|

....Cosmo struts through The

Killing of a Chinese Bookie with an aplomb that dozens of gangster

films have immortalized. From Cagney, Raft, Muni, and Bogart in

the forties

to Schwarzenegger, Nicholson, De Niro, and Eastwood in the nineties,

we have seen this he-man maintain his cool under fire as he man-handles

the

women he lets into the margins of his life. But while these films celebrate

masculine coolness and self-possession, Cassavetes wants us to

question

it. Peter Bogdanovich's Saint Jack – which features Ben

Gazzara in a reprise of his role here – succinctly summarizes the

difference: Bogdanovich is in love with his star's charm, panache, and

style, while

Cassavetes

sees them as tragic evasions.

There

are so many extraordinary female parts in Cassavetes' work that it

is easy to forget that he was

one of the supreme explorers of the male psyche in all of American art.

He has Robert Harmon say "men don't interest me," but even

as he says it, his tone gives away his creator's fascination with

the weirdness

of the male psyche. Cassavetes' films put manhood under a microscope – in

all of its various manifestations, from Tony, Bennie, and Hughie in Shadows,

the salesmen in Faces, and the husbands in Husbands,

to Cosmo here, and Robert in Love Streams. The Killing of

a Chinese Bookie is a searching study of what it is to be a man

in our culture. There

are so many extraordinary female parts in Cassavetes' work that it

is easy to forget that he was

one of the supreme explorers of the male psyche in all of American art.

He has Robert Harmon say "men don't interest me," but even

as he says it, his tone gives away his creator's fascination with

the weirdness

of the male psyche. Cassavetes' films put manhood under a microscope – in

all of its various manifestations, from Tony, Bennie, and Hughie in Shadows,

the salesmen in Faces, and the husbands in Husbands,

to Cosmo here, and Robert in Love Streams. The Killing of

a Chinese Bookie is a searching study of what it is to be a man

in our culture.

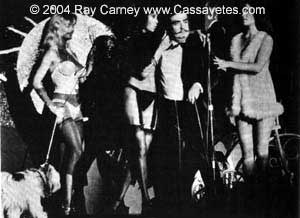

Cassavetes uses Ben Gazzara's

actorly stillness and reserve to investigate the male need to be in

control.

Cosmo is emotionally invulnerable. He won't let anyone – even his

lover Rachel – get past his veneer of poise. He keeps the show

going through thick and thin, in scene after scene. He is stunningly

cool

in the heat

of action and unflappable in the face of death. He devotes his life to

looking good – on stage and off – and succeeds. But Cassavetes

wants us to examine the emotional costs of caring so much about appearances.

He

wants us to ask what happens to our lives when looking good and acting

cool become so important.

Cassavetes' work represents

film as a form of knowledge – as a process of exploring and

understanding people and experiences outside of the movies, but American

film criticism – from

Manny Farber and Andrew Sarris to David Bordwell and beyond – has

never been intensely interested in film as a form of truth-telling.

It is always

easier to describe movies in terms of semantically empty aesthetics (the

"beauty" or "virtuosity" of the photography, the "signature

of the auteur" or the "stylistics" of the work);

to talk about a movie's relation to other movies (its conformity to

or violation

of "genre conventions," its "intertextual" connections

with other films); to describe it in terms of contentless cognitive

arrangements

(value-neutral "structures" of meaning and emotionally empty

"diegetic strategies"); or to reduce it to a series of de-authored,

impersonal "ideological" predispositions (as much feminist

and politically engaged criticism does). Such criticism unconsciously

internalizes

the values of Hollywood filmmaking (the values it is supposed to place

in critical perspective). It parades its knowledge of lighting, photography,

and editing, but has virtually nothing to tell us about life or the relation

of art to life. Like the typical high-concept pitch session, it is

keen

on connections of one movie with another, but falls silent if we dare

to ask why any of this matters.

