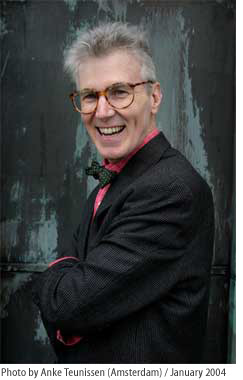

A

cinematic Ralph Nader, Noam Chomsky, and Marshall McLuhan rolled into

one, Ray Carney is a combination consumer advocate, media scourge, and

film visionary who pulls no punches in his attacks on the American filmmaking

establishment and the critics and reviewers who support it. Over the past

10 years, in a series of wide-ranging lectures and interviews, he has

tirelessly crusaded for off-Hollywood films and filmmakers.

A

cinematic Ralph Nader, Noam Chomsky, and Marshall McLuhan rolled into

one, Ray Carney is a combination consumer advocate, media scourge, and

film visionary who pulls no punches in his attacks on the American filmmaking

establishment and the critics and reviewers who support it. Over the past

10 years, in a series of wide-ranging lectures and interviews, he has

tirelessly crusaded for off-Hollywood films and filmmakers.

When he is not stumping for independent film, Carney is a prolific writer. He is the editor of the multi-volume Cambridge Film Classics series of books, and the author of more than a hundred essays and ten books of his own, including the recently published The Films of John Cassavetes (Cambridge University Press) and the new The Films of Mike Leigh (Cambridge University Press) and forthcoming Cassavetes on Cassavetes (Faber and Faber). He is currently writing a critical history of American independent filmmaking from 1953 to the present.

MovieMaker caught up with him in his office at Boston University, where he teaches courses on film and American studies. The text that follows was edited from more than eight hours of conversation on three successive afternoons.

MovieMaker (MM): Since the Academy Awards are in a couple of weeks, would you comment on the state of the art of contemporary film?

|

Ray Carney (RC): Do you realize you just used the words Academy Awards and art in the same sentence? Doesn't that feel weird? Besides being the world's most boring TV show, the Academy Awards obviously have nothing to do with art. It's a three-hour commercial for bad movies. Actors who can't act, writers who can't write, and directors who can't direct get together and give each other little trophies congratulating themselves on how wonderful they all are. Hollywood is not about art. Art isn't made by committee or by testing different versions of something to see which one the audience responds to the best.

But that's old news. Everybody knows the accent falls on the second word in show business. What's inexplicable to me is that American film schools go along with the whole thing. They actually show schlock like Fatal Attraction, Alien, Thelma and Louise, and Silence of the Lambs in film courses and invite the directors to speak to their students! I may be out of touch, but I was under the impression that the university curriculum was one thing that was not supposed to be up for sale to the highest bidder.

MM: Are you saying these films shouldn't be screened in universities?

RC: No. Just take them out of the arts and humanities courses. Screen them in the Business School. Study how they were financed. Discuss how the casting, the writing, and the ad campaigns were coordinated. Analyze them as wildly successful marketing coups–since that's what they are. Snake oil for the brain. And while we're at it, let's get the library to re-catalogue all those books about Steven Spielberg, Oliver Stone, and Ivan Reitman, so that they are shelved where they belong–next to the books on mass-marketing and public relations. I have no problem with that.

MM: But you can't deny that Hollywood has an uncanny ability to put its finger on America's pulse and involve a viewer's emotions. Movies like Forrest Gump, JFK, Fatal Attraction, and Philadelphia obviously spoke deeply to millions of viewers. The proof is that they took in hundreds of millions at the box office.

RC: You're just making my point–illustrating how Home Shopping Club values have replaced artistic ones. We don't measure Picasso's Guernica or Paul Taylor's Esplanade by how much money they rake in their first weekend. So what if a movie is popular? The Big Mac is the most popular food in America. Norman Rockwell is the most popular painter. Does that mean the English Department should dump Shakespeare and replace him with Stephen King?

As far as emotions go, if art was just about getting our feelings worked up, an auto accident or the cry of a baby would be more important than Hamlet. It's easy to get a viewer's emotions involved. Make a movie about a victim–especially a fashionable one: someone dying of AIDS or rounded up by the Nazis. Only slightly subtler, make a movie about a victim of some obvious social injustice. Take an even easier route and rely on a suspense plot with constant threats of violence. Stir and serve. I've just described 90 percent of the movies made last year. That's not art, it's just playing games with our evolutionary past–duping our reptilian brain-stems into pseudo-fright/flight or maternal/protective responses.

Look, I'll admit that I have the same visceral responses everyone else does to Natural Born Killers, Reservoir Dogs, and Pulp Fiction. I squirm. I cringe. I could hardly watch the screen while the Bruce Willis character in Pulp Fiction went back to his apartment. Even a no-brainer like Speed can leave you breathless with its propulsiveness. But what does that prove? These films are the best roller-coaster rides (in the case of Tarantino, the best haunted houses) ever made. But if that's what you want, you might as well go to an amusement park! I remember a conversation I had with a director over dinner a few years ago. He said his goal was to grab viewers by the guts with the first shot of his movie and not let them go for two hours. I asked him where he had developed such a bizarre desire. Why would he want to grab people by their guts? Why wouldn't he prefer to touch their minds and hearts?

MM: I take it you are not a Tarantino groupie.

