Theodicy--through the Case of “Unit 731”

By Eun Park, December 2003

This work is about how far humans can go in their cruelty. It is about what can be the driving force for human cruelty. It is about how God could possibly create humans such terrible way. It is about whether God has created a certain uncontrollable and malicious driving force of human viciousness outside humanity—Evil. This work is, therefore, about how we should think of God’s justice and infallibleness—Theodicy.

Soldiers impaled babies on bayonets and tossed them still alive into pots of boiling water… They gang-raped women from the ages of 12 to 80 and then killed them when they could no longer satisfy sexual requirements (The Other Holocaust: Nanjing Massacre, Unit 731, Unit 100, Unit 516, http://www.skycitygallery.com/japan/japan.html, p.13)

After infecting him, the researchers decided to cut him open alive, tear him apart, organ by organ, to see what the disease does to a man’s inside. Often no anesthetic was used… out of concern that it might have an effect on the results (Ibid, p.2).

I preserved a lot of human lab specimens in Formalin. Some were heads, others were arms, legs, internal organs, and some were entire bodies. There were large numbers of these jars lined up, even specimens of children and babies (Hal Gold, Unit 731 Testimony, Yenbooks: Singapore, 1996, p.169).

There was a Chinese woman in there who had been used in a frostbite experiment. She had several fingers missing and her bones were black, with gangrene set in… He was about to rape her anyway, then he saw that her sex organ was festering, with pus oozing to the surface. He gave up the idea, left, and locked the door, then later went on to his experimental work (Ibid, pp. 165-166).

I. CASE REPORT—

Unit 731: Japanese Human Slaughter for Bio-Warfare

The above citations are from testimonies of Japanese massacre in Manchuria, and human experiments to develop bio-weapons during the Second World War. The human experiments were mainly held in a secret military unit called “Unit 731,” or the “Ishii Unit,” and several other associate units in Manchuria. Since the Japanese government has so carefully tried to eliminate all physical evidence related to these experiments, research regarding this case is heavily dependent on testimonies mainly from Japanese who had formerly worked at Unit 731 and the associated units during the war time.

The

chief of Unit 731, Shiro Ishii, was born on June 25th, 1892, in a rich

family. He grew tall and smart. “He was an individualist, his demeanor

indicating high determination and arrogance” (Williams & Wallas 1989:

7). Ishii studied medicine at Kyoto Imperial University, and voluntarily

joined the Imperial Guards as an army surgeon. Later in the late nineteen

twenties, Ishii started to persuade some Japanese military authorities to

develop biological weapons, insisting the massive killing power of

epidemics. After Japan occupied Manchuria in 1931, Ishii, with the support

of his patron Nagata, chief of the Military Affairs Section of the

powerful Military Affairs Bureau at that time, started human experiments

in Manchuria. In 1935, he established his first military laboratory, Togo

Unit, outside Harbin, the capital of Manchuria. The Togo Unit received the

notorious new name ‘Unit 731’ the following year. Later, with the

approval of Emperor Hirohito, Ishii established a new laboratory building

exclusively for human experiments which had taken longer than two years (5-35).

The atmosphere of the new human experimental laboratory was the following:

The

chief of Unit 731, Shiro Ishii, was born on June 25th, 1892, in a rich

family. He grew tall and smart. “He was an individualist, his demeanor

indicating high determination and arrogance” (Williams & Wallas 1989:

7). Ishii studied medicine at Kyoto Imperial University, and voluntarily

joined the Imperial Guards as an army surgeon. Later in the late nineteen

twenties, Ishii started to persuade some Japanese military authorities to

develop biological weapons, insisting the massive killing power of

epidemics. After Japan occupied Manchuria in 1931, Ishii, with the support

of his patron Nagata, chief of the Military Affairs Section of the

powerful Military Affairs Bureau at that time, started human experiments

in Manchuria. In 1935, he established his first military laboratory, Togo

Unit, outside Harbin, the capital of Manchuria. The Togo Unit received the

notorious new name ‘Unit 731’ the following year. Later, with the

approval of Emperor Hirohito, Ishii established a new laboratory building

exclusively for human experiments which had taken longer than two years (5-35).

