Six years ago, when I was 13 (the autumn of 1900), we joined Father in New York. Our arrival was a bit forlorn, although Father did put us, bundles and all, into a large horse-drawn vehicle which took us to Czech friends - who somehow managed to put us up temporarily until we found a twenty dollar a month apartment near the East River. [522 East 82nd Street] Our neighborhood is anything but fashionable. The apartments are called railroad flats: the rooms ranged one behind the other, like a train of box cars, the dark inside rooms ventilated only by an airshaft.

Our flat has one advantage. Being on the ground floor, it has a basement kitchen opening onto a back yard, which I euphemistically call a garden. Our living quarters are cramped. We sleep two in a room except Mila, who sleeps on a couch in the dining room. All the St. Paul furniture had been sold with the little cottage. We built much of our new furnishings ourselves. We still have a straw-filled corner seat which I insisted upon installing, built of planks of wood anchored to the wall. We aren’t poor, but I do sometimes envy my school fellows their more attractive homes.

I had finished grade school in St. Paul but could not enter high school until I was fourteen. For a year I went to the East 68th Street Grammar School, repeating my eighth grade work. It was an easy, pleasant year. I particularly enjoyed my teacher, Miss Perley. One hour a week we studied drawing. Papa had given us a few drawing lessons, so in my first still-life class I had achieved a fairly good representation of a bowl of fruit. As Miss Perley passed down the aisle, she picked up my drawing and exclaimed over it enthusiastically. I was embarrassed, though flattered, too. When I was graduated I toyed with the idea of going to the Art Students' League instead of to high school. I even sent for a catalog, but when I learned that there would be a tuition fee and, moreover, that there would be a class in which I would have to draw from the nude, I renounced that idea of a career in art with alacrity! We are an old-fashioned family.

Almost immediately after my arrival in New York, I began to take singing lessons. It was a very modest beginning; I had only one lesson a week with a man who had once been a tenor at the opera house in Prague. He was now musical director of the Czech Sokol singing society, which gave an amateur performance once a year. He supplemented his income teaching singing - and he must have needed to, for my lessons cost only seventyfive cents!

That year the club decided to do Balfe's The Bohemian Girl.

After I'd been studying with him a few weeks, he invited me to be the prima donna of the production.[Photo] The music was well within my range; the rehearsals were fun. The older members of the music club made a great fuss over the long-legged newcomer from the west, and as a consequence of all this activity, the loneliness which had engulfed the rest of the family, left me untouched.

When my family first came to New York from Minnesota, we knew almost no one. The bleak, unfriendly atmosphere of a large city is hard to face, as any newcomer who has experienced it knows. So it was to the Sokolovna that we had quite naturally gravitated. Within its friendly walls we soon made friends.

Mother, however, was never able to adjust herself to living in New York. She was essentially a small-town person; she hated the pavements, the crowds, the feeling that no one in a big city cared what happened to anyone else. But she had little time for brooding with a family of five children to feed and the house-work to be done. She did every sort of household chore. If a ceiling needed to be washed, she washed it. If a new wallpaper could be afforded, she put it up. She scrubbed, sewed, cooked. I can see her now, sitting serenely in the back yard, after doing a day's washing, freshly bathed and dainty in one of her simple muslin dresses, presently coming in to prepare and preside over the dinner which she had cooked for her hungry brood.

But I? In New York, the things I had always dreamed of became realities. There were theatres to go to, even though one did have to walk to and from school to save the carfares with which to buy admission to the topmost galleries. Moreover, I was confident that thrilling things would soon begin to happen to me; I could bide my time. I kept a scrapbook of theatrical data and swapped clippings with a friendly little Jewish boy who lived in the flat above ours.

The Sokol's first performance of Bohemian Girl was a huge success. It was repeated three times and made a nice bit of money for the society. After the final performance I was presented with a handsomely inscribed gold watch.

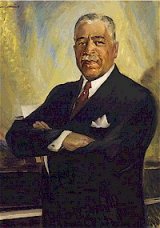

The praise I received was heady wine for a school girl. One of my admirers was a most distinguished and kindly Negro singer, Harry T. Burleigh [more, more]. He was soloist at St. George's Church and had written some beautiful songs. He said, "You must go further, my child, you have talent."

