individuals erect around themselves that separate parent from child, husband from wife, boyfriend from girlfriend, and individuals from their own more hopeful selves. The initial scenes of the film – in the apartment building, on the highway, and on the subway – present an anthology of the ways people lock themselves in mental prisons of their own creation. Wenders’ camera sweeps across a panorama of states of self–created ontological solitary confinement defined by characters’ despairs, fears, doubts, and disappointments. Wenders positions characters behind car windows and windshields or shoots them standing on the other side of plate–glass windows to suggest the extent to which even when someone is conspicuously visible, he or she can still be cut off imaginatively, sequestered in his or her own private emotional world, trapped in the secrecy of consciousness. Notwithstanding all of its crowds and groups, the world Wenders presents is a frighteningly lonely place, one in which both angels and men have ample reason to declare: why this is hell nor am I out of it.

Wenders imagines only a few openings in this world of walls – a few possibilities of breaking out of the prison of solipsism into forms of personal freedom, connection, and interaction. Two occur at the bottom of the chain of being and two at the top. On the primitive end, there are the flights of flocks of birds visible in the sky in a few scenes, stunningly coordinated and magnificently responsive, wheeling and turning in perfect synchrony. And there is the play of children, illustrated by groups of kids playing a video game, fishing for coins in a storm drain, and seeing how high they can jump. It is as if both groups preserve their freedom by functioning below the corruptions of culture: the birds are part of a system of nature that human culture has not despoiled and the children are too young, innocent, and emotionally open to have yet erected the barriers of self–consciousness and defensiveness that trap their parents.

Wenders imagines only a few openings in this world of walls – a few possibilities of breaking out of the prison of solipsism into forms of personal freedom, connection, and interaction. Two occur at the bottom of the chain of being and two at the top. On the primitive end, there are the flights of flocks of birds visible in the sky in a few scenes, stunningly coordinated and magnificently responsive, wheeling and turning in perfect synchrony. And there is the play of children, illustrated by groups of kids playing a video game, fishing for coins in a storm drain, and seeing how high they can jump. It is as if both groups preserve their freedom by functioning below the corruptions of culture: the birds are part of a system of nature that human culture has not despoiled and the children are too young, innocent, and emotionally open to have yet erected the barriers of self–consciousness and defensiveness that trap their parents.

The other two modes of moving through or across walls – or of leaving them behind – are exemplified by the readers, writers, and researchers at the library and by the angels. The library scenes, filmed at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, one of the city’s most magnificent architectural spaces, give the viewer a visual experience at the opposite remove from the dinginess of the film’s apartments and the confinement of its automobiles. The openness and spaciousness of the interior of the Staatsbibliothek is Wenders’ visual representation of the imaginative expansions of view the library provides. Its books and maps take researchers on journeys that leave worldly walls, boundaries, and barriers behind. Writers and story–tellers (represented by a character named Homer played by veteran actor Curt Bois in his final film performance) navigate seas of time and thought that are blissfully free of the provincialism of national boundaries and the limitations of a merely personal point–of–view. (It’s telling that Wenders includes globes in several of the library scenes, globes that significantly lack markings denoting the divisions of man–made political and ideological boundaries.)

It is no coincidence that the film’s angels use the library as a kind of headquarters and rendezvous point, since the flights of imagination that writers and readers embark on there are the earthly equivalent of what the angels themselves do as spiritual observers. The angels exemplify breathtaking capacities of movement across and beyond all of the earth’s physical and imaginative boundaries. In effect, they unite the different capabilities of birds, children, and thinkers in one identity. They are able to glide through – and see beyond – every earthly imaginative wall, boundary, and separation, bridging gaps and seeing things temporally, spatially, and emotionally whole as no terrestrial inhabitant can – darting, diving, swooping from past to present, from here to there, at the speed of thought.

It is no coincidence that the film’s angels use the library as a kind of headquarters and rendezvous point, since the flights of imagination that writers and readers embark on there are the earthly equivalent of what the angels themselves do as spiritual observers. The angels exemplify breathtaking capacities of movement across and beyond all of the earth’s physical and imaginative boundaries. In effect, they unite the different capabilities of birds, children, and thinkers in one identity. They are able to glide through – and see beyond – every earthly imaginative wall, boundary, and separation, bridging gaps and seeing things temporally, spatially, and emotionally whole as no terrestrial inhabitant can – darting, diving, swooping from past to present, from here to there, at the speed of thought.