The atmosphere of the new human experimental laboratory was the following:

Hidden from the outside world at the center of Unit 731’s Ro block was Ishii’s ‘secret of secrets’. So carefully was its existence kept secret that many junior members of Unit 731 had no knowledge that it was there at all (Ibid, p.31).

Through the spyhole cut in the steel doors of each cell, the plight of the chained marutas [Japanese word meaning ‘logs,’ human guinea-pigs: writer’s note] could be seen. Some had rotting limbs, bits of bone protruding through skin blackened by necrosis. Others were sweating in high fever, writhing in agony or mourning in pain. Those who suffered from respiratory infections coughed incessantly. Some were bloated, some emaciated, and others were blistered or had open wounds… Through the little spyholes the most acute symptoms of the worst dieses in the world were coldly observed by 731’s white-coated doctors (Ibid, pp. 36-37).

In this new laboratory, and in another associated unit, Unit 100, research squads experimented on epidemics using marutas such as bubonic plague, anthrax, smallpox, typhoid, paratyphoid, tularemia, cholera, epidemic hemorrhagic fever, syphilis, aerosols, botulism, brucellosis, dysentery, tetanus, glanders, tuberculosis, yellow fever, typhus, tularemia, gas gangrene, scarlet sever, songo, diphtheria, erysipelas, salmonella, venereal diseases, infectious jaundice, undulant fever, epidemic cerebrospinal meningitis, tick encephalitis, plant diseases for crop destruction, and other epidemics (The Other Holocaust, pp.2-3). Hiroshi Matsumoto, a former medic, testified about the situation of the units as the following:

There were seven cages in each of several rooms. The cages were only big enough for one naked Chinese to sit cross-legged. Unit members injected the prisoners with a variety of bacteria and observed them for three or four months. Blood samples were then taken from the prisoners and they were killed. The cages were seldom empty (News Watch, http://www.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/NanjingMassacre/Watch.html, 4).

About how Japanese researchers treated their marutas, there is a testimony to the following:

In order to obtain accurate data from dissection, researchers wanted to have the matura in as normal a state as possible… some were tied down and cut open while fully conscious. At first the matura would let out a hideous scream, but soon the voice would stop. The organs would be compared with healthy conditions, and then the organs would be preserved (H. Gold, Ibid, p.170).

Another associated unit of Unit 731, Unit 1644, had cells that could keep maturas and experimental animals such as rats together. An anonymous testimony reads:

…the room was about ten by fifteen meters with cages all in a raw. Most of the maruta in the cages were just lying down. In the same room were oil cans with mice that had been injected with plague germs, and with fleas feeding on the mice. There were not the usual types of fleas, but a transparent variety. Around the perimeter of the room was a thirty-centimeter-wide trough of running water [The purpose of the trough, which is wider than the distance over which the fleas can leap, is apparently to keep the fleas from going outside the room: author’s note] (Ibid, pp.151-152).

A team of doctors dissects a victim; one member weighs

organs removed from the body.

Replica of experiments displayed at the Unit 731 exhibition (Ibid, p.133)

Human experiments were not object to just adult marutas. Researchers in Unit 731 also used infants for their experiments. A report from China testifies that researchers in Unit 731 also ‘used’ infants and babies born to pregnant prisoners and to those who had made pregnant through forced sex in venereal disease experiments (Ibid, p.165).

Not only did Ishii’s squads experiment to spread epidemics, but they also did experiments to develop cures for Japanese soldiers during the Second World War. To find a cure for syphilis prevailing among Japanese soldiers due to their arbitrary rape of civilians and sexual intercourses with comfort women, a squad of Ishii did an experiment described as the following:

Infection of venereal disease by injection was abandoned… A male and female, one infected with syphilis, would be brought together in a cell and forced into sex with each other. It was made clear that anyone resisting would be shot. Once the healthy partner was infected, the progress of the disease would be observed closely to determine for example how far it advanced the first week, the second week, and so forth. Instead of merely looking at external signs, such as the condition of the sexual organs, researchers were able to employ live dissection to investigate how different internal organs are affected at different stages of the disease (Ibid, p.164).

