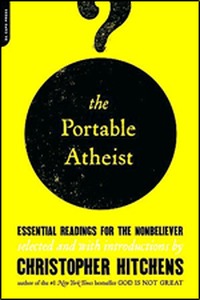

Christopher Hitchens, ed., The Portable Atheist

(from

here).

Index of Original Excerpts | Responses | Key to Authors

|

|

|

Christopher Hitchens, ed., The Portable Atheist |

This is a collection of colorful and thoughtful responses to literary excerpts bearing on atheism. Unless otherwise mentioned, excerpts are compiled in Christopher Hitchens, ed., The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Nonbeliever (Da Capo Press, 2007), and page numbers refer to that book.

Ayaan Hirsi Ali, How (and Why) I became an Infidel

Elizabeth Anderson, "If God is Dead, is Everything Permitted?"

Alfred Jules Ayer, "That Undiscovered Country"

John Betjeman, "In Westminster Abbey"

Chapman Cohen, "Monism and Religion"

Joseph Conrad, "Author's Note" from The Shadow Line

Richard Dawkins, "Atheists for Jesus"

Richard Dawkins, "Why There Almost Certainly is no God"

Daniel C. Dennett, "A Working Definition of Religion" from "Breaking Which Spell?"

Daniel C. Dennett, "Thank Goodness!"

Albert Einstein, "Selected Writings on Religion"

George Eliot, Evangelical Teaching

Anatole France, The Garden of Epicurus

Sigmund Freud, The Future of an Illusion

Martin Gardner, The Wandering Jew and the Second Coming

Emma Goldman, The Philosophy of Atheism

A. C. Grayling, Can an Atheist Be a Fundamentalist?

Sam Harris, "In the Shadow of God"

Thomas Hobbes, "Of Religion" from Leviathan

David Hume, excerpts from The Natural History of Religion and Of Miracles

Penn Jilette, "There is No God"

H. P. Lovecraft, “A Letter on Religion”

Karl Marx, Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right

Ian McEwan, "End of the World Blues"

H. L. Menken, "Memorial Service"

John Stuart Mill, "Moral Influences in Early Youth: My Father’s Character and Opinions"

George Orwell, excerpt from A Clergyman's Daughter

Bertrand Russell, “An Outline of Intellectual Rubbish”

Salman Rushdie, "Imagine There's No Heaven: A Letter to the Six Billionth World Citizen"

Carl Sagan, The Demon-Haunted World

Carl Sagan, The God Hypothesis

Percy Bysse Shelley, "A Refutation of Deism"

Michael Shermer, "Genesis Revisited: A Scientific Creation Story"

Benedict de Spinoza, Excerpt from Theological-Political Treatise

Victor Stenger, "Cosmic Evidence," from God: The Failed Hypothesis

Victor Stenger, Why Is There Something Rather Than Nothing?

Leslie Stephens, An Agnostic's Apology

Charles Templeton, "A Personal Word" from A Farewell to GodCharles Templeton, "Questions to Ask Yourself" from A Farewell to God

Mark Twain, "Thoughts of God" from Fables of Man

Carl Van Doren, "Why I am an Unbeliever"

Steven Weinberg, "What about God?"

|

|

|

Ayaan Hirsi Ali |

Ali suffered from Islam culture by sexual abuse and suppression as a woman and a slave of God (Allah). She escaped and ended up in Holland. In Holland, she decided not to follow Allah and her clan after watching the Twin Towers topple in the name of Allah, when she was studying political science to understand her background. In turn, she became an atheist. As an atheist, she felt freedom and emancipation because religion could not stifle her anymore.

Her story is similar to that of a fundamentalist Christian becoming an atheist because of the absurd and awkward dogma. That a person escapes from the dogma means the individual makes a new relationship between the individual and self as well as the individual and others. This process plays a pivotal role in finding one self by doubting and wrestling with the dogma. Consequently, they will find their uniqueness and differences. Those characteristics help people to understand who they are as independent human beings. Indeed, this way is one that Christianity emphasizes. This is because “God loves differences” . For example, God created Adam and Eve, but this unity created diversity such as Cain and Abel, Noah and the Flood, Babel and its tower.

Likewise, human beings are created to be themselves. And perhaps God allows people to do what they want to be happy in the world, so that God provides time and life without costs. Therefore, if people know exactly who they are, the world might be in peace.

However, if morality stems from a survival mechanism of human beings, since human beings chose to make society to protect them and be competitive to survive, is it not problematic to threaten the minority or to consider the majority as always superior to the minority?

Ali outlines the (primarily male) power and dictatorship that ruled her life during her time as a Muslim woman in Somalia. She recounts coming to terms with the fact that she could not force herself to pretend in believing something that no longer held any rational weight. She explains how the most difficult part of leaving her faith was the fear of burning in Hell, for she had vivid descriptions that had been passed down to her from a number of sermons, and those descriptions inflicted a deep-seated fear that trapped her for a long time in a faith she no longer wanted a part in (412). She notes addressing the problem of evil as a child, and she admits how romance novels gave her hope for a better future in her teenage years. It was in the moments of the 9/11 tragedy that Ali felt she needed to definitively decide where her loyalties rested, and after reading The Atheist Manifesto, she was able to speak aloud what she had known to be true for some time: she was an atheist (413). After this clarity, she speaks of her psychological journey to understanding how she must become her own moral compass and be responsible for making her own life meaningful here and now on earth.

Ali's account of religion puts an impetus on religious communities to examine the ways in which they cause harm alongside and sometimes in spite of the good and the meaning that people find within them. Religious traditions are complex, and it would be dishonest to ignore the atrocities that have been done in the name of religion's deities and sacred texts in favor of focusing only on the ways in which these traditions build communities, advocate love and justice to the world, seek Truth, and give purpose to humanity. To remain situated in a religious tradition is to take up the responsibility of knowing how that tradition manifests in the world, for better or for worse. If we take this responsibility seriously, then within our communities we will ask questions, engage in interpreting sacred texts for present-day realities and ethics, consider what practices and beliefs need adaptations, and remain vigilant to how religious traditions contribute to destruction so that it might be stopped. The biblical notion of binding and loosing scripture could be applied here as symbolic of us interpreting where our traditions, beliefs, and practices fit in our present-day world, and how we live them out faithfully.

Ayaan Hirsi Ali narrates her life journey from young Muslim girl in Somalia to atheist in Holland. Growing up a Muslim girl in Somalia meant she had to submit to Allah and to the male members of her family. Ali felt torn between her desire to be dutiful to her clan and God and her desire for justice and life. Submission for Ali meant slavery, which was enforced by the threat of hell. Ali's desire to submit finally broke when her father attempted to marry her to a stranger. She escaped from her clan to Holland, but still struggled with her Muslim heritage. She slowly acclimated to life in Holland, exchanging her hijab for jeans while reading the philosophers of the European Enlightenment. Ali still considered herself a Muslim, living in a state of cognitive dissonance as the changes in her circumstances slowly seeped into her religious life. The terrorist attack on 9-11 felt like a definitive moment for Ali to confront her growing cognitive dissonance and her growing doubt. Her doubt meant she no longer submitted. Ali realized that by asking the question whether or not she was a Muslim she was already an atheist and infidel. Empowered by her admission of atheism, she began to search for meaning in life free of cognitive dissonance. Previously life meant submission. Now life means freedom. Ali is free to be and free to die, no more and no less.

I wonder how much cognitive dissonance Ali has banished from her life? Ali felt strongly pulled in two irreconcilable directions. She could follow the strict dictates of her Muslim upbringing with its list of rules and punishments or she could follow her own desires, free to choose as she is wont. Atheism, since it has no creed, places no strictures on her desires. Will her conflicting desires not lead to some reassertion of cognitive dissonance? Of course, she is free to work out these conflicts on her own terms. Perhaps this freedom, the freedom to doubt and question, to challenge that which seems dissonant, is what Ali seeks.