RC: You're talking to one critic in America who isn't ready to found a religion around him. I was willing to suspend judgment after Reservoir Dogs, but it's perfectly obvious to me by now that he's a lightweight. A flash-in-the-pan. The Tarantino cult will disband in a few years and search for another Messiah, once he predictably fails to live up to his "early promise"–just like the David Lynch cult did.

MM: Why do you feel so negatively about his work?

RC: It's only that in three films–running something like seven hours in all–he has managed not to express one interesting insight into human emotion or behavior. If it weren't for daytime television, it might constitute some sort of record. All there is in his work is the Grand Guignol campiness, the chiller-diller suspensefulness, the kicky twists and turns of plot, and reversals of expectation. It's not much to go on, if you are beyond the age of 18 (which, admittedly, most of his audience is not–at least not emotionally).

What am I saying? Simply that his scenes are boring. All he has to keep them interesting is the pop-schlock tones and effects. There is not a single conversation in Pulp Fiction that is interesting enough to stand on its own without some comic-book effect to jazz it up. Without the harem-scarem jokiness and thriller plot, even his teenage admirers would be bored out of their minds.

MM: At least you concede that it isn't just buckets of blood, as some mistakenly say. His work is funny.

RC: My problem with the humor is that it is too shallow. The great comic masters–Chaplin, Mike Leigh, Elaine May, Mark Rappaport–know that comedy is a deadly serious form. In their works, we laugh from the shock of recognition. We see ourselves in extremely complex ways. The comedy is a way of suspending a viewer within the complexity. Tarantino never uses comedy that way. It's always merely for a cheap laugh at some easy irony or obvious incongruity–usually a sudden change of mood. The comedy doesn't reveal anything interesting. That's why in Chaplin, May, Leigh, and Rappaport the comedy draws us into states of intricately multivalent sympathy with the characters, while in Tarantino, it just makes us feel superior to them. The one kind of comedy makes things more complex; the other kind, Tarantino's, makes them simpler. Tarantino's comedy is similar to Altman's in this respect. It reduces and demeans, but above all it simplifies.

MM: How can you account for the critical praise that's been heaped on him?

RC: Oh, the critics are easy to buffalo. I sometimes give my students a recipe for making a movie that New York critics will champion. First, be sure you work in a well-established genre and wedge in lots of references to other movies. Play games with narrative expectations and genre conventions at every opportunity. That always appeals to intellectual critics, who like nothing better than a movie about movies. It makes them feel important. Second, include a ton of pseudo-highbrow cultural allusions and unexplained in-jokes. Critics love it when they can feel in the know. Third, strive for the "smartest" possible tone and look: as ironic, cynical, wised-up, coy, dryly comic, and smart-alecky as you can make it. It's important to avoid real seriousness at all costs, so that no one can accuse you of being sentimental, gushy, or caring about anything. That's a mortal sin if you want to appeal to a highbrow critic. If it's all a goof, like Pulp Fiction's comic-book approach to life, no one can accuse you of being so uncool as to take yourself or your art seriously. If possible, make the story blatantly twisted, surreal, excessive, or demented in some way. Make it outrageous or kinky. If the average middlebrow viewer would be offended by it, that makes it all the more appealing to this sort of critic, since shocking the Philistine is what this conception of art is about. Finally, glaze it all with a virtuosic shooting and editing style and keep a certain degree of onrush in the plot. Keep the nonsense moving right along, so no one will stop and ask embarrassing questions about what it all means. Every other interest is abandoned to keep the plot zigging and zagging–psychological consistency, narrative plausibility, emotional meaning.

It all seems pretty adolescent and Spy Magazine-ish to me, but when you're done, you've got Pauline Kael's all-time greatest hits, and the New York and Los Angeles Critics' Circle Awards winners for the past 30 years: Bonnie and Clyde, Mickey One, Clockwork Orange, Dressed to Kill, Blow Out, The Fury, Blood Simple, Raising Arizona, Miller's Crossing, The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover, Blue Steel, Near Dark, Blue Velvet, Heathers, Reservoir Dogs, Red Rock West, Natural Born Killers, Bad Lieutenant, King of New York, The Last Seduction, Pulp Fiction. I probably left a few out.

MM: Tarantino aside, aren't you being blatantly unfair to other serious movies? They aren't merely roller-coaster rides. People think when they watch them. They make complex moral judgments. They learn things. With films like JFK, Malcolm X, and Quiz Show, they are forced to re-evaluate historical events.

RC: These movies are to thinking what sound bites are to political debate. How much real thinking do we do in the course of any of the ones you have named? Lee and Stone and Redford don't change anyone's mind about anything. They don't twist our brains into knots. On the contrary, they make things easy to understand, easier than life–or real art–ever does.

The lighting, the music, the acting, the narrative events keep a viewer in the clear about what he is supposed to know and feel in every shot. You are not actually allowed to think on your own, trusted to draw your own conclusions, for a minute. All there is is button-pushing: idea number one, number two, number three. Of course, it goes without saying that if you are told what to think, you are not really thinking at all. Thinking is an active state, not a passive one.

Maybe I'm just slow or something, but in the presence of a real work of art–a poem, a painting, a ballet–I'm never able to understand things in the Stone or Lee way. I'm uncertain exactly how to feel. I have contradictory responses. The experiences a work of art offers are not simple or easy. They're hard and challenging. You have to wrestle with something that won't come clear for a long time–that won't ever come as clear as these movies do. You have to do a lot of work.