Since the explorations in Cassavetes'

films never remain merely formal, since his style is always in service

of moral values and human meanings, his work raises issues with which

such criticism simply cannot deal. His films explore new human emotions,

new conceptions of personality, new possibilities of social relationship.

He explores new ways of being in the world, not merely new formal "moves."

His films are not walled off in an artistic never-never land of stylistic

inbreeding and cross-referencing. Cassavetes gives us films that tell

us about life, and aspire to help us to live it. He shows us that art

can be a form of knowledge, the finest, most complex form of knowledge,

and of its communication, yet invented. We learn things when we watch

his movies, about our culture, ourselves, and our relations with others,

that we never knew and that can't be communicated in any other way. This

passed relatively unnoticed and uncommented upon during his lifetime because

the knowledge we acquire is not didactic, but stylistic. We don't learn

new facts or observations or beliefs, but new ways of seeing, hearing,

thinking, feeling, and being in the world. Since the explorations in Cassavetes'

films never remain merely formal, since his style is always in service

of moral values and human meanings, his work raises issues with which

such criticism simply cannot deal. His films explore new human emotions,

new conceptions of personality, new possibilities of social relationship.

He explores new ways of being in the world, not merely new formal "moves."

His films are not walled off in an artistic never-never land of stylistic

inbreeding and cross-referencing. Cassavetes gives us films that tell

us about life, and aspire to help us to live it. He shows us that art

can be a form of knowledge, the finest, most complex form of knowledge,

and of its communication, yet invented. We learn things when we watch

his movies, about our culture, ourselves, and our relations with others,

that we never knew and that can't be communicated in any other way. This

passed relatively unnoticed and uncommented upon during his lifetime because

the knowledge we acquire is not didactic, but stylistic. We don't learn

new facts or observations or beliefs, but new ways of seeing, hearing,

thinking, feeling, and being in the world.

The

experiences in Cassavetes' films were mysterious to him and his actors

when he began them, while he made them, and after he was finished with

them, and they stay mysterious for a viewer, no matter how many times

he sees the films. The mysteriousness is the experience itself; it is

not something added to it in the writing, shooting, editing process, nor

is it something eventually to be gotten beyond by figuring it out. As

in a Charlie Parker performance, the experience Cassavetes presents only

exists in all its speed and density; it never existed in outline form

and can therefore never be subsequently translated into outline form,

so it stays complex no matter how many times we have it. It may take from

three to five viewings of a particular work to get the hang of it, but

even when that happens, the complexity is not something we leave behind.

Mastery doesn't involving rising above the soupiness, the opacity, the

uncertainty, but rather learning to live in them, responding nimbly

enough to stay with them, not to drop out of them for even a second. As

in listening to the best of Dizzy Gillespie or watching Balanchine's Symphony

in Three Movements, it's when we haven't mastered the experience that

we keep dropping out of it in a quest for simplifying essences, origins,

destinations, or resolutions. Understanding Cassavetes does not consist

of moving from confusion to clarity, from thickness to thinness, but rather

of eventually learning how to live with particularly intricate and interesting

forms of uncertainty, weight, and clutter. The

experiences in Cassavetes' films were mysterious to him and his actors

when he began them, while he made them, and after he was finished with

them, and they stay mysterious for a viewer, no matter how many times

he sees the films. The mysteriousness is the experience itself; it is

not something added to it in the writing, shooting, editing process, nor

is it something eventually to be gotten beyond by figuring it out. As

in a Charlie Parker performance, the experience Cassavetes presents only

exists in all its speed and density; it never existed in outline form

and can therefore never be subsequently translated into outline form,

so it stays complex no matter how many times we have it. It may take from

three to five viewings of a particular work to get the hang of it, but

even when that happens, the complexity is not something we leave behind.