In leaving the religion of Islam, Ayaan Hirsis Ali felt especially that she was “leaving Allah” (477). But she did not feel that change right away in the process. It was preceded by various doubt-causing conflicts. She resisted their implications as much as she could until her faith crumbled, little by little, and then finally gave way. The doubt-filled though innocent questions she had as a child returned with a vengeance. Her questions mainly concerned Allah's allowance of social injustice, including the particular forms she experienced daily but had learned to ignore through moral technologies of “shame and obedience” and fear of “betraying” her family and community. As she grew older, she struggled to contain a growing sense that her conformity to the cultural meaning of a good Muslim young woman did not express who she most truly was. Then there were the horrifying teachings of hell which, try as she might, she could not comprehend without living in perpetual fear. Last but not least, she was challenged by acknowledging her inabilities to repress her natural sexual imagination and desire (as a good Muslim young woman would do), and depressed by the dreadful prospect of a permanent marriage arranged by people who do not care what she truly wants, but only what is thought to be good for her. In all this, she was at odds with the Islamic identity she had been socialized into, but was far from breaking off her relationship with Allah. More directly than anything, reading books at university caused her to raise critical questions about her faith and eventually realize that the god she believed in was no god at all, and that the whole of Islam had been holding her back and keeping her spirits down. It seems that Ali's process of de-conversion was not very self-directed until her university years. For her, it was forced, little by little, but not forced from without (as was Islam) but rather from within. At the point when she most explicitly denounced her god, she explains, “I realized that I had left Allah behind years ago,” then looking in the mirror and putting words to that realization: “I don't believe in God” (p. 479).

I am inspired by the radical change in personal identity that Ali was able to make in spite of how dangerous, isolating, and painful the means of change were. She seems to have been so alone, save for the kindred spirits she found in the philosophers whose books she read. Her story shows how de-conversion can be the hardest undertaking a person chooses, or, what is perhaps more accurate in her case, the hardest experience a person cannot help but undergo. For some people it takes various different causes of resentment coming together repeatedly, accumulating and compounding, until it all reaches a saturation point and is then suddenly release, bringing “relief…and real clarity” (479). Although Ali does not seem to express it about her own case, for other de-converts the aftermath also involves regret, embarrassment, confusion, and other negative feelings which can be difficult to work through. The pattern is not unlike what occurs in cycles of abuse and the termination of abusive relationships.

For Ayaan Hirsi Ali, the development through and past religious faith “was a long and painful process” (477). In this short essay, Hirsi Ali describes her early religious identity as an obedient, Allah- (and hell-) fearing young woman, struggling to conform, yet peppered with the shame of wanting to ask questions. It wasn't until she was exposed to Western culture and Enlightenment ideas that she began moving away from her faith in earnest. She finally “admitted” to herself that she was an atheist after the September 11 terrorist attacks on the Twin Towers and embarked on the quest of finding meaning and purpose and ethics without Allah or religion. She concludes that “the only position that leaves [her] with no cognitive dissonance is atheism” (480); but beyond a mere lack of dissonance, Hirsi Ali speaks of atheism as a philosophy that frees her to live authentically, responsibly, and morally– to be a “better and more generous person” without compromising her intellectual integrity or her personal will and vigor for life (479). She experiences atheism as a path toward living life more “intensely” – it “replac[es] both the siren-song of Paradise and the dread of Hell” (480).

Compared to some of Hirsi Ali's more politically and socially polemical pieces, this one was strikingly personal – focused not on anti-Islamic or anti-religion arguments, but rather limited to a genuine and highly relatable story of philosophical and ideological growth and development. From her youth, Hirsi Ali was driven and compelled by a desire for truth, wisdom, and moral integrity, which she eventually found in atheism. The story of a university student's movement away from the religion of her youth seems to be a common one – and one that I share myself. However, it is interesting to note the difference between the level of rebellion and courage required to detach oneself from the psychological, social, and spiritual bonds of a conservative or fundamentalist tradition as opposed to a more progressive or moderate tradition. For example, gradually moving away from some of the more traditional theism of my gentle, progressive Lutheran upbringing was a relatively smooth, minimally distressing process, during which I was able to maintain a connection with and fondness for my original community. But Hirsi Ali's passage from faith to atheism required a more stark denial and full rejection of her old community. For her, there seemed to be very little middle ground: after the September 11th terrorist attacks, she observed that “Osama bin Laden's justification of the attacks was more consistent with the content of the Koran and the Sunna than the chorus of Muslim officials and Western wishful thinkers who denied every link between the bloodshed and Islam.” Thus, she felt that she was forced to choose a side: if she did not support bin Laden, was she a Muslim at all? In addition to her personal beliefs, Hirsi Ali has also been an outspoken commentator on Islam as a social and political force. As Hitchens points out in his introductory comments about Hirsi Ali, she quickly turned from the “false hope that Islam could be open to a reformation” toward a belief that Islam must be defeated. However, Hirsi Ali's most recent book, published in 2015, appears to call not for the annihilation of Islam, but for its reformation; I would be very curious to read a sequel to this short autobiographical essay that might give an account of her seemingly evolving views on Islamic society.

Ali’s essay is a very courageous and vulnerable personal narrative of her transition from Islam to atheism. From her earliest memories she resented having to submit to her brother, but that resentment was tinged with guilt for questioning Allah. As she grew older, she was disturbed that family honor codes “seemed principally to reside in the control, sale, and transfer of girls’ virginity” (478) but still she kept her silence. It was only when her father arranged for her to marry a stranger that she finally rebelled by immigrating to Holland. There she studied political science, trying to understand “why Muslim societies – Allah’s societies – were poor and violent, while the countries of the despised infidels were wealthy and peaceful” (ibid.). After September 11th, Ali’s growing religious crisis finally came to a head. She picked up a book about atheism and “Before I’d read four pages, I realized that I had left Allah behind years ago. I was an atheist” (479). This dramatic change led to an exhilarating process of deciding for herself what morality she would embrace. Ultimately, choosing to be a good person seemed significantly more moral than being good because one feared hell. For Ayaan Hirsi Ali, abandoning the fear of hell and the hope of heaven only increased the intensity and beauty of her life on Earth.

Growing up in Evangelical Christian circles, I was often told that nothing convinced people to believe more than a good personal testimony. Apparently, that principle holds for disbelief as well. How can one argue against such a vulnerable and perfectly sincere confession? You cannot fake years of painful religious guilt, and nothing can replace the genuine evangelist’s essential conviction: I believe so strongly in the validity of my experience that I will honor it by sharing even the uncomfortable details. Did Ali need to mention that sexual cravings led her to finally abandon her family and country? Of course not. Will that confession be used against her by those who want to condemn her and tarnish her name? Of course. It is precisely in the lack of such calculations that one senses the properly motivated testimony. All her words ring true, including those concerning her commitment to realizing religious ideals of moral excellence and generosity “without suppressing my will and forcing it to obey an intricate and inhumanly detailed web of rules” (479). I resonated with her struggle throughout, but nothing moved me more than her closing words, which I will echo as part of my own creed: “Death is certain, replacing both the siren-song of Paradise and the dread of Hell. Life on this earth, with all its mystery and beauty and pain, is then to be lived far more intensely: we stumble and get up, we are sad, confident, insecure, feel loneliness and joy and love. There is nothing more; but I want nothing more” (480).

