The

idea for Husbands can be traced back to Cassavetes' need for cash

to pay Faces' lab bills in late 1966.

The

idea for Husbands can be traced back to Cassavetes' need for cash

to pay Faces' lab bills in late 1966.

I needed money in order to complete Faces and I couldn't afford to spend the time working at it, so I asked my agent if he had any thoughts on the matter; he told me that I had to work for my money just like everyone else. I really can credit Jack Gilardi, now a CMA agent, for giving me the ammunition to begin this craziest, most painful project that I've ever been involved in. I don't dig rejection – not even when it's practical. It's my button – push it and I go for two or three years. Which is just about the time I take to make a picture. There's an American answer to everything– it's called "Oh yeah?" and then it's followed by something like "How about this?" and then a series of cheap, ostensibly commercial ideas pop out uncontrollably, and that afternoon on the Paramount lot Husbands was born. It was told first to Gilardi and then to a Paramount producer who offered me $25,000 cold cash for it on the spot. That was everything I needed at the moment, but the perverseness had started and somehow Faces would have to struggle through without me selling crappy ideas to greedy men.

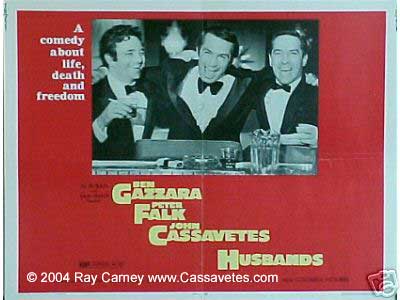

Shortly after that, Cassavetes approached two friends, Lee Marvin and Anthony Quinn, with the proposal that the three of them, in Marvin's words, "Travel around the country, stop in all those honky-tonk bars, and then [Cassavetes would] write a story based on all that, and we'd go shoot it." Quinn and Marvin turned him down (chiefly because they didn't get along with each other, as they discovered during a meeting at Cassavetes' house in which he tried to sell them on the idea). The idea resurfaced a few months later, in mid-1967, after a chance meeting with Peter Falk at a Lakers game. (Cassavetes bet heavily on many different sports events and was a courtside regular at Lakers games.)

Two people I had always wanted

to work with were Gazzara and Falk. Actors have mutual respect for each

other, and the combination of three impossible people verging on lunacy

appealed to me. I bumped into Falk at a basketball game. We said a quick

hello and he asked me if I wanted to do a picture with him. We met on

the Paramount lot again, in the commissary, and had lunch. He described

Mikey and Nicky. It sounded good but I couldn't wait to

spill my guts. It was tough communicating with Falk and when I told him

the outline of Husbands I think he was starting to change his mind

about Mikey and Nicky.

Two people I had always wanted

to work with were Gazzara and Falk. Actors have mutual respect for each

other, and the combination of three impossible people verging on lunacy

appealed to me. I bumped into Falk at a basketball game. We said a quick

hello and he asked me if I wanted to do a picture with him. We met on

the Paramount lot again, in the commissary, and had lunch. He described

Mikey and Nicky. It sounded good but I couldn't wait to

spill my guts. It was tough communicating with Falk and when I told him

the outline of Husbands I think he was starting to change his mind

about Mikey and Nicky.

That's Cassavetes' version of the story. Falk characterized the commissary meeting as being zanier and more embarrassing. He said that when he started to talk about Mikey and Nicky, Cassavetes agreed to do it so fast that Falk thought he wasn't taking it seriously. When Falk told him he wanted to tell him the plot and give him a copy of the script, Cassavetes began gesturing wildly and talking ever louder, until he was standing up and shouting at Falk in the middle of the dining room, with everyone in the commissary staring at him as if he were a lunatic. In Falk's paraphrase:

What do you think? I don't know Elaine May can write? I don't know you can act? You think you need to pitch it to me? You think I'm one of these businessmen! You think I am like you and have to have everything figured out before I begin something? That I have to have all the details in place? That I'm afraid to take a chance? That I have to play it safe? Elaine's making it; you're in it; that's all I need to know.

It was the sort of performance that outraged half of the people Cassavetes interacted with and amazed and inspired the other half. It was also Falk's first insight into the crazy man behind Husbands. The way Gazzara got involved was that Cassavetes was pulling out of Universal in his car and spotted Gazzara across the parking lot.

