Biographies

Biography by Lauren Hippert

Hannah Tillich (May 19, 1896- October 27, 1988)

Hannah Tillich, named Johanna Werner at birth, was born in Rothenburg, Germany on May 19, 1896. After graduating from high school, she attended the King's School of Art to obtain a teaching degree. [1] Following the King's School, she taught in a school managed by her father [2] until her first marriage to Albert Gottschow in 1920. Two years later, they divorced and Hannah married Paul Tillich in 1924. They remained married until his death in 1965; after his death, Hannah never remarried.

They first lived in Berlin where Paul was serving as a privatdozent in theology at the University of Berlin. They moved to Marburg when Paul received an appointment to an assistant professorship in theology at the University of Marburg. It was during his later appointment at the University of Frankfurt, however, that Paul aroused the suspicion of the authorities by speaking out publicly against the Nazi regime, anti-semitism, and excessive nationalism. Tillich was suspended from his positions, and his mail began to be censored. [3] In order to protect themselves, their families, and friends who remained in Germany working underground, they along with their daughter emigrated to the United States in 1933. Hannah was both forceful and adamant that their safest option was to leave Germany. She specifically refused to subject their daughter, Erdmuthe, to a Nazi education.[4]

After their immigration to the United States, Paul became a professor at Union Theological Seminary in Manhattan. He also became extremely active in an organization designed to assist other European refugees to the United States - “Self-Help for Emigres from Central Europe.” [5] His unceasing efforts to help refugees was a source of strife between Hannah and him because Hannah felt that he was abandoning his own family in the refugees' favor. She recalled in her first memoir, “It was easier for a student in trouble to see him than for one of his children or his wife. Home life was irritating.” [6] Paul also refused to accept payment compensation for the lectures he was invited to give at other universities. Impoverished as the family was at the time, this also placed a great deal of strain on their marriage.

Another source of tension and distress for Hannah is that she and Paul had what would now be called an open marriage, though she does not label it as such in her memoir. She records terrible fits of jealousy [7] and feelings of betrayal [8], even though she also had extramarital affairs of her own. In spite of all of these setbacks, in her later life, her relationship with Paul improved. “Whatever had been alive in our relationship in our young days had stayed alive after sex reached its denouement” she reflected. [9] Shortly before Paul Tillich died in 1965, he accepted a position with the New School for Social Research in New York. [10] Hannah remained in East Hampton until her death in 1988.[11]

In her later life, after Paul Tillich's death, Hannah wrote two memoirs: “From Time to Time,” published in 1973; and “From Place to Place: Travels with Paul Tillich, Travels without Paul Tillich,” published in 1976. “From Time to Time” describes her early life, the struggles she and her family went through in World War I, her tumultuous marriage to Paul Tillich, their emigration to the United States, their life together, and his death. Most notably her first memoir, Hannah's publishings have brought about the most significant aspects of her legacy. While her second memoir presented a more mild tone, readers were shocked at what they had read in the first installment called From Time To Time. While much had been published about Paul Tillich's theology and life, From Time to Time was the first work in which someone described Tillich's sexual exploits to the public. [12] Hannah's unapologetic account of her late husbands lifestyle left many troubled especially when it came to sexuality. For example she writes about Paul's preoccupation with sadism and pornogrophy.calling them “obsene signs of the real life that he [Paul] had transformed into the gold of abstraction: king Midas of the spirit.” [13] Tillich himself never publicly mentioned his extramarital affairs nor his unique sexual appetites. The memoir was released after his death and he was not able to defend himself. Many have gone to great lengths to discredit aspects of Hannah Tillich's portrayal of her late husband's life by focusing on her bias or her emotional state when she authored her writing. Since the initial publishing of From Time to Time, however, there have been numerous stories which confirm much of what Hannah had claimed of Paul. One such example detailed in a biography of Reinhold Niebuhr explains how he had sent a female student to Tillich's office hours for consultation where Tillich proseeded to make unwanted sexaul advances on the student. Niebuhr never forgave Tillich for his indiscretions but never made these things public. If it were not for her memoir, the wider world may not have discovered Tillich's secrets for decades to come. Hannah's side of the story sheds Paul Tillich's story in a new light--for this reason, her first memoir From Time to Time is best known of her works. [14] In addition to the works mentioned above, she also wrote poetry and published a novel called “Harbor Mouse” in 1978. In reference to this novel, she exclaimed in an interview, “I have absolutely decided to finish the book on which I am writing. I am not going to die before that.” [15] In fact, she went on to live 12 years after its publication, and 23 years after the death of Paul Tillich.

