Corrymeela, a Community of Forgiveness

By Erin Beary

For Theology I (Dr. Wildman)

November 14, 2001

Corrymeela is a dispersed Christian community of reconciliation. There are 180 members, Catholic and Protestant, who commit themselves to search together for the path of peace, as they discover what it means to follow in the footsteps of Jesus.

In all our work, Corrymeela seeks to establish a "safe place" where people feel accepted and valued. During a stay at Corrymeela, a person is invited to become part of a "community" that transcends the divisions, which are so powerful in much of life in Northern Ireland. In a secure atmosphere, there is an opportunity to grow in understanding as we listen to one another’s life experiences. We find that "listening" to others, and "telling" our story is a way of growing closer together, and of discovering the vulnerability and humanity of the "other." We find that such an experience can face a person with new choices for their future, as prejudices are uncovered, misunderstandings corrected, and fear is replaced by trust.

— Timothy Kinahan, A More Excellent Way: A Vision for Northern Ireland

Introduction

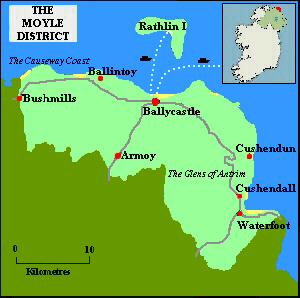

My deep interest in Northern Ireland is from an unknown source. In part, I know that I was deeply affected by the stories of both frustration and reconciliation that my friend, Jenny, told me after her return from a summer volunteering at the Corrymeela Community. However, Jenny’s parents are from Ireland, her roots are there. Perhaps my heart is there for a reason that will soon be revealed. I am planning on completing my Field Education in Northern Ireland next summer and would like for six of the ten intensive weeks to be spent at the Corrymeela Community near Ballycastle, on the Antrim Coast (see a map of the area, below). I spent four amazing days in Northern Ireland last summer, talking with some of the key players in the ecumenical movement while planning for my Field Education program. I spoke with Trevor Anderson, the Director of Corrymeela at their office in Belfast, I spoke with Johnson McMaster, the Director of the Irish School of Ecumenics who offered to be my mentor next summer. I also spoke with David Stevens, the Secretary for the Irish Council of Churches, and this is only listing a few!

The Corrymeela Community (see the photograph of the Corrymeela Center at Ballycastle, below) that is located on the Antrim Coast is a retreat center which hosts groups and conferences from all over Northern Ireland and the world. Most of the year is spent with different types of groups, including youth, and the summer is spent hosting families who have been affected by the Troubles either financially, by violence, or both. The staff has extensive programs for the youth of Northern Ireland who are raised in religiously segregated schools throughout their lives until university. Catholic and Protestant youth are further divided because they are even raised playing different sports. While I was in Northern Ireland, I was fortunate enough to visit an integrated school called Shimna Integrated College, but it is a vast minority of schools. Shimna still deals with segregation to some extent because religious education is in the required curriculum and the children must be separated for at least that one class hour per day. Corrymeela tries to create a space of trust and love for these children who don’t know each other and yet are raised with preconceived notions about what the other stands for and believes. Corrymeela is simply a place of refuge for Protestants and Catholics of all ages and walks of life to exchange their stories.

Corrymeela Center [copyright 1997, CAIN]

It has been said that the conflict in Northern Ireland is among the most heavily analyzed conflicts of modern times. The writings of the founders of Corrymeela indicate that some time after the beginning of the Troubles, they felt as if they were lab specimens under a microscope. Now, I feel as if I am doing the same thing – analyzing this amazing ecumenical community that is a credit to the country of Northern Ireland and a benefit to the world. However, in this paper, I will examine only a small slice of the Corrymeela experience: forgiveness.

