Description

Description is one type of writing. Description can help readers imagine what an on-the-spot observer really takes in through the senses. A vivid description will give the reader a vivid experience of being in the presence of the person or thing, or being in the place, that the writer describes.

"Guavas" Esmeralda Santiago

Barco que no anda, no llega a puerto.

A ship that doesn’t sail, never reaches port.

There are guavas at the Shop & Save. I pick one the size of a tennis ball and finger the prickly stem end. It feels familiarly bumpy and firm. The guave is not quite ripe; the skin is still a dark green. I smell it and imagine a pale pink center, the seeds tightly embedded in the flesh.

A ripe guave is yellow, although some varieties have a pink tinge. The skin is thick, firm, and sweet. Its heart is bright pink and almost solid with seeds. The most delicious part of the guava surrounds the tiny seeds. If you don’t know how to eat a guava, the seeds end up in the crevices between your teeth.

When you bite into a ripe guava, your teeth must grip the bumpy surface and sink into the thick edible skin without hitting the center. It takes experience to do this, as it’s quite tricky to determine how far beyond the skin the seeds begin.

Some years, when the rains have been plentiful and the nights cool, you can bite into a guava and not find many seeds. The guava bushes grow close to the ground, their branches laden with green then yellow fruit that seem to ripen overnight. These guavas are large and juicy, almost seedless, their roundness enticing you to have one more, just one more, because next year the rains may not come.

As children, we didn’t always wait for the fruit to ripen. We raided the bushes as soon as the guavas were large enough to bend the branch.

A green guava is sour and hard. You bite into it at its widest point, because it’s easier to grasp with your teeth. You hear the skin, meat, and seeds crunching inside your head, while the inside of your mouth explodes in little spurts of sour.

You grimace, your eyes water, and your cheeks disappear as your lips purse in a tight O. But you have another and then another, enjoying the crunchy sounds, the acid taste, the gritty texture of the unripe center. At night, your mother makes you drink castor oil, which she says tastes better than a green guava. That’s when you know for sure that you’re a child and she has stopped being one.

I had my last guava the day we left Puerto Rico. It was large and juicy, almost red in the center, and so fragrant that I didn’t want to eat it because I would lose the smell. All the way to the airport I scratched at it with my front teeth, making little dents in the skin, chewing small pieces with my front teeth, so that I could feel the texture against my tongue, the tiny pink pellets of sweet.

Today, I stand before a stack of dark green guavas, each perfectly round and hard, each $1.59. The one in my hand is tempting. It smells faintly of late summer afternoons and hopscotch under the mango tree. But this is autumn in New York, and I’m no longer a child.

The guava joins its sisters under the harsh fluorescent lights of the exotic fruit display. I push my cart away, toward the apples and pears of my adulthood, their nearly seedless ripeness predictable and bittersweet.

www.alohafriends.com/ tropical_flowers.html

www.vassallucci.nl/vassa/auteurs/santiago.htm

Are you describing a person? What do you notice first about that person? Maybe it is the person’s eyes. Then go on to what draws your eye next, and next.

Maybe you are writing a purely technical description of something (a chemical reaction, for example) or someone (if you are a medical person describing the feet of someone who has stepped into poison ivy). In these cases you would try to be as "objective" as possible, and keep your opinions and feelings out of your description.

But very often, when we write a description of a place or of a person, we want the reader to feel what we felt when we were in that place, or in the presence of that person. We want to create a dominant impression. We present details that all work toward communicating that dominant impression, and on rereading the description we might add or omit details that will make the dominant impression stronger.

When we look at an image–a photograph or painting, for example–we can often imagine what dominant impression the photographer or painter wanted to communicate.

Edward Hopper,

House by the Railroad(1925)

Oil on canvas, 24 inches x 29 inches. Museum of Modern Art, New York City.

Edward Hopper

and the House by the Railroad (1925)

Edward Hirsch

Out here in the

exact middle of the day,

This strange, gawky house has the expression

Of someone being stared at, someone holding

His breath underwater, hushed and expectant;

This house is

ashamed of itself, ashamed

Of its fantastic mansard rooftop

And its pseudo-Gothic porch, ashamed

of its shoulders and large, awkward hands.

But the man behind

the easel is relentless.

He is as brutal as sunlight, and believes

The house must have done something horrible

To the people who once lived here

Because now it

is so desperately empty,

It must have done something to the sky

Because the sky, too, is utterly vacant

And devoid of meaning. There are no

Trees or shrubs

anywhere--the house

Must have done something against the earth.

All that is present is a single pair of tracks

Straightening into the distance. No trains pass.

Now the stranger

returns to this place daily

Until the house begins to suspect

That the man, too, is desolate, desolate

And even ashamed. Soon the house starts

To stare frankly

at the man. And somehow

The empty white canvas slowly takes on

The expression of someone who is unnerved,

Someone holding his breath underwater.