MM: What about a really serious movie like Schindler's List? Certainly it forces people to work through difficult material.

RC: I'm afraid I can't see much difference between Spielberg's serious movie and his boy's book movies. Schindler's List depends on Spielberg's inflatable, one-size-fits-all myth about how a clever, resourceful character can outsmart a system. Is that what the meaning of the Holocaust boils down to–Indiana Schindler versus the Gestapo of Doom? That's what Spielberg's entire world-view amounts to, as far as I can tell.

Stylistically, it's the same old comic-book sense of life: Schindler's List depends on the same formulaic responses to formulaic characters and situations that Jaws did. We live in a culture of mass-production and one of the products we manufacture the best is synthetic emotions and experiences. The Hollywood studios are brilliant at mass-producing stock feelings. They have perfected the art of canning them.

MM: I'm not sure I understand what you mean. How can you call an experience or a feeling synthetic?

RC: Velveeta-experiences are everywhere. It's done all the time in the human-interest stories on the evening news or in the newspaper. Wall-to-wall fake feelings. Or look at what happened during the Gulf War. A whole nation was worked into a frenzy of pseudo-emotions. In fact, I sometimes think that Americans' obsession with live television–the Iran-Contra hearings or OJ's Bronco going down the freeway–is a reflection of how starved we are for real experiences. At OJ's trial, there is at least the possibility of some reality breaking through–of something unscripted and unplanned happening. The hope is that, if only for a second, something truly real will be visible.

MM: What does this have to do with film?

RC: Well, Oliver Stone, Spike Lee, Steven Spielberg, and most Hollywood directors are masters at plugging into the emotional fad of the moment. They whip up the same sort of instant, artificial emotions that the Super Bowl does. Schindler's List, Malcolm X, and JFK cycle the viewer through a series of predictable, clichéd, plastic feelings. But it's all just a bad simulation of real experiences and emotions. Virtual unreality. The ideas are prefabricated, the experiences are formulaic, and the emotions are superficial. Which is why it's all forgotten a few hours later.

The superficiality of the experience is in fact what many viewers love about Hollywood movies. They take you on a ride. You climb into them, turn on the Cruise Control, and sit back. Not only are events, characters, and conflicts entirely predictable (most movies are their trailers), but there is nothing really at stake for anyone–actor, director, or viewer–in any of it. It's like a roller-coaster ride in this sense too–a few pre-programmed thrills and chills and then all is well. When it is over, you leave the theater and go home untouched by any of it. Anything that has happened has taken place entirely on the surface. That's what Antonioni meant when he said Hollywood was being nowhere, talking to no one, about nothing. It all takes place on a fantasy island. It's all "as if." There's no real danger or threat in any of it.

MM: What does that mean? How can a movie really be dangerous?

RC: John Cassavetes did it with every move he made–which is why he got into trouble with the critics. His movies get under your skin. They assault and batter you. His hell isn't reserved for other people. Cassavetes puts us on screen and forces us to come to grips with what we are. It is too easy to put the blame on someone else. Husbands and A Woman Under the Influence won't let us locate the stupidity or cruelty somewhere else. They have neither heroes nor villains, but only in-between characters, because that's what we are.

Spielberg could have done it with Schindler's List if he had dared to make a movie sympathetic to the SS. You may smile, but I'm not joking. How about a movie that deeply, compassionately entered into the German point of view in order to reveal how regular people with wives and children could be drawn into committing such horrors? How about a movie that showed that, at least potentially, we are them? A film that didn't locate the bad guys in an emotional galaxy far away? Of course, Spielberg could never make that film even if he tried to, because it would require too much insight on his part. And if he did make it, it would certainly not get Academy Awards–because it would not merely cycle through Good Housekeeping approved responses. It would make viewers really have to think. And thinking, real thinking, is always dangerous. They might be forced to realize things about themselves that they would rather avoid. They just might be made to squirm a little.

MM: Why don't viewers detect the falsities you are describing?

RC: Sometimes they do. Maybe it's not a matter of knowledge. Even the most untutored viewers detect the phoniness, the formulaic packaging when a film is close enough to their lives that they can compare it with something they know. That's why Reality Bites bit the dust at the box office. The teens it was supposed to appeal to were precisely the group that most sniffed out its fraudulence. It's also why most Hollywood directors have the good sense to make characters sufficiently different from their viewers' ordinary experience that the viewer suspends disbelief. The Crying Game worked because most audiences had no experience of its gay milieu. Inform yourself by viewing Gregg Araki's Three Lonely People in the Night or All Fucked Up, and The Crying Game becomes almost as cartoonish as Fatal Attraction.

MM: Do you think people would prefer the Araki movies if they saw them?

RC: Unfortunately, no. I have no illusions that Araki will ever be as well-known as Tarantino or Stone. People prefer artistic tricks to true discoveries. Truth is messier and more complex than a gimmick. Flash is preferred to real insight because flash gives the illusion of insight without requiring the actual effort of learning anything new. It's a fact of psychic life that our ideas and emotions are organized to resist fundamental change. Real art is always going to be resisted, because its experiences will never neatly fit into pre-existing categories. It makes us work. We can't just sit back and take it in. We have to wake up and scramble.