The ultimate goal of the project at Corrymeela is the reconciliation of the divided peoples of Northern Ireland. On a more theoretical and global level, this is also the goal of the evangelical Protestant theologian, Miroslav Volf, in his book, Exclusion and Embrace: A Theological Exploration of Identity, Otherness, and Reconciliation. I will use the author’s interpretive categories in both social and theological reflection in order to put the conflict in Northern Ireland into this particular perspective. The general framework of this research will be structured such that we will first examine the socio-historical context of the conflict as the backdrop for the innumerable sufferings endured by the Irish people, both individually and collectively. Then, I will develop Volf’s theological standpoint with particular reference to the Troubles. This paper will analyze the concept of forgiveness through Volf’s metaphorical lens of exclusion and embrace. Finally, we will examine Corrymeela as a catholic and ecumenical community, as Volf describes these terms and from that vantage point, it will be possible to see the efforts of Corrymeela as a beautiful practical example of these theoretical ideals.

Corrymeela Welcome Sign [copyright 1997, CAIN]

As already stated, the goal of both Volf and Corrymeela is ultimately for the reconciliation of divided peoples. Given the very focused nature of this paper, it would be impossible (as much as I would desire it) to do a complete theological analysis of Corrymeela with respect to all of the components of reconciliation in the framework of Volf’s work. So, this is a small warning that many terms and issues that are fundamental to discussion of peace and reconciliation will be touched upon only lightly.

As mentioned, I will begin with the historic origins of the conflict in Northern Ireland, with its religious and political backdrop. The history will be a very broad overview, as a whole thesis could be written on this one aspect of the Irish history alone. From there, I will examine the situation from the perspective of a social analysis, taking a brief look at the instrumentalization of the church for political ends. The socio-historical analysis will give the underlying context for the human condition as it appears in light of the Troubles. Then, with a better understanding of the human condition as revealed in Northern Ireland, the theological analysis will be of utmost import, as it is one response of Christian kerygma to the problem of human suffering. Volf’s notion of catholicity will be introduced, keeping in mind the instrumentalization of the church, as examined in the social analysis. At that point, there will be more elaboration on how Corrymeela fits into Volf’s understanding of exclusion and embrace. Finally, an involved examination of the complexity of forgiveness as applied to the situation in Northern Ireland will make the overlap between Volf’s concept of embrace and the Corrymeela vision even more apparent.

Socio-historical Context of the Northern Irish Conflict

Part of what makes the divisions in Northern Ireland so overwhelming is that their origins go so far back in time. When people talk about trying to reconcile the divided peoples of that country, they are not talking about a people who have been divided since the Troubles began in the late 1960’s. Unfortunately, to examine the roots of sectarianism in Ireland, we must revisit the Protestant Reformation in the 16th Century. Dr. Joseph Liechty argues that there are three main themes which establish the background for sectarianism in Ireland. First, the Anglo-Norman conquest of Ireland began during the reign of King Henry II in 1171-1172 A.D. This was an extremely bloody endeavor and this bloodshed was the foundation of relations between the two peoples. Second, the consequences were so much more devastating for the Irish, on whose soil the battles were fought. Third, the Anglo-Norman conquerors looked down on Irish culture as being backward, uncultured, even barbarous. It was this perception of the Irish that allowed the English to justify their attempts to "civilise and Christianise" the Irish after the Protestant Reformation.

It is immediately obvious how religion and politics initially became so intertwined. The indigenous people and Catholic majority became politically and religiously oppressed in their own land. The English took advantage of their superior military might to use Ireland to their economic advantage as well. Protestant plantation had been used since the mid-16th Century to gain access to land and the political upper hand. This caused further dispossession of land for the disgruntled Catholics, and the so-called Ulster Plantation, settled in 1610, saw much bloodshed because of it. Such plantations did nothing to integrate the English and the Irish and only served to foster mistrust between the two.

Fast-forwarding approximately three centuries, to the year 1921, much political wrangling caused Northern Ireland to become a country of six counties, separate from the home-ruled Republic of Ireland. The protestant (English) minority was still the ruling power as King George V opened the first Northern Ireland Parliament in that year.

Dissent continued to grow in the next forty years and Protestant Unionist (notice the linkage of terms) leader Terrence O’Neill became prime minister of Northern Ireland in 1963. He came under serious opposition from within his own party and from without. The conflict heated up as differing factions of Catholic Nationalists and Protestant Unionists became more and more militant in their sectarian divisions. It is in this context that the Corrymeela property was purchased on the Antrim Coast of Northern Ireland in 1965. Only three years later, the Troubles began.