This article is the touching story of Ayaan Hirsi Ali, her journey from a believer to an atheist. In the article the author makes the argument that belief systems use fear tactics to exercise control over human beings. The author argues that once she came out of the clutches of believing in a God she was able to think freely and stand on her own reason with self respect. She did not have to accept contradictions any more or hide any thing. The author argues that morality comes not from the pages of a sacred book but from oneself because of one's need to function within a society. In short, the author through her personal story argues like any other atheist: life in this world is what is real only that life matters, not any superstitious beliefs about that life.

This article was very real to me because the arguments were backed with real-life experiences. In many ways I could relate to the writer considering the fundamentalist Christian upbringing that I had as a child. The Christian religion was seen only in the perspective of heaven and hell and being a Christian in my life was all about somehow escaping hell and securing heaven. So the story of the author resonates with me in a very big way. I agree with the author on the point that religion often does not give a person the freedom to think the way he or she wants to think. But I believe that any religion can be seen in many perspectives. I believe that if Christianity is seen only in the perspective of escaping hell, then it has failed in its purpose. But if the same religion is seen in the perspective of love it gives me a ray of hope (even if it is a belief) for counteracting the confusions and contradictions of this world.

As a child she was shameful and obedient. As a teenager she was afraid and as an adult she was free. In How (and Why) I Became an Infidel, Hirsi Ali traces her escape from the cognitive dissonance of the Muslim faith of her youth to her adult atheism. Having been exposed to Western philosophies in college, Hirsi Ali began to find secular life fulfilling and not damning. The 9/11 attacks are posed as the pivotal moment when Hirsi Ali was forced to choose sides. Through her choice, Hirsi Ali discovered a life with more meaning and intensity. Seeing herself in others allowed her to accept her own atheism and to realize the potential of a truly mortal life.

The sincerity of Hirsi Ali’s youthful experiences and her conversion to atheism are unquestionably sincere. Her testimony, however, is hardly compelling. It reads as a story written time and time again. Employing rhetorical vocabulary throughout, Hirsi Ali describes having Islam “drilled” into her during her youth and preachers “hammering” ideologies into her head. I do not mean to diminish the validity of her life experience, but to suggest that the inclusion of this piece (particularly as the final chapter of Hitchens’ collection) lacks a certain depth of dialogue. Religion restricts, atheism frees. No doubt this is true for many non-believers, but the level of discussion must be pushed and expanded, not simplified.

In “How (and Why) I Became an Infidel,” Ayaan Hirsi Ali outlines the steps in her rejection of the anthropomorphized view of Allah that her Somalian fundamentalist upbringing foisted upon her to her realization that no god is required for her to author the meaning of her own life. The first step in her journey is the inability to resolve the problem of theodicy and the threat of a loveless arranged marriage sends her packing to The Netherlands. There the clash between her inherited Islamic worldview and her university education plus the encounter with personal freedom leads her to bargain with Allah—surely he values education and the sins she is committing are small. The events of September 11, 2001 push her away from Islam and what she sees as its inherent violence while reading Philipse’s The Atheist Manifesto leads her to realize that Allah is a human invention designed by the powerful to control the weak. By “firing” her god, her parents, and her culture, Ali takes up the challenge to think for herself, develop an internal moral compass, and take on responsibility for her decisions (477, 478, 479). When asked why she does not convert to a more humane religion, such as Christianity, she responds that any religion that attempts to control behavior or paper over the certainty of death is one that does not accept life as it really is with its “mystery and beauty and pain” alongside its sadness, insecurities, and loneliness (480).

Ali’s essay raises the question of whether her flight to atheism is a well-thought-through decision or an example of the all-or-nothing thinking that characterizes fundamentalism. Is the drastic swing of the pendulum a step in her recovery that will ultimately lead to a middle ground between fundamentalism and atheism or her final landing spot? Studies of former Christian fundamentalists reveal that few if any ever return to the fundamentalist fold, but those who seek mental health care experience anger, hurt, guilt, and loneliness along with anxiety and depression about the meaning of life and lingering fears of punishment (see Darren E. Sherkat and John Wilson, “Preferences, Constraints, and Choices in Religious Markets: An Examination of Religious Switching and Apostasy,” Social Forces 73 (1995): 1014-1016; James C. Moyers, “Religious Issues in the Psychotherapy of Former Fundamentalists,” Psychotherapy 27 (1990): 42-43; Gary W. Hartz and Henry C. Everett, “Fundamentalist Religion and Its Effect on Mental Health,” Journal of Religion and Health 28 (1989): 209-210, 214-215). While Ali’s essay points to her resolution of the anger over sexism, the hurt of parental betrayal, the guilt over sin, and the fear of hellfire, her comment that Christianity’s “heavenly gardens” aggravate her hayfever may indicate a cynicism that suggests her journey is far from finished (480).

As a Somali female, Ayann did not feel comfortable to the Muslim tradition even before before her teenager, during the time she was growing, she tried hard to conform herself into the Koran code since she was in fear of hell what every preacher hammered into her mind. She escaped to Holland, ended up study in college, gradually she realized Allah or Hellfire did not punish her even she was not following the requirement, then the 9/11 made her to proclaim she had no God anymore. She was asked if she would like to adopt Jesus Christ, but for her he is just angel in her mother’s story. She chose Atheism which she read a book about, she believed she could get the relief as it has no cognitive dissonance to her, neither Paradise or Hell, death is forever, she wants nothing more than current reality.

It could be a sad or angry story for Christian or Muslim, but it tells the reality of secular world, when people has no fear or hope, they live on their conscience which they only believe in. The balance of the life depends on how the conscience reliable to be right and strong. People becomes rely on themselves more than any others. That does not mean they are better or worse, I believe it is just the way people choose to have their connection with the Ultimate, which is there no matter people accept or reject. Like every kid has a father, no matter they accept his father or not. In Atheist world, the Ultimacy is themselves, they become God for themselves, but they forget their conscience comes from the Ultimate still, no matter how they recognize their Ultimate.

Somali-born ex-Muslim Ayaan Ali presents a moving account of her slow break with an oppressive religious culture and her eventual conversion to atheism. Ali’s youth took place in a culture where Islamic faith was at the very center of life, culture, and identity. She writes, “All my life I had wanted to be a good daughter of my clan, and that meant above all that I should be a good Muslim woman, who had learned to submit to God – which in practice meant the rule of my brother, my father, and later my husband.” This particular form of Islamic culture was extraordinary repressive of women (their bodies, their desires, their autonomy), and the most important cultural value centered around the “control, sale, and transfer of girls’ virginity.” In order to escape an arranged marriage Ali found herself in Holland and attending a University. Gradually her worldview and faith dissolved, eventually inspiring her to become an atheist upon reading Herman Philipse’s The Atheist Manifesto. “Before I’d read four pages, I realized that I had left Allah behind years ago. I was an atheist. An apostate. An infidel. I looked in a mirror and said out loud, in Somali, ‘I don’t believe in God.’ I felt relief. There was no pain but a real clarity.”

This piece is an important reminder of just how liberating atheism can feel, especially for those who come from oppressive religious backgrounds (even one’s far more moderate than that experienced by Ali). I often find myself distancing myself from atheism ( I came to my religious naturalism not from a commitment to naturalism per se, but as a committed radical monotheist), due in part to its dismissal of the value of religious traditions, but seeing this woman’s journey away from an oppressive upbringing and towards an affirmation of her individuality and rationality as a woman was heart warming. The means for this transformation were simple: pluralism (her exposure to another culture), and education. As one piece of her worldview fell after another, unable to handle the internal contradictions and cognitive dissonance that her evolving worldview presented. Atheism became the only logical choice for her. Her last words are worth quoting at some length, as they are quite beautiful.

The only position that leaves me with no cognitive dissonance is atheism. It is not a creed. Death is certain, replacing both the siren-song of Paradise and the dread of Hell. Life on this earth, with all its mystery and beauty and pain, is then to be lived far more intensely: we stumble and get up, we are sad, confident, insecure, feel loneliness and joy and love. There is nothing more; but I want nothing more.