Actually, there was already an actress in our family, a cousin, Adelaide Nowak. She was very beautiful and had a lovely speaking voice. At this time she was a member of Richard Mansfield's company. Her stories of the temperamental star and of her long tours with him fascinated me; her repeated disappointments and setbacks merely seemed dramatic and well worth enduring.

My year of marking time at the grammar school over, I was sent to Wadleigh High School on 144th Street. Mother wanted me to follow in the footsteps of my father and my sister, Rose, by becoming a schoolteacher. A schoolteacher's job was safe and the pay secure. I did not argue. Nevertheless, I knew I was not going to be a schoolteacher. Always an erratic student, I applied myself only to those subjects which interested me. Languages, history, English literature I loved; mathematics I loathed. After a fairly good average in my freshman year, my marks in algebra dropped woefully.

But the English classes rehabilitated my scholastic standing. The entire school was given an examination paper on Shakespeare's Julius Caesar. This gave me a chance to shine. Mansfield had just played it at the New Amsterdam Theatre, with my cousin as his leading lady. Since Adelaide was playing Calpurnia, I had studied every line and footnote of the play before I went to see it, lest I should lose one ounce of its value. So when I turned in my paper on the play, I knew it was good. When it was returned to me, my startled eyes saw the disappointing mark: 98; only 98! How could that be? I looked up the alleged error. The teacher had made a mistake. With blood in my eye I marched up to the examining teacher. To my delight she admitted her mistake, and thanks to Mr. Mansfield and Adelaide, my mark was now 100.

First year French was another class in which I stood fairly high. Languages fascinated me. Our teacher, Mlle. Sesso, an Austrian, was stern and terrifying in her demands for perfection, but in later years I blessed her for it. My second-year French teacher I adored. She had the dark-eyed charm of a true Parisienne; yet it is Mlle. Sesso whose name I remember and whose grounding in French verbs has served me well many times since.

But my high grades in French and English were insufficient to maintain a very high student rating. I began to hate school. My brief experience as a prima donna at the Sokolovna had spoiled me. What I wanted more than anything else was to become a singer, and Wadleigh High School hardly seemed the place to fulfill that ambition.

As soon as we could manage it my sisters and I bought standee's tickets for Lohengrin. [Photos, but not necessarily the singers that I saw.]

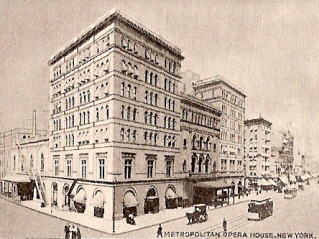

I was enchanted with the packed opera house, and we were there early enough to find space at dead center behind the rail, on which we could lean and occasionally rest our feet. As the flowing music of that first act swelled to its climax my emotions swelled too -- indeed, Mila later told me that my tears were not merely running down my cheeks but seemed to pop straight out in front of me. Undoubtedly they wet the collar of the gentleman sitting in the last row! It was a lovely introduction to the opera house where, in a few years, I was to spend so much time.

One day I saw an announcement in the daily paper that Heinrich Conried, the new impresario at the Metropolitan Opera House, was going to establish a school where potential recruits to the company would be given scholarships. Until then, it had been considered absolutely necessary to go abroad for study and training. He wished to remedy this.

The whole thing seemed miraculous: I knew I should, I must be accepted. The absurdity of my pretensions never entered my mind; some inner voice had always assured me that I must keep reaching for the stars. I took the newspaper clipping to Father and begged him to write to Mr. Conried for an appointment. He did, in his beautiful German, and the appointment was made.

On the appointed day I found myself at the opera house in a room filled with waiting aspirants: church soloists, concert singers or very advanced students. The fact that I was none of these did not faze me. One after another they sang: "Caro nome" in high, bright coloratura; "Elsa's Dream" in smooth-flowing phrases; "Mon coeur s'ouvre a ta voix," which seemed the contraltos' favorite show-piece (as was "Prize Song" for the tenors). I rose, handed the accompanist my roll of sheet music, and sang lustily "I dreamt I dwelt in marble halls" -- the only time, I suspect, that it has ever been sung for a Met audition!