Art doesn't give us pre-cooked, pre-digested experiences, but raw, rough, unclassifiable ones. In fact, if you can say what emotions you feel while you watch a film, you probably aren't having an emotional experience in the way I mean. Real emotions defy verbal summaries. And they leave us more confused than analytic. Thinking in a new way is more likely to bewilder than to enlighten us, at least at first. If an experience is truly original, it puts us in places we've never been before and may not want to be. To paraphrase Mick Jagger: art gives us not what we want, but what we need.

MM: Is that your definition of art?

RC: Well, art does lots of things in lots of different ways, but one of the things it can do is to point a way out of some of the traps of received forms of thinking and feeling. Every artist makes a fresh effort of awareness. He offers new forms of caring. He can point out the processed emotions and canned understandings that deceive us. He can reveal the emotional lies that ensnare us. He can help us to new and potentially revolutionary understandings of our lives.

MM:

Can you give a positive example of how a film can do that?

MM:

Can you give a positive example of how a film can do that?

RC: Sure. It's more fun to praise than to criticize, anyway. The only problem is that Hollywood has such a hammer-lock on our imaginations that the major works of film art are still largely unknown–even to most film professors.

John Cassavetes' Faces is an example of a film that simply leaves behind most of the ways other movies organize and present experience, as if Hollywood had never existed. At a stylistic level, it literally shows us life in a new way– ignoring all of those old clichés about how scenes should be shot and edited: all that stuff about using intercut shot/reverse-shot close-ups for conversations; star-system hierarchies of importance for actors; melodramatic conflicts and confrontations between the characters to generate drama; and the reliance on an action-centered plot to keep the whole thing zooming right along.

At the level of experience, Cassavetes shreds most of the myths that American life and film are organized around: the worship of personal glamour and power; the myth that outward actions and the belief that we prove ourselves by competing with each other. That's what it means for a film to reject old formulas, clichés, and myths and present new forms of understanding in their place.

MM: But Cassavetes is a depressing filmmaker. Many viewers walk out of his movies. Does something have to feel bad for it to be good?

RC: You know why people leave his movies? Because they won't simplify the experiences they offer and tell viewers what they are supposed to know and feel every second. They force us to come to grips with experiences that we have to work to understand. In short, he's not Altman. He doesn't offer easy ironies or intellectual shortcuts to knowledge. He doesn't flatter us and allow us to feel superior to his characters and events. His work is depressing only if you refuse to give up your old ways of understanding. It's frustrating only if you refuse to learn from it. His truths seem fierce, only because we resist them so fiercely. Otherwise, his work is a joyous, spiritually exultant viewing experience– because it opens the door to the discovery of new truths about ourselves.

MM: How does the assaultiveness and intensity of Faces differ from the shock value of Tarantino's work? Aren't both filmmakers using what you called "tricks" or "gimmicks" to hold our attention?

RC: It's a trick if it is there simply to stoke up the drama, to churn our emotions, to grab and hold us. It's not a trick if it's in the service of profound insight. It's not a trick if it opens up new understandings. Cassavetes is not interested in shocking, but in enlightening us. We feel the shock because we register the insight. In Tarantino, there's nothing but the shock itself.

If you want a crash course on the difference between gimmicks and revelations, watch Pulp Fiction and Elaine May's Mikey and Nicky on successive nights. May creates characters who have a superficial similarity to Tarantino's in their guttersnipe jitteriness, and scenes that similarly defeat our expectations, but she does it not to astonish us, but in the service of showing us astonishing things about ourselves. She's not playing with genre conventions. She doesn't use narrative surprises or shifts of tone to hold our interest. She doesn't use gore to scare us. She gives us a scary, wonderful, shifting conception of who we are. She imagines experience as having a mercuriality, onwardness, and open-endedness that is exhilarating and terrifying. Like Tarantino's, May's scenes can be both shocking and screamingly funny, but the difference is that in May these extremes of feeling are almost accidental side-effects of the insights her work provides. In Tarantino, the shocks and the jokes are ends in themselves. They reveal nothing. They are all there is.

Mikey and Nicky shows us what great art does. It gives us new ways of knowing. It gives us new emotions, new brains and hearts, new eyes and ears. It blows our old, tired selves away and makes us, at least for a while, newborn, in a new world. MM

End of Part 1

* * *

Part 2

MM: In the first part of the interview, you were defining what great art does. Could you continue?

Ray Carney: It changes our perceptions.

MM: You mean our attitudes and ideas?

RC: Coleridge said something very interesting about this. He said that the functions of the imagination that we normally think of when we use the word–wishes, dreams, fantasies, etc.–were in fact its secondary or subordinate functions. He said the primary function of the imagination was the way we used our senses.

Tarkovsky was the first filmmaker who showed me what that really meant. Changing our ideas or philosophy touches only a superficial aspect of our being. Stalker, Nostalghia, and The Sacrifice change how we see and hear. They alter our experience of time and space–deepening, intensifying, slowing our perceptions down. Tarkovsky gets us hearing dog frequencies. It's like a drug experience, but more interesting because it's not a momentary escape from reality but a whole way of life.

MM: All the positive artistic examples you have cited are difficult filmmakers. Must a film be stylistically unconventional to be important? Can a conventional narrative work with "normal" dramatic events be an important work of art?