Hirsi Ali opens her essay with a the idea that becoming an atheist was not a quick and fun decision but a long and painful process. She ends her story with a simple and concise summation of her journey: an attempt to get away from cognitive dissonance. Hirsi Ali’s story starts with loyalty to her clan above all. Her relationship to religion is through her clan. She speaks of Hell as being a motivator for her to keep in line in addition to how her clan would react to her thoughts. The relationship that she has with the men in her family, along with the limitations placed on her simpy for being a woman, made her start to question. Eventually she was able to escape Somalia and make it to the Netherlands where she was able to reflect freely. In her search for a system that made sense, atheism provided the least cognitive dissonance. She writes that being able to admit to herself that she was an atheist brought her relief.

Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s text was incredibly moving. She writes of the oppression that religion had on her when she was young and how it pushed her towards seeking a better life. Starting the work with a notion of pain and suffering during the journey ensures that her words are not heard as attacking but rather as lamenting. Her story brings to mind some interesting questions. At what point is religion being used to defend a cultural way of life? And at what point is religion simply the scapegoat? Hirsi Ali had a horrible experience with religion that eventually led her to become an atheist. However, at what point is her focus on Islam truly Islam and at what point is it the culture in which Islam found itself? Or, are Islam and the culture separable and Islam is truly to blame for her oppression? These are just some of the questions that the text leaves me with.

Ayaan Hirsi Ali relays her painful journey from Islam to Atheism in the essay “How (and Why) I Became an Infidel” (477-80). She grew up in Somalia and from an early age learned the hard lesson of submission to the will of Allah. As a little girl though she could help but wonder why her opinion was inherently less valid then her brothers. The clan emphasis on obedience and the warnings of hell pushed her to try and be a faithful Muslim, wear the black hijab, pray five times a day and other commands of the Koran and Hidith, but, she relays, it was “books and boys” that saved her in the end. Reading trashy Western romance novels demonstrated for her that an alternative world existed where girls could exercise personal choice. So, when her dad arranged her marriage to a stranger, she ran away to Holland. It was at University, while reading Enlightenment philosophers, that she first realized she was an unbeliever. The relief was immediate and palpable. No more future hell-fire and, more importantly, her moral compass was located within herself, not an ancient book. As a new Atheist she frequented Museums in order to see really old dead people. Faced with bones thousands of years old, she realized that if it had taken Allah this long to raise the dead, then the chances of retribution for her enjoying her life were slim.

Ayann’s experiences of Islam as a child have a few basic similarities to the American Evangelicalism of my childhood. In making this comparison I do not want to downplay the injustice Ayaan experienced as a Muslim woman – something, of course, that I have never experienced. That is to say, I did not experience the lack of individual freedom she did. Nevertheless, a boy growing up in American Evangelicalism in the 1990s could also vividly know the fear of hell, or for most of us in those days the fear of being “left behind.” I can still easily recall scenes from my young imagination of my family’s clothes strewn in piles on the ground due to the rapture. For some reason I always assumed I would not be taken on the first round and would certainly have to suffer a bit longer than others for my sins. How would I fend for myself in their absence? I had few practical survival skills and no guns. This was also the era of purity vows and a push for abstinence. Fear of hell and Evangelical sexual ethics proved a powerful concoction that fueled a yearly cycle (liturgy if you will) of consistently surrendering my life to Jesus each Fall and Summer at Youth Camps. Finally, I can also relate to Ayann’s lurking doubt of the resurrection of the dead. As a teenager I can remembering reading Paul’s letters and being quite taken back that the early Christians expected Jesus to return in their lifetime. How long should we keep waiting?

In the first paragraph of Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s essay, “How (and Why) I Became an Infidel”, she describes a number of social relationships and responsibilities which prevented her from initially leaving her faith. Even in the way that it is phrased, it seems that Ali was an atheist long before she was able to fully make the transition out of Islam. As she describes it, her sexual desire and her subordinate status under her husband eventually led her to escape altogether. Once in the Netherlands, she found solace in the ideas of European thinkers. Though she meant to reconcile Islam with their ideas, she felt that the events of 9/11 forced her to make a choice about whether to support Islam and that terrorist act as the will of Allah. After reading The Atheist Manifesto, Ali describes her relief and clarity at admitting her atheism to herself. This transition was not without its challenges, as she had to come to grips with what would happen to her after death and with choosing her own morality. She concludes her essay with the assertion that there is “no cognitive dissonance in atheism”, even as life remains nonetheless ambiguous.

Ali’s essay is emotional and visceral, especially for those people who can sympathize were desire to remain a apart of the community she had grown up in. I feel that desire too and wonder what kind of choice I will make about how to relate to both my Christianity and to the Christian communities that I have been a part of. That sense of relief that she felt in rejecting the supernatural is also something that I have felt. However, it is pointing out that there are no easy answers for death and for morality in atheism, either. I certainly agree that life remains ambiguous and that there are certain forms of behavior, such as those in which one partner dominates another, which should be excluded. The task of rationally justifying such an ethic now falls to all of us who would reject superstition outright. However, we must still contend with the potential insights that religion might offer, even if it takes a great deal of work to untangle them from a too fantastical cosmology.

In, How (and Why) I Became an Infidel, Ayaan Hirsi Ali gives readers a detailed account of how she transitioned from a pious Muslim into an outspoken atheist. She notes that, from childhood, the tenets of her faith consistently seemed incongruent with her own ideas concerning justice and tolerance. Describing her personal rebellion against her religious community, Ali outlines fleeing from an unwanted arranged marriage and seeking refuge in a largely secular society. She begins her new life merely questioning her beliefs but describes how she ultimately abandoned Islam, intentionally neglecting to replace her faith with an alternative religious practice.

In this piece, Ali’s unapologetic vulnerability invites a unique sense of empathy and identification. For instance, although I do not know or understand what it means to live in a culture where female genital mutilation and arranged marriages are a normative practice, Ali’s examination of the guilt that often accompanies questioning the dominant religious tradition of one’s culture as well the internal conflict that stems from defining and accepting one’s sexuality in a hostile environment speak to my own experiences growing up as a skeptic in Fundamentalist Christian circles. Perhaps more striking, however, is her emphasis on the value of personal accountability in living an honest and meaningful life while divorcing oneself from theism. According to Ali, “living without God [...] means accepting that I give my life its own meaning.” Ali asserts that a life dedicated to the will of God inevitably means the suppression of all personal will and desire. Such a life lacks both individuality and a personal ethic. This is precisely the existence she rebels against and why I find her writing to be deeply compelling.

In Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s autobiography, Infidel, Ali stands in opposition to her male dominated, extreme Islamic upbringing. Ayaan Hirsi Ali explores her pilgrimage to atheism, her journey to becoming an infidel in the gaze of Allah and the rest of Muslim culture. Ali notes her early existential fulfillment to love Allah and be a good daughter for her clan. Submission to Allah, in Ali’s words, means to be in submission to one’s father, brother and husband. The fear of hell further instilled these Somali-male dominated values. Ali expounds, “the Koran lists Hell’s torments in vivid detail: sores boiling water, peeling skin, burning flesh, dissolving bowels. An everlasting fire burns you forever for your flesh chars and your juices boil.” (Hitchens, 584) Escaping the Muslim clan societies of Somalia, Ali is a political refugee in Holland. Exposure to philosophy, western culture and love began to slowly dismantle Ali’s Allah-centric worldview. It was not until the event of 9/11, done in the name of Allah, that Ali felt the necessity to choose a side. Ali’s journey to atheism, infidelity, results in self-acceptance and giving one’s own meaning to life.