The social ramifications of such difficult historical developments are disturbingly apparent in Northern Ireland. Though Miroslav Volf wrote Exclusion and Embrace in the context of the Serb-Croatian conflict in Yugoslavia, his sociological categories hold very well for our purposes. Volf admittedly places the idea of "identity" (particularly with respect to "otherness") at the center of his theological analysis of reconciliation because he sees identity and otherness as the underlying factors in the ethnic cleansing in his homeland. This is also a good starting point for our purposes because the two themes can be seen at the center of the conflict in Northern Ireland. To start, it must be stated that boundaries between people enable groups to form and maintain identity. These boundaries can simply maintain identities or they can be used to exclude those of another identity, creating the mindset of "Us" and "Them." In defining who we are, we, either implicitly or explicitly, define who we are not. In this way, we define the "other."

The term that Volf chooses for such separate group identities is "tribalism." This, in fact, is the same term that the Irish choose as well. Volf defines "tribes" as "particular cultures which provide a matrix for the emergence of the self… in situations of conflict, a given group identity can become a terminal identity, subsuming under it and integrating a whole range of other identities; each member of the group must completely identify with the group." The author maintains that tribes will always exist, despite the presence or absence of conflict. Ray Davey, the founder of Corrymeela, describes one incident where this notion of tribalism was overtly apparent even in this community of peace. The retreat center was hosting a religiously mixed youth group who had never met each other and two Catholic youth arrived, knowing very little about the community and its values of dialogue and acceptance. The two youth showed up at Corrymeela, wearing the Irish flag boldly on their shirts and vehemently proclaiming their political and religious beliefs. As Davey describes the experience, it took the teens several days before they felt comfortable enough to put their "tribal" garb and language on the shelf and approach the others with the hope of making a human connection with them.

Due to the nature of the conflict in Northern Ireland, Church and even God were dragged into the tribal identities of the factions. The conflict became so complex that it is difficult to distinguish Protestant from Unionist, Catholic from Nationalist; the identity terminology overlaps so much as to be almost interchangeable. Religious identity and its unhealthy association with political leanings were used readily to garner support for political ends. This instrumentalization of religion is made possible, according to Volf, because of the churches’ destructive commitment to the preservation of culture. Ray Davey states it this way; "In Ireland we have interned God in our own traditions. He has been reduced to a tribal deity – the God of the Protestants or the God of the Catholics… We have privatized God and used him as a means to further our own interests and those of our tradition." He describes one Protestant visitor to Corrymeela as having spoken a word of God’s blessing to a worker and upon being casually informed that the worker was Catholic, she rescinded her comment. Asked why she would do such a thing, the visitor explained that her God was different than the worker’s. From this example, it is apparent that tribalism informs not only one’s own identity, but also the identity of the other, and even the identity of one’s God.

Though the Troubles have seen some relief in the past ten years, those tribal identities are still touted in Northern Ireland. As I drove through the towns and villages last August, it was impossible not to notice the Ulster Volunteer Force and Ulster Defense Association flags flying high in many Protestant neighborhoods and the Republic’s flag tauntingly waving over the Catholic areas inside the so-called Peace Wall in Belfast. However, there are things even more disturbing than political flags identifying religious communities. As recently as September 3 of this year, we read in the newspapers that Protestant militants threw bombs at a police line near Catholic school children on their first day of school. I had departed from Belfast only four days prior to the event and when I left the city, I, like the Irish, had been lulled into a false sense of complacency about the urgency of the situation. Perhaps through complacency, perhaps by turning a blind eye, Northern Ireland somehow has learned to sit in uneasy rest with the violence of its people.