Mastery doesn't involving rising above the soupiness, the opacity, the

uncertainty, but rather learning to live in them, responding nimbly

enough to stay with them, not to drop out of them for even a second. As

in listening to the best of Dizzy Gillespie or watching Balanchine's Symphony

in Three Movements, it's when we haven't mastered the experience that

we keep dropping out of it in a quest for simplifying essences, origins,

destinations, or resolutions. Understanding Cassavetes does not consist

of moving from confusion to clarity, from thickness to thinness, but rather

of eventually learning how to live with particularly intricate and interesting

forms of uncertainty, weight, and clutter.

Cassavetes'

procedures were the furthest thing imaginable from following a blueprint.

His cameramen, producers, and actors all tell stories about how many different

ways he wrote, rehearsed, shot, and cut his films, continuously rethinking

the material. He was always ready to change in order to pursue a discovery.

If he shot a scene and noticed something unexpected that interested him

along the way, he might change everything to pursue it. Since he filmed

in continuity, as he worked, he was truly watching and wondering, studying

and learning about his scenes and his characters. As an example, Cosmo's

meeting with the gangsters in the casino after his night gambling was

shot over and over again with Gazzara "thanking" the gangsters

for their kindness to him using almost imperceptibly different tones of

voice, gestures, and facial expressions. Cassavetes later said that he

regarded this as one of the key moments in the film, and wanted to understand

how someone like Cosmo could carry off the experience of losing absolutely

everything while still holding onto his self-respect. He wanted to understand

what kind of person can "thank" someone for ruining his life.

As he was editing, he repeated the process: comparing alternate takes,

studying the unplanned gestures or spontaneous expressions that might

have unexpectedly surfaced in a particular take for what they might mean

or reveal, playing with the footage to shift the tone or change the emotional

effect slightly.... Cassavetes'

procedures were the furthest thing imaginable from following a blueprint.

His cameramen, producers, and actors all tell stories about how many different

ways he wrote, rehearsed, shot, and cut his films, continuously rethinking

the material. He was always ready to change in order to pursue a discovery.

If he shot a scene and noticed something unexpected that interested him

along the way, he might change everything to pursue it. Since he filmed

in continuity, as he worked, he was truly watching and wondering, studying

and learning about his scenes and his characters. As an example, Cosmo's

meeting with the gangsters in the casino after his night gambling was

shot over and over again with Gazzara "thanking" the gangsters

for their kindness to him using almost imperceptibly different tones of

voice, gestures, and facial expressions. Cassavetes later said that he

regarded this as one of the key moments in the film, and wanted to understand

how someone like Cosmo could carry off the experience of losing absolutely

everything while still holding onto his self-respect. He wanted to understand

what kind of person can "thank" someone for ruining his life.

As he was editing, he repeated the process: comparing alternate takes,

studying the unplanned gestures or spontaneous expressions that might

have unexpectedly surfaced in a particular take for what they might mean

or reveal, playing with the footage to shift the tone or change the emotional

effect slightly....

This page only

contains excerpts and selected passages from Ray Carney's writing about

John Cassavetes. To obtain the complete text as well as the complete texts

of many pieces about Cassavetes that are not included on the web site,

click

here.

|

I

won't call [my work] entertainment. It's exploring. It's asking questions

of people, constantly: How much do you feel? How much do you know? Are

you aware of this? Can you cope with this? A good movie will ask you

questions

you haven't been asked before, ones that you haven't thought about every

day of your life. Or, if you have thought about them, you haven't

had the

questions posed this way. [Film is an investigation of life.] What we are.

What our responsibilities in life are – if any. What we are

looking for; what problems do you have that I may have? What part

of life are we both

interested in knowing more about?

I

won't call [my work] entertainment. It's exploring. It's asking questions

of people, constantly: How much do you feel? How much do you know? Are

you aware of this? Can you cope with this? A good movie will ask you

questions

you haven't been asked before, ones that you haven't thought about every

day of your life. Or, if you have thought about them, you haven't

had the

questions posed this way. [Film is an investigation of life.] What we are.

What our responsibilities in life are – if any. What we are

looking for; what problems do you have that I may have? What part

of life are we both

interested in knowing more about?