RC: Sure. A filmmaker I know, Caveh Zahedi, made a simple boy-meets-girl love story, A Little Stiff, that is one of the best movies of the past 10 years. If the Academy Awards actually meant anything, it would have won Best Director, Best Picture, Best Screenplay, and Best Performance of 1992. Mike Leigh is a stunning illustration of how a filmmaker can work in absolutely conventional narrative forms (with coherent plots and believable characters, no narrative tricks or temporal dislocations, and no Steadicam showboating or shock-editing to grab the attention of the New York critics), and still open a door to a stunning new vision of life. His greatest works–Bleak Moments, Meantime, Grownups, Kiss of Death, Abigail's Party–represent complete re-imaginings of what life is about. They show us things we have never seen before. There's a whole philosophy in those films–not in the trivial form of words and theories–but as new ways of seeing and feeling. (By the way, Leigh is also an illustration of the truism that an artist is often best known for his most conventional work. Naked, Secrets and Lies, and Career Girls, the films of his that most people know, are in fact slightly less interesting than his earlier work.)

MM: Can you name other filmmakers who you think are worth watching?

RC: Sure, but I'll limit myself to American filmmakers, if that's OK. Again, though, I'm afraid that none of them is a household name.

The two most important American artists of our era, in my opinion, are Mark Rappaport and Robert Kramer. I know. I know. They haven't made it to the mall yet.

MM: How many films have they made?

RC: Many. Over many years. More than Oliver Stone or Spike Lee. Rappaport's major titles are Casual Relations, Local Color, Scenic Route, Mozart in Love, Imposters, and Chain Letters. Kramer's major works are Ice, the four-hour epic Milestones, Doc's Kingdom, My Nazi, Route One, and Starting Point. (For the record, Ice more or less does what I said Spielberg couldn't dare to do with Schindler's List. It goes inside an urban terrorist group–you know, the kind that bombed the World Trade Center–and attempts to enter into their point of view. My Nazi does something similar.)

But it's obviously not enough to make a movie, however good it is. I tell my students making the movie is the easy part. The real work begins when you attempt to get someone to screen it and someone else to review it. The most interesting American filmmakers are almost all in the same situation Rappaport and Kramer are. They gave a party but no one came. They made their movies, but almost no one screened or reviewed them. That's why most people haven't heard of them. It is a miracle that they keep going at all. They give us priceless, precious gifts we don't want or ask for, and that most viewers won't ever even hear about.

MM: Who else are you thinking of?

RC: Well, off the top of my head: Paul Morrissey and Charles Burnett. Alison Anders, Claudia Weill, Su Friedrich, and Jane Spencer.... Rick Schmidt and Jon Jost.... Sean Penn, Gregg Araki, Michael Almereyda, and Caveh Zahedi.... Sean Penn, Vince Gallo, and Jay Rosenblatt.... From an earlier generation, Shirley Clarke, John Cassavetes, Morris Engel, Lionel Rogosin, Barbara Loden, and the early work of John Korty. These filmmakers are the real newsmakers and reporters of our time. They're actually more important than the journalists who write for our newspapers, because they report news that stays news–news about our emotions, our consciousnesses, our lives and relationships. They are our truest and deepest historians. Amid all the media-created fictions, they are writing the true history of our lives.

I felt incredibly fortunate to have been able to have been alive during such an artistically fertile and productive period in American film. But you wouldn't even know it had happened from reading the Sunday Times over the past 30 years. Even most film professors haven't seen these films.

MM: Why aren't these filmmakers better known?

RC: Don't ask me. Ask Pauline Kael and Vincent Canby! For 25 years, they determined what got covered in the two most influential publications in America, and consequently what lived to be distributed beyond New York. They truly could have been great forces for good over the years–educating viewers, raising standards, opening people's minds to alternatives to Hollywood–but they missed the boat. They trimmed their sails to the prevailing commercial winds. Maybe it sounds like I'm being too hard on them, but they have a lot to answer for. Their reviews had important consequences. They ended many promising careers, and slowed down many others. This is not speculation. I know many promising filmmakers who were ignored or bashed by them in print. Ask Rob Nilsson what happened to him when he four-walled a theater in the Village. Their words had consequences. There is a lot of blood on their hands.

MM:

Are you saying there is some kind of conspiracy not to review independent

film?

MM:

Are you saying there is some kind of conspiracy not to review independent

film?

RC: No. It's just the usual combination of laziness and inadvertence combined with basic bureaucratic expediency and economics. The major studios have teams of professional publicists working around the clock, revving up interest in their big-name releases. They flood the reviewers and their editors with phone calls, press packs, videotapes, and notices of special screenings. They fill every column inch with press releases, gossip column teasers, and advertising. They book the director and stars onto talk shows and lend them out for interviews. They fly cadres of reviewers to New York or LA and put them up in fancy hotels on all-expense-paid junkets for additional interviews. Then they block-book their movies into hundreds of theaters at once (made all the easier thanks to the de-regulation of the Reagan years). In the face of this onslaught, is it any wonder that the reviewer–or his editor or TV producer–harried and overloaded with claims on his attention, decides to review Little Women rather than A Little Stiff?

MM: Are there any heroes in this story?