Presently Mr. Conried called Father into his office. What exchange of polite German took place I never learned, but the upshot was that I was awarded a scholarship; I was to be the only teenager in the school. I cannot recall feeling any considerable surprise. Joy, yes, joy at the confirmation of what I had expected. I was to stay in the opera school for two years; after that they would see.

Father was proud and delighted. We rushed home to tell the family. Mother had misgivings, but I was too excited to listen to them. I do not remember taking any formal leave of high school. All I recall is that I found myself quite suddenly in the midst of a magical world of music -- a world peopled by brilliantly gifted men and women with fascinating personalities, a world which might well have excited a far more phlegmatic nature than mine.

Now began two exciting years. No more trudging fifty or sixty blocks to Wadleigh High School for classes in physics and geometry. Instead I flew on winged feet up elevated stairways, down again into bustling Broadway crowds; then, marvel of marvels, I walked unchallenged through the 39th Street door of the great Opera House, through which were passing the greatest singers in the world. [Exterior Photo, Interior Photo]

There were about twenty students in the opera school. We were given lessons in singing and in languages and did simple exercises with a ballet master. An important part of the work was attendance at as many rehearsals and performances as possible. Three boxes were reserved for us at the rear of the second tier. This privilege was primarily intended for the advanced students who might be understudying the minor roles, but, greedily, I became a nightly fixture.

The two years were filled with feverish activity, uncontrolled by any vestige of common sense. My voice was a rambling mezzosoprano, of very wide range but with a bad break as it went into the head register. I was told that the voice must be brought into focus. A strict vocal diet of scales, solfeggio and simple German Lieder was prescribed. As my singing teacher, Frau Jaeger, spoke no English, I had a daily lesson in German with my father. These unpretentious assignments, in contrast to the vocal pyrotechnics of my more mature fellow-students, irked me considerably. No one in my family knew the proper routine of rest and care that a young singer should observe, and I doubt that I would have listened, had anyone tried to restrain me. My morning lessons over, I would slip in to listen to whatever rehearsal was gomg on.

On one occasion my determination to miss nothing at the opera house inspired me to devise a most ingenious plan. There was to be a benefit matinee one afternoon for the retired actress, Mme. Modjeska. It had been arranged by her Polish compatriot, Paderewski. All lessons were to stop at twelve so that the house staff might take over. The program was to be brilliant, full of names, and I was frantically determined to attend the performance. Tickets were $10.00, and even standing room was $3.00. All "courtesy" was suspended, and consequently getting myself through any proper entrance was out of the question. Yet, be there I must!

When lessons ended at noon, I armed myself with a book and disappeared into the ladies' room on the second floor, locking myself into the farthest compartment. There I perched with my feet tucked under me tailor-fashion, lest they be seen by some passing eye. I sat and read for about two hours. When I saw enough feet moving about beyond the door to make it fairly certain I would not be noticed, I made a casual exit, walked downstairs, and found myself a place behind the orchestra rail, where I stood all afternoon.

After taking all that trouble, I remember clearly only one person on that program -- a willowy woman in a black velvet sheath gown embroidered in gold fleurs-de-lis, Mrs. Patrick Campbell. A cloud of black hair framed a fascinating pair of great dark eyes, and her voice was unforgettable. She read a poem, but all I remember is the beauty of her voice and her graceful movements.

In retrospect the whole circumstance of my being part of that opera house picture seems a little fantastic: a high school girl suddenly in daily contact with a galaxy of the world's most famous singers: Caruso, Scotti, Gadski, Ternina, Eames, Fremstad, Plancon, Nordica, Calve, and Sembrich, many of them the last representatives of a golden age of singing. I not only saw the great ones but heard them at rehearsals. I saw Milka Ternina, so plain in her ugly tailored clothes but noble in her artistry. I saw Fremstad blossom into the full flower of her genius, her molten mezzo extending itself note by note through the sheer exercise of her inflexible will to work and to grow, until the stubborn high notes finally became as mellow and lambent as her middle range. Then she achieved an Isolde of such physical and vocal beauty, of such poignant dramatic verity, that I would have been content never to hear anybody else in the role.