The disappointments of history and society, tribalism, and the instrumentalization of religion, to name only a few, shape the realities of the human condition revealed in Northern Ireland. Several aspects of these realities rear up at us from the situation in that small country. First, there is a reluctance to repent for violence and atrocities, and a reluctance to forgive such deeds. This, in particular, only serves to foster mutual exclusion and deepen the barriers of mistrust between tribes. Second, there is a cycle of violence which is yet to be completely broken, each group justifying its use of violence by considering it to be "just" revenge. The violence is perpetuated in a battle of "just" revenge as response to perceived "unjust" revenge. Third, tribalism and the extremes of identity and otherness encourage each group’s dehumanization of the other, which then reinforces the reluctance to repent and forgive, and the cycle of violence. Finally, Volf describes two kinds of suffering that exist in such violent situations: the suffering of the victim and the suffering of forgiveness. This refers to the suffering incurred by the victim due to the crime itself. The suffering of forgiveness has to do with a situation where the victim chooses to forgive the perpetrator of a crime and no "true" justice is done. The suffering of forgiveness is that suffering which is fostered by the forgiveness of a perpetrator of violence who may have never repented and has definitely not been adequately punished for the crime. Although listed in a particular order, I would suggest that the previous four elements really co-exist, rather than arise in any sort of order.

On the first point, the lack of repentance and forgiveness, it is no wonder that victims of crimes are unwilling to forgive. In many cases, they or someone that they love has been injured or killed by a member of the other tribe. No amount of repentance or justice will undo the crime. This problem of the irreversibility of deeds and their consequences contributes heavily to the problem of forgiveness. Volf suggests that it would almost betray our sense of justice to forgive the perpetrators of such crimes – that it would really be unjust to forgive. This seems particularly true in the frequent cases where the perpetrators of such crimes are unwilling to admit to the moral wrongdoing and offer repentance for their acts. This mutual mistrust serves to deepen wide chasm that already exists between the two tribes. A Catholic woman at Corrymeela told of her response to the shooting of her son by British troops in Belfast in 1972, when the fighting was very heavy. She says, "Well, I couldn’t forgive… It’s only lately that I stop myself from shouting at [the British soldiers] in the street. I still don’t like them, but now I turn my back to them. I don’t know about this thing forgiveness."

This brings us to the second point, which is the deepening cycle of violence. Volf argues that this cycle is engendered by an imbalance in the perception of the social actors with respect to the moral implications of their actions. The author describes it in this way: "When one party sees itself as simply seeking justice or even settling for less than justice, the other may perceive the same action as taking revenge or perpetrating injustice. As the intended justice is translated by the other party into actual injustice, a ‘just’ revenge leads to a ‘just’ counter-revenge." Thus, each party, understanding itself to be in the moral right, cannot come to any mutual common ground of understanding the crimes that are cyclically being perpetrated. As an example of this cycle of revenge, R. Scott Appleby tells of the so-called Shankhill Murders in October 1993. In this case, the Irish Republican Army was continuing a five-year cycle of violence by planting a bomb in a Protestant-owned fish shop, killing the IRA bomber and nine innocents, including four women and two girls. The author described the scene as the funeral procession for the bomber passed by some Protestant women waiting for the funeral of one of the girls. "One of the Protestants shouted, ‘You’re all yellow pigs, all of you.’…One [of the republicans] shouted ‘We got nine of yours – we can’t kill enough of you bastards.’ During the next week loyalist gunmen went on a retaliatory rampage, killing six people…"

In addition to the cycle of violence, we see in that verbal (and violent) exchange, one tribe dehumanizing the other. If one group is able to justify to itself that the other is incapable of understanding morality and justice, then the other group must be something less than human, for moral understanding is supposedly a defining characteristic of human consciousness. Consequently, "just" revenge is constituted by the crimes of a tribe in response to the unjust revenge of a dehumanized group with no moral understanding.

The human condition seems to become even more grave when examined in light of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s understanding of forgiveness. This martyred theologian described the innocent’s forgiveness of the perpetrator as an exacerbation of the suffering already incurred by the victim, for the forgiveness of a perpetrator is rarely (if ever) accompanied by the appropriate restitutive justice for the crime. The irreversibility of the deed and its consequences make it so that nothing can be done to alleviate the losses already incurred by the victim. Forgiveness would only bring with it another form of torture. This connection between forgiveness and justice is a difficult one to reconcile in most conflict situations, and it is typical that justice is not doled out in the most adequate way possible. Volf would argue that it is this reality which requires us, as Christians, to have faith in a God that will exact justice in loving perfection.