But Wenders takes pains to emphasize that there is a deficiency in the angels’ beautiful, free–ranging powers of imaginative sympathy and compassion. Their virtue is that they are detached from the complications and confusions of non–angelic life – that they rise above the corporeality of the body and the mess of the mundane. But that is also their limitation. As Blake puts it in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, they gain certainty and confidence at the expense of replacing the confusion of life with “systematic reasoning.” Damiel, the angel played by Bruno Ganz, summarizes Wenders’ reservations about the limitations of being an angel when he tells angel cohort Cassiel (played by Otto Sandler) that the purity of an imaginative relation to experience is not enough. He longs to experience the mess, opacity, and partiality of the earthbound world. He longs to know what no angel can know: “It would be nice to feed the cat, to get ink from the newspaper on my fingers, to be excited not just by the mind but by a meal…. to feel your bones moving, to live in the now, to guess instead of knowing.” That wish leads Damiel out of the library and away from the streets and into the oddest and most complex imaginative space in the film: the circus where Damiel sees and falls in love with the trapeze artist Marion (played by Wenders’ then–girlfriend Solveig Donmartin).

In a brilliant visual coup de theatre, at the precise point Damiel resolves to give up his state of pure spirituality, Wenders switches the film’s photography from the abstraction of beautifully nuanced black–and–white (representing the angels’ point of view) to the distracting busyness of garishly oversaturated and mismatched color (representing that of humans). Like Dorothy transported to Oz, we and Damiel suddenly realize that we’re not in Kansas anymore.

The visual, social, and imaginative space represented by the circus contrasts in every possible way with the film’s other spaces. Physically, it is open and wallless rather than small and sealed–off like the rooms of the apartment building and the cars on the freeway. But instead of being monumental in scale, solid in its presence, and fixed in its status like the library, this open space is as flimsy and earthy as a tent with a dirt floor. Wenders emphasizes that the tent is not permanent, but is only pitched in a field for a few days and then moved to a new location, assembled and disassembled in an unending cycle of creation and erasure. His point is that the creations of a circus do not have the historical absoluteness and permanence of the masterworks of Western art (in the film’s metaphor, they are not like the works of Homer), but the watery fluidity and evanescence of dramatic performances in front of changing audiences. The connectedness the circus makes, like love–making, only exists for a night. Its meanings are not recorded once and for all for eternity, like those in a book or on a map, but must constantly be made and re–made – like love.

The visual, social, and imaginative space represented by the circus contrasts in every possible way with the film’s other spaces. Physically, it is open and wallless rather than small and sealed–off like the rooms of the apartment building and the cars on the freeway. But instead of being monumental in scale, solid in its presence, and fixed in its status like the library, this open space is as flimsy and earthy as a tent with a dirt floor. Wenders emphasizes that the tent is not permanent, but is only pitched in a field for a few days and then moved to a new location, assembled and disassembled in an unending cycle of creation and erasure. His point is that the creations of a circus do not have the historical absoluteness and permanence of the masterworks of Western art (in the film’s metaphor, they are not like the works of Homer), but the watery fluidity and evanescence of dramatic performances in front of changing audiences. The connectedness the circus makes, like love–making, only exists for a night. Its meanings are not recorded once and for all for eternity, like those in a book or on a map, but must constantly be made and re–made – like love.

As a trapeze artist, Marion is comically positioned as someone who functions suspended between heaven and earth. Like an angel, she does her most creative work above eye–level, but she is also inescapably human in that she is afraid of heights, of the full moon, of losing her job, and of not finding someone to love and be loved by. As a line in the film’s dialogue comically formulates her in–between position, Marion may play an angel in her trapeze act, but she is an angel with chicken–feather wings. In the end, Damiel the angel who wants to descend into the impurity of earthly life, and Marion the non–angel who wants to rise above her state of isolation and loneliness might be said to meet half–way. In the spatial metaphor of the film, each abandons his or her respective perch to move into a middle realm where, rather than rising above, they admit their emotional confusions and doubts – exposing themselves to the pains and uncertainties of a flesh–and–blood relationship.

It is critical that in the scene in which Damiel and Marion finally come together, Marion not only initially resists Damiel’s profession of love and chides him for his half–heartedness, but holds herself at arm’s length from him, delivering a philosophical monologue to him and the viewer (turning out of the dramatic frame and speaking directly to the audience at one point) about separation, loneliness, and the mystery of personal identity. Wenders and screenwriter Peter Handke, whose artistic fingerprints are all over Marion’s speech, avoid the sentimental romantic merging that the ending of City of Angels, the 1998 Hollywood remake with Nicolas Cage and Meg Ryan, indulged in. Mysteries of who and what we are, differences of feeling, the separateness of individuals continue even under the influence of love – but far from being a drawback, Wenders and Handke suggest, that is what makes the earthly world far more interesting than the world of angels – or that of Hollywood movie directors. As Robert Frost wrote, emphasizing the first word, “Earth’s the right place for love. I don’t know where it’s likely to go better.”