RC: Yes, a flock of even more harried and overworked museum curators and specialty film programmers who have supported creative work over the years: Bruce Jenkins at the Walker, Bill Banning at the Roxy, Bo Smith at Boston's Museum of Fine Arts, Bruce Goldstein at Film Forum, John Gianvito at the Harvard Film Archive, Marie-Pierre Macia at the San Francisco Film Festival, Jonas Mekas at Anthology Film Archives–and many others. And a few staunchly independent critics who actually review the films that play at such places: Jim Hoberman, Dave Kehr, David Sterritt, and Jonathan Rosenbaum being the best of the bunch. What's strange to me is that "independent" reviewers are a special category, and so few and far between.

You can expect the publicists to have sold their souls, but I still can't get used to the critics functioning as extensions of a movie's ad campaign and not even seeing any problem with that. If you count the publicity junkets, virtually every reviewer in America is being paid by the studios.

MM: Let me switch to a larger issue. Many would argue that your position is founded on the fallacy of treating film as a high art. They would say that different critical standards apply to popular art.

RC: This special pleading for separate "levels" of art has always baffled me. It seems to me there is good, stimulating, revelatory work; bad, boring, derivative work; and lots of work that is a little bit of both. Invoking special levels of appreciation doesn't change anything in any of it.

There's no high art and low art. There's only good art and bad art. Pop art and mass culture are concepts invented by film professors to justify to their deans why they are screening junky movies in their classes. Pop art is a contradiction, just as pop science or pop mathematics would be. Art is an effort to explore, understand, and express human experience. Sometimes the understandings it arrives at are popular and you get rewarded; other times they are heretical and you get burnt at the stake; usually no one notices one way or the other and you are ignored. But whatever happens–whether your art is popular, unpopular, or neither–it doesn't change the value of what you did. It's interesting and enlightening, or it's not.

I'm not just playing with words. If there is a fallacy to be rooted out, it seems to me that it is on the other side: It is the pop-art belief that art is somehow an emanation of the zeitgeist, and that the appreciation of it is some kind of mindless, Jungian communal event. It's just not true. All valuable art is the expression of an individual vision. It isn't something in the air that magically appears when a certain number of people gather together. Similarly, the appreciation of a work of art is always the result of an individual effort of understanding. You don't just breathe it in. It takes work, knowledge, experience, effort. The understanding of art is not natural or inevitable or effortless or mindless.

A concept like mass culture does not apply to art. In fact, in the deepest sense of the word, there is no mass culture. All culture is individual culture. It is your culture and mine–somebody's not everybody's. You can't inherit it. You can't be born into it. Everyone–you, me, and Henry James–starts from zero. That's the fun and challenge of working with students. Everyone has to start at the start and go over the whole ground. There are no shortcuts. And no one can do it for you. , You can't get it out of Cliff's Notes. You have to live into it slowly and unsurely, in space and time. You have to earn your right to it.

MM: But aren't you just expressing a form of high-culture snobbery? What about ordinary people?

RC: The pop-culture, mass-culture position is the snobbish one that doesn't respect the average person. If you are engaged in anything seriously–auto-mechanics, cooking, soccer playing–you have to work at it. You have to study and master its traditions. It isn't mindless or instinctive. You get better at it the longer you do it. The plumber who came to my house last week understands the work of culture better than most professors–in his case, the culture of plumbing. He knows it takes time and work and knowledge to be a good plumber. I'm only asking that we take film as seriously as he takes plumbing.

MM: Yet there clearly are works and events that aren't created by the vision or labor of one person, and that are experienced by groups of people in a fairly mindless, relaxed way–sporting events, for example. Why can't Hollywood movies be appreciated as being more like these kinds of experiences?

RC: Well, they can. But then you are no longer talking about anything having to do with art, or anything very valuable at all for that matter. Watching the Terminator movies is a lot like watching a football game. Watching Malcolm X is a lot like reading one of those simple-minded children's biographies they assign you in middle school. Watching Top Gun is a lot like playing a video game. But what does that prove? It proves that schlock movie experiences resemble schlock non-movie experiences. The confusion arises when we try to dignify either set of experiences by giving them the fancy title of "popular art" or by calling them expressions of "mass culture" so that we can include them in a course. Why not just call them mindless, trashy vegging-out?

The advantage is not only a terminological clarity. If we called these films by the right names we wouldn't make the conceptual error of freighting them with portentous sociological or psychological meanings either. The Terminator, Forrest Gump, Top Gun, or ET are not profound expressions of our society or its beliefs. They are not tap roots into our psyches. And one obvious reason they are not, is that they do not truly emanate from ordinary people the way primitive paintings or quilts or hope chests do. These movies are planned and funded by big corporations to make money. They are conscious and deliberate corporate contrivances to take seven dollars and fifty cents out of as many pockets as possible. They are not anonymous expressions of the voice of the people. They are business deals put together to make money by a group of millionaire California producers, agents, and venture capitalists. In that sense, Spielberg's movies are far more "elitist"–less an expression of the concerns of the ordinary person–than any movie Jon Jost ever made.

This seems to be forgotten by every sociological and historical critic in our universities. All that stuff about how Thelma and Louise represents a "new feminist consciousness" or Rambo documents "suppressed male rage" is simply silly. As someone once said, you could base the science of botany on Monet's paintings, but it would be neither good science nor good art criticism. Similarly, an attempt to draw conclusions about race or gender relations from what appears in Hollywood movies makes as much sense as writing essays on paleontology based on what appears in The Flintstones.