Theological Analysis

Up to this point, we have discussed the conflict in Northern Ireland from a socio-historical standpoint, utilizing Volf’s categories for human experience such as tribalism, identity, and otherness and corresponding them with specific examples. In disturbing ways, we have seen that Christianity is inextricably imbedded in the issues of Northern Ireland and that the tribal identities are deeply tied to Protestant or Catholic roots.

This connection between the religious and the political admittedly complicates the issues in Northern Ireland. However, I am arguing that at the same time, religion may also be the life preserver for a grassroots peace effort. Catholicism and Protestantism may have been part of the cause of the problem, but if the factions can be encouraged to see the common theological ground upon which they both stand, then ecumenical dialogue may be a possibility. That common ground, in part, is (divine and human) forgiveness. We will continue on using Volf’s analysis of reconciliation in theological terms, specifically, in terms of exclusion and embrace. This will reveal how forgiveness, as an element of embrace, can help heal the wounds of human suffering and estrangement. Even more specifically, we will see how Corrymeela and communities like it, make forgiveness a possibility for the suffering people of Northern Ireland.

Volf’s understanding of forgiveness has biblically based Christian origins, particularly as viewed through the lens of Jesus’ life in the New Testament. It is Jesus’ claims about and his life of forgiveness that ground the substance of Volf’s theology of exclusion and embrace in biblical terms and Christian understanding. We will examine several aspects of Volf’s thesis including the reality of exclusion and the metaphor of embrace, the theology of the cross, the theology of the Trinitarian God, and the role of forgiveness in the act of embrace.

To begin, we have already examined some of the uncomfortable realities that are present in the conflicted situation in Northern Ireland. Sectarianism is an unfortunate historical and social reality for its people. This tribalism goes to great extremes to uphold the barriers that divide Catholics from Protestants. It is this barrier or estrangement that Volf would call "exclusion." The author maintains that there are two cases which create the conditions for exclusion: (1) The bonds of societal connectedness are broken, interdependence is destroyed, and the other becomes an enemy, either pushed away or eliminated. (2) Absence of recognition that the other actually belongs at all to the pattern of societal interdependence. "The other then emerges as an inferior being who must either be assimilated by being made like the self or be subjugated to the self."

Volf clarifies that there is a distinction between "differentiation" and exclusion. Differentiation is a positive element in the forming of identity; it is the way that the self builds an identity of its own, an identity that is unique but not necessarily exclusionary of the other. Volf goes on further to say that there must be an understanding of the two notions as distinct; while differentiation is a positive good, exclusion is, indeed, evil. It is evil precisely because of its aforementioned outcomes. To reiterate, in exclusion the other becomes an enemy to be pushed away, destroyed, assimilated, or subjugated. To be able to identify exclusion and differentiation as separate and having different values and ends is, in Volf’s terms, to be able to make a judgment about them. We will shortly see how Corrymeela is one entity that can make such judgments about exclusion.

A few of the many manifestations of exclusion, as they appear in Northern Ireland, were identified in the examples in the socio-historical discussion. It is out of the context of such an ingrained form of exclusion that Volf develops his metaphor of embrace. The author defines embrace as "full reconciliation." Such reconciliation is possible, according to the author, only after truth and justice have been realized. It is helpful to think of embrace (i.e. reconciliation) as the goal in a process which includes many experiences, including forgiveness, truth, justice, peace, freedom, healing memories, and most importantly, the will to embrace the other.

It becomes apparent that forgiveness is only one component (albeit an important one) in the act of reconciliation. This component is embedded in Volf’s theology of Jesus’ death on the cross and his theology of the Trinitarian God. The author states three interrelated themes that help develop his metaphor of embrace and describe the interrelatedness of the cross and the Trinitarian God: "(1) the mutuality of self-giving love in the Trinity (the doctrine of God), (2) the outstretched arms of Christ on the cross for the ‘godless’ (the doctrine of Christ), (3) the open arms of the ‘father’ receiving the ‘prodigal’ (the doctrine of salvation). Volf draws heavily from Moltmann’s theology, as illustrated in The Crucified God, in developing his own idea of God’s solidarity with the victims of violence. However, Volf further expands on it by elaborating on the idea that Christ’s death on the cross was a divine self-donation and a reception of the other (i.e. humanity or, in fact, the enemy). The author asserts that we, as Christians, must try to emulate this self-donation through solidarity with those who are suffering while embodying the divine act of receiving each other in our humanity, reaching through the walls of our enmity.