Two days later I was at Universal, on the lot, and I waved a fast hello at Gazzara, who had the same agent, Marty Baum, and shouted to him, "You want to do a picture with Falk and me? Call Marty." Ben's voice echoed back across the lot. His voice is so loud that I couldn't understand what he said but I knew it was positive, which in Hollywood terms means maybe.

As

Gazzara tells it, the totality of his contact with Cassavetes was

two casual encounters, neither

of which Gazzara took seriously. The first was the one Cassavetes describes

above – an indistinguishable shout in a parking lot

in March or April 1968. The second was four days later. Cassavetes

invited

Gazzara

to lunch

at Hamburger Hamlet and told him the story of Husbands. But when

Cassavetes concluded by saying that he didn't actually have any backing

for the film – no money, producer or studio interest – and

had not even written the script yet, Gazzara wrote off the encounter

as typical Hollywood

glad-handing, the sort of "we must work together someday" thing someone

said to him at least once a week at a party.

As

Gazzara tells it, the totality of his contact with Cassavetes was

two casual encounters, neither

of which Gazzara took seriously. The first was the one Cassavetes describes

above – an indistinguishable shout in a parking lot

in March or April 1968. The second was four days later. Cassavetes

invited

Gazzara

to lunch

at Hamburger Hamlet and told him the story of Husbands. But when

Cassavetes concluded by saying that he didn't actually have any backing

for the film – no money, producer or studio interest – and

had not even written the script yet, Gazzara wrote off the encounter

as typical Hollywood

glad-handing, the sort of "we must work together someday" thing someone

said to him at least once a week at a party.

The only other contact either man had with Cassavetes for months after that was invitations to preview screenings of Faces in the spring of 1968. Cassavetes was working on them, though neither of them knew it at the time. He knew that once they saw Faces, they would not be able to resist working with him. And he was right.

Meanwhile, he was simultaneously hatching a plan to get financial backing for the picture. Flash ahead a month or so after the last conversation with Gazzara. It's now mid-April 1968. Cassavetes has just arrived in Rome to begin acting in Bandits in Rome, which will be shooting for the next six weeks until the end of May. Gena Rowlands is already there when he arrives. She is scheduled to act with her husband in Machine Gun McCain, which doesn't start until the beginning of July, but has decided to take a spring vacation before the summer shoot. As a condition of her employment, she has asked for and been given a villa outside Rome to live in from March through August. Cassavetes is too busy to spend much time there, since almost every weekend when he is not acting he is flying back and forth from Rome to the United States, finishing up the editing on Faces and beginning the cycle of preview screenings intended to persuade a distributor into releasing the film.

But on one particular night the stars are aligned. Rowlands and Cassavetes are in Rome together at dinner with the producer of Machine Gun McCain – Count Ascanio Bino Cicogna, a young Italian millionaire who doesn't know very much about the movies but loves the romance of dabbling in them. Cassavetes sits next to him and subtly eases into his pitch. It is the kind of moment that he was an acknowledged master of. He was a born charmer, and as an improvising actor, exceptional at telling a story. He knew how to relate just enough of it to spark your imagination but leave you hungry to know more. When hedipped his head, looked at you through his eyebrows and dropped into the hush-hush whisper he used at times, he could make the prospect of filming the telephone book seem exciting. Cicogna was putty in his hands.

I was in Rome making a picture,

Bandits in Rome, for De Laurentiis – picking up that money for

Faces. Bino Cicogna, a new mogul on the motion picture scene [who

headed his own production company, Euro International, and would subsequently

be producing Machine Gun McCain], wanted me to do a picture for

him. We had dinner. The conversations are always the same:

I was in Rome making a picture,

Bandits in Rome, for De Laurentiis – picking up that money for

Faces. Bino Cicogna, a new mogul on the motion picture scene [who

headed his own production company, Euro International, and would subsequently

be producing Machine Gun McCain], wanted me to do a picture for

him. We had dinner. The conversations are always the same:

"What

are your plans?"

"I have two pictures I want to make – one's about Mexican migratory

workers but I'll tell you up front the price is five million."

"Who's in it?"

"Can't make it without Tony Quinn."

"Has he read it?"

"No, but he'll do it."

"What's the other picture?"

"It's called Husbands."

"Who's in that one?"