Atheism as a reaction to a cultural upbringing is a fascinating phenomenon within the previous 200 years, (I am unaware of recorded cultural reactionary atheism prior to the enlightenment). One’s argument to abstain from theism due to a cultural abuse of power conveys the truth of experience. If one’s god is unable to do just or side with liberation, then what need does someone have for such an abusive deity. Too often within a reason centered framework, the experience of one’s lived truth is ignored. A truth that is unlivable/abusive is an abstraction of what it desires to be. I sympathize with Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s experience.

|

|

|

Elizabeth Anderson |

The title of this text is from the famous words of Dostoyevsky, “If God is dead, then everything is permitted.” Elizabeth Anderson insists that even if there is no God, human being can be moral. In terms of “the moralistic argument” and “extraordinary evidence”, she criticizes assertions of theism, especially Christianity and Judaism. Anderson rejects theistic accounts of morality, then claims that moral knowledge springs not from revelation but from people's experience. She also criticizes various aspects of theism, such as evidence of existence of God, presence of evil, fundamentalism, cruelty of God in the Old Testament, and other doctrinal issues. And she suggests her perspective on issues of moral embarrassments of Christianity, both good and evil teaching, and ascribing of evil in the Bible. To conclude, Anderson says “The authority of moral rules lies not with God, but with each of us.”

In this text, Elizabeth Anderson shows a fairly plausible criticism on Christianity. Though She denies all kind of theism, it is clear that the target of her criticism is Christianity. To my surprise, she cites a lot of texts of the Bible. However, I think her approach on the Bible is too literal. Nonetheless she criticizes Christian fundamentalists, she also commits same mistake. For literalism has been the most critical issue of exegesis in Christian history, I think that keeping a balance between literalism and allegorism is very important. The Bible is not just a textbook of morality or a technical manual for good living, because it contains various aspects of human lives as well as theological insights and testimonies. In addition, I think she misunderstands about revelation, judgment, and satisfaction. Notwithstanding her accounts in text is not convincing at all to me, her criticisms of literalism and historical wrongs of Christianity are worthy of mention.

In this short treatise against the “God of Scripture” and his followers, Elizabeth Anderson concisely yet systematically deconstructs perceived religious fallacies that propagate humanity's most heinous atrocities. Her writing style is intellectual and direct, if not blunt at times. In opposition to globally recognized beliefs that it is faith by way of religion that holds society together, Anderson submits it is community, a sense of living together in cooperation, that is the societal adhesive. She writes, “We know the basic moral rules-that it is wrong to engage in murder, plunder, rape, and torture, to brutally punish people for the wrongs of others or for blameless error, to enslave others, to engage in ethnic cleansing and genocide…” (335). While Anderson praises moral arguments in Scriptures that align with the aforementioned moral rules, she ultimately denounces religion and distills it to a pernicious farce founded on a scapegoat mentality and perpetuating mostly evil and wickedness in this world.

Anderson's aptly named piece reminded me of the passage in 1 Corinthians 10 that states, “Everything is permissible, not everything is beneficial.” I found this verse in between youth group bible studies and my illicit practice of masturbation. What did this verse mean? As an evangelical theist, I believed in God's manifest action in the world and acted in accordance the will of God as it was preached to me. This was the beginning of my developing a layered theology-theology organized according to importance. In step with Anderson's analysis, I began to choose scriptures like a Rorschach test: “which passages people choose to emphasize reflects as much as it shapes their moral character and interests” (341). As a changed my major to sociology, my faith also shifted to the macro. Justice and living fully so that my neighbor could live fully was and is paramount. In light of this, my little acts of perceived sexual immorality weren't that big a deal. Or were they? Are they? Anderson purports that we have individual agency and keen rational abilities, yet we need life together for survival. Now, I'm married. Now, I have a child. Is my individual sensuality and sexuality a weapon of mass destruction? Is it as acetone to the social glue? If not beneficial, it is permissible, right? At what cost? If not for my religious upbringing, would I even be asking these questions? How does my porneia affect future generations? Is it in step with nature or evolutionary biology? Anderson's logical understanding of the world certainly seems to simplify things. Stick to the real and big things.

Elizabeth Anderson weaves an argument for atheism by tracing and flipping two traditional theist attacks against atheism. The first and arguably more culturally entrenched argument against atheism is the morality argument. Simply put, atheism is the source of humanity's ills, massacres, and general moral ineptitude. In contrast, theism, by which Anderson means the Abrahamic religions, is the source of morality, with its moral authority resting in God. The secondary argument against atheism concerns proving God's existence, which itself is dovetailed with the morality argument. If God does not exist, does morality matter? God must exist because morality does. Rather than defending atheism against the morality argument, Anderson subjects theism to the same test, querying whether fundamentalist renderings of biblical inerrancy and competing liberal interpretations of the biblical account of God and God's morality can withstand the scrutiny of modern moral standards. Anderson argues there is much in the Bible that is clearly reprehensible, such as the genocides of the Old Testament, Paul's scapegoating of Jesus under God's judgement, and the apocalyptic destruction promised in the New Testament. She also notes much that is good from the Bible, notably its progressive ordering of land usage and usury to benefit the poor. Fundamentalist theologies fail the morality test for Anderson because they cannot clearly acknowledge and distinguish the good and bad morals from the Bible. Liberal theologies escape that criticism but fail to convince Anderson due in large measure to the inconsistencies of theism's source material. Anderson argues that the contradictory messages of theism (and all religions) are the result of humanity's psychological drive to make sense of meaningless suffering. Not only are the moral arguments all religions make the same pan-culturally, but so too are their claims for the existence of their particular God(s). The moral argument alone destabilizes their source material, which in turn destabilizes their already shaky claims for the supreme truth of their particular religious systems. In place of religion-centered moral authority, Anderson wants to create a system of reciprocal human moral claims, for which atheism is well suited. The moral argument then is not the bulwark of theism, but the province of atheism.

Anderson's arguments against fundamentalist moral interpretations are trenchant critiques of western theism. Similarly, her preference for a human-centered, reciprocal-claims-based morality is promising and in line, at least rudimentarily, with most forms of western, democratic social contract theories. I have two objections to Anderson. First, simply because one rejects inerrancy, must one also discard the whole of religious texts? Religious texts are about so much more than moral authority or proving the existence of God, both of which are primarily modern, western preoccupations. There is much within orthodox Christianity that struggles deeply with the seeming moral ambivalence and absence of God without tripping over fundamentalism. Robert Neville is a theologian who embraces the ability of broken of religious symbols to convey ultimate meaning. One need not refute all religious symbols when one renounces inerrancy. My second objection is in regard to the adequacy of human-based morality (and really all morality, including God-based morality). Take for instance Herman Melville's Moby Dick, in which the predestining God of Calvin is placed alongside perilous nature in the form of the whale, whose inscrutable malice dashes the Pequod as if it were no more than a fly. For Melville, morality is not the province of God. Rather, morality is left in the hands of the Pequod's captain and crew, who fail to live despite all of their moral claims upon each other. Starbuck's entreaties, Pip's death, or even Ahab's duty to the shareholders of the Pequod are enough to restrain Ahab's quest. Are humans ever able to live together morally?

Elizabeth Anderson’s “If God Is Dead, Is Everything Permitted?” articulately addresses that the fundamentalist rejection of evolution is based on what they perceive as the moral repercussions of the argument rather than the science of evolution. She identifies the discomfort theists have toward atheists as the fear that without God, there can be no morality. Anderson argues that theism causes more grounds for immorality than atheism, then goes on to define what she means by theism and makes her case with strong arguments supported by scripture. She agrees with Kant’s categorical imperatives, but leaps from a rejection of Biblical literalism to a rejection of the Bible as a whole. She critiques religion’s truth claims because they are not upheld by the scientific method. Anderson concludes by stating that we as individuals have the authority to create moral rules through reciprocal claim making (346-347).