Volf’s theology and relationality of the Trinitarian God is beautifully described in context of his understanding of Christ’s death on the cross. He writes,

When God sets out to embrace the enemy, the result is the cross. On the cross the dancing circle of self-giving and mutually indwelling divine persons opens up for the enemy; in the agony of the passion the movement stops for a brief moment and a fissure appears so that sinful humanity can join in (see John 17:21). We, the others – we, the enemies – are embraced by the divine persons who love us with the same love with which they love each other and therefore make space for us within their own eternal embrace.

And this embrace is made possible through Christ’s prayer for forgiveness as uttered from the cross, "Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do." (Luke 23:34)

According to the author, "[f]orgiveness is the boundary between exclusion and embrace." Forgiveness is impossible when the desire to exclude causes one tribe to continue dehumanizing the other and when that tribe does not identify itself as one proponent of evil. However, when accomplished, forgiveness makes it possible to break down the divisions and create an open space for welcoming the other. In addition, forgiveness is what removes the power from the problem of irreversibility. True, the deed and its consequences have not been erased, however, the control that they once had over the victim is no longer there. In The Ministry of Reconciliation, Robert Schreiter describes it this way, "That a victim can forgive is a sign that the victim has arrived at a place where one is freed of the deed’s capacity to dominate and direct one’s life… The decision to forgive is the ritual act that proclaims the freedom of the survivor to have a different future." This freedom gained in forgiving may lead to the willingness to embrace the other.

From the Christian standpoint, the decision to forgive is very much in the hands of the victim. As we saw in the example of the woman whose son was killed by a British soldier, forgiveness was not possible for her at that time. But as Volf so eloquently described, the forgiveness and love of God as seen through Christ on the cross makes forgiveness at least possible for humanity. Many years after World War II, after giving a speech on forgiveness, Corrie Ten Boom, a Dutch survivor of the Nazi Holocaust, actually met the SS soldier who killed her sister in a gas chamber. The man approached her with an outstretched hand in thankfulness, because in her talk, Corrie had described God’s forgiveness for all sinners. She recognized the man and through her seething anger for him, Corrie Ten Boom prayed vehemently that she would be able to forgive him.

"Jesus, I cannot forgive him. Give me your forgiveness. As I took his hand a most incredible thing happened. From my shoulder along my arm and through my hand a current seemed to pass from me to him, while into my heart sprang a love for this stranger that almost overwhelmed me. And so I discovered that it is not on our forgiveness any more than on our goodness that the world’s healing hinges but on His. When He tells us to love our enemies, He gives, along with the command, the love itself."

Theology of Embrace in Practice: catholicity, Corrymeela, and Forgiveness

~ One answer to the human condition? ~

After introducing the theological origins, definition and freedom of forgiveness, it is important to understand how it can be realized in the context of suffering. We have seen the deep suffering of humanity as it arises out of the evils of exclusion. Throughout Irish history, the Church has been used as an instrument of politics and sectarianism and therefore, is an accomplice to this evil. Rather than questioning the social status quo, this instrumentalization has only served to reinforce deeply ingrained societal structures and exacerbate unhealthy social divisions. Out of these divisions, exclusion arises, and Volf argues that when this is the case, the Pauline notion of the "new creation" is crushed under the weight of cultural idolatry. According to the author, the Church in fact should be a proponent of the Christian life in the Spirit that would allow us distance from culture, thereby creating a space in which to welcome the other.

This entity that welcomes the other, is what Volf terms the "catholic personality." This is a person or community whose identity is not isolated from the other, rather the identity is willingly opened to the other and informed by it. I am suggesting that this "catholic personality" is realized in the Corrymeela community. Here is just one example of how all are welcomed and accepted at Corrymeela and a new identity is created, an identity so different from that of the culture or the Church. A woman whose son was killed in the Troubles described her story like this; "I never felt at Mass what I felt at those prayers together in Corrymeela. Protestants and Catholics we were, all together, and the Protestants knew ‘twas theirs that killed my son and they prayed special for me – and it worked! I’ll never be happy again, see. But I’m not angry no more." That her church was so enmeshed in the dominant, exclusivistic culture, in part prevented the woman from experiencing the Spirit and becoming the new creation that St. Paul wrote about. Corrymeela reversed culturally accepted divisions and allowed the woman the freedom to see past the anger that had trapped her for so long.