"Gazzara, Falk and me." (I knew I should have said Gazzara, Falk and

I, but I can't stand to talk like that.) I stared at the steely eyes

of

Count

Ascanio Bino Cicogna. There was a long pause. Then some unpleasant interruptions

just as I was about to close. There was a big party at the table including

my wife, Gena Rowlands, and another very interesting person, Professor

Fred Hoyle, and my very dear friends the Shaws. The place was dark and

the tables were very low so I was sitting high and I didn't care. Actually,

San Andrews is a very fine place to make deals.

"Gazzara, Falk, eh? And you're in it too? Who directs?"

"Well, it's my story and I thought I'd direct it and star in it too.

If that's OK with you."

"Let's make a two-picture deal."

"The Mexican story has a great deal of violence – it's a good

story and it has a great deal of violence." Cicogna loves the Mexican

story.

I try

to tell Cicogna that I don't think the Mexican story would ever recoup

its money.

"Can you get Tony Quinn? Who plays the girl?"

"I wrote it for Gena."

Cicogna's eyes flash across the table and case my wife. It was a fast

businessman's study and the light was right.

"Gena would be very good. When can I read it?"

"The script is in L.A."

So it's a two-picture deal for A Piece of Paradise and Husbands,

contingent upon Quinn in the first one and Gazzara and Falk in the second

one.

I spent the next few days trying

to nail Tony to read the script. He was in Rome making The Secret of

Santa Vittoria, and Sam Shaw, who introduced me to Tony, was to produce

the film, Sam being my best friend and I believe Tony's best friend at

the same time. Getting the money from Cicogna was easy – breaking through

the dinner parties at Tony Quinn's house was something else. His house

is some forty to fifty miles from Rome and I hate cars. But as soon as

the script arrived from L.A. I was on that road. Tony is still a friend

and still the only man that could play the part. But it's like being in

love with a woman who isn't in love with you – there's nothing you can

do about it. When the Mexican film blew, Cicogna never batted an eye:

I spent the next few days trying

to nail Tony to read the script. He was in Rome making The Secret of

Santa Vittoria, and Sam Shaw, who introduced me to Tony, was to produce

the film, Sam being my best friend and I believe Tony's best friend at

the same time. Getting the money from Cicogna was easy – breaking through

the dinner parties at Tony Quinn's house was something else. His house

is some forty to fifty miles from Rome and I hate cars. But as soon as

the script arrived from L.A. I was on that road. Tony is still a friend

and still the only man that could play the part. But it's like being in

love with a woman who isn't in love with you – there's nothing you can

do about it. When the Mexican film blew, Cicogna never batted an eye:

"Let's do Husbands."

"You want to do Husbands?"

Now this is amazing considering he made Quinn a handsome proposition and

that a director never looks good when he promises something and can't

deliver. Thank God I have ego and still counted on Gazzara and Falk.

Though it's impossible to know if it figured in Cassavetes' calculations, it was probably not a bad idea to have pitched Husbands to a foreigner, since the story was not that new. An American producer would have remembered Delbert Mann's 1957 The Bachelor Party or Sidney Lumet's Bye, Bye, Braverman, which was filmed six months before Cassavetes made his pitch in Rome.

A Piece of Paradise was the old script Cassavetes had written back in 1960, prior to Too Late Blues. Cassavetes had been peddling it at this point for almost ten years. He no longer had any particular passion for it; it was merely something to sell Cicogna if he could. As to its $5 million production cost, Cassavetes simply made up the amount on the spot. A few years later, in June 1974, he unsuccessfully tried to sell the same script to Sam Peckinpah.

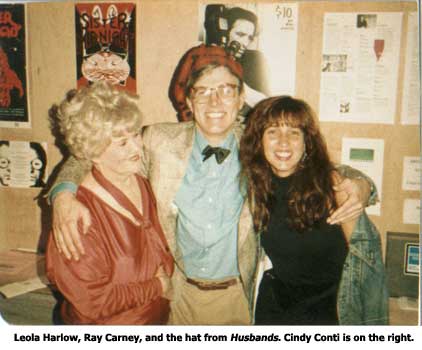

Cicogna asked to see the script of Husbands as soon as possible. What he didn't know was that it didn't exist. Cassavetes talked a good line but hadn't yet written anything. But, as he once said, "plunging in and just doing something is the best way to make it happen." He went back to his Rome villa and dictated the screenplay over the next two weekends. It uncharacteristically provided lengthy stage directions and shot indications to make the project seem more real to Cicogna. Cassavetes sent it to the financier as soon as he was done, telling him that he had had it flown in from Los Angeles. Largely on the strength of the two other stars Cassavetes assured him he had lined up, Cicogna drew up a memorandum of agreement committing financing for the project. (It's worth noting that although all of the surviving screenplay drafts are titled "The Husbands", Cassavetes' preferred title was actually Harry, Archie, and Gus because of the film's focus on friendship – though the title change was vetoed by Columbia.)