Doing this experiment, they killed many female marutas. On one occasion, they intentionally infected a pregnant woman with syphilis, and dissected both the mother and the baby after the baby was born (William & Wallace, Ibid, p. 41).

They also did experiments to find cure for frostbite which was common among the soldiers. Testimonies regarding this experiment say the following:

Yoshimura Hisato, who later became head of the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, was in charge of frostbite experiments. He was known as an outstanding scholar and researcher. One of his experiments was with a three-month-old baby. A temperature-sensing needle was injected into the baby’s hand and the infant was immersed in ice water, and the temperature changes were carefully recorded. After the war he issued a paper on this experiment and the results (Ibid, p.165).

Two naked men were put in an area 40-50 degrees below zero and researchers filmed the whole process until they died. They suffered such agony they were digging their nails into each other’s flesh (Williams & Wallace, Ibid, p.44).

After finishing their experiments, they burned dead marutas in the unit. “There was a big smokestack in the unit. On some days it poured smoke, sometimes there was none. It was far from our barracks. Once, we asked what was burning. The answer was ‘prisoners’” (H. Gold, Ibid, p.181).

Part of the remained Unit 731 Complex (H. Gold, Ibid,

p.129)

Some say over three thousand people, mainly Chinese (around seventy percent: Williams & Wallace, Ibid, p.35) and also Russians and Koreans, were killed and burned in Unit 731 and other associated units (Ibid, p.49). Others say more than ten thousands were used as ‘maturas’ and killed (The Other Holocaust, p.3-4).

The Japanese, of course, used the results of their human experiments during the war. Countless Manchurians were killed from diverse plagues. “Plague-infected fleas were dropped by bomb…,” “Some researchers say as many as two hundred thousands of Chinese died from plagues and other diseases produced in the laboratories of Unit 731” (News Watch, p.13). Chapter six of Unit 731 by William and Wallace is all about this biological warfare done by the Japanese army and its cost (pp. 63-80). A Chinese doctor, Qui Mingxuan, talks about the effect of the bio-warfare in current times: “After 60 years, we are still finding positive antibodies of bubonic plagues in rats, dogs, cats, and other animals. Every year a certain number of healthy people develop typhoid. Japan’s germ warfare has left behind problems that still threaten our lives” (The Other Holocaust, p.7). It is estimated that more than three and a half million Chinese were killed from slaughters and plagues by the Japanese in Manchuria during 1937 to 1945 (News Watch, p.10).

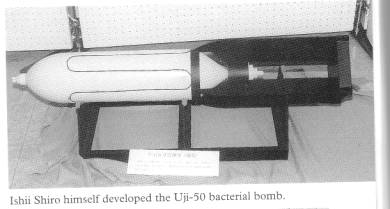

Ishii himself

developed the bacterial bomb (H. Gold, Ibid, p.131)

Japanese human experiments did not stop as the war ended. It is reported that after the Second World War, these experiments were continued by Japan and the USA, for example, during the Korean War, and the bacterial warfare methods were used by the US troops during the war. A testimony regarding the negotiation between Japan and the USA is the following:

There was also an interview with retired Lt. Col. Murray Sanders, the first US investigator into Unit 731. Sanders claimed that General Douglas MacArthur authorized him to make a deal with the Japanese if they cooperated with the US Biological Warfare Scientist (Ibid, p.5).

Former researchers of Ishii’s unit went to Korea, and continued their experiments. “They were taken to Korea because America used BW and was unable to protect its own army… The research in Korea included not just animals but human dissection” (H. Gold, Ibid, p.173). Although it will not be mentioned any further here because it is outside the main case of this work, chapter seventeen of Unit 731—the Japanese Army’s Secret of Secrets deals with this matter in detail under the title of “Korean War” (pp. 235-285).