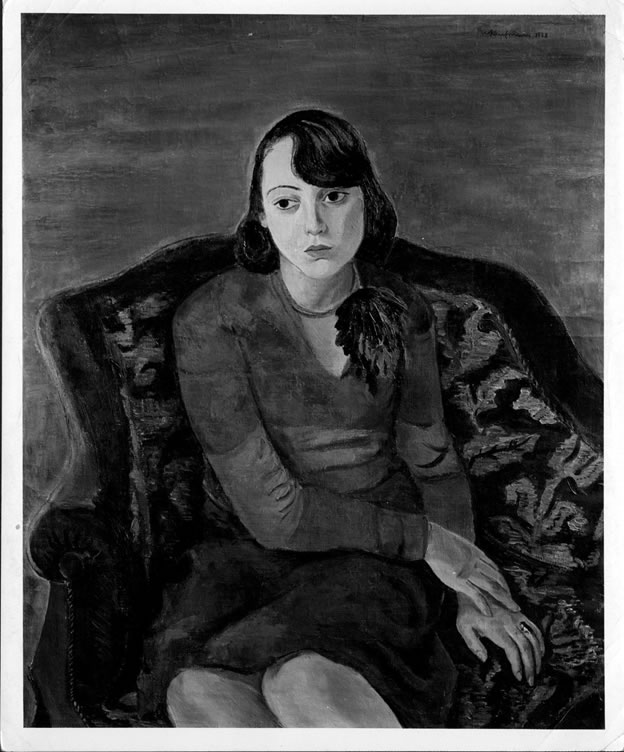

A portrait of Hannah Tillich in the 1930's. Box 238 Folder 5. Paul Tillich Archives at Harvard.

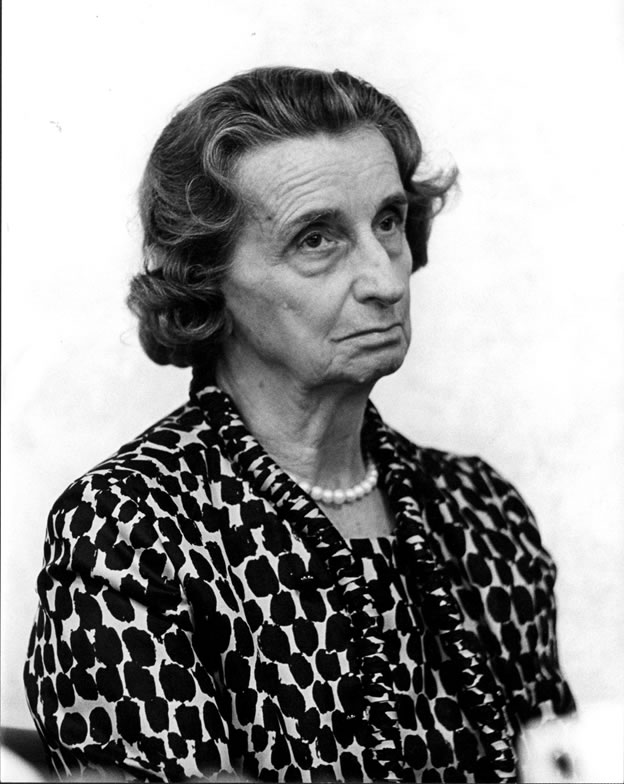

A photograph of Hannah Tillich in April 1965. Box 238 Folder 28 at Harvard Paul Tillich Archives.