There

are so many extraordinary female parts in Cassavetes' work that it

is easy to forget that he was

one of the supreme explorers of the male psyche in all of American art.

He has Robert Harmon say "men don't interest me," but even

as he says it, his tone gives away his creator's fascination with

the weirdness

of the male psyche. Cassavetes' films put manhood under a microscope – in

all of its various manifestations, from Tony, Bennie, and Hughie in Shadows,

the salesmen in Faces, and the husbands in Husbands,

to Cosmo here, and Robert in Love Streams. The Killing of

a Chinese Bookie is a searching study of what it is to be a man

in our culture.

There

are so many extraordinary female parts in Cassavetes' work that it

is easy to forget that he was

one of the supreme explorers of the male psyche in all of American art.

He has Robert Harmon say "men don't interest me," but even

as he says it, his tone gives away his creator's fascination with

the weirdness

of the male psyche. Cassavetes' films put manhood under a microscope – in

all of its various manifestations, from Tony, Bennie, and Hughie in Shadows,

the salesmen in Faces, and the husbands in Husbands,

to Cosmo here, and Robert in Love Streams. The Killing of

a Chinese Bookie is a searching study of what it is to be a man

in our culture. Since the explorations in Cassavetes'

films never remain merely formal, since his style is always in service

of moral values and human meanings, his work raises issues with which

such criticism simply cannot deal. His films explore new human emotions,

new conceptions of personality, new possibilities of social relationship.

He explores new ways of being in the world, not merely new formal "moves."

His films are not walled off in an artistic never-never land of stylistic

inbreeding and cross-referencing. Cassavetes gives us films that tell

us about life, and aspire to help us to live it. He shows us that art

can be a form of knowledge, the finest, most complex form of knowledge,

and of its communication, yet invented. We learn things when we watch

his movies, about our culture, ourselves, and our relations with others,

that we never knew and that can't be communicated in any other way. This

passed relatively unnoticed and uncommented upon during his lifetime because

the knowledge we acquire is not didactic, but stylistic. We don't learn

new facts or observations or beliefs, but new ways of seeing, hearing,

thinking, feeling, and being in the world.

Since the explorations in Cassavetes'

films never remain merely formal, since his style is always in service

of moral values and human meanings, his work raises issues with which

such criticism simply cannot deal. His films explore new human emotions,

new conceptions of personality, new possibilities of social relationship.

He explores new ways of being in the world, not merely new formal "moves."

His films are not walled off in an artistic never-never land of stylistic

inbreeding and cross-referencing. Cassavetes gives us films that tell

us about life, and aspire to help us to live it. He shows us that art

can be a form of knowledge, the finest, most complex form of knowledge,

and of its communication, yet invented. We learn things when we watch

his movies, about our culture, ourselves, and our relations with others,

that we never knew and that can't be communicated in any other way. This

passed relatively unnoticed and uncommented upon during his lifetime because

the knowledge we acquire is not didactic, but stylistic. We don't learn

new facts or observations or beliefs, but new ways of seeing, hearing,

thinking, feeling, and being in the world. The

experiences in Cassavetes' films were mysterious to him and his actors

when he began them, while he made them, and after he was finished with

them, and they stay mysterious for a viewer, no matter how many times

he sees the films. The mysteriousness is the experience itself; it is

not something added to it in the writing, shooting, editing process, nor

is it something eventually to be gotten beyond by figuring it out. As

in a Charlie Parker performance, the experience Cassavetes presents only

exists in all its speed and density; it never existed in outline form

and can therefore never be subsequently translated into outline form,

so it stays complex no matter how many times we have it. It may take from

three to five viewings of a particular work to get the hang of it, but

even when that happens, the complexity is not something we leave behind.