How could this collective human behavior, too malicious to be true, be possible? How can we humans understand this collective viciousness of humanity? Sociologists C. Wright Mills gives us an analytical tool through which we can understand this terrible happening in humanity in larger scope with historical viewpoints.

II.CASE ANALYSIS:

SOCIO-HISTORICAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS

--the Accumulated Human Malignity

C. Wright Mills writes in his Sociological Imagination (Oxford University Press: New York, 1959) that we are required to have sociological imagination which allows us to have the capacity to understand any individual or single-case happening through one’s or its current social context and the whole human history. This is required for the future well-being of the entire humanity because only holistic understanding of human affairs let humanity prepare better future. In this regard, any understanding lack of holistic socio-historical viewpoints is considered human ignorance (pp. 3-24).

Based on the above framework, one may see Unit 731’s human experiments for bio-weapons during the Second World War through socio-economic political context in current history. In this regard, Gilbert Ziebura’s research on pre-Second-World-War economy and politics including that of Japan is worth a close look (World Economy and World Politics, 1924-1931, First Published in German in 1984, Translated into English by Bruce Little and published by Berg Publishers Ltd., Oxford: UK, 1990).

Ziebura mainly analyzes in this research the post-war world economic structure such as the Versailles System (1924-1929) and the Washington System (1922-30) which tried to reconstruct the world economy after the First World War yet failed in doing so (pp.77-122) and lead the economic causes of the Second World War mainly through the Great Depression of the year 1929 (pp. 139-166). He analyzes Japan’s economic and foreign policies (pp.123-131) and her militarism (pp. 158-162) in this aspect. Japan, with the help of the USA, began to enter into a modern industrial society through Meiji reformation in 1867, and cooperated with the USA in expanding her economic and political power in South-Eastern Asia. Although her productivity swiftly grew far exceeding that of Europe and the USA, the depression and global economic crisis of 1920-21 shrank her foreign market, and the price of Japanese industrial and agricultural products rapidly fell down. Japanese population was quickly growing, and their economic and social tensions became worsened due to the crisis of world economy. “If Japan was to resolve her demographic, social and economic problems, only two courses presented themselves: either enhance foreign trade, especially with the United States and China, and thereby implicate Japan more deeply in the international division of labour, or if this approach did not succeed, expand by force of arms into the Chinese hinterland in order to gain the material basis of policy of economic autarky” (p.128).

Beneath the surface of a seemingly peaceful trial to keep following the world economy system, “a fundamental shift in Japanese policy was under way… Japan’s orientation shifted abruptly and became increasingly radicalized throughout 1931” (pp.158-159) mainly because the Great Depression most strongly hit Japanese economy whose row-materials were severely depended on imports (90 per cent: p.158). ‘Three mutually reinforcing factors’ accelerated this procedure: “1) the political victory of the military over the ‘liberal’ alliance; 2) the mounting confrontation with China over Manchuria; 3) the steep decline in economic relations with the rest of the world as the result of the Great Depression” (p.159). Japan finally invaded Manchuria and occupied the territory in 1931. Japanese domestic tensions were eased, and the military kept holding its power over politics based on the agreement of Japanese industries on “the principle of territorial expansion” (p.163). The accumulated burden of the world economic system after the First World War critically hit the Japanese economy which was swiftly jumping into the imperialistic world-economy system despite her maybe-too-late start, and Japan chose to resolve her problems using her military force, the worst type of accumulated human violence.

How can we, then, understand the Japanese individuals’ surrender and submission to this collective violence executed by their military and imperialistic government? Peter Berger offers a useful tool to answer this question in his Sacred Canopy (Doubleday: New York, 1967: the writer of this work used the Anchor Books edition printed in 1990). Here, analyzing religious phenomena, Berger writes that all social phenomena are through the procedure of externalization from individuals, objectivation in society, and internalization into individuals. Human society controls individuals through legitimation procedure, and more legitimation follows after forgetting or resistance of individuals, systematizing and structuring social engineering procedure (pp. 3-51).