I really enjoyed Anderson’s argument. It was delivered well and maintained a cool rational quality despite the fact that she was clearly offended by the charge of immorality given to atheists. While I believe it was necessary for her to turn the tables on her accusers, I didn't buy her entire argument. There is a need for believers to keep their religion from being co-opted for injustice, just as all citizens have the responsibility to keep their secular government from power corruption and immorality. Theists and atheists both have the responsibility to keep power from corrupting their morals. Although I agreed with Anderson’s logical assessment of morality as reciprocal claim making, I do not believe it has to be so reductionist as to only work on a secular basis. Believers believe for a reason, many because of their personal religious experience, but Anderson never addresses why believers might want to believe in addition to the morality they perceive their religion brings. Her argument would be strengthened if she gave theists a way to check the morality of their own religion.

Elizabeth Anderson seeks to answer, and deny, the claim that without God we would descend into rampant immorality. Anderson flips the argument on its head by showing that theism leads to the belief that heinous acts are moral. To build this argument she cites a variety of passages from the bible that describe God as committing and condoning acts that are universally considered immoral. Since Anderson equates theism with following scripture she concludes that belief in God commits one to an ambiguous morality at best. If theism doesn’t give a morality it is absurd to think that abandoning atheism would lead to immorality.

It is a shame that such an elegant argument hinges on such a shallow understanding of religion. On one hand she seems to say that morality exists independent from theism, yet at the same time she is painting a picture of immorality bound to theism. You can’t have both; and of the two the former is more productive. Sure, you lose the great chance to call religion immoral but you gain the opportunity to explore the actual nature of morality. I can’t really blame Anderson though for just wanting to point out hypocrisy, it’s a great sport.

Elizabeth Anderson presents a convincing argument concerning atheism and morality. She reflects on the question raised by Dostoyevsky, “If God is dead, then everything is permitted.” Her argument is that this cannot be the case because morality comes before religion from the communal experience of humanity living together. Where theism, specifically monotheist and excluding deism, argues that a moral authority is necessary to preserve order, atheism asserts that communal experience provides proper understanding apart from a sovereign “authority.” A review of biblical texts clearly presents a God that is unjust and immoral. Between the vengeful God of the old testament and the harsh words of Jesus in the new testament, religion has no logical grounds to say that God is completely moral. First this would affirm that morality is something set apart from God; God is not necessarily moral in scripture. Even though some extreme fundamentalist might “bit the bullet” here, they still cannot logically claim that morality exists only with God. For more moderate religious individuals Anderson makes the clever argument hat a contemplation of morality should actually lead believers away from God rather than toward one. Since the stories in scripture of God acting immorally must be seen as such, one comes to realize that morality must exist apart from a theistic God. And if God is not necessary for morality, what is the point in belief anyway?

I really appreciate Anderson’s argument here. It is a clever way to justify why morality matters even outside of the context of religion. It seems to me though that she didn’t explore the idea of morality growing out of human proximity though. I understood her argument for morality through the view of an atheist to be primarily enforced and established by the government and a common sense mentality. Of course I should not harm another person because I don’t want them to harm me, seems to be the grounding of the morality she presents. Her argument focuses primarily on turning the burden of sin back to the theist. At the point where we lose an authority completely removed from human experience, we can really appreciate the value of morals. Still, I would question as humanity becomes more autonomous and individual if attacking theist is really the best use of argument. Morality springs from communal interaction. At the point where atheism gives not president or grounding for community, I wonder if theism still has something deep to offer in the community it provides that Anderson overlooks. For the majority of theists, religion seems to provide a point of holding human experience in common. I get the feeling from Anderson that she thinks the world might be more moral without theism. If the world became completely atheistic, I wonder what might bind humanity to the other? Religion gives a framework to see morality in a global sense and a system that confronts many individuals on a frequent basis. If this argument was presented to every child from birth to death, I can imagine the world have a majority of atheists, though I can’t imagine that it would be any more moral than it is today. At the point where an atheistic argument of this sort does not present a more advantages alternative, I wonder why the author really thinks it is important. If it’s for the purpose of attacking those who are immoral in their religion I completely support it, but would imagine it constructed in a different way.

Summary: Elizabeth Anderson starts her essay by first addressing the religious person’s critique of atheistic morals. This is mainly based on the idea that without reward and punishment, there is no moral authority and any system that gives credence to that should not be followed. She then uses the rest of her essay to systematically break down the flaws in this argument. This ranges from Plato’s critique of “Divine Command” theory to biological evolutionary evidence against a grand designer. Anderson spends most of the essay citing multiple evidences from the Bible of how God is morally bankrupt and that if one were to try to say that God is the ultimately line of morality, that morality is unclear and at times very apparently evil. Towards the end of the essay she expands to speaking more broadly of religion in general and how a moral dependence upon God is inadequate.

Critique: I thought Anderson spent a little too much time criticizing evil deeds in the Bible. I kind of saw it as “beating a dead horse.” She brought an abundance of points of why God is evil when I think a lot of the essay could have been better suited addressing how atheism itself can sustain its own moral model. She begins to do it a bit towards the end of the essay but still does not do it justice in my opinion. The phrasing of the title sounded much more like she was going to display a defense of secular morality but she spent most of her time attacking the morality of theism.

Elizabeth Anderson engages a question that many other authors in compilations such as The Portable Atheist tend to merely flirt with: the existence of morality in the absence of God. Anderson begins with a display in a California museum by creationists, which has the “tree of evolutionism,” whose roots are atheism in the soil of unbelief. Their primary attack on evolutionism, Anderson notes, is not scientific but moral. They accuse unbelief of fostering immorality, which leads her to explore this premise further, namely the Divine Command theorist perspective that the word of God dictates morality. Anderson spends pages listing out examples from the Bible that prove this God cannot be the dictator of morality, given the cruelty of God’s moral character revealed in scripture. In light of this, we must turn to something else. Anderson denies the acceptance of other forms of religious moral code via revelation or other extraordinary sources on a lack of credibility. Therefore, Anderson argues, morality must be a “system of reciprocal claim making” (347) to which every person who makes claims about morality is accountable to each other, for we all have “moral authority with respect to one another.” (346)

If any of the essays and writing found in The Portable Atheist have struck me as persuasive, it has been Anderson’s. While many authors in this kind of collection jump at the chance to point out biblical evidence for an unloving, immoral creator, Anderson takes the time to also identify and examine the arguments often made by her opponents, and does so with grace and thoughtfulness. Anderson is clearly on the search for truth that can be validated and proven, which I cannot help but admire, despite my disagreement with her conclusions. It is often helpful, in the piles of scalding and disrespectful literature on these topics, to find a thoughtful writer who wishes to engage in critical thought with her opponents rather than destroy their personhood. Both theists and atheists can learn from Anderson’s writing.

In her essay, Elizabeth Anderson argues that God is not necessary for morality to exist. She contests the notion that atheism inevitably leads to immorality and systematically deconstructs what she considers the fundamental arguments for an ethic predicated on theistic assumptions and beliefs. Her assertion throughout the piece is a very definitive stance is not merely that morality can be cultivated and maintained independent of religion.Anderson contends that the ethical principles that govern society may in fact do better without the input of religious doctrine. At any rate, she estimates that a belief in God does little to trigger or enhance our ability to understand the difference between right and wrong. She concludes by rejecting all forms of theism and supernatural thought, proposing that in its place humanity adopt a system of moral rules whose authority rests within the individual, of which she concedes is not absolute.