That left only two more problems to cope with. Falk and Gazzara didn't know they were going to be in the movie Cassavetes had pledged them to star in. Cassavetes would now have to produce his two co-stars. Time was running out, since it was now June 1968 and part of Cassavetes' pitch to Cicogna was that shooting would begin in New York in December. (He mistakenly counted on a quick sale and distribution of Faces and saw no reason to sit around doing nothing.) Cassavetes had Cicogna's office wire Cicogna's memo to Falk, who was in Belgrade working on Castle Keep. Falk was baffled when he received it, since he had forgotten all about the picture. But, as Cassavetes had realized when he made the pitch to Cicogna, Falk was scheduled to come to Rome in July to act in Machine Gun McCain with Cassavetes, and Cassavetes was sure he could talk him into it.

It takes Peter about a year to make up his mind about almost any point that has to do with acting – when he understands something clearly he asks you to tell him again. I know one day we will all be partners, Falk, Gazzara and me, and we've already decided and appointed Falk the decision-maker. Anyway, Peter agreed.

The final step was to get

Gazzara on board. Cassavetes' strategy of inviting him to a preview screening

of Faces paid off. Gazzara was bowled over by the film and ready

to take Cassavetes' proposal seriously. At that moment, Gazzara was in

Prague acting in The Bridge at Remagen. It was the summer of Prague

Spring, with Russian troops and tanks all around him. He says Cassavetes

called his hotel and began, "Ben, don't get killed. I got money for our

picture." Though Gazzara didn't know what "our picture" was until Cassavetes

reminded him, he was interested enough to fly to Rome to meet with Cassavetes

and Falk on weekends to discuss the script. When Russian troops took

over

most of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, Gazzara's shoot was fortuitously

moved to Rome, and the three men were finally together for a few weeks.

The final step was to get

Gazzara on board. Cassavetes' strategy of inviting him to a preview screening

of Faces paid off. Gazzara was bowled over by the film and ready

to take Cassavetes' proposal seriously. At that moment, Gazzara was in

Prague acting in The Bridge at Remagen. It was the summer of Prague

Spring, with Russian troops and tanks all around him. He says Cassavetes

called his hotel and began, "Ben, don't get killed. I got money for our

picture." Though Gazzara didn't know what "our picture" was until Cassavetes

reminded him, he was interested enough to fly to Rome to meet with Cassavetes

and Falk on weekends to discuss the script. When Russian troops took

over

most of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, Gazzara's shoot was fortuitously

moved to Rome, and the three men were finally together for a few weeks.

Thus began a series of catch-as-catch-can meetings between the three men that would extend through the rest of 1968. For the next six months, while Cassavetes was completing his acting obligations in Machine Gun McCain, arranging various festival screenings of Faces, flying between England and the United States to give interviews and attend events to promote the release of the film, and holding production planning meetings with the producers and senior members of the crew of Husbands, he spent every spare minute rewriting the screenplay – passing at least five different drafts on to Falk and Gazzara, responding to their comments and criticisms and writing the next draft. It's no wonder Cassavetes bristled at the post-release calumny that he and his co-stars had 'winged' the movie.

Before Husbands was a screenplay, I must have done about 400 pages of notes. I thought about it for several years. Then there was a screenplay. My first draft was abominable – all the pitfalls of that first-told tale – a slick farce predicated on men running away from their wives to the lure of the will. There are certain catchphrases that people are attracted to made famous by Time magazine, such as "Swinging London" – and there's always someone standing around behind you who says, "That sounds funny," but when you look into the eyes of two artists who want the best for themselves and want to be associated with something that has some meaning that's not good enough. The characters were empty. During the second half of 1968, Ben, Peter and I passed dozens of revisions of the script around everywhere we went. From Rome [where most of the interiors of Machine Gun McCain were filmed] we had been to Las Vegas, New York, San Francisco [where the exteriors for Machine Gun McCain were filmed], Los Angeles and back to New York [where Gazzara lived and Cassavetes was supervising the release of Faces]. We had followed each other around using every spare moment we could find to assess the values of three men - three New Yorkers with jobs, who had passed the plateau of youth, who were married and happy and living in Port Washington, Long Island, the commuters' paradise. That's as far as we got in one year. Long conversations until five o'clock in the morning. Back and forth the story went.