In this procedure, individuals tend to surrender to society. Berger explains this malignant aspect of human psyche based on Sartre and Nietzsche. “Every society entails a certain denial of the individual self and its needs, anxieties, and problems,” and society facilitates “this denial in individual consciousness.” This “self-denying surrender to society” is the attitude of masochism, “the attitude in which the individual reduces himself to an inert and thinglike object vis-à-vis his fellowmen, singly or in collectivities or in nomoi established by them” (p.55). This leads the individual to helpless submission to society and self-annihilation, strengthening “the formulas of masochistic liberation.”: “‘I am nothing—and therefore nothing can hurt me,’… ‘I have died—and therefore I shall not die,’…and then: ‘Come, sweet pain; come, sweet death’” (p.56).

While the Japanese military and government were eagerly trying to escape through violent warfare from Japan’s multiple burdens derived from the post-war time world-economic situation which was being worsened, Japanese individuals were surrendering and submitting to their institutionalized power structure following steps of the formulas of masochistic liberation. The Japanese pseudo religion Shinto, deifying and worshipping Japanese emperors almost forcing to sacrifice individual lives for the sake of their nation, must have accelerated this crazy procedure toward the point at which the Japanese executed massive live-human experiments and slaughtering.

Where was God while all these were happening? ......

III. THEOLIGICAL ANALYSIS:

EVIL—God’s Fault or Human Responsibility?

When humanity accounts seemingly unjust situations, the question of theodicy is raised: is God fair and almighty?! The question whether God is fair derives from the traditional doctrine of retribution: God offers hardship as punishment when humanity as a whole or as an individual ‘misses the mark.’ The question whether God is almighty inevitably follows when God does not seem fair: why do bad things happen to good people? Why does God give one such terrible hardship when one did not do anything bad? Is God really just and almighty? Where does this evil power come from that overwhelms humanity from time to time? Is God really the very creator of everything in the world, even including anti-God, Evil? ...

The problem of theodicy, therefore, essentially requires humanity to understand God’s creation procedure. Two representative theologians, Paul Tillich and Robert Cummings Neville, interpreting Christian doctrine of Creation ex Nihilo, offer two different viewpoints on God’s Creation and the problem of theodicy.

First, Tillich follows Neo-Platonic and Augustinian interpretation in his Creation theology (Systematic Theology, vol.1, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago: Illinois, 1951: the writer used the paperback edition published in 1973, pp. 235-270). He declares that God as being-itself is the abysmal ground of being, meaning, and ontological structure of being. Yet, “there is an absolute break, an infinite jump between the finite and the infinite,” although “every finite participates in being-itself and its infinity.” “This double relation of all being to being-itself gives being-itself a double characteristic”—transcendence from ‘abysmal’ and presence from ‘creative’ (p.237). Therefore, since there is the absolute infinite jump between the finite (the world of all beings) and the infinite (the ground of being), the latter creates the former with the risk of limitedness—flaws. In God’s creation procedure, humanity becomes alienated from God and falls into its existential anxiety. This is the foundation of the problem of theodicy.

From human part, this procedure is the very procedure of humanity’s choosing the finite human freedom. Humanity chooses its own limited freedom entirely negating the essence, the very ground of its existence—God. This is the starting point of ‘the doctrine of falling.’ The matter of theodicy stands in the gab between these two—God’s creation and human falling: human finitude and their limited freedom, the foundations of human creativity, cause human providence both collectively and individually. Although God only creates life, not death, and good, not evil, since God risks ‘the finite’ and ‘the imperfect’ for the sake of creation, and since humanity absolutely negates its ground of being and absolutely alienates its existence from its essence, the problem of theodicy, the flaw of the finite world, is inevitably inherited in God’s Creation.

In this paradoxical reality of human existence, God actualizes God’s telos, and humanity experiences alienation and providence. Although there is no evil or any similar evil power that can control humans from outside humanity, the problem of providence and suffering still must be in human reality. According to Tillich, human ways of answering to the question of theodicy in the suffering of existence are faith in providence and truthful prayer. This the only way humans can, if partly, participate in God’s creation procedure: through their faithful true prayer, humans can make changes in God’s future creation.