MM: Are you saying that courses on film and mass culture shouldn't be taught in the university?

RC: Well, I started out by saying they belong in the Business School. But seriously, I'm willing to let the history and sociology departments do whatever they want with these movies (although I still think the result will be bad history and sociology and worse film criticism). What I resist is the creeping "sociologization" of the humanities–of the English Departments, film programs, philosophy programs, language programs.

MM: What do you mean?

RC:Our age is the age of the social sciences. Social science understandings have triumphed. They are the dominant forms of understanding in our culture–on television, in the newspapers, in classrooms. Virtually everything is understood sociologically, ideologically, or psychologically. That's why it's the one form of understanding I never need to teach. If I ask a group of beginning students to comment on a work, a sociological understanding is their automatic way of understanding it.

MM: What do you mean by a sociological understanding?

RC: In a sociological understanding the undergoings and efforts of individuals are forgotten. The precious uniqueness of individual consciousness is forgotten. You become your group: your gender, your race, your social and economic status. Characters in movies are rich-poor, Black-White, men-women, bosses-secretaries, etc.

It's the usual way movies are understood. In fact, the way most art works are understood nowadays. We turn them into allegories about race, class, and gender. Art is thought of as offering us social and political insights into our culture. Now, any dominant language passes for nature and not culture, so that may sound perfectly neutral and unobjectionable, but the problem is that art's ways of knowing effectively begin where sociology's ways of knowing end. It takes the art out of the art. We might as well be reading the newspaper!

Art is not only a million times more subtle than that, it is different from these ways of knowing. Sociological knowledge is a form of group-thinking, the understanding of the experience of a group, by a group. Art is the opposite. It represents the understanding of the experience of an individual by an individual. It is about unique and personal ways of experiencing.

Sociological understandings may be of use in interpreting census figures or compiling actuarial tables, but they are almost completely irrelevant to understanding the ebbs and flows of consciousness embodied in the greatest works of art. The language of the greatest art is not translatable into the language of sociology. Almost everything is lost in the translation from art-speech to sociology-speech. That's why almost all sociological criticism is doomed to be bad, and why the works sociological accounts of art can account for are the weakest works of art.

MM: Can you elaborate on what you mean by the art being a language, or is that just a metaphor?

Sure, I give lectures on the language of film and mean it very literally. I'll tell you a story. A number of years ago I actually met with a Dean of Humanities and tried to persuade him to change the university's undergraduate and graduate language requirement to allow arts to count as foreign languages. Instead of wasting two years studying German or French, skills which are then almost invariably never used again, I said that students should be allowed to take a specified series of courses in an art, so that they could learn a language they would be able to "speak" and "read" the rest of their lives. They would learn a specific dialect of art-speech–poetry-speech, dance-speech, music-speech, painting-speech, etc. That would be a skill they could continue to use and enjoy. Well, the Dean apparently thought the whole thing was some kind of elaborate deadpan joke, and never took it any further (laughing). Maybe someday when I start my University of the Arts.

MM: Does that affect your teaching in any way?

When I teach arts courses, as far as I'm concerned, that's what I'm doing and that's how I describe it to students: I'm teaching a foreign language, a language fully as intricate and subtle and complex as any verbal foreign language. Robert Frost once wrote an essay titled "Education by Poetry" in which he argued that by studying the expressive strengths and limitations of poetic language you could learn about all of life and consciousness. Well, I teach education by film.

By the way, does that make it clear why I have problems with sociological approaches to film–all of those ideological, multicultural, or gender-based understandings? They are like bad social workers, who rather than learning the language of the neighborhood, and letting it speak to them in its own distinctive way, insist that their subjects speak in their tongue. They look through the work of art–at what they consider to be the sociological facts it points to–rather than learning how to function within it, in accordance with its own ways of understanding.

MM: Does your linguistic approach affect your choice of films to teach?

RC: One of the best ways to explore and master the expressive possibilities of any language is to negotiate examples of the most brilliantly creative and revealing uses of it. If you really want to understand English, you study Shakespeare, not the newspaper. That is why, in terms of film, my students and I work through movies by the great stylistic masters: Dreyer, Tarkovsky, Leigh, Cassavetes, Rappaport, Ozu, Rossellini, and Renoir–rather than wasting our time on Hollywood hacks. And it is work, but it's fun too.

MM: Aren't you implicitly urging a form of connoisseurship or aestheticism, where students and teachers sit around admiring the virtuosity of a film's style?

RC: No, no, no. The reason the English professor has his students reading Antony and Cleopatra and I have mine looking at Ordet or The Influence of Strangers is not to stroll among the masterpieces, or to cultivate "aesthetic emotions" (whatever that means), but so that they can discover practical, important things about their lives and experiences. Negotiating the emotional challenges, intellectual defamiliarizations and expressive dislocations of a great work of art is not an exercise in idle "connoisseurship." In working their way through stylistically demanding films by Dreyer, Loden, Cassavetes, or Rappaport, my students are not tiptoeing through the tulips. They are having experiences that are equivalent to the most intense, demanding, and mind-expanding experiences they will ever have in life. They are being forced to see, hear, think, and feel in new ways. This is not dilettantish aestheticism. It is learning new forms of caring, loving, and understanding.