Cassavetes'

method was to discover what a film was about in the process of writing,

rehearsing and filming it and to follow those discoveries wherever they

led.

Cassavetes'

method was to discover what a film was about in the process of writing,

rehearsing and filming it and to follow those discoveries wherever they

led.

The characters in Husbands are quite different from those in Faces. I mean Faces was about people who were just getting by. These guys don't want to just get by in life. They want to live. I don't really know what Husbands is about at this point. You could say it's about three married guys who want something for themselves. They don't know what they want, but they get scared when their best friend dies. Or you could say it is about three men that are in search of love and don't know how to attain it. Or you could say it is about a person of sentiment. Every scene in the picture will be our opinions about sentiment. I try to talk to the actors and try to find out what I really think about sentiment. It may turn harsh or bitter; but I can allow anything as long as I know we are honest. We worked with no story, basically no story except what I mentioned, and worked for a year to try to solve it and to gain, to get something out of it.

When you make a film whose interest is to take an extremely difficult subject, deal with it in depth and see if you can find something in yourself, and if other people can find other things within themselves that they will be able to develop in their personal life, it's great. After being an actor for a few years you really don't care about money, fame or glory anymore; those things are good, but you need something more.

Cassavetes' elusiveness about the subject of his film was neither modesty nor coyness. He believed that to lock himself into a predetermined story or a preconceived conception of his characters' identities was too limiting. To play a "character" in a "narrative" was to reduce the sliding, shifting complexity of life to cartoon clichés.

Each moment was found as we went along – not off the cuff, not without reason – but without a preconceived notion that forbids people from behaving like people and tells a "story" that is predictable – and untrue. I hate knowing my theme and my story before I really start. I like to discover it as I work. In Husbands the off-the-set relationship between Gazzara, Falk and myself determined a lot of the scenes we created as we went along. It was a process of discovering the story and the theme. When you know in advance what the story is going to be, it gets boring really fast. At one point we decided that we weren't even going to shoot in London; Peter broke into laughter and so did I. What a terrific thrill to tell the truth – to not protect some stupid idea that doesn't work. From then on, it didn't matter if it was London, Paris, Hamburg – or Duluth!

I believe that if an actor

creates a character out of his emotions and experiences, he should

do

with that character what he wants. If what he is doing comes out of

that, then it has to be meaningful. If Peter and Ben and I have three

characters,

why should a director come in and impose a fourth will? If the feelings

are true and the relationship is pure, the story will come out of that.

If you don't have a script, you don't have a commitment to just saying

lines. If you don't have a script, then you take the essence of what

you

really feel and say that. You can behave more as yourself than you

would ordinarily with someone else's lines. Most directors make a big

mystery

of their work; they tell you about your character and your responsibility

to the overall thing. Bullshit. With people like Ben and Peter you

don't

give directions. You give freedom and ideas.

I believe that if an actor

creates a character out of his emotions and experiences, he should

do

with that character what he wants. If what he is doing comes out of

that, then it has to be meaningful. If Peter and Ben and I have three

characters,

why should a director come in and impose a fourth will? If the feelings

are true and the relationship is pure, the story will come out of that.

If you don't have a script, you don't have a commitment to just saying

lines. If you don't have a script, then you take the essence of what

you

really feel and say that. You can behave more as yourself than you

would ordinarily with someone else's lines. Most directors make a big

mystery

of their work; they tell you about your character and your responsibility

to the overall thing. Bullshit. With people like Ben and Peter you

don't

give directions. You give freedom and ideas.

Cassavetes and his actors couldn't say where they were going to come out in advance because the actors were on a voyage of exploration. Acting was not about pretending to be something but about discovering what you really were. The feelings in the film were not poses but states of real emotional exposure. You were really to listen, think and react.