Neville interprets Christian Doctrine of Creation ex Nihilo differently than Tillich does in his God the Creator—on the Transcendence and Presence of God (SUNY, Albany: New York, 1992; First published by The University of Chicago Press in 1968). Through comparing ‘conceptual distinction’ with ‘real distinction’ (pp. 307-312) and ‘cosmogonical constitutive dialectics’ with ‘cosmological methodological dialectics’ (pp. 125-167), Neville argues that human understanding of God and creation must be conceptual, so metaphysical, not empirical, although human desire to understand God’s creation derives from human religious experience. This is true because humans can entirely understand God’s creation only through their metaphysical epistemological exercise. Individuals living in the finite world cannot completely recognize God’s infinite creation procedure as a whole in their daily lives, if they may have the glimpse of it from time to time. For Neville, therefore, theologies of God and creation are theoretical metaphysical hypotheses, not empirical statements or declarations.

Starting from his criticism of cosmological methodological dialectic that it cannot offer a tool through which humans can completely understand the constitutive procedure of creation, through his construction of constitutive cosmogonical dialectic that explains both “the dialectical structure of reality and the dialectical structure of our philosophy that exhibits reality’s structure” (p.148), Neville reaches to his interpretation of the Creation ex Nihilo as the following (pp.94-119):

God creates the finite world ex Nihilo. ‘Nothing’ here does not mean ‘not a substance’, but means some sort of ‘beyond human recognition.’ Creatures in the finite world have essential features and conditional features, yet God’s essential features are not definable through human epistemology. Therefore, God’s creativity is the essential feature of God’s creation/creating, not of God’s self/being. Also, God the Creator is conditioned by God’s creation. In other words, the being-itself, God, is self-creating and self-conditioned. This means that without God’s creation and God’s created there is no God. Still, God the creator is independent from the created as a whole in the creation because the created as a whole is entirely dependent on the creator, and the creator creates out of nothing. In this way, God is present in the finite world being dialectically merged with the created in the creation, simultaneously transcending the finite world. Yet, this is only conceptual and hypothetical, not real. In other words, this is the epistemological way through which humans can understand the relationship between God and humanity.

Conditionally God has three features—the creator, the creation, and the created, the first being the essence of the other two, and these three features of God dialectically fuse one another in the finite world without composing any linear relationship as methodological dialectic does. Essentially God has no feature—again, this does not simply mean the God has no-’thing’ as God’s feature. Rather, this means that God’s essential features are not explainable through human metaphysics. Through this spiral logic, Neville fills up ‘the absolute break’, ‘the infinite jump’, between the infinite and the finite that is present in Tillich’s interpretation of Creation ex Nihilo. Since God’s essential features, if not traceable, cannot be separated from God’s conditional features, God, being-itself, is present in the finite world with God’s conditional features, and is essentially transcendent beyond the finite world simultaneously. There is no gap between God’s presence and transcendence.

Also, in Neville, there is no ‘absolute falling’ of humanity from God, either. Humans are present in God’s creating act as the created, entirely depending on the creator yet conditioning the creator at the same time. Humans are, therefore, co-creators in God’s creation. Then, how does Neville treat the problem of theodicy in the finite world?

Neville clearly argues that the problem of theodicy derives from treating God as a person. When humans suppose that God has a ‘loving and forgiving character’ like humans, they come to raise the question of theodicy. However, “there is no need to apply human moral criteria to a supposed antecedent divine plan, which trips on theodicy” (Symbols of Jesus—A Christology of Symbolic Engagement, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: UK, 2001, p. 42). This does not mean that the finite world is only good without any suffering. Rather, this means that humans had better not ask questions about God’s almighty power and divine goodness based on human moral criteria because God is not a person.