Because Corrymeela’s identity is informed by the many identities that Christianity and Northern Ireland have to offer, it has the capability of seeing differentiation in identity and appreciating it. On the other side of the coin, Corrymeela has the clarity of vision to be able to judge what counts as exclusion (i.e. evil) in society. As we saw in their mission statement, the community is breaking down the walls that divide: "prejudices are uncovered, misunderstandings corrected, and fear is replaced by trust." Many who have never prayed with people of another faith are encouraged to do so at Corrymeela.

Corrymeela is not just a community that welcomes all and calls exclusion by its name; it is a community built to foster forgiveness. Volf declares that it is not enough to orient ourselves toward a loving and forgiving God, but we must place ourselves in a community of forgiveness in order to be most capable of such a deed. Ray Davey tells of a woman named Mary at Corrymeela whose husband had been killed by a gunman in West Belfast. Mary began talking to a man who was a reformed terrorist and told him about the death of her husband. After she told him the details of the shooting, the man said, "Thank God. It wasn’t me." She replied, "If only it had been you, I could have forgiven you." Corrymeela not only created the environment where a widow and a terrorist could sit together, but it also was a place where the two could trust each other enough to share their stories and try to forgive.

Through Mary, we can see the deep human desire to forgive. As Volf described, the ability to forgive allows for the possibility of embrace. After forgiveness, we may embrace the other, embrace our own story, and possibly even embrace our own suffering. Christ taught us to forgive, God gives us the power to do so, and communities like Corrymeela make an atmosphere where it is possible. The Trinitarian God allows us, as Christians, to experience the relationality of the divine love and share it with humanity. As a catholic community with an ecumenical orientation, Corrymeela challenges the cultural norm of tribalism, the cycle of violence, and the ingrained barriers of history, calling the people of Northern Ireland to rethink their ideas about their own identity and the identities of the other. Corrymeela judges the evils of exclusion and demonstrates the Christlike ability to struggle with those in suffering and to show them a different way than the way that culture and Church have provided in Northern Ireland.

Bibliography

Appleby, R. Scott, The Ambivalence of the Sacred: Religion, Violence, and Reconciliation. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000.

Boom, C.T., The Hiding Place. Old Tappan, NJ: Revell Books, 1971.

Davey, Ray, A Channel of Peace: The Story of the Corrymeela Community. London: Marshall Pickering, 1993.

Dillon, Martin, God and the Gun: The Church and Irish Terrorism. New York: Routledge, 1990.

Jacques, Genevičve, Beyond Impunity: An Ecumenical Approach to Truth, Justice and Reconciliation. Geneva: WCC Publications, 2000.

Kinahan, Timothy, A More Excellent Way: A Vision for Northern Ireland. Belfast: The Corrymeela Press, 1998.

Liechty, Joseph, Roots of Sectarianism in Ireland. Belfast: Joseph Liechty, 1993.

Minow, Martha, Between Vengeance and Forgiveness: Facing History After Genocide and Mass Violence. Boston: Beacon Press, 1998.

Morrow, John, Journey of Hope: Sources of the Corrymeela Vision. Belfast: The Corrymeela Press, 1995.

Muller-Fahrenholz, Geiko, The Art of Forgiveness: Theological Reflections on Healing and Reconciliation. Geneva: WCC Publications, 1997.

Schreiter, Robert J., C.PP.S, The Ministry of Reconciliation: Spirituality and Strategies. New York: Orbis Books, 1998.

Volf, Miroslav, Exclusion and Embrace: A Theological Exploration of Identity, Otherness, and Reconciliation. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1996.

Wink, Walter, Healing a Nation’s Wounds: Reconciliation on the Road to Democracy. Uppsala, Sweden: Life & Peace Institute, 1997.