An actor can't suddenly deny or reject a part of himself under the pretext of playing a particular character, even if that's what he would like to do. You can't ask someone to forget themselves and become another person. If you were asked to play Napoleon in a picture, for example, you can't really have his emotions and thoughts, only yours. You could never actually be Napoleon, only yourself playing him. I've never wanted to play a role. Honestly, I never have! That indicates to me that you want to step forward and show someone something, and that terrifies me, really. What you want to do is be invisible as that character, so that there's no pressure on you worrying about the outside world.

* * *

Cassavetes was committed

to exploring the truth about these men and their feelings, wherever it

might lead.

Husbands depicts

the American man without any camouflage. It's very difficult for some

people to feel, or to see themselves in a bad form. I think that people

in films are expected to be heroes, even with the anti-hero situation

going on for years and years in literature. People expect too much from

themselves, they want to look great. You know what actors are? They're

"professional people." They get paid for being people. If you

don't have any weaknesses, you'd be a superhero! [I try to have] the actors

try not to be better than they are. The strange thing is that in this

way they reveal themselves as human beings.

The goal was to explore

emotional realities, however ugly, embarrassing, or painful they might

be:

The job that has to be done here is for three men to investigate

themselves – honestly,

without suppression. It's very difficult for someone to reveal themselves.

It's very difficult to say what you really mean, because what you really

mean is painful. I can't help being like most everybody else sometimes,

pushing down what I feel so far that even when I hear my own feelings

described, it sounds alien, foreign, unconnected. The most terrifying

thing for me is to face myself utterly and truthfully. While working

on

[Husbands], I was forced to ask myself questions I never asked

myself before. Ben and Peter had to do the same thing. We had to open

ourselves up and look at ourselves, and we all have hang-ups.

Is it really better to be a man-child or to be a man? I don't know.

The minute

you settle down and say, "That's it. I'm closing shop. I know what

I am," then you're a man, no longer a man-child. And none of us

are really all that open, and we're a little defensive. So the three

of us

would sit down and talk and improvise and give ourselves a problem by

putting ourselves in a real situation and trying to find out the honest

answers. And I'd write the scene, and rewrite, and we'd improvise again.

Every actor – every good actor – does this or tries to

do this with every

part he plays. What we have given to the film as actors has been what

we are. Where we have failed is when we couldn't reach ourselves and

the

essence of what we really feel, or we were too shy or inhibited to let

it out.

The only thing that counts is that you're all doing the same thing, you're testing each other, testing yourself. In that situation each actor is thinking, "How far up can I reach?" That's selfish – and honest. I don't think Peter and Benny were too concerned about how far I could go as a director; they were thinking about how far they could go as actors. And, in a realistic sense, Benny couldn't go any place unless Peter was good and unless I was good. So we knew we had to work on that level, and in order to do that, we had to get tight with each other.

As it did in Faces,

Cassavetes' references to "improvisation" in post-release

interviews created misunderstandings about his working methods.

It is clear that,

for him, improvisation was a way of refining a script – not

of doing without it:

I think you have to define what improvisation does – not what

it is. Improvisation to me means that there is a characteristic spontaneity

in

the work which makes it appear not to have been planned. I write a very

tight script, and from there on in I allow the actors to interpret it

the way they wish. But once they choose their way, then I'm extremely

disciplined – and they must also be extremely disciplined about

their own

interpretations. There's a difference between ad-libbing and improvising,

and there's a difference between not knowing what to do and just saying

something. [I believe in] improvising on the basis of the written work,

and not on undisciplined creativity. When you have an important scene,

you want it written; but there are still times when you want things just

to happen.

Illustrations of how Cassavetes

worked. Here he is planning and directing the scene involving Harry, his

wife, and his mother-in-law:

I realized in making the picture, that it was more difficult dealing

with three guys and what three guys wanted, than it was dealing with one

guy and what he wanted. I was constantly aware of the structural problems.

One of us had a turn, and then another, and then another. Somehow the

picture had to start taking over so that nobody had any more turns. What

is happening evolves out of the action, but there is no specific importance

to individual incidents. This scene with Ben evolved because we knew that

people would say, "Gee, you never saw one wife." That just kept

ringing in my mind. I didn't want people to approach me on the street

and say, "Isn't it wonderful? You never saw a wife in that."

That's kind of a nightmare. We decided to show the one wife. To do that

we had to come up with some kind of relationship that would be meaningful

for the other two guys. We wrote a very quick scene. We got the actors

in, and got a stage. It was all very stagy. I knew that it would pay off

once he choked the mother-in-law.