It is critical that in the scene in which Damiel and Marion finally come together, Marion not only initially resists Damiel’s profession of love and chides him for his half–heartedness, but holds herself at arm’s length from him, delivering a philosophical monologue to him and the viewer (turning out of the dramatic frame and speaking directly to the audience at one point) about separation, loneliness, and the mystery of personal identity. Wenders and screenwriter Peter Handke, whose artistic fingerprints are all over Marion’s speech, avoid the sentimental romantic merging that the ending of City of Angels, the 1998 Hollywood remake with Nicolas Cage and Meg Ryan, indulged in. Mysteries of who and what we are, differences of feeling, the separateness of individuals continue even under the influence of love – but far from being a drawback, Wenders and Handke suggest, that is what makes the earthly world far more interesting than the world of angels – or that of Hollywood movie directors. As Robert Frost wrote, emphasizing the first word, “Earth’s the right place for love. I don’t know where it’s likely to go better.”

In the largest sense Wings of Desire is a meditation on the function of art. Wenders’ angels are the spirit of filmmaking. As they glide through the world partaking in visions not available to earthbound observers, imaginatively jumping from place to place and time to time, reading people’s minds and expressing their thoughts, they are doing exactly what a camera does and what pieces of film spliced together in a Moviola and the manipulations of dialogue and music on the soundtrack of a movie do in a conventional film. Damiel’s declaration of dissatisfaction with the frictionlessness of his visionary relation to the world is Wenders’ own expression of dissatisfaction with the traditional filmmaker’s idealized relation to his material. Beautiful ideas, pure souls, and exalted spiritual experiences are not enough. The word must be embodied, made flesh, made real. It must be tasted, touched, experienced, and undergone, not merely seen and thought. How can art lower a ladder down into the foul rag and bone shop of the heart and function not as an escape from, but an act of engagement with the flaws, disappointments, and imperfections of the world? How can an artist break down the walls that separate the work from the world and the world from the work?

In the largest sense Wings of Desire is a meditation on the function of art. Wenders’ angels are the spirit of filmmaking. As they glide through the world partaking in visions not available to earthbound observers, imaginatively jumping from place to place and time to time, reading people’s minds and expressing their thoughts, they are doing exactly what a camera does and what pieces of film spliced together in a Moviola and the manipulations of dialogue and music on the soundtrack of a movie do in a conventional film. Damiel’s declaration of dissatisfaction with the frictionlessness of his visionary relation to the world is Wenders’ own expression of dissatisfaction with the traditional filmmaker’s idealized relation to his material. Beautiful ideas, pure souls, and exalted spiritual experiences are not enough. The word must be embodied, made flesh, made real. It must be tasted, touched, experienced, and undergone, not merely seen and thought. How can art lower a ladder down into the foul rag and bone shop of the heart and function not as an escape from, but an act of engagement with the flaws, disappointments, and imperfections of the world? How can an artist break down the walls that separate the work from the world and the world from the work?

Just as Damiel wants to engage himself with the mess and confusion of earthly life, Wenders asks his art to engage itself with forms and forces that are customarily screened out of film. Damiel turns away from the library’s sense of works of art as monuments of unageing intellect and toward the comical, carnivalesque, and performative forms of art represented by the circus. Wenders actually did the same thing in making Wings of Desire. Most of the film’s dialogue was improvised, many of its scenes were created on the spur of the moment, and much of its photography was grabbed. (Wenders was, in fact, so committed to a carnivalesque notion of life and art that his original intention was to end his movie with a pie fight.) Damiel’s fall to earth is an embrace of compromising political, social, and imaginative realities that dovetails with Wenders’ own use of Berlin as a location and his inclusion of painful, personal World War II documentary footage in his narrative. Wings of Desire wants us to question the idealizations, detachments, and purifications that most art relies on. But the questions about the functions of art that Wenders poses won’t be asked or answered theoretically. The work of art is the artist’s way of wrestling with the relation of dreams and realities. And given the state of the contemporary world, the relation of social involvement and imaginative detachment in a work of art is something artists have to grapple with now more than ever.

Ray Carney is professor of film and American studies at Boston University and the author of many books on film and other art. He manages a web site devoted to film, culture, and the function of art at: www.Cassavetes.com.