And then one day

the man simply disappears.

He is a last afternoon shadow moving

Across the tracks, making its way

Through the vast, darkening fields.

This man will

paint other abandoned mansions,

And faded cafeteria windows, and poorly lettered

Storefronts on the edges of small towns.

Always they will have this same expression,

The utterly naked

look of someone

Being stared at, someone American and gawky.

Someone who is about to be left alone

Again, and can no longer stand it.

http://www.emory.edu/ENGLISH/classes/paintings&poems/house.html

Sometimes, however, it is hard to figure out how a photographer or a painter or a sculptor wants us to feel about the subject. And sometimes we don’t even know if the artist wants us to feel any particular way or is just leaving it up to us.

www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/estes_richard.html

www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/estes_richard.html

www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/estes_richard.html

Does the following description create a dominant impression?

Judith Ortiz Cofer wrote the following description of a school that she attended in the U.S. after she arrived here from her homeland of Puerto Rico. Do you think her description shows how she felt about the building, or is it a purely objective description that doesn’t create a dominant impression?

The school building was not a welcoming sight for someone used to the bright colors and airiness of tropical architecture. The building looked functional. It could have been a prison, an asylum, or just what it was: an urban school for the children of immigrants, built to withstand waves of change, generation by generation. Its red brick sides rose to four solid stories. The black steel fire escapes snaked up its back like exposed vertebrae. A chain link fence surrounded its concrete playground. Members of the elite safety patrol, older kids, sixth graders mainly, stood at each of its entrances, wearing their fluorescent white belts that criss-crossed their chests and their metal badges. No one was allowed in the building until the bell rang, not even on rainy or bitter-cold days. Only the safety patrol stayed warm.

Judith Ortiz Cofer, Silent Dancing: A Partial Remembrance of a Puerto Rican Childhood (in Kirszner and Mandell, 59+.)

Is the following description of a place clearly organized?

In order to help the reader, the writer needs to present the descriptive details in an orderly way. Have you ever used a computer program that takes you on a virtual tour of a house? The camera acts as your eyes, walking you toward, into and around the place. Your written description of a place should be done in a similar way; pretend that you are actually walking and your description will be in spatial order and easy for the reader to follow.

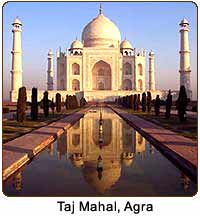

Have you ever visited the Taj Mahal? From reading the description, can you label the diagram on the handout?

www.allindiatravels.com/golden-triangle.html

The Taj Mahal

Shah Jahan, a Moghul emperor, completed the Taj Mahal in 1648 as a memorial to his wife, Mumtaz Mahal. He called the domed memorial the "taj" after the Persian word for a tall, cone-shaped hat; the word "Mahal" was his wife's name. It took hundreds of workmen 18 years to complete this beautiful domed structure. Shah Jahan meant the Taj Mahal to be both a memorial to his queen and a place of Moslem pilgrimage. He also meant it to be a burial place for both himself and his wife.

The Taj Mahal stands on the bank of the Jumna River at Agra in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh. It is open daily from sunrise to sunset. For two rupees, or 12 cents (U.S.), anyone can enter this place of harmony and beauty.

As you enter, you pass through quiet gardens. From the gardens, you cross a broad courtyard. Suddenly, you see the tomb through a tall, arched gateway in the distance. From the cool, dark interior of this gate, the Taj Mahal seems to float between earth and sky. At daybreak, its white marble walls glow rose. At noon, they blaze white. At dusk, they become dark gray. The Taj Mahal is most beautiful by the light of the full moon. Ah, then a visitor can feel a strong sense of romance and mystery!

Beyond the gate, you step onto a broad platform overlooking another garden. At this point, everything before you directs your eye to the Taj Mahal itself. Two shallow pools mirror its great dome. Beds of brilliant flowers, parallel rows of trees, and four minarets frame the great structure. It is almost impossible not to start down the stone steps toward the tomb, where the lovers rest side by side in adjacent graves.

Hundreds of years after its completion, the Taj Mahal remains what the inscription on the entrance gate says--" a palace of pearls where the pious can live forever."

Blanton, Linda Lonon. Composition Practice, Book 3, 2nd ed. Boston: Henle&Heinle, 1993p.5, 8.

Assignment: Think of a beautiful place that you have visited and describe it in the spatial way that the Taj Mahal is described above. That is, describe what you see as you approach the place, and then what you see, hear, smell, and feel as you walk into the place and through it. In other words, take your reader on a guided tour of the place. You might choose to describe a temple, a palace, a park, or a place in the mountains. In addition to your written description, draw a diagram of the place, indicating the path that you are leading us along.