Most of my fellow-students were given small parts from time to time, such as the priestess in Aida or the bird-voice in Siegfried. The artists in the company were gracious to these neophytes. All eyes and ears, I saw the older girls starting flirtations with some of the singers: Caruso, Scotti and Saleza. So when a very tall, dark young coach looked interestedly at me, I flirted a little too, rather naively. Kurt Schindler and I held hands all through one Tristan matinee. But my little flirtation came to nothing. Like Parsifal, I walked immune in that sex-saturated atmosphere; my mind was in the cloud-world of music.

Excitement became my daily bread. The most publicized event of the season was the first production of Parsifal outside Bayreuth. uBiihnen-weih-Fest-Spiel" (a consecrated festival stage-play) was the laborious designation on the title page of the score. Richard Wagner had decreed that the opera was to be performed only in Bayreuth. This wish had been scrupulously observed as long as copyright laws made it possible to control the use of the score. This restriction was lifted when the copyright expired, and now Mr. Conried was free to do it if he pleased. He did please, for he was a shrewd and ruthless business man, quite aware of the publicity value of so exciting an undertaking. The management took full advantage of the violent opposition voiced by the Wagner family. Their accusations of desecration, heresy, violation of the Meister's express wishes made the international headlines and helped stimulate public interest to an almost hysterical pitch.

My first real student assignment was to be one of the Flower Maidens in this production. My voice was not sufficiently mature for me to do any of the solo phrases, and much as I enjoyed singing the charming second act music, just being one among so many didn't satisfy me.

But there was one part with which I knew I could do something -- the Bearer of the Grail. It involved no singing, but it would permit me to emerge from the ensemble. Because of its place in the action, I knew it could be given a value out of proportion to its seeming unimportance.

I learned that this role had already been assigned to one of the salaried members of the chorus. Undaunted, I broached the subject to the famous Munich director, Anton Fuchs, who had been brought over especially to stage this great musical event. "Please, Herr Direktor, could I not be allowed the privilege of carrying the sacred vessel in the first and last acts?" My voice was as persuasive as I could make it. Evidently touched by my eagerness, he granted my request. So, in addition to being one of the Flower Maidens, I was to have my moment of solitary glory.

As the Knights of the Grail solemnly march in for the sacrament of the unveiling of the Grail, the young Grail Bearer leads the procession, carrying his sacred burden. Reverently he places it before the suffering Amfortas and steps down. When the insistent cry "Enthiillet ... Enthiillet den Grall" (Uncover the Grail!) reaches its climax, the boy, with infinite reverence, mounts the steps, lifts the chalice out of its covered case, places it before the suffering King, and sinks on his knees in worship. Bathed in the light pouring from the sacred vessel, he is immersed in its sanctity.

I took my responsibility very seriously. On the day of the performance I fasted and kept very much to myself lest my mood be disturbed. This devotion to a beloved task had a telling effect. On my arrival at school the morning after my first performance I found my fellow students buzzing with excitement over a notice in the morning paper which I had not yet seen. The distinguished music critic of the New York Tribune, Henry Edward Krehbiel, after commenting on the Kundry and Parsifal interpretations, had written:

“And while pointing out the beauty of the work of the principals, it it is a pleasant privilege to lay a wreath at the feet of the little lady who carried the Grail with such reverent and touching consecration to her sacred duties.”

The whole adventure was a joyous one; I was fully conscious of my privilege in becoming a part of that great pattern of musical and dramatic expression, of having seen and felt the music grow from its first rehearsal until it achieved the sweep of religious ecstasy that marked its eventual performance. To live within such music, to give one's self to it, in service, however humble, makes it peculiarly one's own.