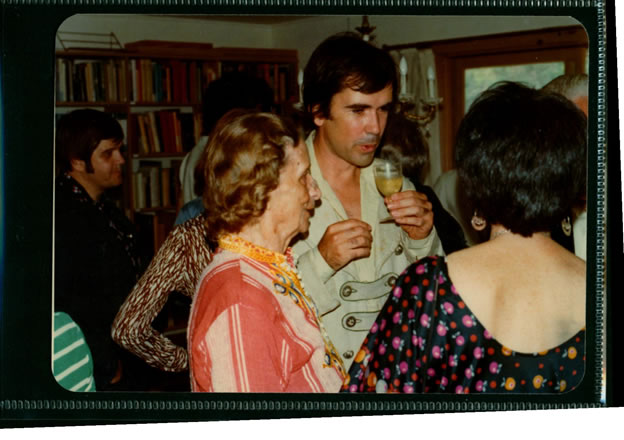

Hannah Tillich at her 80th birthday party. Box 721 folder 6 at the Harvard Paul Tillich Archives.

Hannah Tillich at her 80th birthday party. Box 721 folder 6 at the Harvard Paul Tillich Archives.

Hannah Tillich at her 80th birthday party. Box 721 folder 6 at the Harvard Paul Tillich Archives.

Notes

[1]

Tillich, Hannah. From Time to Time. New York: Stein and Day Publishers, 1973, 61.

[3] Pauck, Wilhelm & Marion Pauck. Paul Tillich: His Life & Thought. Glasgow: William Collins Sons & Co, Ltd, 1976, 131.

[11]

Saxon, Wolfgang. “Hannah Tillich, 92, Christian Theologian's Widow.” New York Times. URL: http://www.nytimes.com/1988/10/30/obituaries/hannah-tillich-92-christian-theologian-s-widow.html Accessed October 2015.

[12] Fessenden, Tracy, “‘Women’ and the ‘Primitive’ Paul Tillich's Life and Thought: Some Implications for the Study of Religion,” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, 14 no. 2 (Fall 1998), 47.

[15] Wedemeyer, Dee. “A Colloquium of Intelligentsia: An Intellectual Gaggle.” New York Times. May 23, 1976.

Bibliography

Fessenden, Tracy. “‘Women’ and the ‘Primitive’ Paul Tillich's Life and Thought: Some Implications for the Study of Religion.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, 14 no. 2 Fall 1998, 45-76.

Pauck, Wilhelm & Marion Pauck. Paul Tillich: His Life & Thought. Glasgow: William Collins Sons & Co, Ltd, 1976.

Saxon, Wolfgang. “Hannah Tillich, 92, Christian Theologian's Widow.” New York Times. URL: http://www.nytimes.com/1988/10/30/obituaries/hannah-tillich-92-christian-theologian-s-widow.html Accessed October 2015.

Tillich, Hannah. From Time to Time. New York: Stein and Day Publishers, 1973.

Tillich, Hannah. Papers, 1896-1976. Andover-Harvard Theological Library. URL:

http://oasis.lib.harvard.edu/oasis/deliver/deepLink?_collection=oasis&uniqueId=div00721

Accessed October 2015.

Wedemeyer, Dee. “A Colloquium of Intelligentsia: An Intellectual Gaggle.” New York Times. May 23, 1976.

The information on this page is copyright ©1994 onwards, Wesley

Wildman (basic information here), unless otherwise

noted. If you want to use text or ideas that you find here, please be careful to acknowledge this site as

your source, and remember also to credit the original author of what you use,

where that is applicable. If you have corrections or want to make comments,

please contact me at the feedback address for permission.

|