On the set:

Ben, you'll go into the bathroom and start to shave. Your mother-in-law

comes in. I don't know what I'll do with her, maybe I'll have her sit

on the edge of the tub and watch you. There are three things you have

to keep in mind – one, she's a mother, that's what she is first

of all; two, you like her and she likes you – she's an intelligent

woman and she

knows that what's wrong with the marriage is that you try too hard; three,

she's the enemy and don't you forget it – because if the marriage

breaks

up, she's not going with you.

The

scene with the "Countess"

was inspired by an extra in the casino scene. Cassavetes' comments illustrate

his willingness to do anything necessary to get a good performance – even

to the point of making the actor uncomfortable.

The

scene with the "Countess"

was inspired by an extra in the casino scene. Cassavetes' comments illustrate

his willingness to do anything necessary to get a good performance – even

to the point of making the actor uncomfortable.

You see that woman sitting there and you've got to have her in the

scene. So I took that lady and Peter and I wrote a scene [on the spot]

and gave it to him. The secretary wrote it out and gave it to Peter and

to the lady, and she looked at it. Peter was all right, but how could

she catch up? She was just sitting there. She was out of place. She didn't

know what to expect. All the camera crew and everybody else was looking

at this woman. What was going to happen? She had a few lines, and

she had to, in a sense, be romantic. Sometimes it's utter and total cruelty

to elicit something pretty out of somebody. You have to be cruel to somebody

sometimes, but it is only cruel in some kind of a social bullshit way.

I mean, we're all there to get something good. The woman was tight. She

didn't know what was expected of her, and it was too late for her to find

out in the course of the filming. I would say terrible things to her,

just awful things. She would fight them off like a lady. She reached a

point where she could do everything by herself. She was grateful for that

attitude of not giving a shit of what anybody else thought, because everything

bad had already happened. From there on in, she just started to play.

She was herself, which she had to be. Peter played the scene with her.

It was very good, and she was very good. I would say things like, "Look

at that face."

It's terrific for Peter to try to pick up that woman. It's right that he would pick her up, because she is the safest woman in the place. It was very easy for him to talk to her. Peter was all right, because he was really comfortable. He was more comfortable in that scene than in a lot of other scenes, because it was right. The situation was right. He would go over and talk to that woman. She's a terrific woman.

* * *

I'm a great believer in spontaneity, because I think planning is the most destructive thing in the world. Because it kills the human spirit. So does too much discipline, because then you can't get caught up in the moment, and if you can't get caught up in the moment, life has no magic. Without the magic, we might as well all give up and admit we're going to be dead in a few years. We need magic in our lives to take us away from those realities. The hope is that people stay crazy. It's really no fun to work with sane people, people who have a set way of doing things.

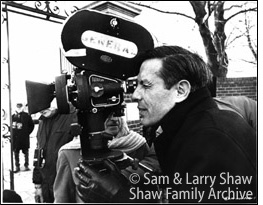

The use of a professional

crew presented a host of problems.

The

most boring thing in the world is to direct a film, set the camera here,

mark the actors, get your focus and light it. The sound should be clear

and the shot should be good – but] professional accuracy seems

to me to have nothing to do with content and since the only people

in the film

that are truly interested in what the film has to say are the actors,

it seemed to me the best choice to make an alliance with them rather

than

the usual alliance with the crew. The director of a film has a tremendous

advantage over the actors and there is no way that he won't use that

advantage.

He is usually the friend of some 50 odd technicians on the floor and

when there is a disagreement between actor and director, the actor

is not arguing

with one man, but with 51. In front of a crew, I'm always in the position

of being in the right and it's easy to blame the actor and to look

hurt.

But then I'm only destroying him, turning him into an enemy, destroying

his dreams and ours too. If I defend myself I'm only destroying myself

and I've never liked directors because this is the attitude they take.

The problem for me, therefore, was the same problem that most actors

face,

they are outnumbered – they are pressed into conformity by the

schedule, by accepted sociability, by heart-warming good mornings and

pleasant

good

nights, platitudes that take up valuable time, being invited to dinner,

cliques of crew that say I like him or I don't like him; insipid arguments

over the content when the scene is good and deathly silence when it's

bad; that feeling that one gets when someone is being shrewd with you

and does not want to offend you enough to lose his next job; that getting-behind-you-for-the-moment

dialogue revolts the person talking and the person listening at once.