Anderson’s approach to arguing this issue works brilliantly because she refrains from demonizing religion absolutely. Although at times she ignores the nuances contained in New Testament texts and interprets its components at face value, she does not exclude from the discussion the fact that religious teachings and texts often contain ethical prescriptions that are beneficial to practitioners and perhaps even the larger society. Rather than deny or ignore them, she insists that these moral teachings exist independently of a divine agent and goes so far as to argue that appeals to a divine authority may undermine their legitimacy. Overall, Anderson offers a fair critique of religion, religious ethics, and the scant evidence for God while admitting her own biases along the way and presenting a viable alternative in the place of faith based moral frameworks.

|

|

|

Alfred Jules Ayer |

In this article, Ayer shares his near death experience. His experience does not incline him ro believe the existence of a supernatural deity. While believing that consciousness does not disappear with death, he refuses the idea of future lives. By presenting views from different atheistic philosophers (such as McTaggart and Broad), he emphasizes his thesis again that there is no God. His near death experience is a result of his brain working even while his heart had ceased to beat.

It is fascinating to see that Ayer mentions Greek mythology in his article. In Chinese mythology, there is also a river of Death. Dead people have to come across the river, drink a special soup that takes their memories away, and be ready for the next life. Why is there always a river in these “what will happen after your death?” stories? Ayer mentions Greek mythology because he wants to prove that he is not ignorant of things that theists might want to believe. I am curious in knowing how he explains the overlap between Greek mythology and Chinese mythology. In my interpretation, the significance of the river in Greek or Chinese mythology is that it represents the hope of a future life. When dead people come across the river, the water flows in them. The river water washes away from them the dust of their former life. They are renewed. If they are able to come across the river, each of them will become a new person. Ayer does not believe Greek mythology because he rejects the idea of a future life. I do not believe it, either. I do not know what is going to happen if dead people cannot pay for the ferryman. What kind of currency does Charon accept? What is the “form” of dead people when they come across the river? If they have bodies, will they drown if they fall down from the boat? If they are spirits, why do spirits have to rely on a boat? I do not think the author(s) of the story can answer my questions. The Greek (or Chinese) mythology is only a fiction.

However, unlike Ayer, I believe there is a future life. I guess every Christian wants to have an enteral life in the Kingdom of Heaven after their death. Claiming that there is no future life is cruel. If I was an atheist, I would not make a statement like this, even though I might think the idea of having a future life is ridiculous. The expectation of a future life is the hope that encourages miserable people to sustain their lives. If they are unable to get rid of troubles in their current lives, they need to know one day (maybe in the next life) that difficulties will be gone. Troubles are not going to stay forever. I do not care whether there is a future life or not. What I care about is how the expectation of a future life functions in a positive way to help people survive from the misery of their lives. Ayer and other atheist have the right to defend their disbelief in having a future life, but they should be careful not to deprive hope from the spiritual world of disadvantaged people. It is as cruel as telling a small child who has been waiting for her Christmas presents for a year that Santa Claus does not exist.

The essay is A.J. Ayer’s retelling of and reflection upon a four-minute arrest of his heart. Ayer describes his vision, while apparently unconscious, of an intense light accompanied by several entities that he mysteriously knew were associated with space and time. Supposing these experiences were not firings of an oxygen-deprived brain—which he later argued was a likely explanation—Ayer reflects on problems that arise with the notion of body-less identities such as an immortal soul. However, Ayer notes that even if there were another world beyond this one, it would, from our point of view, have no more of a necessary relationship with a god than this one and would bring us no closer to revealing anything about God’s existence.

By clearing room (however small) for other worlds, Ayer’s experience could profoundly affect the way we describe our world. If another world or worlds exist radically unlike this world, what happens to our epistemology of possibilities? If our data from this world do not correspond to the truths of other existing worlds, most propositions about our world would be rendered questionable. This would be doubly true if these worlds were linked by the migration of identities from one to another. The small allowance Ayer makes is an admittedly honest turn given an uncanny experience, however its ambiguity later warranted a weakening of his initial statements Ayer doubts that he saw something from another world, but the possibility haunts his readers. Unsettled by how the dark chasm of the possible could spit, spew, or send anything conceivable in our direction, we find ourselves in deep doubt. The night where all cows are black may produce aberrations of probability. Other worlds may be—it is as if Ayer gives permission to possibility as it peers at us through the smallest fissures within our world. In that moment when the possible invades, justification and rationality only do what they can do.

In That Undiscovered Country, the influential Atheistic-English philosopher AJ Ayer retells his experience of death and subsequent resuscitation and explains how this experience has influenced some of his philosophical beliefs. During a hospital stay for pneumonia, Ayer’s heart failed for four minutes. Medically, he was dead. However, Ayer recalls the experience vividly. Ayer recalls experiencing of an intense, bright red-light that seemed to govern the universe. The red-light had two ministers that helped govern space. The two minsters we no good at their job, so Ayer felt it was his responsibility to correct their “fuzzy” errors through his manipulation of time. However, before Ayer was to affect any change he woke from his experience. As a philosopher, Ayer has since reflected on his experience. First, he concludes that the most probable explanation for his NDE was that his brain continued to function in some sense while his heart stopped. Next, he considers how such a life-at-death could be possible. Ayer concludes that personal identity necessarily requires one or more bodies through time that a person might occupy. Therefore, any personal identity after-death must be bodily. Lastly, even if there is such a future life, it would not prove the existence of god. Since, according to Ayer there are no good reasons to believe god create presides over the present world, there is no good reason to believe that god presides over the next world. Ayer concludes with these words, “So there it is. My recent experiences have slightly weakened my conviction that my genuine death, which is due fairly soon, will be the end of me, though I continue to hope that it will be” (275).

Ayer’s piece offers some interesting reflections on NDE and what life-after-death must be like, if there is such a future existence. First, it is refreshing for a philosopher of Ayer’s caliber to talk about personal experience that become part of one’s evidence for religious belief. I think too often analytic philosophers act as though personal experiences are not involved in rational discourse because, then, not everyone is working with the same evidence. Richard Feldman’s epistemology reminds me of such a stance. On the other hand, personal experiences seem to be an important factor in what people find rational and irrational. Second, Ayer’s point that a justified belief in the existence of an afterlife does not justify one’s belief in god is thought provoking. This might be true. Of course, I would push back and want Ayer to describe what kind of afterlife he has in mind. It appears all that Ayer is willing to say is that existence after death requires at least one body—he recommends putting your personal make up of atoms. It seems that such a “putting back together” of atoms to make each person is like putting a puzzle back together. If this is the case, it doesn’t appear that nature could do this, even if one believes in a completely naturalistic version of the “putting together” of humans. Putting back together seems to requires some kind of intelligent agent. However, I agree with Ayer’s point but would want to add that when thinking about the existence of god in relation to arguments of an afterlife, one must explain what he or she means by “afterlife.” Whose afterlife? Which afterlife?

|

|

|

John Betjeman |

The quick, personal, self-centered prayer of a churchwoman is portrayed tongue-in-cheek in rhyming verse by Betjeman. First she prays for God to bomb the Germans but to spare their women if possible; if God cannot do this, she says she can forgive Him. Then she shows racial bigotry in asking protection for allied troops, especially white ones. She lauds her country and asks for “special care” for her home address. She smoothes over her own sins, and seems to offer her service to God if God will grant her petitions. She takes a moment to look toward heavenly reward for her service in the warless “Eternal Safety Zone,” before she decides she needs to get on with her life and make it to a luncheon. She leaves feeling a little better, feeling she has heard God’s word in her time at Westminster Abbey, when she has only heard herself.