Mastery doesn't involving rising above the soupiness, the opacity, the

uncertainty, but rather learning to live in them, responding nimbly

enough to stay with them, not to drop out of them for even a second. As

in listening to the best of Dizzy Gillespie or watching Balanchine's Symphony

in Three Movements, it's when we haven't mastered the experience that

we keep dropping out of it in a quest for simplifying essences, origins,

destinations, or resolutions. Understanding Cassavetes does not consist

of moving from confusion to clarity, from thickness to thinness, but rather

of eventually learning how to live with particularly intricate and interesting

forms of uncertainty, weight, and clutter.

The

experiences in Cassavetes' films were mysterious to him and his actors

when he began them, while he made them, and after he was finished with

them, and they stay mysterious for a viewer, no matter how many times

he sees the films. The mysteriousness is the experience itself; it is

not something added to it in the writing, shooting, editing process, nor

is it something eventually to be gotten beyond by figuring it out. As

in a Charlie Parker performance, the experience Cassavetes presents only

exists in all its speed and density; it never existed in outline form

and can therefore never be subsequently translated into outline form,

so it stays complex no matter how many times we have it. It may take from

three to five viewings of a particular work to get the hang of it, but

even when that happens, the complexity is not something we leave behind.

Mastery doesn't involving rising above the soupiness, the opacity, the

uncertainty, but rather learning to live in them, responding nimbly

enough to stay with them, not to drop out of them for even a second. As

in listening to the best of Dizzy Gillespie or watching Balanchine's Symphony

in Three Movements, it's when we haven't mastered the experience that

we keep dropping out of it in a quest for simplifying essences, origins,

destinations, or resolutions. Understanding Cassavetes does not consist

of moving from confusion to clarity, from thickness to thinness, but rather

of eventually learning how to live with particularly intricate and interesting

forms of uncertainty, weight, and clutter. Cassavetes'

procedures were the furthest thing imaginable from following a blueprint.

His cameramen, producers, and actors all tell stories about how many different

ways he wrote, rehearsed, shot, and cut his films, continuously rethinking

the material. He was always ready to change in order to pursue a discovery.

If he shot a scene and noticed something unexpected that interested him

along the way, he might change everything to pursue it. Since he filmed

in continuity, as he worked, he was truly watching and wondering, studying

and learning about his scenes and his characters. As an example, Cosmo's

meeting with the gangsters in the casino after his night gambling was

shot over and over again with Gazzara "thanking" the gangsters

for their kindness to him using almost imperceptibly different tones of

voice, gestures, and facial expressions. Cassavetes later said that he

regarded this as one of the key moments in the film, and wanted to understand

how someone like Cosmo could carry off the experience of losing absolutely

everything while still holding onto his self-respect. He wanted to understand

what kind of person can "thank" someone for ruining his life.

As he was editing, he repeated the process: comparing alternate takes,

studying the unplanned gestures or spontaneous expressions that might

have unexpectedly surfaced in a particular take for what they might mean

or reveal, playing with the footage to shift the tone or change the emotional

effect slightly....

Cassavetes'

procedures were the furthest thing imaginable from following a blueprint.

His cameramen, producers, and actors all tell stories about how many different

ways he wrote, rehearsed, shot, and cut his films, continuously rethinking

the material. He was always ready to change in order to pursue a discovery.

If he shot a scene and noticed something unexpected that interested him

along the way, he might change everything to pursue it. Since he filmed

in continuity, as he worked, he was truly watching and wondering, studying

and learning about his scenes and his characters. As an example, Cosmo's

meeting with the gangsters in the casino after his night gambling was

shot over and over again with Gazzara "thanking" the gangsters

for their kindness to him using almost imperceptibly different tones of

voice, gestures, and facial expressions. Cassavetes later said that he

regarded this as one of the key moments in the film, and wanted to understand

how someone like Cosmo could carry off the experience of losing absolutely

everything while still holding onto his self-respect. He wanted to understand

what kind of person can "thank" someone for ruining his life.

As he was editing, he repeated the process: comparing alternate takes,

studying the unplanned gestures or spontaneous expressions that might

have unexpectedly surfaced in a particular take for what they might mean

or reveal, playing with the footage to shift the tone or change the emotional

effect slightly....