|

Week of 27 February 1998 |

Vol. I, No. 22 |

Feature Article

Engineering prof is a prize-winning cricketer

by Cliff Bernard

The sun may have set on the British Empire but in a little corner of Massachusetts its legacy lives on. There you can hear the thwack of leather on willow and the cry familiar to all inhabitants of the British Commonwealth of Nations: "How-zat!" (This shout means that the fielder is challenging the umpire.) If the Melbourne Cricket Club (see sidebar) is at bat, you may see ENG Associate Professor of Manufacturing Engineering Soumendra Basu tapping his bat on the pitch in the opening over, prepared for an off-spin, a bumper, a googly, or whatever the bowler might throw at him.

Cricket is a little like baseball. In both games, players try to hit balls with bats and make runs. One team's turn at bat in cricket is called an innings. The batting team tries to score runs while the bowling team tries to put the batting players out. When one side is all out, the other side bats and tries to beat the first team's score. Both games are slow by basketball standards, and both are a kind of meditation, a study in nerves and tactics rather than a display of athletic prowess.

|

|

|

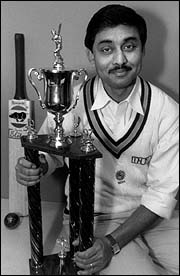

ENG's Soumendra Basu

Photo by Kalman Zabarsky

|

"Sometimes I work out a few things with the students," he explains. Basu cultivates a neatly trimmed mustache and has dark, wavy hair. He is patient and earnest as he discusses his work. "Here we were working out how alloys at high temperature form protective coatings."

But if engineering is his vocation, then cricket is his passion. Does engineering help him as he watches a tiny red ball hurtling towards him? Does he calculate trajectory, speed, and deceleration?

"Well, of course, that's the stereotype of the engineer, isn't it?" Basu smiles. "But when I am looking at a ball coming towards me at 80 miles an hour, I rely on instinct, not analysis."

|

The Melbourne Cricket Club, named after the famous MCC in Melbourne, Australia, is based in Dorchester and heads a league of 16 teams, made up mostly of West Indian immigrants from Dorchester, Roxbury, and Roslindale. They play on eight fields around the Boston area, all of which are dedicated cricket pitches. The season starts in May and runs until late August, and there are 25 games per season, usually attracting an audience of about 100 spectators. Teams and spectators are mostly West Indians, with a few Britons and Australians. |

According to Basu, Indian children grow up with cricket, playing it in vacant lots much as American children play baseball or stickball, making a cricket pitch out of any patch of unused ground they can find. "I started playing cricket at three," he says. "All the children in Delhi do. They know all the great players."

So it was natural that when Basu came to Boston to work on his Ph.D. at MIT, he should take up cricket again with the MIT cricket team. MIT was affiliated with the Massachusetts Cricket League, and was one of six leagues in the United States Cricket Federation. As team members graduated, they kept up the team, renaming it the Melbourne Cricket Club, after its prestigious namesake in Melbourne, Australia.

The Massachusetts Cricket League, founded by West Indian immigrants, has 16 teams and plays, Basu says, at a very high level. "Though the standard is not so high as it was. Some of the players are getting older you know." Basu himself, deep into his thirties, concedes that his own game has slowed a little. "In the field, I used to play slips, but now I play cover/gully." This is analogous to a baseball player moving from the infield to the outfield.

Nevertheless, Basu's play is good enough to have earned him the Most Valuable Player trophy from the Melbourne Cricket Club last October, an event heralded by the Boston Globe. The trophy was presented by one of Basu's idols, cricketing great Sir Gary Sobers.

While Basu has given a lot of his life to cricket, cricket has, he points out, given a lot back, even helping him with his career. Entrance requirements to Indian universities are stringent, and candidates are required not only to excel in academics, but in another interest or skill, such as a sport or hobby. For Basu it was cricket, and he says that his interest helped him get into the Indian Institute of Technology in New Delhi, where he specialized in mechanical engineering. From there he earned an M.S. in materials science from Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland and a Ph.D. in high-temperature oxidation behavior from MIT. Now he passes on his engineering skills and knowledge to his BU students. His cricketing skills he hopes to pass on to his son.