Theists and atheists alike can be amused by Betjeman’s clever humor. Taking personal prayer to an extreme, he truly indicts many a Christian or supposed Christian whose faith or prayer-life is more ego- than theo-centric. Certainly this parody would have been equally fitting for many American churches in the wake of the September 11th attacks, when it was so easy for American theists to presume that the God of America was on their side, reducing (or rallying?) this God to a tribal God rather than a universal creator. Christians ought not be blindsided by the inappropriateness of this attempt to use or manipulate God. The Catholic Church emphasizes the transnational (and trans-temporal) community of saints such that personal prayer ought to be addressed to Our Father. Protestant psychologist Larry Crabb reminds Christians not to pray simply out of their needs, felt or real, because prayer “is not about making our life on earth as comfortable as possible, nor praying for everything to go right; it is about us coming to God as we are and relating to Him” (see A. Mozombite, “Larry Crabb: The Papa Prayer”). Betjeman succeeds in showing a form of personal prayer which is inappropriate and ridiculous.

In his satirical prayer written in 1940 England, Betjeman tells the prayer of a woman requesting of the Lord many trivial actions. She provides first an opening to the prayer, and quickly asks the Lord to bomb the Germans. Being written in 1940, it is difficult to imagine that this was not a direct attack at prayers that Betjeman might have heard firsthand. She then requests that He spare German women, but assures that if it not done, they will forgive the mistake. Only so long as she is not bombed herself. She then prays the prayer of all great nationalists, “Keep our Empire undismembered Guide our Forces by Thy Hand,” and for the protection of the blacks in Central America, but “even more, protect the whites” (p. 168). This woman in prayer goes on to agree that she will attend Evening Service, given that her schedule allows. But even this must be good enough, for she asks the Lord to reserve her a crown and protected finances. By the end, she rushes out of her prayer to make a lunch date.

It is nothing short of ridiculous to assume that Christians cannot laugh just as quickly as atheists at this unsettlingly accurate portrayal of Christian prayer. Growing up in the conservative evangelical South, I’ve heard many prayers that might not be so explicitly prejudiced, but I’ve heard my fair share that anyone with a third grade education could understand as simply selfishness. However, I am not one to subscribe to the thought that any good criticism of an action or organization demands it to be shut down altogether. Instead, it ought to bring about critical reflection and reform to how Christians understand and practice prayer. While we work to improve our relationship with the Divine, atheists can continue to gather, laugh about how stupid we sound, and write more wonderful satire. That’s fine with me.

Chapman Cohen is trying to establish atheism at the base of Monism. He emphasizes the importance of the individual in todays society. About the Monistic view of the individual, Cohen describes that it is utterly devoid of the dynamic which can generate any great social reform. And about the relations of the individual to society, he concludes that the society is not a mere aggregate of individual human beings but more powerful one, with examples of an army and a chemical compound. According to Cohen's opinion, society and the individual can not exist without each other. In this manner, he criticizes the individualism of Christianity, and deal the individual and society in terms of Monism.

Cohen's accounts in this text are political and sociological rather than religious. He criticizes theism and Christianity for their excessive undue emphasis on the individual. I feel that he regards that kind of individualism as a primary cause of modern social problems. I can partially agree with him for the historic example of the medieval church, because people merely believed salvation of individual soul at that time. However, the reason why I cannot totally agree is, Christianity has its social vocation. Human being who experienced salvation in the grace of God, will become a better individual, and will try to make a better society and world in the love of God.

Cohen's accounts in this text are political and sociological rather than religious. He criticizes theism and Christianity for their excessive undue emphasis on the individual. I feel that he regards that kind of individualism as a primary cause of modern social problems. I can partially agree with him for the historic example of the medieval church, because people merely believed salvation of individual soul at that time. However, the reason why I cannot totally agree is, Christianity has its social vocation. Human being who experienced salvation in the grace of God, will become a better individual, and will try to make a better society and world in the love of God.

Chapman Cohen was a man of his era, an age awash in scientific and evolutionary thinking. His worldview reflected the new paradigm in that it criticized theism in the face of monism, which disallows both the differentiation of fundamental parts of reality and the necessity for some sort of interfering or guiding divine principle. Cohen argues that monism, as well as beliefs such as Spinoza's pantheism, ultimately qualifies as atheism due to its denial of personal theism. With these ideas as his foundation, Cohen's piece focuses on the nature of the individual and society through Christian and monistic lenses. Facing theological criticism of monism as dooming the individual, Cohen writes that the individual is not and cannot be lost because it is an integral part of the greater societal system. He states, “We do not annihilate the earth by showing its place in the solar system...” (173). It is impossible to discuss the individual outside the context of his or her history, social situation, etc. just as it is impossible to discuss a society without knowing the individuals that make it up. He expresses this quality with the term “sociological atomism” (173), which roughly translates to the modern integral philosophers' phrase, “transcend and include.” Cohen refutes the Christian belief that morality is grafted onto the individual by pointing out the many moral flaws of the Christian church throughout its history. Instead, he writes that morality is defined by societal forces which work themselves into the individual. Essentially, the good of the group will equal the good of the individual. These societal forces, though, are not some “mysterious social ego” (174) suggested by religion, but are in fact just as much of a product of individuals as an individual is a product of his or her organs. Finally, Cohen ties it all together by stating that the individual is not the product of some supernatural origination, but a “necessary result and expression of social forces always in operation” (176).

As far as Cohen's ideas on the individual and society go, I find little to disagree with. To believe that a society is simply the sum of individual, all-wondrous human beings is silly. Cohen is absolutely correct in removing humanity from its peak upon the universal scale of importance, though I highly doubt his argument would have any traction on those of faith who hold humanity's divinely ordained centrality as their core principle. On the other hand, I find significant fault with the underlying nature of Cohen's arguments. His place in history contributes to both his fervor and his blindness. Coming up in the age of evolution and scientific discovery has created in him a worldview that accepts everything as a causal process that can be, in time, scientifically studied and analyzed. Thus his presentation of the individual and society has taken evolution and its tangential implications as complete and unalterable facts, quite the danger for a truly inquiring scientific mind. Even more dangerous, though, are the applications of this worldview to the monistic reality Cohen attempts to promote. He writes, “If there are any gaps they are in our knowledge, not in things themselves” (170). Now, certainly there are truths to this claim and it is a very potent critique of those who wish to establish a “God of the gaps” theory. However, as more sober reflections on the theory of evolution and modern discoveries about the nature of fundamental reality have emerged, his argument has the stains of scientism. In sum, this essay shows Cohen as both a brilliant sociologist and a short-sighted scientist.

Cohen discusses the ubiquity of narratives of gods intervening in births. In light of this, Jesus’ birth is highly unoriginal. Cohen asks: “What is the meaning of it all? Why were all these gods and demi-gods born in this manner?” “Commonplace” trivialities mixed with superstition, he answers (178). But what about scientific discoveries? He feels these should eradicate our superstitions. Death and birth, for example, were once conceived through superstition. Then came biology and we understood the reality of procreation in a purely physical way. Regardless, people still want to hold to the virginal conception of Jesus. Thus “all religion, no matter how refined,” has “its roots in the delusions that have their sway over the mind of mankind in its most primitive stages.” We want to believe in the supernatural births of a few special people. Hence Christianity’s ‘virginal conception.’ But Cohen reminds his readers that the “savage” mentality is the foundation for such beliefs. Thus we should consider the “psychology of religion” and focus on how people “came to believe” in these kinds of superstitions (180). In this way we may overcome our superstitions.

Cohen’s point is certainly worthy of consideration. No doubt the narrative of Jesus’ virginal birth is not unique to Christianity. In fact, I’ve recently read varying accounts of the birth of the Buddha Siddhartha Guatama. Lots of parallels. The only point of criticism I offer is that Cohen doesn’t explain why beliefs about gods intervening in births is problematic. He only shows that people from time immemorial have held such beliefs. But why does this fact negate the beliefs? Simply by appeal to lack of Enlightenment-Rationalist-Empiricism? This does not convince me to shed my “superstitions.”