Unlike Tillich’s, Neville’s interpretation of Creation ex Nihilo is free from the problem of theodicy. This is so because God in Neville is not just the creator, but also the creation and the created including humanity. His God is source, act, and product of creation, not a simple agent of act (creation) as in Tillich--although Tillich defines God as the ground of being, God certainly takes a role as a subject of act (creation) in his interpretation of creation ex Nihilo. Yet he dose not clearly explain how the infinite ground of being leaps ‘the infinite jump’ between the infinite and the finite in actualizing its creation of the finite. Therefore, Tillich unavoidably concludes that “the creation of finite freedom is the risk which the divine creativity accepts,” therefore admits the problem of theodicy, although the question of theodicy is not about the existence of evil (Ibid, p.269). On the contrary, since Neville’s God is the creator, the creation, and the created including humanity, and since God simply creates, not actualizing God’s telos as Tillich says, God does not have to be judged based either on human ethical or legal criteria or on the matter of almighty. God is absolutely free from any type of human judgment in Neville.

If so, what is evil for Neville? He uses this term ‘evil,’ with a small ‘e,’ as the meaning of malicious human doing or human suffering. For example, he uses the term ‘evil’ in Symbols of Jesus as the following:

Personified notions of God coupled with people’s sense of self and sense for the righteousness of their desires have done much evil (p. 54).

The depth of evil [the ravages of war and the suffering of innocents] and the blind brutality have caused many not to rest… (p.195)

…acknowledging not only…but also the social and intellectual evils that have been done in the name of these very Christological symbols (p.261).

This work is now almost at conclusion. To admit that theologies are metaphysical epistemological hypotheses is to admit that a theology (hypothesis) with least logical flaw is the strongest, so the most persuasive. In this respect, Neville’s interpretation of Creation ex Nihilo has its strength in that it has almost no logical defect in explaining God’s transcendence and presence and the relationship between the infinite God and the finite world. In this fine theology, humans are co-creators of the finite world, and there is no problem of theodicy. There is no evil separate from God or humans, either. Regardless good or bad, everything in the world is from God and also from humanity. Evil in here certainly is humans’ malicious acts and suffering accumulated throughout history. This matches the conclusion of the above socio-historical analysis of Unit 731 case: Unit 731 case is the result of accumulated burdens of imperialistic world economy and collective masochistic surrender of individuals to objectified institutional power of society—evil.

To agree with Neville requires courage. It is so because it means to admit humanity as the source of evil power. If this is to be so, humanity as a whole can never be free from the very responsibility for such evil done throughout the whole history. When humans can believe any personified God who creates alone and who loves and forgives, it is easier to escape from such severe responsibility and feel safe in God’s protection and forgiveness. Nevertheless, it is true that a theology must be a theoretical hypothesis derived from human metaphysical exercise. Therefore, a theology with the least logical flaw in explaining God and humanity should be taken as the theology that explains our finite world. And through Neville’s theology, one of the finest hypotheses in this respect, we get the conclusion that humans are the subject of evil doing, evil power. This makes the writer tremble…

… The writer finally tries to stand up with or without courage, and thinks: what to do, and how… Alvin Toffler says in his Powershift that knowledge, wealth, and violence are the foundations of power structure in our global society. These foundations are so systematically organized and institutionalized as a never-defeatable monstrous fortress that there seems not a tiny single hole to sneak through….

…So, the, writer, prays…

Bibliography

Paul Tillich, Systematic Theology, vol.1,The university of Chicago Press, Chicago: IL, 1973

Robert C. Neville, God the Creator, SUNY, Albany: NY, 1992

______________, Symbols of Jesus, Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge: UK, 2001

Peter Berger, The Sacred Canopy, Anchor Books, Garden City: NY, 1990

C. Wright Mills, The Sociological imagination, Oxford Univ. Press, New York: NY, 1959

P. Williams & D. Wallace, Unit 731—the Japanese Army’s Secrets of Secrets ,Hodder and Stoughton, London: UK, 1989

Hal Gold, Unit 731 Testimony, Yenbooks, Singapore: Singapore, 1996

The Other Holocaust: Nanjing Massacre, Unit 731, Unit 100, Unit 516, http://www.skycitygallery.com/japan/japan.html

News Watch, http://www.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/NanjingMassacre/Watch.html