But again I'd emphasize that the knowledge they acquire is different from what usually counts as knowledge in our culture–specifically, it's incompatible with the simple-minded formulas of sociology and psychology. The only reason that sociology seems to be real knowledge and art seems to be flaky knowledge relates to the point I already made–that flickering, spatial, temporal, and emotional ways of knowing–art's distinctive ways of knowing–aren't acknowledged as being fully legitimate. If something doesn't translate into psychological or sociological–or scientific–platitudes, it seems "useless" or "irrelevant." The fancy term for useless, of course, is "aestheticism." Art's way of knowing are just as valuable and rigorous as science's. That's what's forgotten in the current intellectual climate.

MM: What are your goals as a teacher?

RC: Even though I reject multiculturalism's specific assumptions, I accept its stated goal: the explorations of otherness. My difference from the multiculturalists is that I define otherness not in terms of race, class, and gender, but consciousness. The greatest artists give us the amazing opportunity to see through others' eyes, to feel with their emotions, to think with their brains. That's what it means to say that, at its greatest, art offers new ways of knowing–not merely new facts, events, details–but whole new structures of knowing and feeling. Art gives us the greatest of all possible gifts–the gift of a new consciousness.

MM: It sounds almost mystical. Are you sure it can be taught?

If it can't, I should resign my job. It's what I'm paid to do. But, let me bring this back down to earth. What I am doing in a course is not fundamentally different from what a physics or economics professor does. It would be a trivial economics or physics course that merely taught students a set of new facts and formulas. The goal of the course is much more radical than that. It is to learn whole new forms of understanding. Students learn to look at the world with the eyes of an economist or a physicist. They end up by being able to see structures, connections, and events that were previously invisible to them. Well, what arts students learn is something like that in terms of human emotions and relationships. To negotiate John Milton's frames of reference, Henry James's syntax, John Cassavetes' editing, Carl Dreyer's camera movements, or Renoir's frame spaces it to learn new forms of sensitivity and awareness. Of course, when that happens deeply–when we have our minds expanded sufficiently, it is almost mythical in effect. There is a new heaven and earth. And, at least for me, as a mind-expander, it sure beats economics hands down!

MM: Can this actually be done in a course?

RC: I sometimes envy the football and basketball coaches who get to spend all day and most weekends with their charges. I have them so few hours a week, and fundamental changes obviously take more than a semester to happen. But they do happen to the students who allow them to.

Let me again insist that although a deep immersion in art may be one of the best and fastest ways these fundamental perceptual changes can take place, I'm not really talking about something entirely unrelated to nonartistic experiences. The same sort of deep learning takes place in many areas of life. Rookie NFL quarterbacks talk about the game "slowing down" after a year or two. Apprentice piano tuners talk about weeks of frustrated listening, and then suddenly being able to "hear the beats" without even trying. Wildlife trackers talk about gradually being able to "read" a trail better and better. That's what I teach–slowing down the film, hearing its beats, being able to follow the wandering tracks of consciousness without losing your way.

MM:

But how do you get someone to hear something they initially can't,

and that they may not even know is there?

MM:

But how do you get someone to hear something they initially can't,

and that they may not even know is there?

RC: Learning anything really new and different is a very mysterious process. The most important thing for the teacher is to be modest: to realize that he or she is only a kind of facilitator. Since we can't really learn anything until we are ready for it, the deepest learning can't be forced to happen. You have to be patient. Second, real learning always has to come from ourselves. No one can do it for us. So a teacher can only take students so far.

I think of myself as a Johnny Appleseed, preparing the soil and planting seeds, dousing them with a little shower or throwing a beam of light on them from time to time. I have to accept the fact that a lot of them won't sprout for a long while. And some won't ever sprout because the soil is too rocky or unfertile or poorly prepared. The growing takes place so deep under the surface that it is invisible for a long time–to the student and to the teacher. Why there are things my teachers said to me 15 years ago that are still sprouting.

One other thing. Sometimes the job of the teacher involves making things a little hard on the students, so this isn't necessarily all fun and games. A lot of times learning involves undergoing a certain amount of pain or confusion for a long while. That's an essential part of the process. A twelfth-century Zen Master once said that when his students were deep in a hole trying to clamber out, it was sometimes the job of the teacher to throw in a bramble bush, rather than to lower a ladder. Sometimes we have to tear ourselves up a little to get anywhere that matters. A teacher who makes it too easy is not doing you a favor.

MM: Any final thoughts on teaching before we end?

RC: Only that all this talk about my role as a teacher just slightly misrepresents what is actually going on in the classroom. I am really only the teaching assistant. The works themselves are the true teachers. The most intense learning is often taking place during the screening, not afterwards during the lecture or discussion. At least I know that's the way it was for me as a student. I learned far more from teachers named Shakespeare, Emerson, James, Dreyer, Wordsworth, and Cassavetes more than I ever did from anyone with a Ph.D.! The professors are always the last to know anything. The students, artists, and young actors are always way out front.

–Excerpted (in an edited and corrected version) from MovieMaker Magazine May-June 1995, p. 28-30, and 43-5; and MovieMaker Magazine Issue 14 July/August 1995, p. 18-22.

This page only contains excerpts and selected passages from Ray Carney's writing. To obtain the complete text of this piece as well as the complete texts of many pieces that are not included on the web site, click here.