As Flower Maidens, we wore lovely flowing costumes especially designed for the production. Mine was that of an iris, and the purple flowers and lavender draperies were very becoming to my fair coloring. [Picture, Krehbiel on Parsifal] However, it was only as the Grail Bearer that I actually emerged from my student anonymity.

There were several Kundrys during the season. In my opinion Fremstad's was the finest. Her superb acting talents, the opulent sensuous beauty of her voice and figure made her seduction scene in the second act something never to be forgotten. This was a siren in whose powers of enchantment one could believe. The tragic humility of her "Dienen! Dienen!" in the last act brought tears to my eyes. [Fremstad information]

There was one prima donna whose graciousness was like sunshine. While Fremstad was my favorite artist in the company, Nordica was my favorite person. She sang only a few times and had passed her vocal zenith, but there was still an irresistible radiance about her.

I caught my first glimpse of her one afternoon when a few of us were leaving after a Flower Maiden rehearsal. As we passed along the upper corridor behind the grand tier of boxes, we heard wonderful sounds from the 39th Street lobby below. Peering down through the small windows overlooking the lobby, we saw a short woman in shirtwaist and skirt, who somehow seemed tall because of her regal carriage. Nordica, just arrived from Europe, was rehearsing the garden scene with Maestro Alfred Hertz. As she raised her head she saw our bewitched faces framed in the little windows. Without losing a beat, she beckoned to us, pointing to the chairs that lined the lobby wall. We scampered down quietly and sat in a solemnly attentive row. As she finished the brilliant second-act climax she gave us a smile full of fun and said, "Now, children, you know just how it's done."

My accolade came during a pause at a later rehearsal on the stage. As the Grail Bearer, I was kneeling beside her, near the altar, in the final scene. She put her hand on my shoulder and said sweetly, "You do this very nicely indeed, my dear."

At one of the Sunday night concerts which they used to give at the Opera House, she sang the "Inflammatus" from Rossini's Stabat Mater. As she reached the end, her famous high C rang out like a celestial trumpet call. It was a sound which no one who heard it could ever forget. I was told that in her early days, when she was a church soloist, it had made her famous. Many artists have crossed my path since those exciting days, but the glow of Nordica's personal radiance shines out most clearly. [Nordica information]

The second year of study at the Opera House found me in that turmoil of impatience which has always been my greatest failing. My greed in wanting to assimilate all the experiences and exploit all the opportunities that the school opened up to me was bound to take its toll. Such intensity created tensions dangerous to my health and voice. Maminka, disturbed that I was spending almost all my time downtown, protested that seeing and hearing so much would make me old before my time. But her warning fell on deaf ears.

Even greater pressures were added when my former singing teacher, eager to exploit my success of the previous year in Bohemian Girl as well as my scholarship at the Opera School, invited me to sing in a madly ambitious project at the Sokolovna. It was nothing less than the role of Leonora in Il Trovatore. It was sheer madness, of course, and I should have sensed danger when my teacher counselled me to say nothing to anyone at the Opera School. "They might disapprove, though of course it can't hurt you," he said. I wanted to believe him.

We rehearsed evenings. Despite a heavy cold, I struggled through rehearsals, tearing at my poor vocal chords, pounding out the high C's. Of course, the performance was a failure. To this day I cannot listen to the music of Il Trovatore [Photos] without a sense of nausea.

My second season at the Opera School progressed, but my voice did not; at the end of the term my puzzled teachers pronounced their verdict. My scholarship was to be discontinued; my voice did not justify it. Mr. Conried's blunt frankness admitted of no argument. The back-stage doors of the Opera House were closed to me forever.

After two such exciting years, the sudden slump into inactivity made life seem unbearable. I wandered about the little railroad flat in bleak despair, confused, uncertain as to what my next step should be. I would not even consider going back to Wadleigh High School, yet I found it impossible to study anything systematically by myself. I could not relax; I was sure that somehow fate would point the way.