It's amazing the hate I can feel to people who pretend they're doing

it and are not, that are lying, and know they are lying. They're the

ones

who insist on behaving in a manner which says: "Please don't reveal

or expose me, because I have to live. I'm a person!" Those are

the ones I always feel like saying to: "Why don't you live someplace

else, because I don't want you around!" I hate people who become

stagnant and just go through life and retreat from any kind of creating

or loving. For them life is a vacuum and even when they get ideas they

are afraid to do anything about it. I don't really feel sorry

for those people. I just hate them. For that reason, the choice of

the crew

becomes extremely important. They have to understand that what they're

doing – no matter how hard they're working – is only

to help what's going

on in front of the camera. Audiences are not watching the technical processes

as hard as they're watching the actors. If the actors are good, the

picture

looks good – I mean, the actual photography looks better when the

actors are better.

The

most boring thing in the world is to direct a film, set the camera here,

mark the actors, get your focus and light it. The sound should be clear

and the shot should be good – but] professional accuracy seems

to me to have nothing to do with content and since the only people

in the film

that are truly interested in what the film has to say are the actors,

it seemed to me the best choice to make an alliance with them rather

than

the usual alliance with the crew. The director of a film has a tremendous

advantage over the actors and there is no way that he won't use that

advantage.

He is usually the friend of some 50 odd technicians on the floor and

when there is a disagreement between actor and director, the actor

is not arguing

with one man, but with 51. In front of a crew, I'm always in the position

of being in the right and it's easy to blame the actor and to look

hurt.

But then I'm only destroying him, turning him into an enemy, destroying

his dreams and ours too. If I defend myself I'm only destroying myself

and I've never liked directors because this is the attitude they take.

The problem for me, therefore, was the same problem that most actors

face,

they are outnumbered – they are pressed into conformity by the

schedule, by accepted sociability, by heart-warming good mornings and

pleasant

good

nights, platitudes that take up valuable time, being invited to dinner,

cliques of crew that say I like him or I don't like him; insipid arguments

over the content when the scene is good and deathly silence when it's

bad; that feeling that one gets when someone is being shrewd with you

and does not want to offend you enough to lose his next job; that getting-behind-you-for-the-moment

dialogue revolts the person talking and the person listening at once.

It's amazing the hate I can feel to people who pretend they're doing

it and are not, that are lying, and know they are lying. They're the

ones

who insist on behaving in a manner which says: "Please don't reveal

or expose me, because I have to live. I'm a person!" Those are

the ones I always feel like saying to: "Why don't you live someplace

else, because I don't want you around!" I hate people who become

stagnant and just go through life and retreat from any kind of creating

or loving. For them life is a vacuum and even when they get ideas they

are afraid to do anything about it. I don't really feel sorry

for those people. I just hate them. For that reason, the choice of

the crew

becomes extremely important. They have to understand that what they're

doing – no matter how hard they're working – is only

to help what's going

on in front of the camera. Audiences are not watching the technical processes

as hard as they're watching the actors. If the actors are good, the

picture

looks good – I mean, the actual photography looks better when the

actors are better.

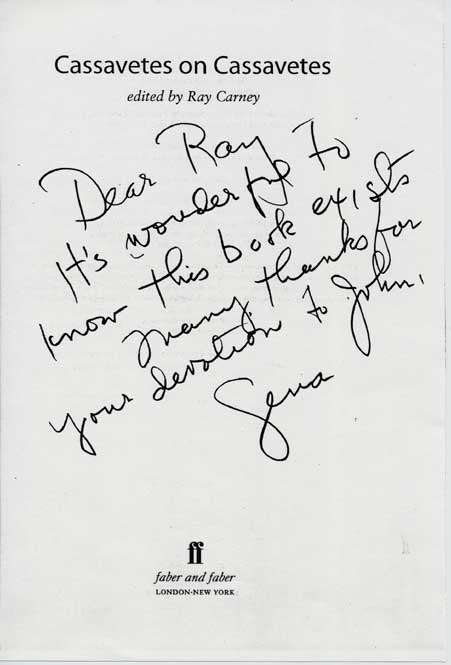

This page only contains excerpts and selected passages from Ray Carney's writing about John Cassavetes. To obtain the complete text as well as the complete texts of many pieces about Cassavetes that are not included on the web site, click here.