Again, a little paragraph in the daily newspaper became my signpost. It was an announcement of the opening of the Institute of Musical Art. [IMA founding] Among its personnel was listed a familiar name, Mme. Lillie Sang-Collins, a charming Frenchwoman, who had been my favorite among the Opera School teachers. At the Opera House she had encountered certain antagonisms and had left. In my spontaneous pleasure over her new affiliation, I wrote her a note of congratulation. Out of what tiny impulses do our opportunities flower! This one bore rich fruit.

Later I learned that on the very day my note reached her, she was lunching with a very important director of the Institute, Rudolph Schirmer [Photo], head of the famous music publishing company. He asked her whether there had been anyone in the opera school whom she would judge to have a future. She replied, "Oddly enough, I've just had a note from one of the girls, a youngster whose personality impressed me. I don't recall her voice at all, but she seemed to me to have the other qualities which go to make a career."

His interest was aroused, and I was summoned to meet Mr. Schirmer. He was distinguished, charming, and very kind. Questions were asked. The abuse of my voice and its dire results were discussed, and my foolishness was censured. But I sang one or two very simple songs well enough to convince them both that there was something worth trying to salvage. I was to be given another chance and every possible opportunity to nurse the strained vocal cords back to normal. Meanwhile, I was to study many related subjects in order to achieve a well-rounded musical education.

I was overjoyed! In this unlooked-for reprieve I suddenly found myself blessed not only with a fairy godmother but a fairy godfather as well. Rudolph Schirmer's generosity and intelligent enthusiasm had helped many an aspiring artist. His charm of manner combined with his discerning taste made his wealth and position powerful instruments for good. I am so grateful that he is making it possible for me to do all the things I love most -not only does he make available lessons of all kinds, but there are also tickets to musical events and even to an occasional stage play.

Again I plunged into study, but this time quietly, sensibly, without tension. Long hours were spent in piano practice, classes in harmony, and French lessons with the famous Yersin sisters who had coached many of the greatest artists of the French theatre. I heeded their dictum: "Before you open your mouth you must open your ears." In theory, at least, the Yersin systeme if mastered would produce a flawless French accent. "We want you to become not only a good singer," Mr. Schirmer said, "but a cultivated, interesting woman as well."

Once more I was privileged to hear the best. Already steeped in opera, I now became familiar with other forms of music. Pianists, violinists, lieder singers, symphony orchestras -- I listened to them all with expanding interest and understanding.

Grateful for this second chance and determined to justify my sponsors' faith in me, I settled into a new, disciplined routine. Gradually my tense throat muscles relaxed. I sang only the music assigned to me for study, resisting the temptation to work on more spectacular things. The end of term examination gave satisfactory proof of my progress, and it was arranged that I continue at the Institute this year.

After a summer of rest and relaxation, I was eager to get back to serious study at the Institute. Under the guidance of Lillie SangCollins, I have resumed my earnest efforts to recover from the vocal insanities of two years ago. In the meantime, Mother’s health has been gravely impaired by an attack of influenza. She has lost all interest in her household tasks, is extremely nervous, and above all, dreads being left alone. She has slowly recovered from the influenza attack, but when we do succeed in persuading her to leave her bed, she either sits inert, or follow us about from room to room like a frightened child. As the others all go to their daily jobs, she repeats, "Where are the others? When are they coming home? Why must you go downtown?" I have no idea what is going on in her distracted mind, and I hate the extremes of it all. I have told Mme. Lillie little of the situation at home other than, "Mother is not very well." Actually, I am glad to put it all out of my mind whenever I can throw myself into my study and lessons.

Father’s encroaching blindness makes it difficult for him to work; we have to depend on what my two sisters earn; Mila is occupied with her dressmaking, Rose with her teaching; Charlie has an insignificant job in an insurance office. Someone had to do the endlessly recurrent housework, and so sometimes it ends up falling on my shoulders. Unfortunately, the quality of my housekeeping is sketchy, and any meals that I prepare are simple indeed. I always make what I call "Waldorf Salad," for I like the elegant sound of the name. Recently, Charlie remarked acidly, "Waldorf Salad seems to change a lot, but it always tastes like yesterday's supper."

Source: Bohemian Girl, pp. XX -YY)